Pacific Islander Americans

Pacific Islander Americans (also known as Oceanian Americans) are Americans who are of Pacific Islander ancestry (or are descendants of the indigenous peoples of Oceania). For its purposes, the United States Census also counts Indigenous Australians as part of this group.[2][3]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 582,718 alone 0.2% of the total U.S. population (2018)[1] 1,225,195 alone or in combination 0.4% of the total U.S. population (2010 Census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, California, Hawaii, Washington, Oregon, Nevada, New York, Texas, Florida | |

| Languages | |

| American English, Polynesian languages, Micronesian languages | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Polytheism, Bahá'í, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Sikhism, Jainism, Confucianism, Druze | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pacific Islanders |

Pacific Islander Americans make up 0.5% of the U.S. population including those with partial Pacific Islander ancestry, enumerating about 1.4 million people. The largest ethnic subgroups of Pacific Islander Americans are Native Hawaiians, Samoans, Chamorros, Fijians, Palauans and Tongans.

American Samoa, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands are insular areas (U.S. territories), while Hawaii is a state.

History

First stage: Hawaiian migration (18th-19th centuries)

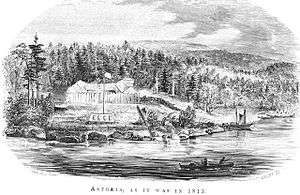

Migration from Oceania to the United States began in the last decade of the eighteenth century, but the first migrants to arrive in this country were natives of Hawaii. People from other Oceanian backgrounds (except Australians and New Zealanders) did not migrate to the United States until late nineteenth century. The first native Hawaiians to live in the United States were fur traders. They were hired by British fur traders in Hawaii and taken to the northwestern United States, from where developed trade networks with Honolulu. However, they charged less than Americans for doing the same jobs and returned to Hawaii when their contracts ended. The first Native Hawaiians to live permanently in the United States settled in the Astoria Colony (in the present-day Oregon) in 1811, having been brought there by its founder, fur merchant John Jacob Astor. Astor created the Pacific Fur Company in the colony and used the native Hawaiians to build the city's infrastructure and houses and to work in the primary sector (agriculture, hunting and fishing) to make them serve the company (although later, most of them worked for North West Company when this company absorbed the Pacific Fur Company in 1813).

After 1813, Native Hawaiians continued to migrate to the Pacific Northwest to work for other companies, such as the Hudson Bay Company (which absorbed the North West Company in 1821) and the Columbia Fishing and Trading Company, as well as in Christian missions.[4] Since 1819 some groups of Polynesian Protestant students immigrated to the United States to study theology.[5] Since the 1830s, another groups of Native Hawaiians arrived on California's shores,[5][4] where they were traders and formed great communities (they made up 10 percent of the population of Yerba Buena, now San Francisco, in 1847). During the California Gold Rush, many other native Hawaiians migrated to California to work as miners.[4]

In 1889, the first Polynesian Mormon colony was founded in Utah and consisted of Hawaiian natives, Tahitians, Samoans and Maori people.[5] Also in the late nineteenth century small groups of Pacific Islanders, usually sailors, moved to the western shores, mainly on San Francisco.[6] Later, the U.S. occupied Hawaii in 1896, Guam in 1898 and American Samoa in 1900.[7] This fact diversified Oceanian emigration in the United States.

Second stage (20th-21st centuries)

However, the first record of non-Hawaiian Pacific Islanders in the United States is from 1910,[4] with the first Guamanians living in the United States. In the following decades small groups of people from islands such as Hawaii, Guam,[6] Tonga or American Samoa emigrated to the United States, but many of them were Mormons (including most of Tongans and American Samoans),[8][9] who emigrated to help build Mormon churches,[8] or look for an education, either in Laie[9] or Salt Lake City.[10] However, the emigration of Pacific Islanders to the U.S. was small until the end of World War II,[4] when many American Samoans,[11] Guamanians (who got the American citizenship in 1929[9]) and Tongans emigrated to the USA. Most of them were in the military or married with military people[6] (except Tongans, who looked for a job in several religious and cultural centers). Since then the emigration increased and diversified every decade, with a majority emigrating to the Western urban areas and Hawaii.[4]

This increase and diversification in the Oceanian emigration was especially true in the 1950s. In 1950, the population of Guam gained full American citizenship,[8] and in 1952 the natives of American Samoa become U.S. nationals, although not American citizens, through the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952.[12] Shortly thereafter, the first major migration waves from American Samoa[13][11] and Guam[14] emerged, while other groups of places such as French Polynesia, Palau or Fiji began to emigrate. Over 5,100 Pacific Islander emigrated to the United States in the 1950s, mostly from American Samoa (although the first of them were military personnel[15]), Guam, and Tonga. Most of them were Mormons[16] and many Pacific Islanders emigrated to the United States seeking economic opportunities.

