Brazilian Americans

Brazilian Americans (Portuguese: brasileiros-americanos, norte-americanos de origem brasileira or estadunidenses de origem brasileira) are Americans who are of full or partial Brazilian ancestry. They are relatively new arrivals. for the 1960 Census only counted 27,855 Brazilians. The first major immigration came after 1986, when 1.4 million Brazilians left their homes for various countries. By 2001 about one million lived in the U.S. Nearly half live in New York, Massachusetts, and New Jersey, with significant populations in the south as well.[4]

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 371,529[1] 0.11% of the U.S. population (2012) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Miami metropolitan area, Orlando metropolitan area, New York City metropolitan area and Northern New Jersey,[2] Boston metropolitan area,[3] Dallas–Fort Worth, Wisconsin, Connecticut, Philadelphia, Houston, Los Angeles, Atlanta. Growing populations in Chicago, Colorado and Louisiana | |

| Languages | |

| American English, Brazilian Portuguese, Indigenous Brazilian languages, European languages (German, Venetian, Polish, etc.), Asian languages (Japanese, etc.) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Roman Catholicism Minority: Protestantism, Mormonism, Spiritism, Candomblé, Quimbanda, Umbanda, Buddhism, Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Brazilian Canadians, other Brazilian diaspora |

Estimated numbers

There were an estimated 371,529 Brazilian Americans as of 2012, according to the United States Census Bureau.[1] Another source gives an estimate of some 800,000 Brazilians living in the U.S. in 2000,[5] while still another estimates that as of 2008 some 1,100,000 Brazilians live in the United States, 300,000 of them in Florida.[6] According to the 2016 American Community Survey, There are a total of 42,193,781 foreign born persons in the United States. From the 42.2 million immigrants, 350,091 are Brazilians, corresponding 0.83% (350,091/42.2million) of the foreign born population.[7]

While the official United States Census category of Hispanic or Latino includes persons of South American origin, it also refers to persons of "other Spanish culture," creating some ambiguity about whether Brazilians, who are of South American origin but do not have a Spanish culture, qualify as Latino, and they are not "Hispanic" (although the term encompasses the entire Iberian Peninsula but usually refers a culture derived from Spain as in Spanish language), they are "Latino" (which is short for latinoamericano).[8][9][10]

Other U.S. government agencies, such as the Small Business Administration and the Department of Transportation, specifically include Brazilians within their definitions of Hispanic and Latino for purposes of awarding minority preferences by defining Hispanic Americans to include persons of South American ancestry or persons who have Portuguese cultural roots.[11][12]

History

People from what is now Brazil (from ancient João Pessoa and Recife under Dutch control in Northeast Brazil - Paraíba and Pernambuco states) are recorded among the Refugees and Settlers that arrived in New Netherland in what is now New York City in the 17th Century among the Dutch West India Company settlers. The first arrivals of Brazilian emigres were formally recorded in the 1940s. Previously, Brazilians were not identified separately from other South Americans. Of approximately 234,761 South American emigres arrived in the United States between 1820 and 1960, at least some of them were Brazilian. The 1960 United States Census report recorded 27,885 Americans of Brazilian ancestry.[13]

From 1960 until the mid-1980s, between 1,500 and 2,300 Brazilian immigrants arrived in the United States each year. During the mid-1980s, economic crisis struck Brazil. As a result, between 1986 and 1990 approximately 1.4 million Brazilians emigrated to other parts of the world. It was not until this time that Brazilian emigration reached significant levels. Thus, between 1987 and 1991, an estimated 20,800 Brazilians arrived in the United States. A significant number of them, 8,133 Brazilians, arrived in 1991. The 1990 U.S. Census Bureau recorded that there are about 60,000 Brazilians living in the United States. However, other sources indicate that there are nearly 100,000 Brazilians living in the New York City metropolitan area (including Northern New Jersey) alone, in addition to sizable Brazilian communities in Atlanta, Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, Miami, Houston, and Phoenix.[13]

There are many hypothesis regarding the formation of Brazilian migration to the United States. Ana Cristina Martes, a professor of sociology at Fundação Getúlio Vargas Brazil, helped explain the first few migratory trips to the U.S. which took place in Boston. She noticed a series of six events that could have led the cycle of migration:

- During World War II, American engineers from the Boston area travelled to Governador Valadares [a city in Minas Gerais, Brazil] …to work on the region’s mineral extraction and railroad…When they came back to the States, many of them brought their Brazilian domestic employees.

