New Mexican Spanish

New Mexican Spanish (Spanish: español neomexicano, novomexicano) is a variety of Spanish spoken in the United States, primarily in Northern New Mexico and the southern part of the state of Colorado by the Hispanos of New Mexico. Despite a continual influence from the Spanish spoken in Mexico to the south by contact with Mexican migrants who fled to the US from the Mexican Revolution, New Mexico's unique political history and relative geographical and political isolation from the time of the annexation to the US have caused New Mexican Spanish to differ notably from the Spanish spoken in other parts of Hispanic America, with the exception of certain rural areas of southern Colorado, Northern Mexico, and Texas.[1]

| New Mexican Spanish | |

|---|---|

| español neomexicano, novomexicano | |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Latin (Spanish alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

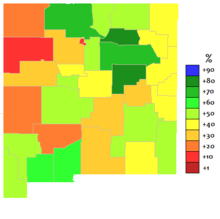

Spanish language distribution in New Mexico by county | |

| Hispanic and Latino Americans |

|---|

|

National origin groups

|

|

Political movements

|

|

Organizations

|

|

Ethnic groups |

|

Lists

|

Many speakers of traditional New Mexican Spanish are descendants of Spanish colonists who arrived in New Mexico in the 16th to the 18th centuries. During that time, contact with the rest of Spanish America was limited because of the Comancheria, and New Mexican Spanish developed closer trading links to the Comanche than to the rest of New Spain. In the meantime, some Spanish colonists co-existed with and intermarried with Puebloan peoples and Navajos, also enemies of the Comanche.[2]

After the Mexican–American War, New Mexico and all its inhabitants came under the governance of the English-speaking United States, and for the next 100 years, English-speakers increased in number.

Those reasons caused these main differences between New Mexican Spanish and other forms of Hispanic American Spanish: the preservation of forms and vocabulary from colonial-era Spanish (such as, in some places, haiga instead of haya or Yo seigo, instead of Yo soy), the borrowing of words from Rio Grande Indian languages for indigenous vocabulary (in addition to the Nahuatl additions that the colonists had brought), a tendency to "recoin" Spanish words for ones that had fallen into disuse (for example, ojo, whose literal meaning is "eye," was repurposed to mean "hot spring" as well), and a large proportion of English loanwords, particularly for technology (such as bos, troca, and telefón). Pronunciation also carries influences from colonial, Native American, and English sources.

In recent years, speakers have developed a modern New Mexican Spanish, called Renovador, which contains more modern vocabulary because of the increasing popularity of Spanish-language broadcast media in the US and intermarriage between New Mexicans and Mexican settlers. The modernized dialect contains Mexican Spanish slang (mexicanismos).[1]

History

The late-19th-century development of a culture of print media allowed New Mexican Spanish to resist assimilation toward either American English or Mexican Spanish for many decades.[3] The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, for instance, noted, "About one-tenth of the Spanish-American and Indian population [of New Mexico] habitually use the English language." Until the 1930s or the 1940s, many speakers never learned English, and even afterward, most of their descendants were bilingual with English until the 1960s or the 1970s. The advance of English-language broadcast media accelerated the decline.

The increasing popularity of Spanish-language broadcast media in the US and intermarriage of Mexican settlers and descendants of colonial Spanish settlers have somewhat increased the number of those speaking New Mexican Spanish.

Morphology

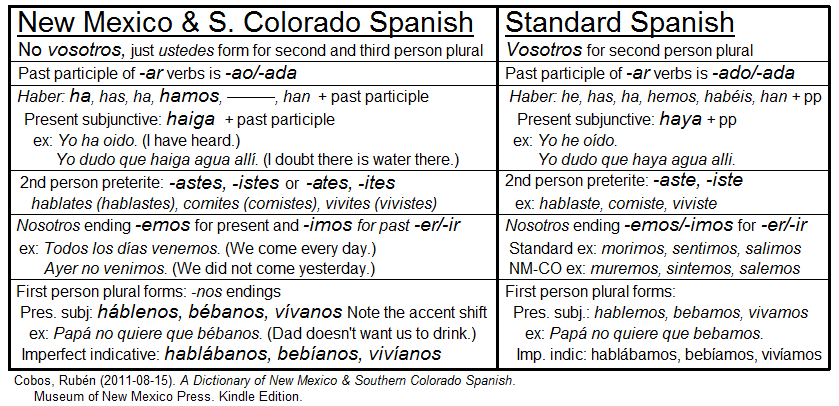

Besides a great deal of phonological variation, there are various morphological differences throughout New Mexican Spanish, usually in the verb conjugations or endings:

- Change from a bilabial nasal /m/ to an alveolar nasal /n/ in the first-person plural (nosotros) ending of the imperfect: nos bañábamos /nos baˈɲabamos/ is pronounced [nos baˈɲa.β̞a.nos] under the influence of clitic nos.

- Regularization of the following irregular verb conjugations:

- Radical stem changes absent: the equivalent of quiero is quero, which is clearly an archaism. In fact, this feature remains in some parts of northwestern Spain such as Asturias and Galicia.

- Regularization of irregular first-person singular (yo) present indicative: epenthetic /g/ is missing, thus salo rather than salgo, veno instead of vengo.

- Subjunctive present of haber is haiga, instead of haya.[1]

- Preservation of /a/ in forms of haber as an auxiliary verb: "nosotros hamos comido," instead of "nosotros hemos comido," "yo ha comido" instead of "yo he comido."[1]

Phonology

- New Mexican Spanish has seseo (orthographic <c> before /e/ and /i/ as well as <z> represent a single phoneme, /s/, normally pronounced [s]). That is, casa ("house") and caza ("hunt") are homophones. Seseo is prevalent in nearly all of Spanish America, in the Canary Islands, and some of southern Spain. where the linguistic feature originates.

There are many variations of New Mexican Spanish (they can be manifest in small or large groups of speakers, but there are exceptions to nearly all of the following tendencies):

| Feature | Example | Phonemic | Standard | N.M. Spanish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phrase-final epenthetical [e] or [i] |

voy a cantar | /ˈboi a kanˈtaɾ/ | [ˈboi̯.a.kanˈtar] | [ˈboi̯.a.kanˈta.ɾe] |

| dame el papel | /ˈdame el paˈpel/ | [ˈda.mel.paˈpel] | [ˈda.mel.paˈpe.li] | |

| Uvularization of /x/ | mujeres | /muˈxeɾes/ | [muˈxe.ɾes] | [muˈχe.ɾes] |

| Conditional elision of intervocalic /ʝ/ | ella | /ˈeʝa/ | [ˈe.ʝa] | [ˈe.a] |

| estrellita | /estɾeˈʝita/ | [es.tɾeˈʝi.ta] | [es.tɾeˈi.ta] | |

| Realization of /ɾ/ or /r/ as an alveolar approximant [ɹ] |

Rodrigo | /roˈdɾiɡo/ | [roðˈɾi.ɣo] | [ɹoðˈɹi.ɣo] |

| "Softening" (deaffrication) of /t͡ʃ/ to [ʃ] [4] | muchachos | /muˈt͡ʃat͡ʃos/ | [muˈt͡ʃa.t͡ʃos] | [muˈʃa.ʃos] |

| Insertion of nasal consonant / nasalisation of vowel preceding postalveolar affricate/fricative |

muchos | /ˈmut͡ʃos/ | [ˈmu.t͡ʃos] | [ˈmun.ʃos] |

| [ˈmũ.ʃos] | ||||

| Elision of word-final intervocalic consonants, especially in -ado[5] |

ocupado | /okuˈpado/ | [o.ku.ˈpa.ðo] | [o.kuˈpa.u] |

| [o.kuˈpa.o] | ||||

| todo | /ˈtodo/ | [ˈto.ðo] | [ˈto.o] | |

| Aspiration or elision (rare) of /f/[6] | me fui | /me ˈfui/ | [me ˈfwi] | [meˈhwi] |

