Yaqui

The Yaqui or Hiaki or Yoeme are an Uto-Aztecan speaking indigenous people of Mexico who inhabit the valley of the Río Yaqui in the Mexican state of Sonora and the Southwestern United States. They also have communities in Chihuahua and Durango. The Pascua Yaqui Tribe is based in Tucson, Arizona. Yaqui people live elsewhere in the United States, especially California, Texas and Nevada.

Yaqui Indians | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 25,486 (2010 census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 14,162[1] | |

| 11,324 | |

| Languages | |

| Yaqui, English, Spanish | |

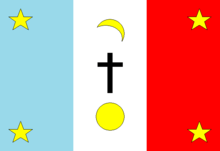

| Religion | |

| Indigenous Religion, Peyotism, Christianity, Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mayo Uto-Aztecan people | |

Overview

Many Yaqui in Mexico live on reserved land in the state of Sonora. Others formed neighborhoods (colonias or colonies) in various cities. In the city of Hermosillo, colonies such as El Coloso, La Matanza, and Sarmiento are known as Yaqui districts; Yaqui residents there continue the culture and traditions of the Yaqui Nation.

In the late 1960s, several Yaqui in Arizona, among them Anselmo Valencia Tori and Fernando Escalante, started development of a tract of land about 8 km to the west of the Yaqui community of Hu'upa, calling it New Pascua (in Spanish, Pascua Nuevo). This community has a population (estimated in 2006) of about 4,000; most of the middle-aged population of New Pascua speaks English, Spanish, and a moderate amount of Yaqui. Many older people speak the Yaqui language fluently, and a growing number of youth are learning the Yaqui language in addition to English and Spanish.

In Guadalupe, Arizona, established in 1904 and incorporated in 1975, more than 44 percent of the population is Native American, and many are trilingual in Yaqui, English and Spanish. A Yaqui neighborhood, Penjamo, is located in South Scottsdale, Arizona.

More than 13,000 Yaqui are citizens, or members, of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, which is based in Tucson. The Texas Band of Yaqui Indians, a state-recognized Tribe under Resolution SR#989 sponsored by state Sen. Charles Perry, consists of descendants of a band of Mountain Yaqui "who entered the State of Texas in the years of 1870–1875 under the leadership of Ya'ut (leader) Ave'lino Covajori Valenzuela Urquides".[2] The Texas Band of Yaqui Indians, population 900-plus, is petitioning for federal recognition.[3]

Language

The Yaqui language belongs to the Uto-Aztecan language family. Yaqui speak a Cahitan language, a group of about 10 mutually-intelligible languages formerly spoken in much of the states of Sonora and Sinaloa. Most of the Cahitan languages are extinct; only the Yaqui and Mayo still speak their language.[4] About 15,000 Yaqui speakers live in Mexico and 1,000 in the US, mostly Arizona.[5]

The Yaqui call themselves Hiaki or Yoeme, the Yaqui word for person (yoemem or yo'emem meaning "people").[6] The Yaqui call their homeland Hiakim, from which some say the name "Yaqui" is derived. They may also describe themselves as Hiaki Nation or Pascua Hiaki, meaning "The Easter People", as most had converted to Catholicism under Jesuit influence in colonial Mexico. Many folk etymologies account for how the Yoeme came to be known as the "Yaqui".[7]

Yaqui is a tonal language, with a tonal accent on either the first or the second syllable of the word. The syllables which follow the tone are all high; see Pitch-accent language#Yaqui.

History

1530s–1820s: Conquistadors and missionaries

When the Spanish first came into contact with the Yaqui in 1533, the Yaqui occupied a territory along the lower course of the Yaqui River. They were estimated to number 30,000 people living in 80 villages in an area about 60 miles (100 km) long and 15 miles (25 km) wide. Some Yaqui lived near the mouth of the river and lived off of the resources of the sea. Most lived in agricultural communities, growing beans, maize, and squash on land inundated by the river every year. Others lived in the deserts and mountains and depended upon hunting and gathering.[8]

Captain Diego de Guzmán, leader of an expedition to explore lands north of the Spanish settlements, encountered the Yaqui in 1533. A large number of Yaqui warriors confronted the Spaniards on a level plain. Their leader, an old man, drew a line in the dirt and told the Spanish not to cross it. He denied the Spanish request for food. A battle ensued. The Spanish claimed victory, although they retreated. Thus began 40 years of struggle, often armed, by the Yaqui to protect their culture and lands.