- After the war, some Bostonians strengthen the relationship with Valadares [by coming back on more trips for more precious stones].

- In the 1960s, newspapers from Rio [De Janeiro] and Sao Paulo published a number of ads offering jobs to Brazilian women interested in working as maids in Boston.

- [During the same time period, a business man from Massachusetts] hired twenty soccer players from Belo Horizonte to form a soccer team. Many of them stayed permanently and helped their family join them in the States.

- At the end of the decade, a group of more than ten young people from Governador Valadares decided to come to the States to spend more time on ‘an adventurous trip…in a country of their dreams’. They also settled permanently and helped their families join them.

- …several Brazilians came to study in Boston and decided not to return to Brazil.[14]

Before the 1960s there was insignificant movement from Brazil to the United States. It was between the 1960s through 1980s that some Brazilians went to the United States as tourists to visit places such as Disney World, New York and other tourist destinations. Brazilians travelled during that time because the country was growing at an average 7% annually and projecting 4% annual increase in GDP per capita.[15] After the 1980s, the peak of the economic cycle quickly dropped to a long lasting through. The Brazilian Federal Police reported that in the 1980s about 1.25 million people (1% of the population) emigrated to countries such as the U.S. This was the first time Brazilians emigrated in significant numbers. They wanted to stay in the States until the crisis was over. They also had some work connections and known opportunities in the East Coast, which increased facilitated the move. In 1980, there were 41,000 Brazilians and 82,000 by 1990. Neoclassical Economics Theory explains the beginning flow of migration in 1980 indicating that individuals were rational actors who looked for better opportunities away from home to improve his/her lifestyle. Since the crisis hit the Brazilian middle class hard, many chose to leave to optimize their income, find better jobs, and more stable social conditions by doing marginal benefit analysis.[16]

There was another wave of emigration in 2002 where Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs estimated that 1.96 million Brazilians had left again as the country continued to lack economic stability.[14] This number reflected another 1% of the Brazilian population 22 years later (“Population, total”). This wave of migration was different from the one in the 1980s. As shown by Martes’ research, migration evolved even more with a creation and better establishment of social networks. When Bostonians first brought back a wave of Brazilian domestic workers, Brazilians would send information to their homes about their experiences and opportunities. This connection is what Douglas Massey defined as Social Capital Theory. Migrants create social ties in the host country facilitating the move at lower cost and creating an incentive to join their community in another country.[17] Legal migrants who had entered the U.S. brought their immediate relatives resulting in an increase of the Brazilian immigrant population.

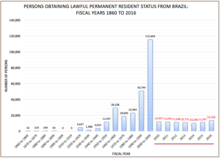

Lawful Permanent Resident Status

Brazilians obtained the highest number of lawful permanent residence status between 2000 and 2009 and many were eligible to naturalize. During that time, 115,404 Brazilians received permanent status and from 2010 through 2016, already 80,741 persons had received theirs. Still, it seems as if many received status, but if you compare to the total foreign born Brazilian population, the numbers are small. In 2010 the Brazilian foreign born population was 340,000 and only 12,057 (or 4% of) persons obtained legal status. Of the 336,000 foreign born Brazilians in 2014, only 10,246 (or 3%) received permanent status in the same year.[18] Even though few people are obtaining permanent status, there was a noticeable spike previously mentioned between 2000-2009. The increase in acceptance was due to two main factors: the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act and economic and political turmoil in Brazil.[19]

The top three classes of admissions for Brazilians obtaining lawful permanent status in the U.S. in 2016 was family-sponsored, employment, and immediate relatives of U.S. citizens. Each category of admissions makes up of 4%, 25%, and 68% respectively of the total individuals.[18]

Socioeconomics

Education

The 2000 U.S. Census showed that 34.5 percent of Brazilians had completed four or more years of college,[20] while the corresponding number for the general U.S. population is only 24.4 percent.[21] However, although effectively many Brazilian immigrants in the United States are university educated, most of these immigrants fail to get well-qualified jobs and have to get lower-status jobs because the United States doesn't recognize their qualifications and also because many of them do not speak English.[13]

Second-and third-generation Brazilian Americans tend to have better jobs; they have been educated in the United States, speak English, and have citizenship.[13]

Culture

Religion

Although the majority of Brazilian Americans are Roman Catholic, there also significant numbers of Protestants, Mormons,[22] Brazilian Catholics not in communion with Rome, Orthodox, Irreligious people (including atheists and agnostics), followed by minorities such as Spiritists, Buddhists, Jews and Muslims.

