Odawa

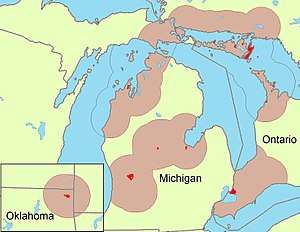

The Odawa[1] (also Ottawa or Odaawaa /oʊˈdɑːwə/), said to mean "traders", are an Indigenous American ethnic group who primarily inhabit land in the Eastern Woodlands region, commonly known as the northern United States and southern Canada. They have long had territory that crosses the current border between the two countries, and they are federally recognized as Native American tribes in the United States and have numerous recognized First Nations bands in Canada. They are one of the Anishinaabeg, related to but distinct from the Ojibwe and Potawatomi peoples.[2]

Odawa group areas. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 15,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Oklahoma, Michigan) Canada (Ontario) | |

| Languages | |

| English, French, Ojibwe (Ottawa dialect) | |

| Religion | |

| Midewiwin, Animism, traditional religion, Christianity, other | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and other Algonquian peoples |

After migrating from the East Coast in ancient times, they settled on Manitoulin Island, near the northern shores of Lake Huron, and the Bruce Peninsula in the present-day province of Ontario, Canada. They considered this their original homeland. After the 17th century, they also settled along the Ottawa River, and in the states of Michigan and Wisconsin, as well as through the Midwest south of the Great Lakes in the latter country.[3] In the 21st century, there are approximately 15,000 Odawa living in Ontario, and Michigan and Oklahoma (former Indian Territory, United States).

The Ottawa dialect is part of the Algonquian language family. This large family has numerous smaller tribal groups or "bands," commonly called "Tribe" in the United States and "First Nation" in Canada. Their language is considered a divergent dialect of Ojibwe, characterized by frequent syncope.[4]

Tribe name

Odawaa (syncoped as Daawaa, is believed to be derived from the Anishinaabe word adaawe, meaning "to trade," or "to buy and sell"); this term is common to the Cree, Algonquin, Nipissing, Montagnais, Odawa, and Ojibwe. The Potawatomi spelling of Odawa and the English derivative "Ottawa" are also common. The Anishinaabe word for "Those men who trade, or buy and sell" is Wadaawewinini(wag). Fr. Frederic Baraga, a Catholic missionary in Michigan, transliterated this and recorded it in his A Dictionary of the Otchipwe Language as "Watawawininiwok," noting that it meant "men of the bulrushes", associated with the many bulrushes in the Ottawa River.[5] But, this recorded meaning is more appropriately associated with the Matàwackariniwak, a historical Algonquin band who lived along the Ottawa River. The only American tribe that is Odawa are the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians, the rest are considered Ottawa.

Their neighbors applied the "Trader" name to the Odawa because in early traditional times, and also during the early European contact period, they were noted as intertribal traders and barterers.[6] The Odawa were described as having dealt "chiefly in cornmeal, sunflower oil, furs and skins, rugs and mats, tobacco, and medicinal roots and herbs."[7][8]

The Odawa name in its English transcription is the source of the place names of Ottawa, Ontario, and the Ottawa River. The Odawa home territory at the time of early European contact, but not their trading zone, was well to the west of the city and river named after them. Ottawa, Ohio is the county seat of Putnam County, developed at the site of the last Ottawa reservation in Ohio.

Language

The Odawa dialect is considered one of several divergent dialects of the Ojibwe language group, noted for its frequent syncope. In the Odawa language, the general language group is known as Nishnabemwin, while the Odawa language is called Daawaamwin. Of the estimated 5,000 ethnic Odawa and additional 10,000 people with some Odawa ancestry, in the early 21st century an estimated 500 people in Ontario and Michigan speak this language. The Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma has three fluent speakers.[9]

Early history

Oral histories and early recorded histories

According to Anishinaabeg tradition, and from recordings in Wiigwaasabak (birch bark scrolls), the Odawa people came from the eastern areas of North America, or Turtle Island, and from along the East Coast (where there are numerous Algonquian-language peoples). Directed by the miigis (luminescent) beings, the Anishinaabe peoples moved inland along the Saint Lawrence River. At the "Third Stopping Place" near what is now Detroit, Michigan, the southern group of Anishinaabeg divided into three groups, the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi.[10]

There is archaeological evidence that the Saugeen Complex people, a Hopewell-influenced group who were located on the Bruce Peninsula during the Middle Woodland period, may have evolved into the Odawa people. The Hopewell tradition was a widely extended trading network operating from about 200BCE to 500 CE. Some of these peoples constructed earthwork mounds for burials, a practice that ended about 250 CE.[11] The Saugeen mounds have not been excavated.