In 1565, Francisco de Ibarra attempted, but failed, to establish a Spanish settlement in Yaqui territory. What probably saved the Yaqui from an early invasion by the Spaniards was the lack of silver and other precious metals in their territory. In 1608, the Yaqui and 2,000 Indian allies, mostly Mayo, were victorious over the Spanish in two battles. A peace agreement in 1610 brought gifts from the Spanish and, in 1617, an invitation by the Yaquis for the Jesuit missionaries to stay and teach them.[9]

The Yaqui lived in a mutually advantageous relationship with the Jesuits for 120 years. Most of them converted to Christianity while retaining many traditional beliefs. The Jesuit rule over the Yaqui was stern but the Yaqui retained their land and their unity as a people. The Jesuits introduced wheat, cattle, and horses.

The Yaqui prospered and the missionaries were allowed to extend their activities further north. The Jesuit success was facilitated by the fact that the nearest Spanish settlement was 100 miles away and the Yaqui were able to avoid interaction with Spanish settlers, soldiers and miners. Important, too, was that epidemics of European diseases that destroyed many Indigenous populations appear not to have seriously impacted the Yaqui. The reputation of the Yaqui as warriors, plus the protection afforded by the Jesuits, perhaps shielded the Yaqui from Spanish slavers. The Jesuits persuaded the Yaqui to settle into eight towns: Bácum, Benem, Cócorit, Huirivis, Pótam, Rahum, Tórim, and Vícam.[10]

However, by the 1730s, Spanish settlers and miners were encroaching on Yaqui land and the Spanish colonial government began to alter the arms-length relationship. This created unrest among the Yaqui and led to a brief but bloody Yaqui and Mayo revolt in 1740. One thousand Spanish and 5,000 Native Americans were killed and the animosity lingered. The missions declined and the prosperity of the earlier years was never regained. The Jesuits were expelled from Mexico in 1767 and the Franciscan priests who replaced them never gained the confidence of the Yaqui.

An uneasy peace between the Spaniards and the Yaqui endured for many years after the revolt, with the Yaqui maintaining their tight-knit organization and most of their independence from Spanish and, after 1821, Mexican rule.[11]

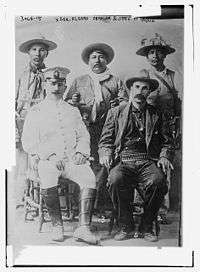

1820s–1920s: Yaqui Wars and enslavement

During Mexico's struggle for independence from Spain in the early 19th century, the Yaqui showed that they still considered themselves independent and self-governing. After Mexico won its independence, the Yaqui refused to pay taxes to the new government. A Yaqui revolt in 1825 was led by Juan Banderas. Banderas wished to unite the Mayo, Opata, Pima, and Yaqui into a state that would be autonomous, or independent of Mexico. The combined Indian force drove the Mexicans out of their territories, but Banderas was eventually defeated and executed in 1833. This led to a succession of revolts as the Yaqui resisted the Mexican government's attempts to gain control of the Yaqui and their lands.

The Yaqui supported the French during the brief reign of Maximilian I of Mexico in the 1860s. Under the leadership of Jose Maria Leyva, known as Cajemé, the Yaqui continued the struggle to maintain their independence until 1887, when Cajeme was caught and executed. The war featured a succession of brutalities by the Mexican authorities, including a massacre in 1868, in which the Army burned 150 Yaqui to death inside a church.

The Yaqui were impoverished by a new series of wars as the Mexican government adopted a policy of confiscation and distribution of Yaqui lands.[12][13] Many displaced Yaquis joined the ranks of warrior bands, who remained in the mountains carrying on a guerrilla campaign against the Mexican Army.

