Madagascar

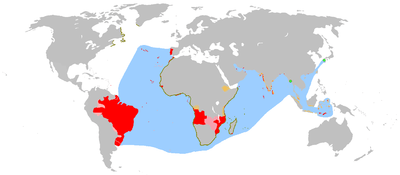

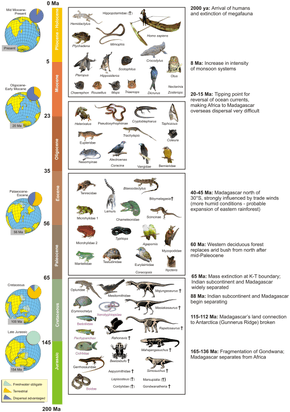

Madagascar (/ˌmædəˈɡæskər, -kɑːr/; Malagasy: Madagasikara), officially the Republic of Madagascar (Malagasy: Repoblikan'i Madagasikara Malagasy pronunciation: [republiˈkʲan madaɡasˈkʲarə̥]; French: République de Madagascar), and previously known as the Malagasy Republic, is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately 400 kilometres (250 miles) off the coast of East Africa. At 592,800 square kilometres (228,900 sq mi) Madagascar is the world's second-largest island country.[13] The nation comprises the island of Madagascar (the fourth-largest island in the world) and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Following the prehistoric breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana, Madagascar split from the Indian subcontinent around 88 million years ago, allowing native plants and animals to evolve in relative isolation. Consequently, Madagascar is a biodiversity hotspot; over 90% of its wildlife is found nowhere else on Earth. The island's diverse ecosystems and unique wildlife are threatened by the encroachment of the rapidly growing human population and other environmental threats.

Republic of Madagascar | |

|---|---|

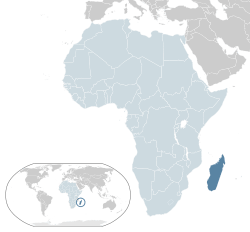

Location of Madagascar (dark blue) – in Africa (light blue & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Antananarivo 18°55′S 47°31′E |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2004[2]) | |

| Religion (2010)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Malagasy[4][5] |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic |

• President | Andry Rajoelina |

| Christian Ntsay | |

• Senate President | Rivo Rakotovao |

• President of the National Assembly | Christine Razanamahasoa[6] |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| National Assembly | |

| Independence | |

• from France | 26 June 1960 |

• Current constitution | 17 November 2010 |

| Area | |

• Total | 587,041 km2 (226,658 sq mi) (46th) |

• Water | 5,501 km2 (2,124 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 0.9% |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 26,262,313[7][8] (52nd) |

• Density | 35.2/km2 (91.2/sq mi) (174th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $45.948 billion[9] |

• Per capita | $1,697[9] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $12.734 billion[9] |

• Per capita | $471[9] |

| Gini (2010) | 44.1[10] medium |

| HDI (2018) | low · 162nd |

| Currency | Malagasy ariary (MGA) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

| UTC+3 (not observed[12]) | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +261[12] |

| ISO 3166 code | MG |

| Internet TLD | .mg |

The archaeological evidence of the earliest human foraging on Madagascar may date up to 10,000 years ago.[14] Human settlement of Madagascar occurred between 350 BC and 550 AD by Indianized Austronesian peoples, arriving on outrigger canoes from Indonesia. The social and religious situation of Indonesia during those times were that of Hinduism and Buddhism, along with native Indonesian culture. These were joined around the 9th century AD by Bantu migrants crossing the Mozambique Channel from East Africa. Other groups continued to settle on Madagascar over time, each one making lasting contributions to Malagasy cultural life. The Malagasy ethnic group is often divided into 18 or more subgroups, of which the largest are the Merina of the central highlands.

Until the late 18th century, the island of Madagascar was ruled by a fragmented assortment of shifting sociopolitical alliances. Beginning in the early 19th century, most of the island was united and ruled as the Kingdom of Madagascar by a series of Merina nobles. The monarchy ended in 1897 when the island was absorbed into the French colonial empire, from which the island gained independence in 1960. The autonomous state of Madagascar has since undergone four major constitutional periods, termed republics. Since 1992, the nation has officially been governed as a constitutional democracy from its capital at Antananarivo. However, in a popular uprising in 2009, president Marc Ravalomanana was made to resign and presidential power was transferred in March 2009 to Andry Rajoelina. Constitutional governance was restored in January 2014, when Hery Rajaonarimampianina was named president following a 2013 election deemed fair and transparent by the international community. Madagascar is a member of the United Nations, the African Union (AU), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), and the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie.