The Odawa, together with the Ojibwe and Potawatomi, were part of a long-term tribal alliance called the Council of Three Fires,[12] which fought the Iroquois Confederacy and the Dakota people. In 1615 French explorer Samuel de Champlain met 300 men of a nation which, he said, "we call les cheueux releuez" (modern French: cheveux relevez (hair lifted, raised, rolled up)) near the French River mouth. Of these, he said: "Their arms consisted only of a bow and arrows, a buckler of boiled leather and the club. They wore no breech clouts, their bodies were tattooed in many fashions and designs, their faces painted and their noses pierced."[7] In 1616, Champlain left the Huron villages and visited the "Cheueux releuez," who lived westward from the lands of the Huron Confederacy.[10]

The Jesuit Relations of 1667 report three tribes living in the same town: the Odawa, the Kiskakon Odawa, and the Sinago Odawa. All three tribes spoke the same language.[13]

Fur trade

Due to the extensive trade network maintained by the Odawa, many of the North American interior nations became known by names which their trading partners used for them, rather than by the nations’ own names (antonyms). For example, these exonyms include Winnebago (from Wiinibiigoo) for the Ho-Chunk, and Sioux (from Naadawensiw) for the Dakota. From the start of the colony of New France, the Odawa became so important to the French and Canadians in fur trade that before 1670, colonists in Quebec (then called Canada) usually referred to any Algonquian speaker from the Great Lakes region as an Odawa. In their own language, the Odawa (like the Ojibwe) identified as Anishinaabe (Neshnabek) meaning "people."

The mostly highly prized fur was beaver. Other furs traded included deer, marten, raccoon, fox, otter, and muskrat. In exchange the Odawa received "hatchets, knives, kettles, traps, needles, fish hooks, cloth and blankets, jewelry and decorative items, and later firearms and alcohol."[14] Up to the time of Nicolas Perrot the Odawa had a monopoly on all fur trade that came through Green Bay, Wisconsin or Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. They allegedly did "their best to exploit" the tribes in those areas "who did not use the canoe, by bartering with them bits of iron and steel and worn-out European articles for extravagant quantities of furs." For example, "the Crees gave the Ottawas 'all their beaver robes for old knives, blunted awls, wretched nets and kettles used until they were past service.'"[15]

Wars and refugees

.jpg)

The Odawa had disputes and warfare with other tribes, particularly over the lucrative fur trade. For example, the tribe once waged war against the Mascouten. In the mid-17th century the Odawa allied with other Algonquian tribes around the Great Lakes against the powerful Mohawk (of present-day New York) and their Iroquois allies in the Beaver Wars. The traditional balance of power in the region had been destroyed by the European introduction of guns and other weapons, changing economic risks and rewards. This disruption produced novel disastrous unintended consequences. All indigenous peoples on both sides were disrupted or decimated; some groups, such as the Iroquoian Erie, were exterminated as tribes. By the mid-17th century, the tribes were more severely affected by disease than warfare. Lacking acquired immunity to the new European infectious diseases, they suffered epidemics with high fatalities.

In 1701 the French colonists built Fort Detroit and established a trading post. Many Odawa moved there from their traditional homeland of Manitoulin Island near the Bruce Peninsula,[10] and Wyandot (Huron) also moved near the post. Some Odawa had already settled across northern Michigan in the Lower Peninsula, and more bands established villages around and south of Detroit. Their area extended into present-day Ohio.