During the 34-year rule of Mexican dictator Porfirio Diaz, the government repeatedly provoked the Yaqui remaining in Sonora to rebellion in order to seize their land for exploitation by investors for both mining and agricultural use.[12] Many Yaqui were sold at 60 pesos a head to the owners of sugar cane plantations in Oaxaca and the tobacco planters of the Valle Nacional, while thousands more were sold to the henequen plantation owners of the Yucatán.[12]

By 1908, at least 5,000 Yaqui had been sold into slavery.[12][13] At Valle Nacional, the enslaved Yaquis were worked until they died.[12] While there were occasional escapes, the escapees were far from home and, without support or assistance, most died of hunger while begging for food on the road out of the valley toward Córdoba.[12]

At Guaymas, thousands more Yaquis were put on boats and shipped to San Blas, where they were forced to walk more than 200 miles to San Marcos and its train station.[12] Many women and children could not withstand the three-week journey over the mountains, and their bodies were left by the side of the road.[12] The Mexican government established large concentration camps at San Marcos, where the remaining Yaqui families were broken up and segregated.[12] Individuals were then sold into slavery inside the station and packed into train cars which took them to Veracruz, where they were embarked yet again for the port town of Progreso in the Yucatán. There they were transported to their final destination, the nearby henequen plantations.[12]

On the plantations, the Yaquis were forced to work in the tropical climate of the area from dawn to dusk.[12] Yaqui women were allowed to marry only non-native Chinese workers.[12] Given little food, the workers were beaten if they failed to cut and trim at least 2,000 henequen leaves per day, after which they were then locked up every night.[12] Most of the Yaqui men, women and children sent for slave labor on the plantations died there, with two-thirds of the arrivals dying within a year.[12]

During this time, Yaqui resistance continued. By the early 1900s, after "extermination, military occupation, and colonization" had failed to halt Yaqui resistance to Mexican rule, many Yaquis assumed the identities of other Tribes and merged with the Mexican population of Sonora in cities and on haciendas.[13] Others left Mexico for the United States, establishing enclaves in southern Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California.[12]

Many Yaqui living in southern Arizona regularly returned to Sonora after working and earning money in the U.S., often for the purpose of smuggling firearms and ammunition to those Yaqui still fighting the Mexican government.[12] Skirmishes continued until 1927, when the last major battle between the Mexican Army and the Yaqui was fought at Cerro del Gallo Mountain. By employing heavy artillery, machine guns, and planes of the Mexican Air Force to shell, bomb, and strafe Yaqui villages, Mexican authorities eventually prevailed.[14]

The objective of the Yaqui and their frequent allies, the Mayo people, remained the same during almost 400 years of interaction with the Jesuits and the Spanish and Mexican governments: independent local government and management of their own lands.

1920s–1930s: Cárdenas and Yaqui independence

In 1917, General Lázaro Cárdenas of the Constitutionalist army defeated the Yaqui. But in 1937, as president of the republic, he reserved 500,000 hectares of ancestral lands on the north bank of the Yaqui River, ordered the construction of a dam to provide irrigation water to the Yaqui, [15] and provided advanced agricultural equipment and water pumps.[16] Thus, the Yaqui continued to maintain a degree of independence from Mexican rule.[17]

In 1939, the Yaqui produced 3,500 tons of wheat, 500 tons of maize, and 750 tons of beans; whereas, in 1935, they had produced only 250 tons of wheat and no maize or beans.[18]

According to the official government report on the sexenio (six-year term) of Cárdenas, the section of the Department of Indigenous Affairs (which Cárdenas established as a cabinet level post in 1936) stated the Yaqui population was 10,000; 3,000 were children younger than 5.

Today, the Mexican municipality of Cajemé is named after the fallen Yaqui leader.[11]

Lifestyle

In the past, the Yaqui subsisted on agriculture, growing beans, corn and squash (like many of the Indigenous peoples of the region). The Yaqui who lived in the Río Yaqui region and in coastal areas of Sonora and Sinaloa fished as well as farmed. The Yaqui also made cotton products. The Yaqui have always been skillful warriors. The Yaqui Indians have been historically described as quite tall in stature.[19]

Traditionally, a Yaqui house consisted of three rectangular sections: the bedroom, the kitchen, and a living room, called the "portal". Floors would be made of wooden supports, walls of woven reeds, and the roof of reeds coated with thick layers of mud for insulation. Branches might be used in living room construction for air circulation; a large part of the day was spent here, especially during the hot months. A home would also have a patio. Since the time of the adoption of Christianity, many Yaquis have a wooden cross placed in front of the house, and special attention is made to its placement and condition during Waresma (Lent).[20]