As with wider Brazilian culture, there is set of beliefs related through syncretism that might be described as part of a Spiritualism–Animism continuum, that includes: Spiritism (or Kardecism, a form of spiritualism that originated in France, often confused with other beliefs also called espiritismo, distinguished from them by the term espiritismo [de] mesa branca), Umbanda (a syncretic religion mixing African animist beliefs and rituals with Catholicism, Spiritism, and indigenous lore), Candomblé (a syncretic religion that originated in the Brazilian state of Bahia and that combines African animist beliefs with elements of Catholicism),[13] and Santo Daime (created in the state of Acre in the 1930s by Mestre Irineu (also known as Raimundo Irineu Serra) it is a syncretic mix of Folk Catholicism, Kardecist Spiritism, Afro-Brazilian religions and a more recent incorporation of Indigenous American practices and rites). People who profess Spiritism make up 1.3% of the country's population, and those professing Afro-Brazilian religions make up 0.3% of the country's population.

Demographics

Brazilians began immigrating to the United States in large and increasing numbers in the 1980s as a result of worsening economic conditions in Brazil at that time.[20] However, many of the Brazilians who have emigrated to the United States since this decade have been undocumented.[13] More women have immigrated to the United States from Brazil than men, with the 1990 and 2000 U.S. Censuses showing there to be ten percent more female than male Brazilian Americans. The top three metropolitan areas by Brazilian population are New York City (72,635),[2] Boston (63,930),[3] and Miami (43,930).[23]

Racial stereotype and Representation in the media

Like ethnic terms Hispanic and Latino, in popular use, Brazilian is often mistakenly given racial values, usually non-white and mixed race, such as half-caste or mulatto, in spite of the racial diversity of Brazilian Americans. Brazilians commonly draw ancestry from European, Indigenous populations, and African populations in different proportions; many Brazilians are largely of European ancestry, and some are predominantly of Native Brazilian Indian origin, or African origins, but a large number of Brazilians are descended from an admixture of two, three or more origins. Paradoxically, it is common for them to be stereotyped as being exclusively non-white due merely to their Latin background of country of origin, regardless of whether their ancestry is European or not. On the other hand, the white Brazilian Americans who are perceived by Americans as "Brazilian" usually possess typical Mediterranean/Southern European pigmentation - olive skin, dark hair, and dark eyes - as most white Brazilian immigrants are and most white Brazilian Americans are; the same situation happens for Portuguese Americans who are perceived by Americans as such, as most Portuguese immigrants are. Because Americans associate Brazilian origin with brown skin, Hollywood typically casts Brazilian Americans with conventionally Mediterranean features as non-Brazilian white.

Brazilian American communities

- New York City is a leading point of entry for Brazilians entering the United States.[24] West 46th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues in Manhattan has been designated Little Brazil has historically been a commercial center for Brazilians living in or visiting New York City.[25][26] Another NYC neighborhood home to many Brazilian Americans is located in Astoria, Queens.[27] Newark, New Jersey is also home to many Brazilian and Portuguese-Americans, most prominently in the city's Ironbound district.

- Massachusetts, particularly the Boston metropolitan area,[3] has a sizable Brazilian immigrant population. Framingham has the highest percentage of Brazilians of any municipality in Massachusetts.[28] Somerville has the highest number of Brazilians of any municipality in Massachusetts. Large populations also exist in Everett, Barnstable, Lowell, Marlboro, Malden, Shrewsbury, Worcester, Milford, Fitchburg, Leominster, Falmouth, Hudson, Revere, Edgartown, Lancaster, Dennisport, Chelsea, Lawrence, Vineyard Haven, Oak Bluffs, Millbury, and Leicester.