Madagascar belongs to the group of least developed countries, according to the United Nations.[15] Malagasy and French are both official languages of the state. The majority of the population adheres to traditional beliefs, Christianity, or an amalgamation of both. Ecotourism and agriculture, paired with greater investments in education, health, and private enterprise, are key elements of Madagascar's development strategy. Under Ravalomanana, these investments produced substantial economic growth, but the benefits were not evenly spread throughout the population, producing tensions over the increasing cost of living and declining living standards among the poor and some segments of the middle class. As of 2017, the economy has been weakened by the 2009–2013 political crisis, and quality of life remains low for the majority of the Malagasy population.

Etymology

In the Malagasy language, the island of Madagascar is called Madagasikara (Malagasy pronunciation: [madaɡasʲˈkʲarə̥]) and its people are referred to as Malagasy.[16] The island's appellation "Madagascar" is not of local origin but rather was popularized in the Middle Ages by Europeans.[17] The name Madageiscar was first recorded in the memoirs of 13th-century Venetian explorer Marco Polo as a corrupted transliteration of the name Mogadishu, the Somali port with which Polo had confused the island.[18]

On St. Laurence's Day in 1500, Portuguese explorer Diogo Dias landed on the island and named it São Lourenço. Polo's name was preferred and popularized on Renaissance maps. No single Malagasy-language name predating Madagasikara appears to have been used by the local population to refer to the island, although some communities had their own name for part or all of the land they inhabited.[18]

Geography

At 592,800 square kilometres (228,900 sq mi),[19] Madagascar is the world's 47th largest country,[20] the 2nd largest island country[13] and the fourth-largest island.[19] The country lies mostly between latitudes 12°S and 26°S, and longitudes 43°E and 51°E.[21] Neighboring islands include the French territory of Réunion and the country of Mauritius to the east, as well as the state of Comoros and the French territory of Mayotte to the north west. The nearest mainland state is Mozambique, located to the west.

The prehistoric breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana separated the Madagascar–Antarctica–India landmass from the Africa–South America landmass around 135 million years ago. Madagascar later split from India about 88 million years ago during the late Cretaceous period allowing plants and animals on the island to evolve in relative isolation.[22] Along the length of the eastern coast runs a narrow and steep escarpment containing much of the island's remaining tropical lowland forest.

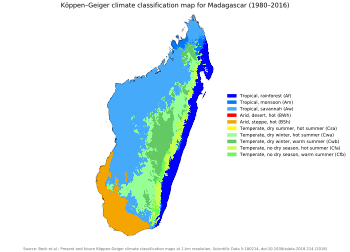

To the west of this ridge lies a plateau in the center of the island ranging in altitude from 750 to 1,500 m (2,460 to 4,920 ft) above sea level. These central highlands, traditionally the homeland of the Merina people and the location of their historic capital at Antananarivo, are the most densely populated part of the island and are characterized by terraced, rice-growing valleys lying between grassy hills and patches of the subhumid forests that formerly covered the highland region. To the west of the highlands, the increasingly arid terrain gradually slopes down to the Mozambique Channel and mangrove swamps along the coast.[23]

Madagascar's highest peaks rise from three prominent highland massifs: Maromokotro 2,876 m (9,436 ft) in the Tsaratanana Massif is the island's highest point, followed by Boby Peak 2,658 m (8,720 ft) in the Andringitra Massif, and Tsiafajavona 2,643 m (8,671 ft) in the Ankaratra Massif. To the east, the Canal des Pangalanes is a chain of man-made and natural lakes connected by canals built by the French just inland from the east coast and running parallel to it for some 600 km (370 mi).[24]

The western and southern sides, which lie in the rain shadow of the central highlands, are home to dry deciduous forests, spiny forests, and deserts and xeric shrublands. Due to their lower population densities, Madagascar's dry deciduous forests have been better preserved than the eastern rain forests or the original woodlands of the central plateau. The western coast features many protected harbors, but silting is a major problem caused by sediment from the high levels of inland erosion carried by rivers crossing the broad western plains.[24]

Climate

The combination of southeastern trade winds and northwestern monsoons produces a hot rainy season (November–April) with frequently destructive cyclones, and a relatively cooler dry season (May–October). Rain clouds originating over the Indian Ocean discharge much of their moisture over the island's eastern coast; the heavy precipitation supports the area's rainforest ecosystem. The central highlands are both drier and cooler while the west is drier still, and a semi-arid climate prevails in the southwest and southern interior of the island.[23]

Tropical cyclones cause damage to infrastructure and local economies as well as loss of life.[25] In 2004, Cyclone Gafilo became the strongest cyclone ever recorded to hit Madagascar. The storm killed 172 people, left 214,260 homeless[26] and caused more than US$250 million in damage.[27]

Ecology

As a result of the island's long isolation from neighboring continents, Madagascar is home to various plants and animals found nowhere else on Earth.[28][29] Approximately 90% of all plant and animal species found in Madagascar are endemic.[30] This distinctive ecology has led some ecologists to refer to Madagascar as the "eighth continent",[31] and the island has been classified by Conservation International as a biodiversity hotspot.[28]

More than 80 percent of Madagascar's 14,883 plant species are found nowhere else in the world, including five plant families.[32] The family Didiereaceae, composed of four genera and 11 species, is limited to the spiny forests of southwestern Madagascar.[23] Four-fifths of the world's Pachypodium species are endemic to the island.[33] Three-fourths[34] of Madagascar's 860[32] orchid species are found here alone, as are six of the world's nine baobab species.[35] The island is home to around 170 palm species, three times as many as on all of mainland Africa; 165 of them are endemic.[34] Many native plant species are used as herbal remedies for a variety of afflictions. The drugs vinblastine[36][37] and vincristine[36][38] are vinca alkaloids,[39][40] used to treat Hodgkin's disease,[41] leukemia,[42] and other cancers,[43] were derived from the Madagascar periwinkle.[44][45] The traveler's palm, known locally as ravinala[46] and endemic to the eastern rain forests,[47] is highly iconic of Madagascar and is featured in the national emblem as well as the Air Madagascar logo.[48]

Like its flora, Madagascar's fauna is diverse and exhibits a high rate of endemism. Lemurs have been characterized as "Madagascar's flagship mammal species" by Conservation International.[28] In the absence of monkeys and other competitors, these primates have adapted to a wide range of habitats and diversified into numerous species. As of 2012, there were officially 103 species and subspecies of lemur,[50] 39 of which were described by zoologists between 2000 and 2008.[51] They are almost all classified as rare, vulnerable, or endangered. At least 17 species of lemur have become extinct since humans arrived on Madagascar, all of which were larger than the surviving lemur species.[52]

A number of other mammals, including the cat-like fossa, are endemic to Madagascar. Over 300 species of birds have been recorded on the island, of which over 60 percent (including four families and 42 genera) are endemic.[28] The few families and genera of reptile that have reached Madagascar have diversified into more than 260 species, with over 90 percent of these being endemic[53] (including one endemic family).[28] The island is home to two-thirds of the world's chameleon species,[53] including the smallest known,[54] and researchers have proposed that Madagascar may be the origin of all chameleons.

Endemic fish of Madagascar include two families, 15 genera and over 100 species, primarily inhabiting the island's freshwater lakes and rivers. Although invertebrates remain poorly studied on Madagascar, researchers have found high rates of endemism among the known species. All 651 species of terrestrial snail are endemic, as are a majority of the island's butterflies, scarab beetles, lacewings, spiders and dragonflies.[28]

Environmental issues

Madagascar's varied fauna and flora are endangered by human activity.[55] Since the arrival of humans around 2,350 years ago, Madagascar has lost more than 90 percent of its original forest.[56] This forest loss is largely fueled by tavy ("fat"), a traditional slash-and-burn agricultural practice imported to Madagascar by the earliest settlers.[57] Malagasy farmers embrace and perpetuate the practice not only for its practical benefits as an agricultural technique, but for its cultural associations with prosperity, health and venerated ancestral custom (fomba malagasy).[58] As human population density rose on the island, deforestation accelerated beginning around 1,400 years ago.[59] By the 16th century, the central highlands had been largely cleared of their original forests.[57] More recent contributors to the loss of forest cover include the growth in cattle herd size since their introduction around 1,000 years ago, a continued reliance on charcoal as a fuel for cooking, and the increased prominence of coffee as a cash crop over the past century.[60]

According to a conservative estimate, about 40 percent of the island's original forest cover was lost from the 1950s to 2000, with a thinning of remaining forest areas by 80 percent.[61] In addition to traditional agricultural practice, wildlife conservation is challenged by the illicit harvesting of protected forests, as well as the state-sanctioned harvesting of precious woods within national parks. Although banned by then-President Marc Ravalomanana from 2000 to 2009, the collection of small quantities of precious timber from national parks was re-authorized in January 2009 and dramatically intensified under the administration of Andry Rajoelina as a key source of state revenues to offset cuts in donor support following Ravalomanana's ousting.[62]

Invasive species have likewise been introduced by human populations. Following the 2014 discovery in Madagascar of the Asian common toad, a relative of a toad species that has severely harmed wildlife in Australia since the 1930s, researchers warned the toad could "wreak havoc on the country's unique fauna."[63] Habitat destruction and hunting have threatened many of Madagascar's endemic species or driven them to extinction. The island's elephant birds, a family of endemic giant ratites, became extinct in the 17th century or earlier, most probably because of human hunting of adult birds and poaching of their large eggs for food.[64] Numerous giant lemur species vanished with the arrival of human settlers to the island, while others became extinct over the course of the centuries as a growing human population put greater pressures on lemur habitats and, among some populations, increased the rate of lemur hunting for food.[65] A July 2012 assessment found that the exploitation of natural resources since 2009 has had dire consequences for the island's wildlife: 90 percent of lemur species were found to be threatened with extinction, the highest proportion of any mammalian group. Of these, 23 species were classified as critically endangered. By contrast, a previous study in 2008 had found only 38 percent of lemur species were at risk of extinction.[50]

In 2003, Ravalomanana announced the Durban Vision, an initiative to more than triple the island's protected natural areas to over 60,000 km2 (23,000 sq mi) or 10 percent of Madagascar's land surface. As of 2011, areas protected by the state included five Strict Nature Reserves (Réserves Naturelles Intégrales), 21 Wildlife Reserves (Réserves Spéciales) and 21 National Parks (Parcs Nationaux).[66] In 2007 six of the national parks were declared a joint World Heritage Site under the name Rainforests of the Atsinanana. These parks are Marojejy, Masoala, Ranomafana, Zahamena, Andohahela and Andringitra.[67] Local timber merchants are harvesting scarce species of rosewood trees from protected rainforests within Marojejy National Park and exporting the wood to China for the production of luxury furniture and musical instruments.[68] To raise public awareness of Madagascar's environmental challenges, the Wildlife Conservation Society opened an exhibit entitled "Madagascar!" in June 2008 at the Bronx Zoo in New York.[69]

History

Early period

Archaeological finds such as cut marks on bones found in the northwest and stone tools in the northeast indicate that Madagascar was visited by foragers around 2000 BC.[70][71] Early Holocene humans might have existed on the island 10,500 years ago, based on grooves found on elephant bird bones left by humans.[72] However, a counterstudy concluded that human-made marks date to 1,200 years ago at the earliest, in which the previously mentioned bone damage may have been made by scavengers, ground movements or cuts from the excavation process.[73]

Traditionally, archaeologists have estimated that the earliest settlers arrived in successive waves in outrigger canoes from the Sunda islands (Malay Archipelago) throughout the period between 350 BC and 550 AD, while others are cautious about dates earlier than 250 AD. In either case, these dates make Madagascar the last major landmass on Earth to be settled by humans, except for Iceland and New Zealand.[74] It is known that Ma'anyan people were brought as labourer and slaves by Malay and Javanese people in their trading fleets to Madagascar.[75][76][77]

Upon arrival, early settlers practiced slash-and-burn agriculture to clear the coastal rainforests for cultivation. The first settlers encountered Madagascar's abundance of megafauna, including giant lemurs, elephant birds, giant fossa and the Malagasy hippopotamus, which have since become extinct because of hunting and habitat destruction.[78] By 600 AD, groups of these early settlers had begun clearing the forests of the central highlands.[79] Arab traders first reached the island between the 7th and 9th centuries.[80] A wave of Bantu-speaking migrants from southeastern Africa arrived around 1000 AD. South Indian Tamil merchants arrived around 11th century. They introduced the zebu, a type of long-horned humped cattle, which they kept in large herds.[57] Irrigated paddy fields were developed in the central highland Betsileo Kingdom and were extended with terraced paddies throughout the neighboring Kingdom of Imerina a century later.[79] The rising intensity of land cultivation and the ever-increasing demand for zebu pasturage had largely transformed the central highlands from a forest ecosystem to grassland by the 17th century.[57] The oral histories of the Merina people, who may have arrived in the central highlands between 600 and 1,000 years ago, describe encountering an established population they called the Vazimba. Probably the descendants of an earlier and less technologically advanced Austronesian settlement wave, the Vazimba were assimilated or expelled from the highlands by the Merina kings Andriamanelo, Ralambo and Andrianjaka in the 16th and early 17th centuries.[81] Today, the spirits of the Vazimba are revered as tompontany (ancestral masters of the land) by many traditional Malagasy communities.[82]

Arab and Portuguese contacts

.jpg)

Madagascar was an important transoceanic trading hub connecting ports of the Indian Ocean in the early centuries following human settlement.

The written history of Madagascar began with the Arabs, who established trading posts along the northwest coast by at least the 10th century and introduced Islam, the Arabic script (used to transcribe the Malagasy language in a form of writing known as sorabe), Arab astrology, and other cultural elements.[25]

Portuguese

European contact began in 1500, when the Portuguese sea captain Diogo Dias sighted the island, while participating in the 2nd Armada of the Portuguese India Armadas.[19]

Matatana was the first Portuguese settlement on the south coast,10 km west of Fort Dauphin. In 1508, settlers there built a tower a small village, and a stone column. This settlement was established in 1613 at the behest of the viceroy of Portuguese India, Jeronimo de Azevedo.[83]

In 1543, the governor of Portuguese India, Martim Afonso de Sousa, sent an armada to Madagascar, captained by Diogo Soares, to find missing boats belonging to the governor's brother, but no boats where found.[84] One point where the armada language was later given the Spanish equivalent of the captain's name, Diego Suarez, which it held until it was renamed Antsiranana in 1975.

Contacts continued from the 1550s. Several colonization and conversion missions were ordered by King João III and by the Viceroy of India, including one in 1553 by Baltazar Lobo de Sousa. In that mission, according to detailed descriptions by chroniclers Diogo do Couto and João de Barros, emissaries reached the inland via rivers and bays, exchanging goods and even converting one of the local kings.[85]

French

The French established trading posts along the east coast in the late 17th century.[25]

From about 1774 to 1824, Madagascar gained prominence among pirates and European traders, particularly those involved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The small island of Nosy Boroha off the northeastern coast of Madagascar has been proposed by some historians as the site of the legendary pirate utopia of Libertalia.[86] Many European sailors were shipwrecked on the coasts of the island, among them Robert Drury, whose journal is one of the few written depictions of life in southern Madagascar during the 18th century.[87]

The wealth generated by maritime trade spurred the rise of organized kingdoms on the island, some of which had grown quite powerful by the 17th century.[88] Among these were the Betsimisaraka alliance of the eastern coast and the Sakalava chiefdoms of Menabe and Boina on the west coast. The Kingdom of Imerina, located in the central highlands with its capital at the royal palace of Antananarivo, emerged at around the same time under the leadership of King Andriamanelo.[89]

Kingdom of Madagascar

Upon its emergence in the early 17th century, the highland kingdom of Imerina was initially a minor power relative to the larger coastal kingdoms[89] and grew even weaker in the early 18th century when King Andriamasinavalona divided it among his four sons. Following almost a century of warring and famine, Imerina was reunited in 1793 by King Andrianampoinimerina (1787–1810).[90] From his initial capital Ambohimanga,[91] and later from the Rova of Antananarivo, this Merina king rapidly expanded his rule over neighboring principalities. His ambition to bring the entire island under his control was largely achieved by his son and successor, King Radama I (1810–28), who was recognized by the British government as King of Madagascar. Radama concluded a treaty in 1817 with the British governor of Mauritius to abolish the lucrative slave trade in return for British military and financial assistance. Artisan missionary envoys from the London Missionary Society began arriving in 1818 and included such key figures as James Cameron, David Jones and David Griffiths, who established schools, transcribed the Malagasy language using the Roman alphabet, translated the Bible, and introduced a variety of new technologies to the island.[92]