With movements of the tribes in relation to warfare and colonial encroachment, the tribes settled in roughly the following pattern: "Sandwiched between the French, in the north and west, and the English, in the south and east, the Miami settled in present-day Indiana and western Ohio; the Ottawa settled in Northwest Ohio along the Maumee, the Auglaize, and the Blanchard rivers; the Wyandot settled in Central Ohio; the Shawnee in Southwest Ohio; and the Delaware (Lenape) in Southeast and Eastern Ohio."[16]

In the mid-18th century, the Odawa allied with their French trading partners against the British in the Seven Years' War, known as the French and Indian War in the North American colonies. They made raids against Anglo-American colonists. The noted Odawa chief Pontiac[17] has historically been reported to have been born at the confluence of the Maumee and Auglaize rivers, where modern Defiance, Ohio later developed. In 1763, after the British had defeated France, Pontiac led a rebellion against the British, but he was unable to prevent British colonial settlement of the region.[18]

A decade later, Chief Egushawa (also spelled Agushawa), who had a village at the mouth of the Maumee River on Lake Erie where Toledo later developed, led the Odawa as an ally of the British in the American Revolutionary War. He hoped to build on their support to exclude the European-American colonists from his territory in northwest Ohio and southern Michigan.[19] The defeat of the British by the United States had a far-ranging influence on British-allied Native American/First Nations tribes, as many were forced to cede their land to the United States.

Following the Revolutionary War, in the 1790s, Egushawa, together with numerous members of other regional tribes, including the Wyandot and Council of Three Fires, Shawnee, Lenape, and Mingo, fought the United States in a series of battles and campaigns in what became known as the Northwest Indian War. The Indians hoped to repulse the European-American pioneers coming to settle west of the Appalachian Mountains, but were finally defeated.[19] In a campaign during 1794, Anthony Wayne built a string of forts in the upper Maumee River watershed, including Fort Defiance, across the river from the site of Pontiac's birth. While the British had encouraged this effort, they did not want to get drawn into open conflict again with the United States and withdrew from offering direct support to the Native Americans. Wayne's army defeated several hundred members of the Indian confederacy at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, near the future site of Maumee, Ohio and about 11 miles upriver of present-day Toledo.

Raid on Pickawillany

In the winter of 1751–1752, Charles Langlade began assembling a war party of Odawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibwe warriors who traveled to Pickawillany. They attacked the village in mid-morning on June 21, 1752, and killed thirteen Miami men and captured five English traders. Down to as few as twenty warriors the Miami tried to negotiate terms of surrender, and Langlade promised to allow the Miami men to return home if they handed over the English. The Miami only sent three of the five Englishmen. When the Englishmen reached Langlade's lines one of his men stabbed one of the Englishmen to death, scalped him and ripped his heart out and ate it in front of the Miami men. Langlade's men then seized the Miami chief Memeskia, and he was killed, boiled and eaten in front of his Miami men. Afterward the Odawa released the Miami women and left for Detroit with four captured Englishmen and more than $300,000 worth (in today's dollars) of trade goods. This victory over the English led to the French and Indian War and contributed to the Seven Years' War.[20]

Treaties and removals

In 1795, under the Treaty of Greenville, the Odawa and other members of the Western Confederacy ceded all of Ohio except the northwest area. This was part of the area controlled by the Detroit Odawa.

In 1807, the Detroit Odawa joined three other tribes, the Ojibwe, Potawatomi and Wyandot people, in signing the Treaty of Detroit under pressure from the United States. The agreement, between the tribes and William Hull, representing the Michigan Territory, gave the United States a large portion of today's Southeastern Michigan and a section of northwest Ohio near the Maumee River. Many Odawa bands moved into northern Michigan. The tribes retained communal control of relatively small pockets of land in the territory of the Maumee River.[21] Bands of Odawa occupied areas known as Roche de Boeuf,[22] and Wolf Rapids on the upper Maumee River.[23]

In 1817, in the first treaty involving land cessions after the War of 1812, the Ohio Odawa ceded their lands, accepting reservations at Blanchard's Creek and the Little Auglaize River (34 square miles total). These were only reserves, for which they were paid annuities for ten years. Pressure continued to build against the Odawa as European-American settlers moved into the area.

After passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the US government arranged for the Odawa to cede their reserves in 1831. The four following bands eventually all removed to areas of Kansas: Blanchard's Creek, Little Auglaize, Roche de Boeuf, and Wolf Rapids bands.[23]

Modern history

The population of the different Odawa groups has been estimated. In 1906, the Ojibwe and Odawa on Manitoulin and Cockburn Island were 1,497, of whom about half were Odawa. There were 197 Odawa listed as associated with the Seneca School in Oklahoma, where some Odawa had settled after the American Civil War. In 1900 in Michigan there were 5,587 scattered Ojibwe and Odawa, of whom about two-thirds are Odawa.[10]

In the early 21st century, the total number of enrolled members of the federally recognized Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma numbers about 4,700. There are about 10,000 Odawa in the United States, with the majority in Michigan. Another several thousand live in Ontario, Canada.

Known villages

The following are or were Odawa villages:

Former villages not on reserves/reservations

- Aegakotcheising

- Agushawas' Village

- Anamiewatigong

- Apontigoumy

- Machonee

- Menawzhetaunaung

- Michilimackinac

- Ogontz's Village

- Saint Simon Mission

- Shabawywyagun

- Wequetong

Former reserves/reservations and their villages

By the end of the eighteenth century, the Ottawa in Ohio were concentrated in the northwest area along the Maumee River (which has its mouth at Lake Erie.) The reservations and reserves below resulted from the Treaty of Greenville (1795), and following ones. These are listed by Frederick Webb Hodge in his 1910 history of American Indians North of Mexico.[24] Also see Lee Sultzman, "Ottawa History"[23]

- Auglaize Reserve, Ohio – Oquanoxa's Village

- Blanchard's Fork Reserve, Ohio – Lower Tawa Town, Upper Tawa Town

- North Maumee River Reserve, Ohio – Meshkemau's Village, Wassonquet's Village, Waugau's Village

- Obidgewong Reserve, Ontario – Obijewong, Ontario (located 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) east of Evansville, Ontario)

- Roche de Bœuf Reserve, Ohio – Nawash's Village, Tontaganie's Village

- South Maumee River Reserve, Ohio – 34-mile square reserve on the south side of the river. McCarty's Village ("Tushquegan") was the principal one, located near Presque Isle. Ottokee and his band lived at the mouth of the Maumee River; he was a son of Otussa and grandson of chief Pontiac. His group were the last of the Odawa to remove from Ohio to Kansas in 1839.[25]

- Wolf Rapids Reserve, Ohio – Kinjoino's Village ("Anpatonajowin" (Aabitanagaajiwan))

- Ottawas of Blanchard's Fork Indian Reservation, Kansas – Ottawa

- Ottawas of Roche de Bœuf and Wolf Rapids Indian Reservation, Kansas

Current reserves/reservations and associated villages

- Grand Traverse Indian Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, Michigan – Peshawbestown

- Little River Indian Reservation, Michigan – Manistee, Muskegon

- Little Traverse Bay Indian Reservation, Michigan ("Wequetonsing" (Wiikwedoonsing)) – Charlevoix, Cross Village, Harbor Springs/L'Arbre Croche ("Waganakisi" (Waaganaakizi)), Middle Village, Petoskey

- M'Chigeeng 22 Indian Reserve, Ontario – M'Chigeeng (formerly known as "West Bay")

- Ottawa OTSA, Oklahoma – Miami, Oklahoma

- Point Grondine Indian Reserve, Ontario – Beaverstone

- Sheshegwaning 20 Indian Reserve, Ontario – Sheshegwaning

- Walpole Island 46 Indian Reserve, Ontario (Bakejiwanong [Bkejwanong]) – Foreplex, Myersville, Wallaceburg, Walpole Island, Williamsville

- Wiikwemkoong Unceded Reserve, Ontario – Buzwah, Kaboni, Maiangowi, Murray Hill, South Bay, Two O'Clock, Wabozominissing, Wikwemikong, Wikwemikonsing

- Zhiibaahaasing 19 Indian Reserve, Ontario (formerly known as "Cockburn Island 19 Indian Reserve")