- South Florida's large Brazilian community is mostly centered around the islands and northeastern section of Miami-Dade County (North Bay Village, Bay Harbor Islands, Miami Beach, Surfside, Key Biscayne, Aventura, and Sunny Isles Beach) with the exception of Doral. In Broward County, the population is centered on the northeastern part as well (Deerfield Beach, Pompano Beach, Oakland Park, Coconut Creek, Lighthouse Point, and Sea Ranch Lakes), with some living on the border of Palm Beach County.[29][30]

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania has a vibrant Brazilian community, mostly settling in the Northeast section of the city, in communities such as Oxford Circle, Summerdale, Frankford, Juniata Park, Lawndale, Fox Chase, and Rhawnhurst. Many of the Brazilian residents started to come to Philadelphia during the early 2000s, opening restaurants, boutiques, supermarkets, and other stores along Bustleton, Castor, and Cottman Avenues. There's also smaller, but highly concentrated Brazilian communities such as Riverside, Delran, Cinnaminson, Palmyra, Delanco, Beverly, Edgewater Park, and Burlington.

- Los Angeles, California's Brazilian residents have tended to settle, if not form distinct ethnic enclaves in, the county's southern beach cities (Venice, Los Angeles; and suburbs of Lawndale; Long Beach; Manhattan Beach; and Redondo Beach) and Westside neighborhoods near and south of the 10 (Palms, Los Angeles; Rancho Park, Los Angeles; and West Los Angeles; and the suburb of Culver City). The city's greatest concentration of Brazilian American businesses began appearing in the late 1980s along Venice Boulevard's north border between Culver City and Palms (between Overland Avenue and Sepulveda Avenue).[31][32]

- Chicago, Illinois' Brazilian population began with the migration of Portuguese Sephardi Jews who had fled to Brazil during the World War II era. After World War II, many Sephardim successfully circumvented restrictive U.S. immigration laws, to join the large and largely Ashkenazi population in the Chicago area. However, it was not until the 1970s, did a visible Brazilian community begin to develop in Chicago. The Flyers Soccer Club was founded by a group of young men who desired to bring Brazilian soccer culture to the Chicago area. The Flyers Soccer Club eventually transformed into a multifaceted community organization called the Luso-Brazilian Club. The group was headquartered in Chicago's Lakeview neighborhood. The group declined in the late 1980s. As Brazilians emigrated to the United States in large numbers in the 1980s and 1990s, Chicago's Brazilian population remained comparatively small, numbering no more than several thousand people by 2000.[33] The FIFA World Cups have attracted the attention of Chicago's Brazilian population through the years, leading to the development of some Brazilian soccer-interested gatherings in the area.[34]

U.S. communities with high percentages of people of Brazilian ancestry

According to ePodunk, a website, the top 50 U.S. communities with the highest percentages of people claiming Brazilian ancestry are:[35]

- North Bay Village, Florida 6.00%

- Riverside, New Jersey 5.00%

- Danbury, Connecticut 4.90%

- Harrison, New Jersey 4.80%

- Framingham, Massachusetts 4.80%

- Somerville, Massachusetts 4.50%

- Kearny, New Jersey 3.70%

- Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts 3.60%

- Deerfield Beach, Florida 3.50%

- Everett, Massachusetts 3.20%

- Marlborough, Massachusetts 3.10%

- Long Branch, New Jersey 2.80%

- Edgartown, Massachusetts 2.70%

- Newark, New Jersey 2.50%

- Doral, Florida 2.50%

- Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts 2.50%

- Miami Beach, Florida 2.20%

- Hillside, New Jersey 2.20%

- Hudson, Massachusetts 2.20%

- Oakland Park, Florida 2.10%

- South River, New Jersey 2.10%

- Cliffside Park, New Jersey2.10%

- Tisbury, Massachusetts 2.10%

- Fairview, New Jersey 2.00%

- Aventura, Florida 1.90%

- Lauramie, Indiana 1.80%

- Revere, Massachusetts 1.70%

- Malden, Massachusetts 1.70%

- Sea Ranch Lakes, Florida 1.70%

- Surfside, Florida 1.60%

- Barnstable, Massachusetts 1.60%

- Lowell, Massachusetts 1.60%

- Ojus, Florida 1.60%

- Washington, Ohio 1.60%

- Naugatuck, Connecticut 1.60%

- Milford, Massachusetts 1.50%

- Dennis Port, Massachusetts 1.50%

- Keene, Texas 1.50%

- Key Biscayne, Florida 1.50%

- Mount Vernon, New York 1.50%

- Avondale Estates, Georgia 1.50%

- Sunny Isles Beach, Florida 1.50%

- Riverside, New Jersey 1.40%

- Trenton, Florida 1.40%

- South Lancaster, Massachusetts 1.30%

- Great River, New York 1.30%

- Port Chester, New York 1.30%

- Coconut Creek, Florida 1.20%

- Belle Isle, Florida 1.20%

- Big Pine Key, Florida 1.20%

- Chelsea, Massachusetts 1.20%

U.S. communities with the most residents born in Brazil

According to the social networking and information website City-Data, the top 25 U.S. communities with the highest percentage of residents born in Brazil are:[36]

- Loch Lomond, Florida 15.8%

- Bonnie Loch-Woodsetter North, Florida 7.2%

- North Bay Village, Florida 7.1%

- East Newark, New Jersey 6.7%

- Framingham, Massachusetts 6.6%

- Harrison, New Jersey 5.8%

- Danbury, Connecticut 5.6%

- Somerville, Massachusetts 5.4%

- Sunshine Ranches, Florida 5.1%

- Flying Hills, Pennsylvania 5.1%

- Deerfield Beach, Florida 4.7%

- Fox River, Alaska 4.5%

- Edgartown, Massachusetts 4.4%

- West Yarmouth, Massachusetts 4.4%

- Marlborough, Massachusetts 4.4%

- Kearny, New Jersey 4.4%

- Doral, Florida 4.1%

- Everett, Massachusetts 4.0%

- Long Branch, New Jersey 3.7%

- Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts 3.4%

- Hudson, Massachusetts 3.2%

- Miami Beach, Florida 3.1%

- Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts 3.0%

- Oakland Park, Florida 3.0%

- Pompano Beach Highlands, Florida 3.0%

Some City-Data information contradicts official government data from the Census Bureau. It is important to be mindful that Brazilian Americans sometimes decline to identify as Latino. Therefore, the above estimates may outnumber the Census data figures for Hispanics and/or Latinos for the above Census areas.

Relations with Brazil

Voting Brazilian Americans and Brazilians abroad heavily favored the opposition's Aecio Neves and his pro-business centre to centre-right Brazilian Social Democracy Party in Brazil's 2014 general election.[37][38] Aecio Neves and the Brazilian Social Democracy Party, or PSDB, were narrowly defeated in the 2014 runoff.[39]

Brazilian Americans represent a large source of remittances to Brazil. Brazil receives approximately one quarter of its remittances from the U.S. (26% in 2012), out of a total amount of $4.9 billion received in 2012.[40][41]

Notable people

Arts

- Gustavo Assis-Brasil, musician, composer, author

- Morena Baccarin, actress

- Camilla Belle, actress[42][43]

- Blondfire, pop music band

- Jordana Brewster, actress

- Bruno Campos, actor

- Max Cavalera, musician

- Mônica da Silva, singer, songwriter

- Sky Ferreira, singer, songwriter, model, and actress

- Bebel Gilberto, singer

- Jared Gomes, rapper and vocalist from Hed PE

- Bill Handel, radio personality

- Rudy Mancuso, comedian and Internet personality

- Camila Mendes, actress

- Fabrizio Moretti, musician

- Naza, visual artist

- Carlinhos Pandeiro de Ouro, Percussionist

- Linda Perry, musical producer and songwriter

- Joe Penna, writer and director

- Nancy Randall, model

- Carlos Saldanha, film director and animator

- Maiara Walsh, actress

- Julia Goldani Telles, actress

Sports

- Bob Burnquist, professional skateboarder[44][45]

- Gil de Ferran, race car driver and team owner

- Benny Feilhaber, soccer player

- Nenê Hilário, basketball player

- Ryan Hollweg, hockey player

- Louise Lieberman (born 1977), soccer coach and former player

- Douglas Lima, mixed martial artist

- Dhiego Lima, mixed martial artist

- Sergio Menezes, footvolley athlete and founder of pro tour

- Amen Santo, Capoeira Master.

- Cairo Santos, Kansas City Chiefs placekicker.

- Vic Seixas (born 1923), Hall of Fame former top-10 tennis player

- José Leonardo Ribeiro da Silva, Soccer Player

- Wanderlei Silva, Mixed Martial Artist [46]

- Anderson Silva, Mixed Martial Artist [47]

- Scott Machado, basketball player

- Isadora Williams, figure skater[48]

- Yan Gomes, baseball player

- Rafael Araujo-Lopes, American Football Player

Academics

- Ana Maria Carvalho, PhD., professor of Linguistics at the Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of Arizona[49][50]

- Lin Chao, PhD., professor of Ecology at the University of California, San Diego[51]

- Flavia Colgan, political strategist

- Marcelo Gleiser, PhD., physicist and astronomer. Appleton Professor of Natural Philosophy and Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Dartmouth College[52][53]

- Ben Goertzel, PhD., former professor of Computer Sciences at the University of New Mexico, researcher of artificial intelligence, visiting faculty at Xiamen University[54]

- Miguel Nicolelis, M.D., Ph.D., Duke School of Medicine Distinguished Professor of Neuroscience, Duke University Professor of Neurobiology, Biomedical Engineering and Psychology and Neuroscience, and founder of Duke's Center for Neuroengineering.[55][56][57]

- Roberto Mangabeira Unger, LL.M., S.J.D., Roscoe Pound Professor of Law at the Harvard Law School (Harvard University)[58]

Business

- David Neeleman, businessman, founder of JetBlue and Azul Brazilian Airlines[59]

- Eduardo Saverin, Facebook co-founder; renounced his U.S. citizenship in 2011

See also

- American Brazilians

- Portuguese Americans

- Brazilian Day - Brazilian American party of New York

- List of Brazilian Americans

- Brazilian British

References

- US Census Bureau 2012 American Community Survey B040003 TOTAL ANCESTRY REPORTED Universe: Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "SELECTED POPULATION PROFILE IN THE UNITED STATES 2012 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- "SELECTED POPULATION PROFILE IN THE UNITED STATES 2012 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- Alphine W. Jefferson, "Brazilian Americans." in Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 1, Gale, 2014), pp. 343-355. online

- "Brazilian Immigrant Women in the Boston area: Negotiation of Gender, Race, Ethnicity, Class and Nation". Archived from the original on 2010-01-28.

- "Imigrante brasileiro espera anistia de sucessor de Bush - 01/11/2008 - UOL Eleição americana 2008". noticias.uol.com.br. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- Office of Management and Budget. "Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Federal Register Notice October 30, 1997". Retrieved 2008-01-11.

- United States Census Bureau (March 2001). "Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- "B03001. Hispanic or Latino Origin by Spedific Origin". 2006 American Community Survey. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- "49 CFR Part 26". U.S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

'Hispanic Americans,' which includes persons of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Dominican, Central or South American, or other Spanish or Portuguese culture or origin, regardless of race;

- "US Small Business Administration 8(a) Program Standard Operating Procedure" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-25. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

SBA has defined 'Hispanic American' as an individual whose ancestry and culture are rooted in South America, Central America, Mexico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, or the Iberian Peninsula, including Spain and Portugal.

- Alphine W. Jefferson. "A Countries and Their Cultures: Brazilian Americans". Countries and their cultures. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- Jouët-Pastré, Clémence, and Leticia J. Braga (2008). Becoming Brazuca: Brazilian immigration to the United States. Harvard University David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Goza, Franklin (1994). "Brazilian Immigration to North America". The International Migration Review. 28 (1): 136–152. doi:10.2307/2547029. JSTOR 2547029.

- UN Human Development Report, 2009, Chapter 2, sections 2.1 and 2.2

- Massey, Douglas S. 1999. “Why Does Immigration Occur? A Theoretical Synthesis." Pp. 34-52 in The Handbook of International Migration: The American Experience, edited by C. Hirschman, P. Kasinitz and J. DeWind. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- "Yearbook 2016". Department of Homeland Security. 2017-05-16. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- "Naturalization Trends in the United States". migrationpolicy.org. 2016-08-09. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- Franklin Goza, Bowling Green State University. "An Overview of Brazilian Life as Portrayed by the 2000 U.S. Census" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-08-01. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- U.S. Census Bureau. "Educational Attainment: 2000" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- "Brazil - LDS Statistics and Church Facts - Total Church Membership". mormonnewsroom.org. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "SELECTED POPULATION PROFILE IN THE UNITED STATES 2011-2013 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- "Brazilians are taking New York City by storm — with their cash". pri.org. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- Walter Godinez (December 9, 2014). "The World in NYC: Brazil". New York International.