In 1959, Hawaii became a U.S. state, which dramatically strengthened the indigenous population of Oceania in the US.[17] In the 1960s many more Pacific Islanders emigrated to the US, especially due to increased migration from Guam (whose natives were fleeing the Korean War and the Typhoon Karen),[18] Fiji (whose migration increased dramatically, as the Fijians who emigrated to the USA went from being a few dozen in the 50s to over 400 people), Tonga[10][19] and Samoa archipelago (including independent Samoa[9]).[20] This migration increased especially since 1965,[10][9][19] when the U.S. government facilitated the non-European migration to the USA.[10] Many of them were recruited to pick fruit in California.[18]

During the 1970s, over nine thousand Pacific Islanders migrated to the US, mostly from Samoa[13] (both Western and American[21]), Guam, Tonga and Fiji, but also from other islands such as Federated States of Micronesia or Palau. Many of these people emigrated to the U.S. to study at its universities.[22] In addition, in the 1980s (specifically in 1986), migration from the Pacific Islands to the United States become more diversified when this country acquired the Northern Marianas Islands[23] and created an agreement with the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (FSM, Palau and the Marshall Islands) called the Compact of Free Association, which allows its inhabitants to travel and work in the United States without visas.[note 1] The Tyson Foods company (which employed a significant part of the population of the Marshall Islands) relocated many of its Marshellese employees in Springdale, Arkansas, where the company is based.[24] However, most of Pacific Islanders continued to migrate to western urban areas and Hawaii.[4] More of five thousand Pacific Islanders migrated to the United States in the 90's, settling mostly in western cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, or Salt Lake City.[4] In the 2000 census almost all the origins of Oceania were mentioned, although only the ethnic groups mentioned in the article consisted of thousands of people.[25] In the 2000s and 2010s several thousands more Pacific Islanders emigrated to the USA.

Population

Demography

In the 2000 and 2010 U.S. Census, the term "Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander" refers to people having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Tonga, Samoa, Fiji, New Zealand and the Marshalls or other Pacific Islands. Most of the Pacific Islander Americans are of Native Hawaiian, Samoan and Chamorro origin.

The fact that Hawaii is a U.S. state (meaning that almost the entire native Hawaiian population lives in the U.S.), as well as the migration, high birth rate and miscegenation of the Pacific Islanders have favoured the permanence and increase of this population in the U.S. (especially in the number of people who are of partial Pacific Islander descent). In the 2000 census, over 800,000 people claimed be of Pacific Islander descent and already in the 2010 census 1,225,195 Americans claimed "'Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander'" as their race alone or in combination. Most of them live in urban areas of Hawaii and California, but they also have sizeable populations in Washington, Utah, Nevada, Oregon, Texas, Florida, Arizona and New York. On the other hand, Pacific Islander Americans are majority (or are the main ethnic group) in American Samoa, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands, from where many of them are natives.

Pacific Islander Americans in the 2000[25]–2010 U.S. Census[26] (From over 1,000 people)

| Ancestry | 2000 | 2000 % of Pacific Islander American population | 2010 | 2010 % of Pacific Islander American population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fijian | 13,581 | 1.6% | 32,304 | 2.6% |

| French Polynesian | 3,313 | 0.4% | 5,062 | 0.4% |

| Marshallese | 6,650 | 0.8% | 22,434 | 1.8% |

| "Micronesian" (not specified) | 9,940 | 1.1% | 29,112 | 2.4% |

| Micronesian (FSM) | 1,948 | 0.2% | 8,185 | 0.7% |

| Polynesians with New Zealand citizenship (Māori, Tokelauans, Niueans, Cook Islanders) | 2,422 (Māori: 1,994; Tokelauans: 574) | 0.3% | 925 (Tokelauans only) | 0.1% |

| Chamorro | 93,237 (Guamanian or Chamorro: 92,611; Saipanese: 475; Mariana Islander: 141) | 10.7% | 148,220 (Guamanian or Chamorro: 147,798; Saipanese: 1,031; Mariana Islander: 391) | 12.2% |