- Zhiibaahaasing 19A Indian Reserve, Ontario – Zhiibaahaasing

Governments

Recognized/status Odawa governments

United States:

- Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, Michigan[26] (formerly Northern Michigan Ottawa Association, Unit 2)

- Little River Band of Ottawa Indians, Michigan (formerly Northern Michigan Ottawa Association, Unit 7)

- Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, Michigan (formerly Northern Michigan Ottawa Association, Unit 1)

- Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma

Canada:

- M'Chigeeng First Nation (formerly "West Bay First Nation")

- Sheshegwaning First Nation, Ontario[27]

- Walpole Island First Nation, on unceded territory of Walpole Island located between Ontario and Michigan

- Wiikwemkoong First Nation, located on the Wiikwemkoong Unceded Reserve, Ontario

- Zhiibaahaasing First Nation, Ontario (formerly "Cockburn Island First Nation")

Other recognized/status governments with significant Odawa populations

Canada:

- Aamjiwnaang First Nation (Sarnia), Ontario

- Aundeck-Omni-Kaning First Nation (Sucker Creek), Ontario

- Chippewas of Kettle & Stony Point, Ontario

- Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation, Ontario (formerly "Cape Croker First Nation")

- Chippewas of the Thames (Caradoc), Ontario

- Garden River First Nation, Ontario

- Mattagami First Nation, Ontario

- Mississauga First Nation, Ontario

- Saugeen First Nation, Ontario

- Serpent River First Nation, Ontario

- Sheguiandah First Nation, Ontario

- Thessalon First Nation, Ontario

- Whitefish Lake First Nation, Ontario

- Whitefish River First Nation, Ontario

United States:

- Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians of Michigan (formerly Gun Lake Band of Grand River Ottawa Indians and as part of Northern Michigan Ottawa Association, Units 3 and 4)

- Saginaw Chippewa Tribal Nation, Michigan

Unrecognized/non-status Odawa governments

- Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, Michigan (formerly "Northern Michigan Ottawa Association, Unit 8", currently recognized by Michigan)

- Genesee Valley Indian Association (formerly Northern Michigan Ottawa Association, Unit 9)

- Grand River Bands of Ottawa Indians, Michigan (formerly Northern Michigan Ottawa Association, Unit 3, currently recognized by Michigan)

- Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians, Michigan[28] (formerly "Northern Michigan Ottawa Association, Units 11 through 17", currently recognized by Michigan)

- Maple River Band of Ottawa, Michigan

- Muskegon River Band of Ottawa Indians, Michigan (formerly "Northern Michigan Ottawa Association, Unit 5")

- Ottawa Colony Band of Grand River Ottawa Indians, Michigan (currently recognized only as part of the Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians of Michigan) (formerly part of Northern Michigan Ottawa Association, Unit 3)

Notable Odawa people

- Jean-Baptiste Assiginack, chief and public servant

- Andrew Blackbird (ca. 1814/7–1908), tribal leader, historian, and author of tribal histories

- Kelly Church, black ash basket weaver and birch bark biter

- Cobmoosa (1768–1866), chief

- Egushawa (ca. 1726–1796), war chief

- Enmegahbowh (ca. 1807–1902), first Native American to be ordained as an Episcopal priest

- Magdelaine Laframboise, Odawa-French fur trader and businesswoman, also supported public education for children on Mackinac Island; added in 1984 to Michigan's Women's Hall of Fame

- Ningweegon (aka Negwagon), chief of the Odawa of the Michilimackinac region of Michigan, sometimes known in English as "The Wing," or "Wing".

- Daphne Odjig (b. 1919), Woodlands style painter and member of the Indian Group of Seven

- Petosegay (1787–1885), merchant and fur trader

- Pontiac (ca. 1720–1769), chief. Leader of Pontiac's War against British and Americans

See also

- United States Constitution, influence of Native Americans

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 5, 2019. Retrieved March 9, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Odawa at The Canadian Encyclopedia, accessed September 4, 2019

- "First Nations Culture Areas Index". Canadian Museum of Civilization.

- "Odawa", Canadian Oxford Dictionary

- Baraga, Frederick. (1878). A Dictionary of the Otchipwe Language, I, 300.