- Cortés, C.E. (2013). Multicultural America: A Multimedia Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 391. ISBN 9781452276267. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Little Brazil (New York City, USA)". zonalatina.com. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-12-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Philippe Dionne. "Community Focus: Brazilians in South East Florida". culturemapped.com. Archived from the original on 2017-03-06. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Brazilian community in South Florida lures investment from companies in Brazil - tribunedigital-sunsentinel". articles.sun-sentinel.com. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Brazilian enclave takes root in Culver City, boosted by World Cup - LA Times". latimes.com. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- Ochoa, E.; Ochoa, G.L. (2005). Latino Los Angeles: Transformations, Communities, and Activism. University of Arizona Press. p. 179. ISBN 9780816524686. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Brazilians". encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-02-19. Retrieved 2016-02-16.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Ancestry Map of Brazilian Communities". Epodunk.com. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- "Top 101 cities with the most residents born in Brazil (population 500+)". city-data.com. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- Margheritis, A. (2015). Migration Governance Across Regions: State-Diaspora Relations in the Latin America-Southern Europe Corridor. Taylor & Francis. p. 128. ISBN 9781317437864. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Brazilian voter turnout abroad up 63% - Agência Brasil". agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Subscribe to read". on.ft.com. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "3. Sources of Remittances to Latin America - Pew Research Center". pewhispanic.org. 2013-11-14. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-24. Retrieved 2016-02-16.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "GQ: Cool New Stuff - Films, Gadgets, Motors, Girls, Bars, Fashion, Grooming". Archived from the original on 2006-06-23. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "The Daily Princetonian - Belle of the ball". Archived from the original on 2008-01-03. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- Ruibal, Sal (2008-06-18). "Skateboarder Burnquist strikes a balance on Dew Tour - USATODAY.com". USA Today. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- Thomas, Pete (4 August 2006). "Event No Longer Simply Child's Play". Articles.latimes.com. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- "Wanderlei Silva -- I'M AN AMERICAN CITIZEN NOW ... And I'm Gonna Save Brazil!! (VIDEO)". Tmz.com. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- "Anderson Silva grateful to be sworn in as U.S. citizen: 'This is my country now'". mmajunkie.com. July 24, 2019.

- Good Luck on Your Olympic Journey, Isadora Williams

- "Ana Maria Carvalho | Ana Maria Carvalho". anacarvalho.faculty.arizona.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Ana Maria Carvalho - Center for Latin American Studies". las.arizona.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Lin Chao". biology.ucsd.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Marcelo Gleiser - Department of Physics and Astronomy". Physics.dartmouth.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Marcelo Gleiser". Dartmouth.edu. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- "Biography". goertzel.org. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Miguel A Nicolelis - Duke Biomedical Engineering". bme.duke.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Nicolelis Lab - Duke Neurobiology". Neuro.duke.edu. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- "Miguel Nicolelis - Duke Institute for Brain Sciences - Brain Functions Research & Science". dibs.duke.edu. Archived from the original on 2019-02-01. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- Harvard Law School. "Roberto Mangabeira Unger - Harvard Law School". hls.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- Horch, Dan. "Azul, Brazil Airline Started by JetBlue Founder, Files for I.P.O." Dealbook.nytimes.com. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

Further reading

- Jefferson, Alphine W. "Brazilian Americans." in Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 1, Gale, 2014), pp. 343–355. online

- Jouët-Pastré, Clémence, and Leticia J. Braga. Becoming Brazuca: Brazilian Immigration to the United States (Harvard University David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, 2008).

- Margolis, Maxine L. Little Brazil: An Ethnography of Brazilian Immigrants in New York City (1994).

- Piscitelli, Adriana. “Looking for New Worlds: Brazilian Women as International Migrants.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 33#4 (2008): 784–93.