Yaqui cosmology and religion

The Yaqui conception of the world is considerably different from that of their European-Mexican and European-American neighbors. For example, many Yoemem believe that the universe is composed of overlapping yet distinct worlds or places, called aniam. Nine or more different aniam are recognized: sea ania: flower world, yo ania: enchanted world, tenku ania: a dream world, tuka ania: night world, huya ania: wilderness world, nao ania: corncob world, kawi ania: mountain world, vawe ania: world under the water, teeka ania: world from the sky up through the universe. Each of these worlds has its own distinct qualities, as well as forces, and Yoeme relate deer dancing with three of them, since the deer emerges from yo ania, an enchanted home, into the wilderness world, huya ania, and dances in the flower world, sea ania, which can be accessed through the deer dance.[21] Much Yaqui ritual is centered upon perfecting these worlds and eliminating the harm that has been done to them, especially by people. Many Yaqui have combined such ideas with their practice of Catholicism, and believe that the existence of the world depends on their annual performance of the Lenten and Easter rituals.[19]

The Yaqui religion, which is a syncretic religion of old Yaqui beliefs and practices, and the Christian teachings of Jesuit missionaries, relies upon song, music, prayer, and dancing, all performed by designated members of the community. They have woven numerous Roman Catholic traditions into the old ways and vice versa.[19] For instance, the Yaqui deer song (maso bwikam) accompanies the deer dance, which is performed by a pascola (Easter, from the Spanish pascua) dancer, also known as a "deer dancer". Pascolas perform at religio-social functions many times of the year, but especially during Lent and Easter.[19] The Yaqui deer song ritual is in many ways similar to the deer song rituals of neighboring Uto-Aztecan people, such as the Mayo. The Yaqui deer song is more central to the cultus of its people and is strongly tied into Roman Catholic beliefs and practices. There are various societies among the Yaqui people who play a significant role in the performance of Yaqui ceremonies, including: The Prayer Leaders, Kiyohteis (Female Church Assistants), Vanteareaom (Female Flag Bearers), Anheiltom (Angels), Kohtumvre Ya’ura (Fariseo Society), Kantoras (female singers), officios (Pahko’ola and Deer Dance societies), Wiko Yau’ra society, and Matachinim (Matachin Society dancers).

Flowers are very important in the Yaqui culture. According to Yaqui teachings, flowers sprang up from the drops of blood that were shed at the Crucifixion. Flowers are viewed as the manifestation of souls. Occasionally Yaqui men may greet a close male friend with the phrase Haisa sewa? ("How is the flower?").[19]

Yaqui in the United States

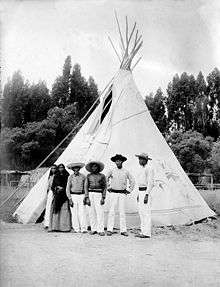

.jpg)

As a result of the wars between Mexico and the Yaqui, many fled to the United States. Most settled in urban barrios, including Barrio Libre and Pascua in Tucson, and Guadalupe and Scottsdale in the Phoenix area. Yaquis built homes of scrap lumber, railroad ties and other materials, eking out an existence while taking great pains to continue the Easter Lenten ceremonies so important to community life. They found work as migrant farm laborers and in other rural occupations.

In the early 1960s, Yaqui spiritual leader Anselmo Valencia Tori approached University of Arizona anthropologist Edward Holland Spicer, an authority on the Yaqui, and asked for assistance in helping the Yaqui people. Spicer, Muriel Thayer Painter and others created the Pascua Yaqui Association. U.S. Representative Morris Udall agreed to aid the Yaquis in securing a land base. In 1964, the U.S. government granted the Yaqui 817,000 m2 of land southwest of Tucson, Arizona. It was held in trust for the people. Under Valencia and Raymond Ybarra, the Pascua Yaqui Association developed homes and other infrastructure at the site.

Realizing the difficulties of developing the community (known as New Pascua) without the benefit of federal Tribal status, Ybarra and Valencia met with U.S. Senator Dennis DeConcini (D-Ariz.) in the early months of 1977 to urge him to introduce legislation to provide complete federal recognition of the Yaqui people living on the land conveyed to the Pascua Yaqui Association by the United States through the Act of October 8, 1964 (78 Stat. 1197).

Senator DeConcini introduced a federal recognition bill, S.1633 on June 7, 1977. After extensive hearings and consideration, it was passed by the Senate on April 5, 1978 and became public law, PL 95-375, on September 18, 1978. The law established a government-to-government relationship between the United States and the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, and gave reservation status to Pascua Yaqui lands. The Pascua Yaqui Tribe was the last Tribe recognized prior to the BIA Federal Acknowledgement Process established in 1978.

In 2008, the Pascua Yaqui Tribe counted 11,324 voting members.[22]

Notable Yaqui

- Alfonso Bedoya (1904–1957), actor, famous for the line, "Badges? We ain't got no badges. We don't need no badges. I don't have to show you any stinkin' badges!" in the 1948 film The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

- Raul (Roy) Perez Benavidez, a member of the highly classified Studies and Observations Group during the Vietnam War. He received the Medal of Honor for his actions in eastern Cambodia.[23]

- Rod Coronado (Pascua Yaqui), an eco-anarchist and animal rights activist.

- Anita Endrezze (Yaqui), artist and poet.[24][25]

- Mario Martinez (Pascua Yaqui), painter living in New York[26]

- Rick Mora (Yaqui/Apache), actor and model.

- Marcos A. Moreno (Pascua Yaqui), public health advocate, medical research scholar and the first member from the Pascua Yaqui Reservation to graduate from an Ivy League University. Recipient of the national Morris K. and Stewart L. Udall Foundation award for research in medicine and public health work with under-served communities.[27]

- Tsi-Cy-Altsa Deborah Parker, daughter of a Tulalip Tribes father and a Yaqui mother. Former vice chairwoman of the Tulalip Tribes; leading advocate for expansion of the Violence Against Women's Act to include protections for Native American women; appointed by Senator Bernie Sanders (D-Vermont), to the 2016 Democratic National Convention's Platform Committee; vice chairwoman, Our Revolution, a progressive political action organization.[28][29]

- Marty Perez (Yaqui/Mission Indian), second baseman and shortstop in the 1960s and 1970s for the California Angels, Atlanta Braves, San Francisco Giants and Oakland A's. His Yaqui ancestors were from Altar, Oquitoa and Magdalena de Kino, Sonora. His sister, Patricia Martinez, served on the Kern County Human Relations Commission 1997-2001 and was a candidate for the Delano Joint Union High School District Board of Directors in 2000.

- Iz Sotelo Ramirez (Texas Band of Yaqui Indians), governor/chairman of the Texas Band of Yaqui Indians Tribal Council.[30]

- Rion J. Ramirez (Pascua Yaqui/Turtle Mountain Chippewa), general counsel for Port Madison Enterprises, the economic development arm of the Suquamish Tribe; and Obama appointee to the Commission on White House Fellowships.[31]

- Lolly and Pat Vegas (Yaqui/Shoshone/Mexican), musicians and vocalists of the Native American rock band Redbone. They were inducted into the Native American Music Hall of Fame in 2008.[32]

- Anselmo Valencia Tori (Pascua Yaqui), spiritual leader and Tribal elder. Led the Tribe through its fight to gain federal recognition from Congress in 1978.[33]

- Ritchie Valens (1941–1959), rock and roll pioneer, singer, songwriter, and guitarist.[34]

See also

- Yaqui Uprising

- Battle of Bear Valley

- Don Juan Matus, an alleged Yaqui sorcerer, described in the Carlos Castaneda book series

- Aqua Prieta Pipeline

- The Teachings of Don Juan, a book about an alleged Yaqui sorcerer

References

- (Data by INALI counting only those who speak the Yaqui language )

- "The Texas Band of Yaqui Indians - About Us / Enrollment". The Texas Band of Yaqui Indians.

- "Home". Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- Hu-Dehart, Evelyn Missionaries Miners and Indians: Spanish Contact with the Yaqui Nation of Northwestern New Spain. Tucson: U of AZ Press, 1981, p. 10

- Guerrero, Lilian. "Grammatical Borrowing in Yaqui." http://lilianguerrero.weebly.com/uploads/2/8/1/3/2813317/estrada__guerrero-yaqui_borrowing.pdf, accessed 5 May 2012

- "Yaqui." U*X*L Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. U*X*L. 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2012 from HighBeam Research: http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G2-3048800047.html

- "Yaqui." Every Culture. http://www.everyculture.com/Middle-America-Caribbean/Yaqui-Orientation.html, accessed 6 May 2012

- Hu-Dehart, pp. 10-11

- Hu-Dehart, pp. 15, 19-20, 27-30

- Spicer. Edward H. Cycles of Conquest. Tucson: U of AZ Press, 1986, pp. 49-50

- Edward H. Spicer (1967), Cycles of Conquest: The Impact of Spain, Mexico, and the United States on Indians of the Southwest, 1533-1960 University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona. p. 55

- Turner, John Kenneth, Barbarous Mexico, Chicago: C.H. Kerr & Co., 1910, pp. 41–77

- Spicer, pp. 80–82

- Spicer, pp. 59–83

- Seis Años de Gobierno al Servicio de México, 1934-1940. Mexico: Nacional Impresora S.A., 1940, 372.

- Seis Años, p. 376.

- Spicer, pp. 81–85

- ’’Seis Años’’, p. 375.

- Spicer, E. H. 1980. The Yaquis: A Cultural History, University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona.

- McGuire, Thomas R. (1986). Politics and Ethnicity on the Rio Yaqui: Potam Revisited. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0816508933.

- Shorter, David Delgado (December 1, 2007). "Hunting for History in Potam Pueblo: A Yoeme (Yaqui) Indian Deer Dancing Epistemology" (PDF). Folklore. 118 (3): 282–306. doi:10.1080/00155870701621780. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- Enric Volante Arizona Daily Star. "1 incumbent out, 2 added to Pascua Yaqui council". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- "Hispanics in the United States Army". Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- Anita Endrezze

- "Anita Endrezze". Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- "Mario Martinez: Contemporary Native Painting - Press". Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- Star, Nick O'Gara Arizona Daily. "Prestigious Udall award goes to Yaqui student from Tucson".

- "Deborah Parker Tsi-Cy-Altsa (Tulalip/Yaqui) | Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs". www.wcsap.org. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- "Deborah Parker | National Indigenous Women's Resource Center".

- "About Us". The Texas Band of Yaqui Indians.

- "Rion Joaquin Ramirez". Tulalip News.

- "Redbone". Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- Innes, Stephanie (May 5, 1998). "Yaquis mourn death of a spiritual leader". Tucson Citizen. Tucson, Arizona.

- "Did you know they are Native American?". Native American Music Awards.

Bibliography

- Folsom, Raphael Brewster: The Yaquis and the Empire: Violence, Spanish Imperial Power, and the Native Resilience in Colonial Mexico. Yale University Press, New Haven 2014, ISBN 978-0-300-19689-4. (Contents)

- Miller, Mark E. "The Yaquis Become 'American' Indians." The Journal of Arizona History (1994).

- Miller, Mark E. Forgotten Tribes: Unrecognized Indians and the Federal Acknowledgment Process (chapter on the Yaquis). (2004)

- Sheridan, T.E. 1988. Where the Dove Calls: The Political Ecology of a Peasant Corporate Community in Northwestern Mexico. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- http://aip.cornell.edu/people/marcos-moreno

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yaqui. |

- The Official Website of the Pascua Yaqui Government

- Escuela Autónoma para la formación artística de la Tribu Yaqui en Vícam,Sonora

- The Website of the Texas Band of Yaqui Indians

- The Un-Official Website of Yoemem/Yaquis in Mexico

- Pascua Yaqui Tribe Charitable Organization

- 15 Flower World Variations - adapted by Jerome Rothenberg from Yaqui Deer Dance Songs

- (in English and Spanish) Vachiam eecha Yaqui cuadernos

- (in English and Spanish) Vachiam eecha non-flash version

- Hector O. Valencia's War Record

- Dario N. Mellado (Fine Art & Illustration).

- Richard Demers, Fernando Escalante and Eloise Jelinek "Prominence in Yaqui Words". International Journal of American Linguistics, Vol. 65, No. 1 (Jan., 1999), pp. 40–55 (on JSTOR), on the tones in Yaqui.