- Beck, David (2002). Siege and Survival: History of the Menominee Indians, 1634–1856, p. 27. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1330-1.

- Burton, Clarence M. (ed.) (1922). The City of Detroit, Michigan, 1701–1922, p. 49. The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company.

- Wurm, Stephen A., et al. (eds.) (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas, p. 1118. Walter de Gruyter & Co. ISBN 3-11-013417-9.

- Anderton, Alice, PhD. Status of Indian Languages in Oklahoma. Archived September 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Intertribal Wordpath Society. 2009 (16 Feb 2009).

- Frederick Webb Hodge, "Ottawa", Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. N-Z, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1910, pp. 167–172

- "The Archaeology of Ontario-The Middle Woodland Period". Ontario Archaeology. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- Williamson, Pamela, and Roberts, John (2nd ed. 2004). First Nations Peoples, p. 102. Toronto: Emond Montgomery Publications. ISBN 1-55239-144-2.

- Bélanger, Claude. "Quebec History". faculty.marianopolis.edu.

- The Wisconsin Cartographers' Guild (1998). Wisconsin's Past and Present: A Historical Atlas. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. p. 4.

- Brebner, John Bartlet (1966). The Explorers of North America: 1492–1806. Cleveland, OH: The World Publishing Company. p. 188.

- Helen Hornbeck Tanner, ed., Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History (University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1986) pp. 3, 58–59; and R. Douglas Hurt, The Ohio Frontier: Crucible of the Old Northwest, 1720–1830 (Indiana University Press: Bloomington, 1998), pp. 8–12.

- "Biography – PONTIAC – Volume III (1741-1770) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca.

- Vogel, Virgil J. (1986). Indian Names in Michigan, pp. 46–47. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-06365-0.

- Barnes, Celia (2003). Native American Power in the United States, 1783–1795, p. 203. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0-8386-3958-5.

- Treuer, David (2019). The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee. New York: Riverhead Books. p. 50. ISBN 9781594633157.

- "Treaty Between the Ottawa, Chippewa, Wyandot, and Potawatomi Indians". World Digital Library. November 17, 1807. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- "Waterville, Ohio: Roche de Bout Metropark". Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- Lee Sultzman, "Ottawa History", website

- Hodge, Frederick Webb (April 10, 1910). "Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico: N-Z". U.S. Government Printing Office – via Google Books.

- Janet E. Rozick, "Side Cut, Farnsworth, Bend View, and Providence Metroparks", pp. 10–11 (Cited to Tanner, 48 – 51), Larry Angelo, The Migration of the Ottawas from 1615 to Present, (1997), pp. 3–6

- Archived July 9, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- "Domain Default page". Sheshegwaning.org. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- "mackinacbands.com". mackinacbands.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

Further reading

- Cappel, Constance, Odawa Language and Legends: Andrew J. Blackbird and Raymond Kiogima, Xlibris, 2006. (self-published)

- Cappel, Constance, The Smallpox Genocide of the Odawa Tribe at L'Arbre Croche, 1763: The History of a Native American People, Edwin Mellen Press, 2007. (described by academic journal as a vanity press)

- McClurken, James A. Our People, Our Journey: The Little River Band of Ottawa Indians. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2009. This work was a 2010 Michigan Notable Book selected by the Library of Michigan. ISBN 978-0-87013-855-3

- McDonnell, Michael A. Masters of Empire: Great Lakes Indians and the Making of America. New York Hill and Wang, 2015. Maps. 416 pp. ISBN 978-0-8090-2953-2.

- Wolff, Gerald W., and Cash, Joseph H. The Ottawa People, Phoenix, Arizona: Indian Tribal Series, 1976.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Odawa. |

- "Ottawa History" Shultzman, L. (2000). First Nations Histories.

- Frederick Webb Hodge, "Ottawa", Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. N-Z, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1910, pp. 167–172, full text online

- "The Middle Woodland Period", The Archaeology of Ontario

- Odawa at The Canadian Encyclopedia

- Odawa – First Nations seeker

- Odawa – Word finder

Official Tribal Websites

- Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians

- Little River Band of Ottawa Indians

- Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians

- Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma