San Bernardino, California

San Bernardino (/ˌsæn ˌbɜːrnəˈdiːnoʊ/) is a city located in the Inland Empire region of Southern California. The city serves as the county seat of San Bernardino County, California. As one of the Inland Empire's anchor cities, San Bernardino spans 81 square miles (210 km2) on the floor of the San Bernardino Valley to the south of the San Bernardino Mountains. As of 2019, San Bernardino has a population of 215,784[10][11] making it the 17th-largest city in California and the 102nd-largest city in the United States. The governments of Guatemala and Mexico have established consulates in the downtown area of the city.[12]

San Bernardino, California | |

|---|---|

City | |

.jpg)  Top to Bottom: San Bernardino Santa Fe Depot; San Bernardino County Court House; Western Downtown San Bernardino. | |

Flag  Seal  | |

| Nickname(s): SB; San Berdoo; Berdoo; Gate City; City on the Move; The Friendly City; The Heart of Southern California, The 'Dino (sl.) | |

Location within San Bernardino County | |

San Bernardino Location within Southern California  San Bernardino Location within California  San Bernardino Location within the United States | |

| Coordinates: 34°6′N 117°18′W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | San Bernardino |

| Incorporated | August 10, 1869[1] |

| Named for | Bernardino of Siena |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-manager |

| • Mayor | John Valdivia |

| • City council[2] | Theodore Sanchez Sandra Ibarra Juan Figueroa Fred Shorett Henry Nickel Bessine L. Richard James Mulvihill |

| • City manager | Andrea M. Miller[3] |

| • Treasurer | David C. Kennedy[4] |

| • City attorney | Gary D. Saenz[5] |

| Area | |

| • City | 62.45 sq mi (161.75 km2) |

| • Land | 62.12 sq mi (160.88 km2) |

| • Water | 0.34 sq mi (0.88 km2) 0.74% |

| Elevation | 1,053 ft (321 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 209,924 |

| • Estimate (2019)[9] | 215,784 |

| • Rank | 1st in San Bernardino County 17th in California 102nd in the United States |

| • Density | 3,473.94/sq mi (1,341.30/km2) |

| • Metro | 4,224,851 |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 92401–92408, 92410–92415, 92418, 92420, 92423, 92424, 92427 |

| Area code | 909, 840 |

| FIPS code | 06-65000 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1661375, 2411777 |

| Website | sbcity |

California State University, San Bernardino is located in the northwestern part of the city. The university also hosts the Coussoulis Arena and the Robert and Frances Fullerton Museum of Art. Other attractions in San Bernardino include ASU Fox Theatre,[13] the McDonald's Museum (located on the original site of the world's first McDonald's), the California Theatre, and the San Manuel Amphitheater, the largest outdoor amphitheater in the United States. In addition, the city is home to the Inland Empire 66ers minor-league baseball team, which plays their home games at San Manuel Stadium in downtown San Bernardino.[14]

In August 2012, San Bernardino became the largest city at the time to file for protection under Chapter 9 of the U.S. Bankruptcy code;[15][16] this was superseded by Detroit's filing in July 2013.[17][18] On December 2, 2015, a terrorist attack left 14 people dead and 22 seriously injured.

History

The city of San Bernardino, California, occupies much of the San Bernardino Valley, which indigenous tribespeople originally referred to as "The Valley of the Cupped Hand of God". The Tongva Indians also called the San Bernardino area Wa'aach in their language.[19] Upon seeing the immense geological arrowhead-shaped rock formation on the side of the San Bernardino Mountains, they found the hot and cold springs to which the "arrowhead" seemed to point.

19th century

Politana was the first Spanish settlement in the San Bernardino Valley, named for Bernardino of Siena. Politana was established May 20, 1810, as a mission chapel and supply station by the Mission San Gabriel in the ranchería of the Guachama Indians that lived on the bluff that is now known as Bunker Hill, near Lytle Creek. Two years later the settlement was destroyed by local tribesmen, following powerful earthquakes that shook the region. Several years later, the Serrano and Mountain Cahuilla rebuilt the Politana rancheria, and in 1819 invited the missionaries to return to the valley. They did and established the San Bernardino de Sena Estancia. Serrano and Cahuilla people inhabited Politana until long after the 1830s decree of secularization and the 1842 inclusion into the Rancho San Bernardino land grant of the José del Carmen Lugo family.[20]:37–41

The city of San Bernardino is one of the oldest communities in the state of California, and in its present-day location, was not largely settled until 1851, after California became a state. The first Anglo-American colony was established by pioneers associated with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or Mormons. Following the Mormon colonists purchase of Rancho San Bernardino, and the establishment of the town of San Bernardino in 1851, San Bernardino County was formed in 1853 from parts of Los Angeles County. Mormons laid out the town based on the "City of Zion" plan which was typical of Mormon urban planning. Cities are typically laid out with North-South, East-West streets in predetermined city block sizes with wide streets. Often cities are laid out with an alphabetical and numerical system typical for Mormon towns, with streets running alphabet letters for North-South streets and numbers for East-West streets.[21] Mormon colonists developed irrigated, commercial farming and lumbering, supplying agricultural produce and lumber throughout Southern California. The city was officially incorporated in 1857. Later that year, most of the colonists were recalled by Brigham Young in 1857 due to the Utah War. Once highly regarded in early California, news of the Mountain Meadows Massacre poisoned attitudes toward the Mormons. Some Mormons would stay in San Bernardino and some later returned from Utah, but a real estate consortium from El Monte and Los Angeles bought most of the lands of the old rancho and of the departing colonists. They sold these lands to new settlers who came to dominate the culture and politics in the county and San Bernardino became a typical American frontier town. Many of the new land owners disliked the sober Mormons, indulging in drinking at saloons now allowed in the town. Disorder, fighting and violence in the vicinity became common, reaching a climax in the 1859 Ainsworth - Gentry Affair.

In 1860 a gold rush began in the mountains nearby with the discovery of gold by William F. Holcomb in Holcomb Valley early 1860. Another strike followed in the upper reach of Lytle Creek. By the 1860s, San Bernardino had also became an important trading hub in Southern California. The city already on the Los Angeles – Salt Lake Road, became the starting point for the Mojave Road from 1858 and Bradshaw Trail from 1862 to the mines along the Colorado River and within the Arizona Territory in the gold rush of 1862-1864.