| [meˈwi] | ||||

| No /s/-voicing | estas mismas casas | /ˈestas ˈmismas ˈkasas/ | [ˈes.tazˈmiz.masˈka.sas] | [ˈes.tasˈmis.masˈka.sas] |

| Velarization of prevelar consonant voiced bilabial approximant |

abuelo | /aˈbuelo/ | [a.ˈβ̞we.lo] | [aˈɣʷwe.lo] |

| Syllable-initial, syllable-final, or total aspiration or elision of /s/ |

somos así | /ˈsomos aˈsi/ | [ˈso.mos.aˈsi] | [ˈho.mos.aˈhi] |

| [ˈo.mos.aˈi] | ||||

| [ˈso.moh.aˈsi] | ||||

| [ˈso.mo.aˈsi] | ||||

| [ˈho.moh.aˈhi] | ||||

| [ˈo.mo.aˈi] |

Language contact

New Mexican Spanish has been in contact with several indigenous American languages, most prominently those of the Pueblo and Navajo peoples with whom the Spaniards and Mexicans coexisted in colonial times. For an example of loanword phonological borrowing in Taos, see Taos loanword phonology.

Legal status

New Mexico law grants Spanish a special status. For instance, constitutional amendments must be approved by referendum and must be printed on the ballot in both English and Spanish.[7] Certain legal notices must be published in English and Spanish, and the state maintains a list of newspapers for Spanish publication.[8] Spanish was not used officially in the legislature after 1935.[9]

Though the New Mexico Constitution (1912) provided that laws would be published in both languages for 20 years and that practice was renewed several times, it ceased in 1949.[9][10] Accordingly, some describe New Mexico as officially bilingual,[11][12][13] but others disagree.[9][14]

See also

References

- Cobos, Rubén (2003) "Introduction," A Dictionary of New Mexico & Southern Colorado Spanish (2nd ed.); Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press; ISBN 0-89013-452-9

- Hämäläinen, Pekka (2008). The Comanche Empire. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9.

- Great Cotton, Eleanor and John M. Sharp. Spanish in the Americas' Georgetown University Press, p. 278.

- This is also a feature of the Spanish spoken in the northern Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora, other northwestern states of Mexico, and western Andalusia.

- This is a feature of all Spanish American, Canarian, and Andalusian dialects.

- This is related to the change of Latin /f/- to Spanish /h/-, in which /f/ was pronounced as a labiodental [f], bilabial [ɸ], or glottal fricative [h], which was later deleted from pronunciation.

- New Mexico Code 1-16-7 (1981).

- New Mexico Code 14-11-13 (2011).

- Cobarrubias, Juan; Fishman, Joshua A. (1983). Progress in Language Planning: International Perspectives. Walter de Gruyter. p. 195. ISBN 90-279-3358-8. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

- Garcia, Ofelia (2011). Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. John Wiley & Sons. p. 167. ISBN 1-4443-5978-9. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

- The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. "Language Rights and New Mexico Statehood" (PDF). New Mexico Public Education Department. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "NMTCE New Mexico Teachers of English". New Mexico Council of Teachers of English. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "All About New Mexico". Sheppard Software. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- Bills, Garland D.; Vigil, Neddy A. (2008). The Spanish Language of New Mexico and Southern Colorado: A Linguistic Atlas. UNM Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-8263-4549-2. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

Sources

- Rubén Cobos. A Dictionary of New Mexico & Southern Colorado Spanish. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2003.

- Garland D. Bills. "New Mexican Spanish: Demise of the Earliest European Variety in the United States". American Speech (1997, 72.2): 154–171.

- Rosaura Sánchez. "Our linguistic and social context", Spanish in the United States: Sociolinguistic Aspects. Ed. Jon Amastae & Lucía Elías-Olivares. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982. 9–46.

- Carmen Silva-Corvalán. "Lengua, variación y dialectos". Sociolingüística y Pragmática del Español 2001: 26–63.

- L. Ronald Ross. "La supresión de la /y/ en el español chicano". Hispania (1980): 552–554.