| Native Hawaiians | 401,162 | 45.9% | 527,077 | 43.0% |

| Palauan | 3,469 | 0.4% | 7,450 | 0.6% |

| "Polynesian" (not specified) | 8,796 | 1.0% | 9,153 | 0.7% |

| Samoan | 133,281 | 15.2% | 184,440 | 15.1% |

| Tongan | 36,840 | 4.2% | 57,183 | 4.7% |

| Others | 188,389 | % | 241,952 | % |

| TOTAL | 874,414 | 100.0% | 1,225,195 | 100.0% |

Location

| State/territory | Pacific Islander Americans alone (2010 U.S. Census)[27] | Pacific Islander Americans alone or in combination (2010 U.S. Census)[28] | Percentage (Pacific Islander Americans alone)[note 2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 5,208 | 7,984 | 0.1% |

| Alaska | 7,662 | 11,360 | 1.0% |

| American Samoa | 51,403[29] | 52,790[30] | 92.6%[31] |

| Arizona | 16,112 | 28,431 | 0.2% |

| Arkansas | 6,685 | 8,597 | 0.2% |

| California | 181,431 | 320,036 | 0.8% |

| Colorado | 8,420 | 16,823 | 0.1% |

| Connecticut | 3,491 | 6,864 | 0.0% |

| Delaware | 690 | 1,423 | 0.0% |

| District of Columbia | 770 | 1,514 | - |

| Florida | 18,790 | 43,416 | - |

| Georgia | 10,454 | 18,587 | 0.1% |

| Guam | 78,582 [32] | 90,238 [33] | 49.3%[34] |

| Hawaii | 138,292 | 358,951 | 10.0% |

| Idaho | 2,786 | 5,508 | 0.1% |

| Illinois | 7,436 | 15,873 | - |

| Indiana | 3,532 | 7,392 | 0.1% |

| Iowa | 2,419 | 4,173 | 0.1% |

| Kansas | 2,864 | 5,445 | 0.1% |

| Kentucky | 3,199 | 5,698 | 0.1% |

| Louisiana | 2,588 | 5,333 | - |

| Maine | 377 | 1,008 | - |

| Maryland | 5,391 | 11,553 | - |

| Massachusetts | 5,971 | 12,369 | - |

| Michigan | 3,442 | 10,010 | <0.1% |

| Minnesota | 2,958 | 6,819 | 0.0% |

| Mississippi | 1,700 | 3,228 | - |

| Missouri | 7,178 | 12,136 | 0.1% |

| Montana | 734 | 1,794 | 0.1% |

| Nebraska | 2,061 | 3,551 | 0.1% |

| Nevada | 19,307 | 35,435 | 0.6% |

| New Hampshire | 532 | 1,236 | - |

| New Jersey | 7,731 | 15,777 | - |

| New Mexico | 3,132 | 5,750 | 0.1% |

| New York | 24,000 | 45,801 | 0.1% |

| North Carolina | 10,309 | 17,891 | 0.1% |

| North Dakota | 334 | 801 | 0.1% |

| Northern Mariana Islands | 18,800 [35] | 24,891 [36] | 34.9%[37] |

| Ohio | 5,336 | 11,380 | 0.03% |

| Oklahoma | 5,354 | 9,052 | 0.1% |

| Oregon | 14,649 | 26,936 | 0.4% |

| Pennsylvania | 7,115 | 14,662 | - |

| Puerto Rico | 370 [38][39] | 555[40] | 0.0% |

| Rhode Island | 1,602 | 2,803 | 0.1% |

| South Carolina | 3,957 | 6,988 | 0.1% |

| South Dakota | 517 | 1,040 | 0.1% |

| Tennessee | 5,426 | 9,359 | 0.1% |

| Texas | 31,242 | 54,801 | 0.1% |

| Utah | 26,049 | 37,994 | 1.3% |

| Vermont | 175 | 476 | - |

| Virgin Islands (U.S.) | 16 [41] | 212[42] | 0.0% |

| Virginia | 8,201 | 17,233 | 0.1% |

| Washington | 43,505 | 73,213 | 0.6% |

| West Virginia | 485 | 1,295 | - |

| Wisconsin | 2,505 | 5,558 | - |

| Wyoming | 521 | 1,137 | 0.1% |

| United States | 674,625 | 1,332,494 | 0.2% |

Micronesian Americans

Micronesian Americans are Americans of Micronesian descent.

According to the 2010 census, the largest Chamorro populations were located in California, Washington and Texas, but their combined number from these three states totaled less than half the number living throughout the U.S. It also revealed that the Chamorro people are the most geographically dispersed Oceanic ethnicity in the country.[43]

Marshallese Americans or Marshallese come from the Marshall Islands. In the 2010 census, 22,434 Americans identified as being of Marshallese descent.