Near San Bernardino is a naturally formed arrowhead-shaped rock formation on the side of a mountain. It measures 1375 feet by 449 feet. According to the Native American legend regarding the landmark arrowhead, an arrow from Heaven burned the formation onto the mountainside in order to show tribes where they could be healed. During the mid-19th century, "Dr." David Noble Smith claimed that a saint-like being appeared before him and told of a far-off land with exceptional climate and curative waters, marked by a gigantic arrowhead. Smith's search for that unique arrowhead formation began in Texas, and eventually ended at Arrowhead Springs in California in 1857. By 1889, word of the springs, along with the hotel on the site (and a belief in the effect on general health of the water from the springs) had grown considerably. Hotel guests often raved about the crystal-clear water from the cold springs, which prompted Seth Marshall to set up a bottling operation in the hotel's basement. By 1905, water from the cold springs was being shipped to Los Angeles under the newly created "Arrowhead" trademark.

Indigenous people of the San Bernardino Valley and Mountains were collectively identified by Spanish explorers in the 19th century as Serrano, a term meaning highlander. Serrano living near what is now Big Bear Lake were called Yuhaviatam, or "People of the Pines". In 1866, to clear the way for settlers and gold miners, state militia conducted a 32-day campaign slaughtering men, women, and children.[22] Yuhaviatam leader Santos Manuel guided his people from their ancient homeland to a village site in the San Bernardino foothills. The United States government in 1891 established it as a tribal reservation and named it after Santos Manuel.

In 1867, the first Chinese immigrants arrived in San Bernardino.

In 1883, California Southern Railroad established a rail link through San Bernardino between Los Angeles and the rest of the country.

20th century

_and_the_Stewart_Hotel%2C_San_Bernardino%2C_ca.1905_(CHS-5241).jpg)

In 1905, the city of San Bernardino passed its first charter.

Norton Air Force Base was established during World War II.

In 1940, Richard and Maurice McDonald founded McDonald's, along with its innovative restaurant concept, in the city.[23]

In 1980, the Panorama Fire destroyed 284 homes.

San Bernardino won the All-America City award in 1977,[24] but the city subsequently went into a long decline and has only recently begun to recover from the three recessions of the late 20th/early 21st centuries.

In 1994, Norton Air Force Base closed to become San Bernardino International Airport.

21st century

In October 2003, another wildfire, the Old Fire, destroyed over 1,000 homes.

In August 2012, San Bernardino filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy, with more than $1 billion in debt.[25] The move froze the city's payments to creditors, including its pension payments to the California Public Employees Retirement System for nearly a year. Key changes the city made during the bankruptcy process included: outsourcing its fire department to the county and re-writing the city's charter to provide a more clear chain of command. Following a judge's approval, the city emerged from bankruptcy in February 2017, making it one of the longest municipal bankruptcies in the United States.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 59.6 square miles (154 km2), of which 59.2 square miles (153 km2) is land and 0.4 square miles (1.0 km2), or 0.74%, is water.

The city lies in the San Bernardino foothills and the eastern portion of the San Bernardino Valley, roughly 60 miles (97 km) east of Los Angeles. Some major geographical features of the city include the San Bernardino Mountains and the San Bernardino National Forest, in which the city's northernmost neighborhood, Arrowhead Springs, is located; the Cajon Pass adjacent to the northwest border; City Creek, Lytle Creek, San Timoteo Creek, Twin Creek, Warm Creek (as modified through flood control channels) feed the Santa Ana River, which forms part of the city's southern border south of San Bernardino International Airport.

San Bernardino is unique among Southern Californian cities because of its wealth of water, which is mostly contained in underground aquifers. A large part of the city is over the Bunker Hill Groundwater Basin, including downtown. This fact accounts for a historically high water table in portions of the city, including at the former Urbita Springs, a lake which no longer exists and is now the site of the Inland Center Mall. Seccombe Lake, named after a former mayor, is a manmade lake at Sierra Way and 5th Street. The San Bernardino Valley Municipal Water District ("Muni") has plans to build two more large, multi-acre lakes north and south of historic downtown in order to reduce groundwater, mitigate the risks of liquefaction in a future earthquake, and sell the valuable water to neighboring agencies.

The city has several notable hills and mountains; among them are Perris Hill (named after Fred Perris, an early engineer, and the namesake of Perris, California); Kendall Hill (which is near California State University); and Little Mountain, which rises among Shandin Hills (generally bounded by Sierra Way, 30th Street, Kendall Drive, and Interstate 215).

Freeways act as significant geographical dividers for the city of San Bernardino. Interstate 215 is the major east-west divider, while State Route 210 is the major north-south divider. Interstate 10 is in the southern part of the city. Other major highways include State Route 206 (Kendall Drive and E Street); State Route 66 (which includes the former U.S. 66); State Route 18 (from State Route 210 north on Waterman Avenue to the northern City limits into the mountain communities), and State Route 259, the freeway connector between State Route 210 and I-215.

Climate

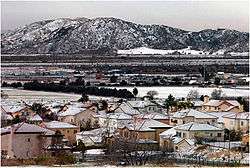

San Bernardino features a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Csa in the Köppen climate classification) with mild winters and hot, dry summers. Relative to other areas in Southern California, winters are colder, with frost and with chilly to cold morning temperatures common. The particularly arid climate during the summer prevents tropospheric clouds from forming, meaning temperatures rise to what is considered by NOAA scientists as Class Orange. Summer thus has temperatures approaching those typical of hot desert climates, with the highest recorded summer temperature at 118 °F (47.8 °C) on July 6, 2018.[26] In the winter, snow flurries occur upon occasion. San Bernardino gets an average of 16 inches (406 mm) of rain, hail, or light snow showers each year. Arrowhead Springs, San Bernardino's northernmost neighborhood gets snow, heavily at times, due to its elevation of about 3,000 feet (910 m) above sea level.

The seasonal Santa Ana winds are felt particularly strongly in the San Bernardino area as warm and dry air is channeled through nearby Cajon Pass at times during the autumn months. This phenomenon markedly increases the wildfire danger in the foothills, canyon, and mountain communities that the cycle of cold, wet winters and dry summers helps create.

