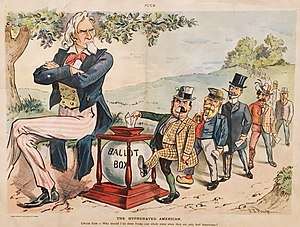

Hyphenated American

In the United States, the term hyphenated American refers to the use of a hyphen (in some styles of writing) between the name of an ethnicity and the word "American" in compound nouns, e.g., as in "Irish-American". It was an epithet used from 1890 to 1920 to disparage Americans who were of foreign birth or origin, and who displayed an allegiance to a foreign country through the use of the hyphen. It was most commonly directed at German Americans or Irish Americans (Catholics) who called for U.S. neutrality in World War I.[1]

In this context, the term "the hyphen" was a metonymical reference to this kind of ethnicity descriptor, and "dropping the hyphen" referred to full integration into the American identity.[2]

President Theodore Roosevelt was an outspoken anti-hyphenate and Woodrow Wilson followed suit.[3] Contemporary studies and debates refer to hyphenated-American identities to discuss issues such as multiculturalism and immigration in the U.S. political climate; however, the hyphen is rarely used per the recommendation of modern style guides.

Nativism and hyphenated Americanism, 1890-1920

The term "hyphenated American" was published by 1889,[4] and was common as a derogatory term by 1904. During World War I the issue arose of the primary political loyalty of ethnic groups with close ties to Europe, especially German Americans and also Irish Americans. Former President Theodore Roosevelt in speaking to the largely Irish Catholic Knights of Columbus at Carnegie Hall on Columbus Day 1915, asserted that,[5]

There is no room in this country for hyphenated Americanism. When I refer to hyphenated Americans, I do not refer to naturalized Americans. Some of the very best Americans I have ever known were naturalized Americans, Americans born abroad. But a hyphenated American is not an American at all ... The one absolutely certain way of bringing this nation to ruin, of preventing all possibility of its continuing to be a nation at all, would be to permit it to become a tangle of squabbling nationalities, an intricate knot of German-Americans, Irish-Americans, English-Americans, French-Americans, Scandinavian-Americans or Italian-Americans, each preserving its separate nationality, each at heart feeling more sympathy with Europeans of that nationality, than with the other citizens of the American Republic ... There is no such thing as a hyphenated American who is a good American. The only man who is a good American is the man who is an American and nothing else.

President Woodrow Wilson regarded "hyphenated Americans" with suspicion, saying, "Any man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready."[6][7][8]

Hyphenated American identities

Some groups recommend dropping the hyphen because it implies to some people dual nationalism and inability to be accepted as truly American. The Japanese American Citizens League is supportive of dropping the hyphen because the non-hyphenated form uses their ancestral origin as an adjective for "American."[9]

By contrast, other groups have embraced the hyphen, arguing that the American identity is compatible with alternative identities and that the mixture of identities within the United States strengthens the nation rather than weakens it.

"European American", as opposed to White or Caucasian, has been coined in response to the increasing racial and ethnic diversity of the US, as well as to this diversity moving more into the mainstream of the society in the latter half of the twentieth century. The term distinguishes whites of European ancestry from those of other ancestries. In 1977, it was proposed that the term "European American" replace "white" as a racial label in the US Census, although this was not done. The term "European American" is not in common use in the US among the general public or in the mass media, and the terms "white" or "white American" are commonly used instead.

Usage of the hyphen

Modern style guides, such as AP Stylebook, recommend dropping the hyphen between the two names;[10] some, including the Chicago Manual of Style, recommend dropping the hyphen even for the adjective form.[11] On the other hand, The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage allows compounds with name fragments (bound morphemes), such as Italian-American and Japanese-American, but not "Jewish American" or "French Canadian."[10]

American English

The first term typically indicates a region or culture of origin ancestry paired with "American". Examples:

- Region, continent or race: African American, Asian American, European American, Latino American, Middle-Eastern American, Native American, or American Indian, Pacific Islands American.

- Ethnicity or nationality: Arab American, Armenian American, British American, Chinese American, Colombian American, Danish American, English American, Filipino American, French American, German American, Greek American, Haitian American, Indian American, Irish American, Italian American, Japanese American, Jewish American, Korean American, Mexican American, Norwegian American, Pakistani American, Polish American, Russian American, Scottish American, Swedish American, Ukrainian American, Vietnamese American, and so on.

The hyphen is occasionally but not consistently employed when the compound term is used as an adjective.[12] Academic style guides (including APA, ASA, MLA, and Chicago Manual) do not use a hyphen in these compounds even when they are used as adjectives.[13]

The linguistic construction functionally indicates ancestry, but also may connote a sense that these individuals straddle two worlds—one experience is specific to their unique ethnic identity, while the other is the broader multicultural amalgam that is Americana.

In relation to Latin America

Latin America includes most of the Western Hemisphere south of the United States, including Mexico, Central America, South America and (in some cases) the Caribbean. U.S. nationals with origins in Latin America are often referred to as Hispanic or Latino-Americans, or by their specific country of origin, e.g., Mexican-Americans, Puerto Ricans and Cuban-Americans.

See also

References

- Sarah Churchwell. America’s Original Identity Politics, The New York Review of Books, February 7, 2019

- Mary Anne Trasciatti. Hooking the Hyphen: Woodrow Wilson '5 War Rhetoric and the Italian American Community, p. 107. In: Beasley, Vanessa B. Who Belongs in America?: Presidents, Rhetoric, and Immigration. College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2006.

- John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925 (1955) online text p 198

- Charles William Penrose (July 6, 1889), "Letter from 'Junius'", The Deseret Weekly, Deseret News Co, 39 (2): 53–54

- "Roosevelt Bars the Hyphenated" (PDF). New York Times. October 13, 1915.

- Woodrow Wilson: Final Address in Support of the League of Nations, americanrhetoric.com

- Di Nunzio, Mario R., ed. (2006). Woodrow Wilson: Essential Writings and Speeches of the Scholar-President. NYU Press. p. 412. ISBN 0-8147-1984-8.

- "Explains our Voting Power in the League" (PDF). New York Times. September 27, 1919.

- See Strasheim (1975).

- Merrill Perlman. AP tackles language about race in this year’s style guide, Columbia Journalism Review, April 1, 2019

- Editorial Style Guide, California State University at Los Angeles, archived from the original on 2008-06-26, retrieved 2007-12-13

- Erica S. Olsen (2000), Falcon Style Guide: A Comprehensive Guide for Travel and Outdoor Writers and Editors, Globe Pequot, ISBN 1-58592-005-3

- "Hyphens, En Dashes, Em Dashes." The Chicago Manual Style Online

Further reading

- Bronfenbrenner, Martin (1982). "Hyphenated Americans. Economic Aspects". Law and Contemporary Problems. 45 (2): 9–27. doi:10.2307/1191401. JSTOR 1191401. on economic discrimination

- Higham, John (1955). Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925. pp. 198ff. ISBN 9780813531236.

- Steiner, Edward A. (1916). Confessions of a Hyphenated American. Fleming H. Revell Company.

- Miller, Herbert Adolphus (1916). "Review of Confessions of a Hyphenated American. by Edward A. Steiner". American Journal of Sociology. 22 (2): 269–271. doi:10.1086/212610. JSTOR 2763826.

- Strasheim, Lorraine A. (1975). "'We're All Ethnics': 'Hyphenated' Americans, 'Professional' Ethnics, and Ethnics 'By Attraction'". The Modern Language Journal. 59 (5/6): 240–249. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1975.tb02351.x. JSTOR 324305.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Hyphenated Americans, The National Museum of American History