Because of the Marshall Islands entering the Compact of Free Association in 1986, Marshallese have been allowed to migrate and work in the United States. There are many reasons why Marshallese came to the United States. Some Marshallese came for educational opportunities, particularly for their children. Others sought work or better health care than what is available in the islands. Massive layoffs by the Marshallese government in 2000 led to a second big wave of immigration.

Arkansas has the largest Marshallese population with over 6,000 residents. Many live in Springdale, and the Marshallese comprise over 5% of the city's population. Other significant Marshallese populations include Spokane and Costa Mesa.

Polynesian Americans

Polynesian Americans are Americans of Polynesian descent.

Large subcategories of Polynesian Americans include Native Hawaiians and Samoan Americans. In addition there are smaller communities of Tongan Americans (see Culture and diaspora of Tonga), French Polynesian Americans, and Māori Americans.

A Samoan American is an American who is of ethnic Samoan descent from either the independent nation Samoa or the American territory of American Samoa. Samoan American is a subcategory of Polynesian American. About 55,000 people live on American Samoa, while the U.S. census in 2000 and 2008 has found 4 times the number of Samoan Americans live in the mainland USA.

California has the most Samoans; concentrations live in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles County, and San Diego County. San Francisco has approximately 2,000 people of Samoan ancestry, and other Bay Area cities such as East Palo Alto and Daly City have Samoan communities. In Los Angeles County, Long Beach and Carson have abundant Samoan communities, as well as in Oceanside in San Diego County.[44][45][46] Other West Coast metropolitan areas such as Seattle have strong Samoan communities, mainly in King County and in Tacoma. Anchorage, Alaska, and Honolulu, Hawaii, both have thousands of Samoan Americans residing in each city.

Persons born in American Samoa are United States nationals, but not United States citizens (this is the only circumstance under which an individual would be one and not the other).[12] For this reason, Samoans can move to Hawaii or the mainland United States and obtain citizenship comparatively easily. Like Hawaiian Americans, the Samoans arrived in the mainland in the 20th century as agricultural laborers and factory workers.

Elsewhere in the United States, Samoan Americans are plentiful throughout the state of Utah, as well as in Killeen, Texas; Norfolk, Virginia; and Independence, Missouri.

A Tongan American is an American who is of ethnic Tongan descent. Utah has the largest Tongan American population, followed by Hawaii. Many of the first Tongan Americans came to the United States in connection to the LDS Church.

Military

Based on 2003 recruiting data, Pacific Islander Americans were 249% over-represented in the military.[47]

American Samoans are distinguished among the wider Pacific Islander group for enthusiasm for enlistment. In 2007, a Chicago Tribune reporter covering the island's military service noted, "American Samoa is one of the few places in the nation where military recruiters not only meet their enlistment quotas but soundly exceed them."[48] As of March 23, 2009, there have been 10 American Samoans who have died in Iraq, and 2 who have died in Afghanistan.[49]

Pacific Islander Americans are also represented in the Navy SEALS, making up .6% of the enlisted and .1% of the officers.[50]

Notes

- The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands was a United Nations territory administrated by United States since 1944 until 1986/94 (depending on the country), although it didn't belong to him.

- Percentage of the state population that identifies itself as Pacific Islanders relative to the state/territory population as a whole — the percentage is of Pacific Islander Americans alone.

References

- "ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. December 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- University of Virginia. Geospatial and Statistical Data Center. "1990 PUMS Ancestry Codes." 2003. August 30, 2007."Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 25, 2007. Retrieved August 31, 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Clark Library - U-M Library". www.lib.umich.edu.

- Barkan, Elliott Robert (2013). Immigrants in American History: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration. Volume 4. ABC-Clio. ISBN 9781598842203. Chapter: Pacific Islander and Pacific Islander Americans, 1940-present, written by Matthew Kester.

- Brij V. Lal, Kate Fortune (2000). The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia, Volumen 1. University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 115–116.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Huping Ling, Allan W. Austin (2010). Asian American History and Culture: An Encyclopedia. Volume one-two. Routledge. p. 524.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- >"American Samoa Office of Insular Affairs". www.doi.gov. U.S. Department of the Interior. June 11, 2015.

- Pettey, Janice Gow (2002). Cultivating Diversity in Fundraising. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. p. 22. ISBN 9780471226017.

- Barkan, Elliott Robert (2013). Immigrants in American History: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration. Part 3. ABC-Clio. p. 1177. ISBN 9781598842197. Chapter: Pacific Islander and Pacific Islander Americans, 1940-present, written by Matthew Kester.

- Cathy A. Small, David L. Dixon (February 1, 2004). "Tonga: Migration and the Homeland". MPI: Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved May 24, 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Stantom, Max (1973). SAMOAN SAINTS SETTLERS AND SOJOURNERS. University of Oregon. pp. 21, 23. From work Samoan Saints: the Samoans in the mormon village of Laie, Hawaii.