According to the LA Times San Bernardino County has highest levels of ozone in the United States, averaging 102 parts per billion.[27]

| Climate data for San Bernardino, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 68.4 (20.2) |

69.2 (20.7) |

72.7 (22.6) |

77.8 (25.4) |

83.4 (28.6) |

90.1 (32.3) |

96.2 (35.7) |

97.3 (36.3) |

92.8 (33.8) |

84.0 (28.9) |

74.3 (23.5) |

67.1 (19.5) |

81.1 (27.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 55.3 (12.9) |

56.4 (13.6) |

59.2 (15.1) |

63.5 (17.5) |

68.9 (20.5) |

74.3 (23.5) |

79.9 (26.6) |

80.7 (27.1) |

76.8 (24.9) |

69.1 (20.6) |

59.9 (15.5) |

54.1 (12.3) |

66.5 (19.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 42.1 (5.6) |

43.6 (6.4) |

45.7 (7.6) |

49.2 (9.6) |

54.3 (12.4) |

58.5 (14.7) |

63.6 (17.6) |

64.2 (17.9) |

60.8 (16.0) |

54.1 (12.3) |

45.5 (7.5) |

41.1 (5.1) |

51.9 (11.1) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.15 (80) |

4.06 (103) |

2.53 (64) |

1.02 (26) |

.25 (6.4) |

.07 (1.8) |

.03 (0.76) |

.13 (3.3) |

.25 (6.4) |

.82 (21) |

1.29 (33) |

2.41 (61) |

16.01 (406.66) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.0 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 3.2 | 1.7 | .6 | .5 | .5 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 38.3 |

| Source: NOAA[28] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 1,673 | — | |

| 1890 | 4,012 | 139.8% | |

| 1900 | 6,150 | 53.3% | |

| 1910 | 12,779 | 107.8% | |

| 1920 | 18,721 | 46.5% | |

| 1930 | 37,481 | 100.2% | |

| 1940 | 43,646 | 16.4% | |

| 1950 | 63,058 | 44.5% | |

| 1960 | 91,922 | 45.8% | |

| 1970 | 106,869 | 16.3% | |

| 1980 | 118,794 | 11.2% | |

| 1990 | 164,164 | 38.2% | |

| 2000 | 185,401 | 12.9% | |

| 2010 | 209,924 | 13.2% | |

| Est. 2019 | 215,784 | [9] | 2.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[29] | |||

| Racial composition | 2010[30] | 1990[31] | 1970[31] | 1940[31] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 45.6% | 60.6% | 83.7% | 97.8% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 19.0% | 45.5% | 65.6%[32] | n/a |

| Black or African American | 15.0% | 16.0% | 14.0% | 1.5% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 60.0% | 34.6% | 20.3%[32] | n/a |

| Asian | 4.0% | 4.0% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

.png)

2010

The 2010 United States Census[33] reported that San Bernardino had a population of 209,924. The population density was 3,519.6 people per square mile (1,358.9/km2). The racial makeup of San Bernardino was 95,734 (45.6%) White (19.0% Non-Hispanic White),[34] 31,582 (15.0%) African American, 2,822 (1.3%) Native American, 8,454 (4.0%) Asian, 839 (0.4%) Pacific Islander, 59,827 (28.5%) from other races, and 10,666 (5.1%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 125,994 persons (60.0%).[34]

The Census reported that 202,599 people (96.5% of the population) lived in households, 3,078 (1.5%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 4,247 (2.0%) were institutionalized.

There were 59,283 households, out of which 29,675 (50.1%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 25,700 (43.4%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 13,518 (22.8%) had a female householder with no husband present, 5,302 (8.9%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 5,198 (8.8%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 488 (0.8%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 11,229 households (18.9%) were made up of individuals and 4,119 (6.9%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.42. There were 44,520 families (75.1% of all households); the average family size was 3.89.

The population was spread out with 67,238 people (32.0%) under the age of 18, 26,654 people (12.7%) aged 18 to 24, 56,221 people (26.8%) aged 25 to 44, 43,277 people (20.6%) aged 45 to 64, and 16,534 people (7.9%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 28.5 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.0 males.

There were 65,401 housing units at an average density of 1,096.5 per square mile (423.4/km2), of which 29,838 (50.3%) were owner-occupied, and 29,445 (49.7%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 3.2%; the rental vacancy rate was 9.5%. 102,650 people (48.9% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 99,949 people (47.6%) lived in rental housing units.

According to the 2010 United States Census, San Bernardino had a median household income of $39,097, with 30.6% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[34]

Ethnic diversity

Western, central, and parts of eastern San Bernardino are home to mixed-ethnic working class populations, of which the Latino and African-American populations comprise the vast majority of the city. Historically, many Latinos, primarily Mexican-Americans and Mexicans, lived on Mount Vernon Avenue on the West Side.[35] Since the 1960s, the Medical Center (formerly known as Muscoy) and Base Line corridors were mostly black, in particular in the east side and west side areas centering on public housing projects Waterman Gardens and the public housing on Medical Center drive. The heart of the Mexican-American community is on the West and Southside of San Bernardino, but is slowly expanding throughout the entire city.[36][37] San Bernardino's only Jewish congregation moved to Redlands in December 2009.[38] Some Asian Americans live in and around the city of San Bernardino, as in a late 19th-century-era (gone) Chinatown and formerly Japanese-American area in Seccombe Park on the east end of downtown, and a large East-Asian community in North Loma Linda. Others live in nearby Loma Linda to the south across the Santa Ana River. Filipinos are the largest Asian ethnic group in San Bernardino.[39] There is an Italian community in San Bernardino.[40] There is a rapid increase of Guatemalan immigrants in San Bernardino and the Inland Empire.[41] The white population in San Bernardino has declined while the Hispanic and Asian population increased.[42]

Economy

Government, retail, and service industries dominate the economy of the city of San Bernardino. From 1998 to 2004, San Bernardino's economy grew by 26,217 jobs, a 37% increase, to 97,139. Government was both the largest and the fastest-growing employment sector, reaching close to 20,000 jobs in 2004. Other significant sectors were retail (16,000 jobs) and education (13,200 jobs).[43]

The city's location close to the Cajon and San Gorgonio passes, and at the junctions of the I-10, I-215, and SR-210 freeways, positions it as an intermodal logistics hub. The city hosts the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway's intermodal freight transport yard, the Yellow Freight Systems' cross-docking trucking center, and Pacific Motor Trucking. Large warehouses for Kohl's, Mattel, Pep Boys, and Stater Bros. have been developed near the San Bernardino International Airport.[43]

Over the last few decades, the city's riverfront district along Hospitality Lane has drawn much of the regional economic development away from the historic downtown of the city so that the area now hosts a full complement of office buildings, big-box retailers, restaurants, and hotels situated around the Santa Ana River.

The closing of Norton Air Force Base in 1994 resulted in the loss of 10,000 military and civilian jobs and sent San Bernardino's economy into a downturn that has been somewhat offset by more recent growth in the intermodal shipping industry. The jobless rate in the region rose to more than 12 percent during the years immediately after the base closing. As of 2007 households within one mile of the city core had a median income of only $20,480, less than half that of the Inland region as a whole.[44] Over 15 percent of San Bernardino residents are unemployed as of 2012, and over 40 percent are on some form of public assistance.[45] According to the US Census, 34.6 percent of residents live below the poverty level, making San Bernardino the poorest city for its population in California, and the second poorest in the US next to Detroit.[46]

Amazon.com has built a new 950,000-square-foot (22-acre) fulfillment warehouse on the south side of the airport, that opened in the fall of 2012, promising to create 1,000 new jobs, which will make it one of the city's largest employers. Reference no longer valid

Top employers

According to the city's 2010 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[47] the top employers in the city are:

| Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|

| California State University, San Bernardino | 2,500+ |

| Caltrans District 8 | 1,000+ |

| City of San Bernardino | 1,000+ |

| Community Hospital of San Bernardino | 1,000+ |

| San Bernardino City Unified School District | 1,000+ |

| San Bernardino County Sheriff's Department | 1,000+ |

| San Bernardino County Superintendent of Schools | 1,000+ |

| San Manuel Band of Mission Indians | 1,000+ |

| Stater Bros. Markets | 1,000+ |

| St. Bernardine Medical Center | 1,000+ |

| Wells Fargo Home Mortgage | 1,000+ |

| Omnitrans | 500–999 |

| San Bernardino County Public Works | 500–999 |

| San Bernardino Valley College | 500–999 |

Arts and culture

Annual events

San Bernardino hosts several major annual events, including: Route 66 Rendezvous,[48] a four-day celebration of America's "Mother Road" that is held in downtown San Bernardino each September; the Berdoo Bikes & Blues Rendezvous, held in the spring; the National Orange Show Festival,[49] a citrus exposition founded in 1911 and also held in the spring; and, the Western Regional Little League Championships held each August, as well as the annual anniversary of the birth of the Mother Charter of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club, Berdoo California Chapter.

Museums

The Robert V. Fullerton Museum of Art, located on the campus of California State University, San Bernardino, contains a collection of Egyptian antiquities, ancient pottery from present-day Italy, and funerary art from ancient China. In addition to the extensive antiquities on display, the museum presents contemporary art and changing exhibitions.

The Heritage House holds the collection of the San Bernardino Historic and Pioneer Society, while the San Bernardino County Museum of regional history in Redlands has exhibits relating to the city of San Bernardino as well.

The San Bernardino Railroad and History Museum is located inside the historic Santa Fe Depot. A Route 66 museum is located on the historic site of the original McDonald's restaurant.[50] It is at 1398 North E Street and West 14th Street.

Specialty museums include the Inland Empire Military Museum,[51] the American Sports Museum, and the adjacent WBC Legends of Boxing Museum.

Performing arts

- The 1928 California Theatre (San Bernardino), California Theater of the Performing Arts in downtown San Bernardino hosts an array of events, including concerts by the San Bernardino Symphony Orchestra, as well as touring Broadway theater productions presented by Theatrical Arts International, the Inland Empire's largest theater company.[52]

- San Manuel Amphitheater, originally Glen Helen Pavilion at the Cajon Pass is the largest amphitheater in the United States.

- National Orange Show Festival The National Orange Show Events Center contains: the Orange Pavilion; a stadium; two large clear-span exhibition halls; a clear-span geodesic dome; and several ballrooms.

- Coussoulis Arena in the University District is the largest venue of its type in San Bernardino and Riverside Counties.

- Sturges Center for the Fine Arts, including the 1924 Sturges Auditorium, hosts lectures, concerts, and other theater.[53]

- Roosevelt Bowl at Perris Hill presents outdoor theater by Junior University during the summer months.

- The historic 1929 Fox Theater of San Bernardino, located downtown and owned by American Sports University, has recently been restored for new use.

- The Lyric Symphony Orchestra in nearby Loma Linda, California presents concerts in the city and nearby communities.[54]

Resorts and tourism

San Bernardino is home to the historic Arrowhead Springs Hotel and Spa, located in the Arrowhead Springs neighborhood, which encompasses 1,916 acres (7.75 km2) directly beneath the Arrowhead geological monument that presides over the San Bernardino Valley. The resort contains hot springs, in addition to mineral baths and steam caves located deep underground. Long the headquarters for Campus Crusade for Christ, the site now remains largely vacant and unused since their operations moved to Florida.[55]

The $300 million Casino San Manuel, one of the few in southern California that does not operate as a resort hotel, is located approximately one mile from the Arrowhead Springs Hotel and Spa.

The city is also home to the Arrowhead Country Club and Golf Course.

In downtown, Clarion, adjacent to the San Bernardino Convention Center, is the largest hotel while the Hilton is the largest in the Hospitality Lane District.

Nicknames

San Bernardino has received many informal nicknames in its history. Of these, San Berdoo, S.B.D., S.B., San B., Dino, San Bernas, and Berdoo[56][57] are the most common but are sometimes considered derogatory or undignified. Other, more official nicknames include Gate City[58] (to reflect its proximity to Los Angeles, and location at the southern and western end of the Cajon Pass, leading to the High Desert and Las Vegas, Nevada); The Friendly City;[59][60] City on the Move;[59] and, most recently, The Heartbeat of U.S. Route 66.[61]

Sports

The California State University, San Bernardino (CSUSB) Coyotes compete at the NCAA Division II level in a variety of sports. San Bernardino Valley College competes in the CCCAA and is the only school to offer football at the collegiate level in San Bernardino.

CSUSB used to play their home baseball games at the downtown venue, Arrowhead Credit Union Park, but now play all their home games at the uptown venue, Fiscalini Field.[62]

San Bernardino has had other professional and semi-pro teams over the years, including the San Bernardino Jazz professional women's volleyball team, the San Bernardino Pride Senior Baseball team, and the San Bernardino Spirit California League Single A baseball team.

The Glen Helen Raceway has hosted off-road motorsport races such as rounds of the AMA Motocross Championship, Motocross World Championship and Lucas Oil Off Road Racing Series.

San Bernardino also hosts the BSR West Super Late Model Series at Orange Show Speedway. The series fields many drivers, including NASCAR Camping World Truck Series regular Ron Hornaday, who drove the No. 33 in a race on July 12, 2008.

Inland Empire 66ers

The city hosts the Inland Empire 66ers baseball club of the California League, which since 2011 has been the Los Angeles Angels Single A affiliate. The team was the Los Angeles Dodgers Single A affiliate from 2007 to 2010. The 66ers play at San Manuel Stadium in downtown San Bernardino.[14]

Parks and recreation

San Bernardino offers several parks and other recreation facilities. Perris Hill Park is the largest with Roosevelt Bowl, Fiscalini Field,[63] several tennis courts, a Y.M.C.A., a senior center, a shooting range, hiking trails, and a pool. Other notable parks include: the Glen Helen Regional Park, operated by the County of San Bernardino, is located in the northernmost part of the city. Blair Park is another midsized park near the University District, it is home to a well known skate park and various hiking trails on Shandin Hills, also known as Little Mountain.

Government

Local government

According to the city's 2012 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, the city's various funds had $313.6 million in Revenues, $298.5 million in expenditures, $1,113.3 million in total assets, $449.6 million in total liabilities, and $181.0 million in cash and investments.[47]

The city of San Bernardino is a charter city, a form of government under California that allows limited home-rule, in that it can pass its own laws not in conflict with state law, such as when state law is silent, or expressly allows municipal regulations of areas of local concern. San Bernardino became a charter city in 1905, the most current charter was passed in 2016.

The city of San Bernardino is a council-manager city with a full-time mayor elected by the city at large. The council consists of seven wards which are elected to four-year terms. The charter also created the San Bernardino City Unified School District, a legally separate agency, and the Board of Water Commissioners, a semi-autonomous, but legally indistinct commission, and a Board of Library Trustees. The City Manager is responsible for all department heads, except for the fire and police chiefs. Previously, the San Bernardino Municipal Code recognized a City Administrator.

When the city originally adopted a ward system, there were five wards. In the 1960s, the Council was expanded to seven wards. The boundaries are adjusted with each federal census. The current council is:[4]

- Mayor: John Valdivia

- First Ward: Theodore Sanchez

- Second Ward: Sandra Ibarra

- Third Ward: Juan Figueroa

- Fourth Ward: Fred Shorrett

- Fifth Ward: Henry Nickel

- Sixth Ward: Bessine L. Richard

- Seventh Ward: James L. Mulvihill

As per California law, all city positions are nonpartisan. Bob Holcomb (1922–2010) was the longest-serving mayor of San Bernardino to date, holding the office from 1971 until 1985 and again from 1989 to 1993.[64][65]

San Bernardino's legal community has two centers: downtown and Hospitality Lane. Criminal, family, and government lawyers are centered downtown, while local civil firms and outposts of state and national firms, corporate, and insurance defense firms, are located along Hospitality Lane. The government of Mexico has a consulate in downtown San Bernardino on the southeast corner of Third Street and D Street. Citizens of Mexico can obtain a Matrícula Consular, which many governments and businesses use in lieu of U.S. photo identification.

Mayors

| Mayor | Begin term | End term |

|---|---|---|

| Amasa M. Lyman | 1854 | 1854 |

| Charles C. Rich | 1855 | 1855 |

| Hiram Merritt Barton | May 8, 1905 | June 24, 1907 |

| John J. "Pop" Hanford | June 24, 1907 | May 10, 1909 |

| Samuel W. McNabb | May 10, 1909 | May 8, 1911 |

| Joseph S. Bright | May 8, 1911 | May 12, 1913 |

| Joseph W. Catick | May 12, 1913 | May 10, 1915 |

| George H. Wixom | May 10, 1915 | May 12, 1919 |

| John A. Henderson | May 12, 1919 | May 9, 1921 |

| Samuel W. McNabb | May 9, 1921 | February 9, 1925 |

| Grant Holcomb | February 9, 1925 | May 9, 1927 |

| Ira N. Gilbert | May 9, 1927 | May 13, 1929 |

| John C. Ralphs Jr. | May 13, 1929 | May 11, 1931 |

| Ira N. Gilbert | May 11, 1931 | May 8, 1933 |

| Ormond W. Seccombe | May 8, 1933 | May 3, 1935 |

| Clarence T. Johnson | May 13, 1935 | May 8, 1939 |

| Henry C. McAllister | May 8, 1939 | May 12, 1941 |

| Will C. Seccombe | May 12, 1941 | May 12, 1947 |

| James E. Cunningham Sr. | May 12, 1947 | December 15, 1950 |

| Clarence T. Johnson | December 16, 1950 | May 14, 1951 |

| George C. Blair | May 14, 1951 | May 9, 1955 |

| Raymond H. Gregory | May 9, 1955 | December 31, 1957 |

| Elwood D. "Mike" Kremer | December 31, 1957 | May 11, 1959 |

| Raymond H. Gregory | May 11, 1959 | May 8, 1961 |

| Donald G. "Bud" Mauldin | May 8, 1961 | May 10, 1965 |

| Al C. Ballard | May 10, 1965 | May 10, 1971 |

| W. R. "Bob" Holcomb | May 10, 1971 | June 2, 1985 |

| Evlyn Wilcox | June 3, 1985 | June 5, 1989 |

| W. R. "Bob" Holcomb | June 5, 1989 | June 7, 1993 |

| Tom Minor | June 7, 1993 | March 2, 1998 |

| Judith Valles | March 2, 1998 | March 6, 2006 |

| Patrick J. Morris | March 6, 2006 | March 3, 2014 |

| R. Carey Davis | March 3, 2014 | December 19, 2018 |

| John Valdivia | December 19, 2018 | Incumbent |

Bankruptcy

On July 10, 2012, the City Council of San Bernardino decided to seek protection under Chapter 9, Title 11, United States Code, making it the third California municipality to do so in less than two weeks (after Stockton and the town of Mammoth Lakes), and the second-largest ever. According to state law, the city would normally have to negotiate with creditors first, but, because they declared a fiscal emergency in June, that requirement did not apply.[15][16] The case was filed on August 1.[18]

Municipal code

As a charter city, San Bernardino may make and enforce its own laws as long as they are not in conflict with the laws of the State of California. These rules have been codified as the San Bernardino Municipal Code. Violations of the code, punishable as a misdemeanor or infraction (or both) are prosecuted by the City Attorney's Office in the San Bernardino County Superior Court. The city also has two administrative processes for violations of the code, as well as other adopted codes, like the California Building Code and the California Fire Code. One process is an administrative citation system, similar to a parking ticket, with a pay or contest procedure. The other is an administrative hearing process, generally used by the Code Enforcement Department for prosecuting multiple code violations.

Downtown San Bernardino revitalization efforts

.jpg)

In June 2009, the city's Economic Development Agency, presented the San Bernardino City Council with the Downtown Core Vision/Action Plan[67]– a guide for revitalizing Downtown San Bernardino for the next 10 years. The plan, which the city council approved to support, is the culmination of a year of research, community participation, and planning led by the city's EDA and the urban planning firm EDAW which has worked on master planning across the globe for downtown areas that include Milan, Italy; London, England; New York, New York; and Denver, Colorado, to name a few.

A driving force in the initial phase of the revitalization efforts is the development of an arts and culture district in the heart of Downtown San Bernardino. This effort is being anchored by the historic and iconic California Theatre,[52] which has been in continuous operation since first opening its doors in 1928. California-based Maya Cinemas, which is adjacent to California Theatre, is in the process of renovating the former CinemaStar movie theatre. These two entertainment facilities are the foundation of what will become a vibrant center for the arts and culture.

Joint-power authorities

San Bernardino shares certain powers with other agencies to form legally separate entities known as joint-power authorities under California law. These include Omnitrans, which provides transportation throughout the east and west valleys of San Bernardino County, SANBAG, which coordinates transportation projects throughout the county, and the Inland Valley Development Agency, which is responsible for redevelopment of the areas around the San Bernardino International Airport.

County seat

San Bernardino is the county seat of San Bernardino County, the largest organized county in the contiguous United States by area, but smaller than several boroughs and census areas in Alaska. Various state courts (for civil, criminal and juvenile trials) operate under the auspices of the Superior Court, San Bernardino District (formerly Central Division prior to the unification of the Superior and Municipal Courts in 1998). Currently, the Superior Court of California county courthouse is located at 351 North Arrowhead Avenue. It consists of a four-story building of steel and concrete construction built in 1927. A six-story addition was added in the 1950s. Currently, the 1926 structure is being retrofitted. A new courthouse, located at 247 West Third Street, opened in 2014, which houses civil courts.

Juvenile Court and Juvenile Hall are located in a county enclave adjacent to the city on Gilbert Street, near the site of the former County Hospital.

The County's District Attorney and the Public Defender both have their main offices on Mountain View Avenue, directly east of the Courthouse.

The California Court of Appeal Fourth District, Division Two used to be located in San Bernardino, but moved to Riverside in the 1990s. Federal cases (including Bankruptcy) are also heard in Riverside courthouses.

Public safety

The 1905 Charter created the San Bernardino Police Department and chief of police; before 1905, there was a position of city marshal. The current charter places the chief of police under the direction of the mayor.

The San Bernardino City Fire Department was founded in 1878 and dissolved on July 1, 2016, to be taken over by the San Bernardino County Fire District.[68]

Charter Section 186 requires that the monthly salaries of police and fire local safety members be the average of like positions at ten comparable cities in California.[69] Thus, if the average goes up in other cities, the compensation of the local safety employees automatically rises.

Over 90 percent of local police officers do not live within the city limits.[70]

Recent police efforts include joint patrols with the San Bernardino County Sheriff's Department and the California Highway Patrol. As of November 2006,[71] Part 1 Crime (Murders, Rape, Robbery, Assault, Burglary and Theft) was down 14.07 percent from 2005. Stricter enforcement caused a rise in both juvenile and adult arrests.[72]

San Bernardino has long battled high crime rates. According to statistics published by Morgan Quitno, San Bernardino was the 16th most dangerous US city in 2003,[73] 18th in 2004[74] and 24th in 2005. San Bernardino's murder rate was 29 per 100,000 in 2005, the 13th highest murder rate in the country and the third highest in the state of California after Compton and Richmond.[75] Police efforts have significantly reduced crime in 2008[76] and a major drop collectively since 1993 when the city's murder rate placed ninth in the nation.[77] Thirty two killings occurred in 2009, a number identical to 2008 and the lowest murder rate in San Bernardino since 2002, but only a third of cases led to arrests.[78][79] According to findings by the U.S. Census Bureau, San Bernardino was among the most poverty-stricken cities in the nation, second nationally behind Detroit.[80]

Jails

The San Bernardino Police Department has a holding area, but pre-trial arrested suspects are transported to the West Valley Detention Center in Rancho Cucamonga. Sentenced criminals are held at the Glen Helen Rehabilitation Center, in the northern limits of the city in the Verdemont neighborhood. While the Central Detention Center, located at 630 East Rialto Avenue in San Bernardino, served as the main jail from 1971–1992, today it mostly serves federal prisoners under contract.

State and federal representation

In the California State Senate, San Bernardino is split between the 20th Senate District, represented by Democrat Connie Leyva, and the 23rd Senate District, represented by Republican Mike Morrell.[81] In the California State Assembly, it is split between the 40th Assembly District, represented by Democrat James Ramos, and the 47th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Eloise Reyes.[82]

In the United States House of Representatives, San Bernardino is in California's 31st congressional district, which has a Cook PVI of D+5[83] and is represented by Democrat Pete Aguilar.[84]

Education

San Bernardino is primarily served by the San Bernardino City Unified School District, the eighth largest district in the state,[85] although it is also served by Rim of the World (far north, mountains), Redlands (far south east) and Rialto (far west) Unified School Districts.

Colleges and universities

- California University of Science and Medicine

- California State University, San Bernardino

- San Bernardino Valley College

- The Art Institute of California - Inland Empire

- American Sports University

- Inland Empire Job Corps Center

- UEI College

- Summit Career College

High schools

The district, as signified by its name, has elementary, intermediate, and high schools. The comprehensive high schools are:

- Aquinas High School (San Bernardino, California)

- Arroyo Valley High School

- Cajon High School

- San Andreas High School

- San Bernardino High School

- Pacific High School (San Bernardino)

- Public Safety Academy Charter High School

- Middle College High School

- San Gorgonio High School

- Sierra High School

- Casa Ramona Academy for Technology, Community and Education

- Provisional Accelerated Learning Charter Academy

- Rim of the World High School

- Indian Springs High School

Media

San Bernardino is part of the Los Angeles Nielsen area. As such, most its residents receive the same local television and radio stations as residents of Los Angeles. KVCR-DT, a PBS affiliate operated by the San Bernardino Community College District, is the only local San Bernardino television station. KPXN, the Los Angeles Ion Television network affiliate, is licensed to San Bernardino, but contains no local content. Most of the northern section of San Bernardino cannot receive over-the-air television broadcasts from Los Angeles because Mount Baldy, and other San Gabriel Mountain peaks, block transmissions from Mount Wilson. Since the 1960s, most North San Bernardino residents have required cable television to obtain television. Today, the city has one main cable franchise: the city has Charter Communications. Mountain Shadow Cable is a small local company that provides services to the eponymous mobile home park. DBS satellite also has a presence. Local programming is handled by the city's Public, educational, and government access (PEG) cable TV channel KCSB-TV.

Historically, San Bernardino has had a number of newspapers. Today, the San Bernardino Sun, founded in 1894 (but was the continuation of an earlier paper) publishes in North San Bernardino, and has a circulation area roughly from Yucaipa to Fontana, including the mountain communities. Many older residents refer to the Sun as the Sun-Telegram, its name when it merged with the afternoon Telegram in the 1960s. The Precinct Reporter has been publishing weekly since 1965, primarily serving African American residents. Its circulation also includes Riverside County and Pomona Valley. There is also the Black Voice News that previously served Riverside has been in the area over 30 years and has more recently served African Americans that live in the community. Another local newspaper centered mostly around the African American community is the Westside Story Newspaper, established in 1987. Their coverage area extends to the greater area of San Bernardino County. They currently operate locally and online. The Inland Catholic Byte is the newspaper of the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Bernardino. The Los Angeles Times is also widely circulated.

The Inland Empire also has its own Arbitron area. Therefore, there are several radio stations that broadcast in San Bernardino or other Inland Empire cities. These include top 40 station KHTI, country music station KFRG, NPR member station KVCR and news/talk/music station KCAA 1050 AM, with studios in the Carousel Mall. Other than government or media outlets, there is no major internet site made for the Inland Empire.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Roads and highways

San Bernardino has a system of mostly publicly maintained local streets, including major arterials, some private streets, state highways, and interstate highways.

The city's street system is laid out in a grid network, mostly aligned with the public land survey system. The major streets are north-south streets, from the west, are: Meridian Avenue, Mount Vernon Avenue, E Street, Arrowhead Avenue, Sierra Way, Waterman Avenue, Tippecanoe Avenue, Del Rosa Avenue, Sterling Avenue, Arden Avenue, Victoria Avenue, Palm Avenue, and Boulder Street. The major east-west streets, from the north, are: Northpark Boulevard, Kendall Avenue, 40th Street, Marshall Boulevard, 30th Street, Highland Avenue, Base Line (Street), 9th Street, 5th Street, 2nd Street, Rialto Avenue, Mill Street, Orange Show Road, and Hospitality Lane.

The state highways include:

Freeways include:

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Rail service

Amtrak's Southwest Chief, operating between Los Angeles and Chicago, has one daily train in each direction that stops at the San Bernardino station.

San Bernardino is served by the Metrolink regional rail service. Two lines serve the city: the Inland Empire-Orange County Line and the San Bernardino Line. The San Bernardino Transit Center in the downtown area is where passengers can connect with BRT, and regular bus service from MARTA, Omnitrans, and VVTA.[86]

Arrow is an under construction passenger rail link to neighboring Redlands that is expected to open in 2022. Trains will begin at the San Bernardino Transit Center and make an additional stop at Tippecanoe Avenue before continuing into Redlands.

Bus

The city of San Bernardino is a member of the joint-powers authority of Omnitrans and MARTA. A bus rapid transit corridor, called sbX Green Line, connects the north part of the city near California State University, San Bernardino and the Verdemont Hills area with the Jerry L. Pettis VA Medical Center in Loma Linda, CA.[87][88] Additional bus routes and on-demand shuttle service for the disabled and elderly is also provided by Omnitrans. MARTA provides a connection between downtown and the mountain communities.

Airports

San Bernardino International Airport is physically located within the city. The airport is the former site of Norton Air Force Base which operated from 1942 - 1994. In 1989, Norton was placed on the Department of Defense closure list and the majority of the closure occurred in 1994, with the last offices finally leaving in 1995.[89] Several warehouses have been, and continue to be, built in the vicinity. The facility, itself, is within the jurisdiction of the Inland Valley Development Agency, a joint powers authority, and the San Bernardino Airport Authority. Hillwood, a venture run by H. Ross Perot, Jr., is the master developer of the project, which it calls AllianceCalifornia. The airport does not currently offer commercial passenger service. However, both the domestic and international terminals have been completed and are ready for passenger service.[90]

Cemeteries

- Campo Santo Cemetery at West 27th Street between North D and North E Streets[91]

- Home of Eternity Cemetery[92]

- Mountain View Cemetery,[93] which contains the graves of James Earp, a member of the Earp family and heavy metal guitarist Randy Rhoads.

- Pioneer Memorial Cemetery,[94] which contains the grave of Ellis Eames, first mayor of Provo, Utah[95]

Notable people

Sister cities

San Bernardino has eleven sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International and the Mayor's office[96] of the City of San Bernardino:

|

See also

References

- "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- "City of San Bernardino - Common Council".

- "City Manager's Office". City of San Bernardino. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- "Elected Officials". City of San Bernardino. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- "City Attorney's Office". City of San Bernardino. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "San Bernardino". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

- "San Bernardino (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder - Results".

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- DAVID OLSON (March 7, 2014). "IMMIGRATION: Guatemala to open San Bernardino consulate". Press Enterprise. Archived from the original on March 17, 2014.

- "American Sports University". American Sports University. Archived from the original on June 24, 2012. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- "History - Inland Empire 66ers San Manuel Stadium". Inland Empire 66ers.

- "3rd Calif. city to file for bankruptcy in 1 month". CBS News. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- Church, Steven (August 17, 2012). "San Bernardino Bankruptcy Judge Sets Oct. 24 Deadline". BloombergBusinessWeek. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- "City of San Bernardino, California Chapter 9 Voluntary Petition" (PDF). PacerMonitor. PacerMonitor. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- Reid, Tim (August 2, 2012). "San Bernardino, California, files for bankruptcy with over $1 billion in debts". Reuters. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- Munro, Pamela, et al., Yaara' Shiraaw'ax 'Eyooshiraaw'a. Now You're Speaking Our Language: Gabrielino/Tongva/Fernandeño. Lulu.com: 2008.

- Caballeria y Collell, Juan, HISTORY OF SAN BERNARDINO VALLEY, from the padres to the pioneers, 1810-1851, Times-Index Press, San Bernardino, Cal., 1902.

- https://eom.byu.edu/index.php/City_Planning

- "History". San Manuel Band of Mission Indians. Archived from the original on August 23, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- Modern Marvels "Fast Food Tech"; History Channel; Viewed December 3, 2009

- "Past Winners". National Civic League. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- "San Bernardino, California, files for bankruptcy with over $1 billion in debts". Reuters. August 2, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- "Average Weather for San Bernardino, CA – Temperature and Precipitation". The Weather Channel. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- New attack on California's dirty air by Tony Barboza, LA Times Oct. 1, 2015

- "Station Name: CA SAN BERNARDINO F S 226". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "San Bernardino (city), California". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau.

- "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012.

- From 15% sample

- "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - San Bernardino city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- "San Bernardino (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". Archived from the original on November 25, 2005.