- American Samoa and the Citizenship Clause: A Study in Insular Cases Revisionism. Chapter 3. Harvard Law Review. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Gordon R. Lewthwaite, Christiane Mainzer, and Patrick J. Holland (1973). "From Polynesia to California: Samoan Migration and Its Sequel". The Journal of Pacific History. The Journal of Pacific History. Vol. 8. 8: 25. doi:10.1080/00223347308572228. JSTOR 25168141.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- M. Flint Beal, Anthony E. Lang, Albert C. Ludolph (2005). Neurodegenerative Diseases: Neurobiology, Pathogenesis and Therapeutics. Cambridge. p. 835. ISBN 9781139443456.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Paul R. Spickard, Joanne L. Rondilla, Debbie Hippolite Wrigh (2002). "Pacific Diaspora: Island Peoples in the United States and Across the Pacific". University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 120–121.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Embry, Jessie L. (2001). Mormon Wards as Community. Global Publications, Binghamton University, New York. p. 124.

- "Commemorating 50 Years of Statehood". archive.lingle.hawaii.gov. State of Hawaii. March 18, 2009. Archived from the original on March 21, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- "Civil Rights Digest, Volumes 9-11". U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. 1974. p. 43. Chapter: Pacific Islanders in the U.S., written by Faye Untalan Muñoz.

- Danver, Steven L. (2013). "Encyclopedia of Politics of the American West". Sage Reference, Walden University. p. 515.

- Gershon, Ilana (2001). No Family Is an Island: Cultural Expertise among Samoans in Diaspora. Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London. p. 10.

- John Connell, ed. (1990). Migration and Development in the South Pacific. National Centre for Development Studies, The Australian National University. pp. 172–173.

- "Micronesians Abroad", Micronesian Counselor, published by Micronesian Seminar, authored by Francis X. Hezel and Eugenia Samuel, number 64, December 2006, retrieved 8 July 2013

- "Proclamation 5564—United States Relations With the Northern Mariana Islands, Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- Dan Craft (December 29, 2010). "Marshallese immigration". Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- The Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander Population, Census 2000

- The Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander Population: 2010 Census, 2010 Census Briefs, United States Bureau of the Census, May 2012

- US Census Bureau: " Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States, States, and Counties: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015" Archived February 14, 2020, at Archive.today retrieved September 05, 2016 - select state from drop-down menu

- US Census Bureau: " Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States, States, and Counties: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015" Archived February 14, 2020, at Archive.today retrieved September 05, 2016 - select state from drop-down menu

- Bureau, U. S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- Bureau, U. S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- Indexmundi.com. American Samoa. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- Bureau, U. S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- Bureau, U. S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- Indexmundi.com. Indexmundi: Guam Demographics Profile 2019. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- Bureau, U. S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- Bureau, U. S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- Indexmundi.com. Northern Mariana Islands. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- Archived October 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine American FactFinder. Race and Hispanic or Latino Origin: 2010. 2010 Census Summary File 1. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- Suburbanstats.org. Pacific Islanders in Puerto Rico. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- NATIVE HAWAIIAN AND OTHER PACIFIC ISLANDER ALONE OR IN COMBINATION WITH ONE OR MORE OTHER RACES (in Puerto Rico)

- Archived February 12, 2020, at Archive.today American FactFinder. Race (Total Population). 2010 U.S. Virgin Islands Summary File. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- RACE (TOTAL RACES TALLIED)

- "2010 Census Shows More than Half of Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders Report Multiple Races". United States Census 2010. United States government. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- Knight, Heather (March 1, 2006). "A YEAR AT MALCOLM X: Second Chance at Success Samoan families learn American culture". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- Sahagun, Louis (October 1, 2009). "Samoans in Carson hold church services for tsunami, earthquake victims". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- Garrison, Jessica. "Samoan Americans at a Crossroads", Los Angeles Times, April 14, 2000. Retrieved 2010-10-3.

- "Who Bears the Burden?". Heritage Foundation.

- Scharnberg, Kirsten (March 21, 2007). "Young Samoans have little choice but to enlist". Chicago Tribune.

- Congressman Faleomavaega (March 23, 2009). "WASHINGTON, D.C.—AMERICAN SAMOA DEATH RATE IN THE IRAQ WAR IS HIGHEST AMONG ALL STATES AND U.S. TERRITORIES". Press Release. United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on October 9, 2009. Retrieved September 30, 2009.

- "Navy SEALS to Diversify". Time. March 12, 2012.