- Quinones, Sam (June 29, 2008). "Murder trial exposes gang intrigue, greed". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- "Obama inspires hope on Westside – San Bernardino County Sun". Sbsun.com. March 9, 2010. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "Inland get-out-the-vote effort tries personal contact". Archived from the original on September 21, 2009. Retrieved 2008-10-20.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Faturechi, Robert (January 25, 2010). "San Bernardino loses its Jewish congregation". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- https://www.pe.com/2012/05/26/filipino-cultural-celebration-in-san-bernardino/

- "San Bernardino has plenty of Italian connections". Daily News. August 29, 2011. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- https://www.pe.com/2012/03/18/immigration-guatemalans-flocking-to-inland-area/

- https://www.pe.com/2012/05/17/latino-population-up-whites-decline-in-san-bernardino/

- Advisory Services Panel (June 24–29, 2007). San Bernardino, California: Crossroads of the Southwest. Washington, D.C.: Urban Land Institute. Retrieved December 26, 2007.

- Brown, Josh (July 25, 2007). "San Bernardino's base redevelopment efforts take circuitous path". Press Enterprise. Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved December 26, 2007.

- Willon, Phil (July 12, 2012). "Plenty of blame on long road to San Bernardino bankruptcy". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- Romero, Dennis (October 17, 2011). "America's Second Poorest Big City is Right Here in Southern California: San Bernardino". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on December 21, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- "City of San Bernardino CAFR". Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- "19th Annual Stater Bros. Route 66 Rendezvous". Route-66.org. Archived from the original on August 1, 2007. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- NOS Festival Archived July 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Welcome to the Historic Site Of The First McDonalds". Archived from the original on October 12, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- "Inland Empire Military Museum". Sbsun.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "Home".

- "Sturges Center for the Fine Arts".

- "Lyric Symphony Orchestra". December 4, 2010.

- "California Historical Landmarks: San Bernardino County". Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- "Used since the 1870s". angeles.sierraclub.org. February 25, 2003. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "Practical Presbyterian, Time Magazine, April 23, 1951". Time. April 23, 1951. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- See The San Bernardino Daily Sun, July 1918 quoted at Santa Fe Depot and the Railroads

- Interview of Edward Thomann on January 9, 2003 by Professor Joyce Hanson, for the San Bernardino Oral History Project, January 9, 2003"Historical Treasures of San Bernardino". Archived from the original on January 13, 2009. Retrieved 2007-03-03.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "About San Bernardino". Archived from the original on October 23, 2002.

- The Convention and Visitor's Bureau created this slogan, but no longer uses it

- Events Calendar

- "Fiscalini Field". Digitalballparks.com. September 15, 2002. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- Koren, James Rufus (November 29, 2010). "Ex-mayor of San Bernardino dies at 88". The San Bernardino Sun. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- Edwards, Andrew (December 9, 2010). "Former SB mayor W.R. "Bob" Holcomb laid to rest". Contra Costa Times. Archived from the original on December 13, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- Mayors of San Bernardino, City of San Bernardino (accessed December 4, 2015).

- City of San Bernardino EDA, Pirih Productions, and Brostrom Software Solutions. "Downtown Core Vision". Sbrda.org. Archived from the original on October 9, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2011.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "San Bernardino City Fire Department. Stations". Ci.san-bernardino.ca.us. Archived from the original on March 5, 2007. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- City of San Bernardino, Charter section 186, San Bernardino Municipal Code section 1.28.020

- Brown, Hardy (March 15, 2007). "Brinker, Derry, Kelley & McCammack 'Wrapped Up, Tied Up, Tangled Up' . . . Ethics Gone". San Bernardino Black Voice News. Archived from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- "November 2006 Part 1 Crime in San Bernardino". Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "Juvenile and adult arrests in San Bernardino". Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "Morgan Quitno. 2005 city crime statistics". Morganquitno.com. Archived from the original on December 25, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "Comunidad Segura. Lis Horta Moriconi, 13/09/2006. California's San Bernardino aims for a turnaround with Operation Phoenix". Comunidadesegura.org. September 13, 2006. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "Infoplease. Crime Data. 2005 Murder Rate in Cities". Infoplease.com. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- Brooks, Ricahrd (July 10, 2008). "Crime falls nearly 10 percent in San Bernardino". Press Enterprise. Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-20.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Jet. FBI report lists cities with highest murder rates in 1993". Findarticles.com. December 19, 1994. Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- Larocco, Paul (September 20, 2008). "2007 data: San Bernardino has state's 4th highest murder rate for cities above 10,000 people". Press Enterprise. A. H. Belo. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- Larocco, Paul (January 8, 2010). "Inland's largest cities log lower or near-identical killing totals in 2009". Press Enterprise. A. H. Belo. Archived from the original on September 7, 2012. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- Dulaney, Josh (October 16, 2011). "San Bernardino among most poverty-stricken in nation". San Bernardino Sun. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- "Communities of Interest — City". California Citizens Redistricting Commission. Archived from the original on October 23, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- "Communities of Interest — City". California Citizens Redistricting Commission. Archived from the original on October 23, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- "Partisan Voting Index: Districts of the 113th Congress" (PDF). The Cook Political Report. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 5, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- "California's 31st Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- "San Bernardino City Unified School District". Archived from the original on May 4, 2012.

- Begley, Doug (June 4, 2009). "E Street transit center chosen for Metrolink plan". Press Enterprise. A. H. Belo. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- "Pep Rally Celebrates sbX Completion". Omnitrans. April 24, 2014. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- About sbX Archived August 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Norton Air Force Base

- Roberts, Charles (August 4, 2009). "Jet Service comes to SBD". Highland News. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved August 4, 2009.(registration required)

- "Campo Santo Cemetery". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Home of Eternity Cemetery". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Mountain View Cemetery". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Pioneer Memorial Cemetery". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "City of San Bernardino - Pioneer Memorial Cemetery".

- "Mayor's Office – Sister Cities". Ci.san-bernardino.ca.us. Archived from the original on March 5, 2007. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

Further reading

- Books

- Edward Leo Lyman, San Bernardino: The Rise and Fall of a California Community, Signature Books, 1996.

- Walter C. Schuiling, San Bernardino County: Land of Contrasts, Windsor Publications, 1984

- Nick Cataldo, Images of America: San Bernardino, California, Arcadia Publishing, 2002

- Articles

- James Fallows (May 2015), What It's Like When Your City Goes Broke. "San Bernardino, California, is poor, has a high unemployment rate, is affected by drought, and is in bankruptcy court. But its real problem is something else."

External links

- Official website

- California Welcome Center in San Bernardino

- City of San Bernardino at the Wayback Machine (archived November 11, 1998)