Radama's successor, Queen Ranavalona I (1828–61), responded to increasing political and cultural encroachment on the part of Britain and France by issuing a royal edict prohibiting the practice of Christianity in Madagascar and pressuring most foreigners to leave the territory. William Ellis (missionary) described his visits made during her reign in his book Three Visits to Madagascar during the years 1853, 1854 and 1856. The Queen made heavy use of the traditional practice of fanompoana (forced labor as tax payment) to complete public works projects and develop a standing army of between 20,000 and 30,000 Merina soldiers, whom she deployed to pacify outlying regions of the island and further expand the Kingdom of Merina to encompass most of Madagascar. Residents of Madagascar could accuse one another of various crimes, including theft, Christianity and especially witchcraft, for which the ordeal of tangena was routinely obligatory. Between 1828 and 1861, the tangena ordeal caused about 3,000 deaths annually. In 1838, it was estimated that as many as 100,000 people in Imerina died as a result of the tangena ordeal, constituting roughly 20 percent of the population.[93] The combination of regular warfare, disease, difficult forced labor and harsh measures of justice resulted in a high mortality rate among soldiers and civilians alike during her 33-year reign, the population of Madagascar is estimated to have declined from around 5 million to 2.5 million between 1833 and 1839.[94]

Among those who continued to reside in Imerina were Jean Laborde, an entrepreneur who developed munitions and other industries on behalf of the monarchy, and Joseph-François Lambert, a French adventurer and slave trader, with whom then-Prince Radama II signed a controversial trade agreement termed the Lambert Charter. Succeeding his mother, Radama II (1861–63) attempted to relax the queen's stringent policies, but was overthrown two years later by Prime Minister Rainivoninahitriniony (1852–1865) and an alliance of Andriana (noble) and Hova (commoner) courtiers, who sought to end the absolute power of the monarch.[25]

Following the coup, the courtiers offered Radama's queen, Rasoherina (1863–68), the opportunity to rule, if she would accept a power sharing arrangement with the Prime Minister: a new social contract that would be sealed by a political marriage between them.[95] Queen Rasoherina accepted, first marrying Rainivoninahitriniony, then later deposing him and marrying his brother, Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony (1864–95), who would go on to marry Queen Ranavalona II (1868–83) and Queen Ranavalona III (1883–97) in succession.[96] Over the course of Rainilaiarivony's 31-year tenure as prime minister, numerous policies were adopted to modernize and consolidate the power of the central government.[97] Schools were constructed throughout the island and attendance was made mandatory. Army organization was improved and British consultants were employed to train and professionalize soldiers.[98] Polygamy was outlawed and Christianity, declared the official religion of the court in 1869, was adopted alongside traditional beliefs among a growing portion of the populace.[97] Legal codes were reformed on the basis of British common law and three European-style courts were established in the capital city.[98] In his joint role as Commander-in-Chief, Rainilaiarivony also successfully ensured the defense of Madagascar against several French colonial incursions.[98]

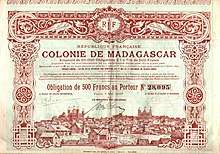

French colonization

Primarily on the basis that the Lambert Charter had not been respected, France invaded Madagascar in 1883 in what became known as the first Franco-Hova War.[99] At the end of the war, Madagascar ceded the northern port town of Antsiranana (Diego Suarez) to France and paid 560,000 francs to Lambert's heirs.[100] In 1890, the British accepted the full formal imposition of a French protectorate on the island, but French authority was not acknowledged by the government of Madagascar. To force capitulation, the French bombarded and occupied the harbor of Toamasina on the east coast, and Mahajanga on the west coast, in December 1894 and January 1895 respectively.[101]

A French military flying column then marched toward Antananarivo, losing many men to malaria and other diseases. Reinforcements came from Algeria and Sub-Saharan Africa. Upon reaching the city in September 1895, the column bombarded the royal palace with heavy artillery, causing heavy casualties and leading Queen Ranavalona III to surrender.[102] France annexed Madagascar in 1896 and declared the island a colony the following year, dissolving the Merina monarchy and sending the royal family into exile on Réunion Island and to Algeria. A two-year resistance movement organized in response to the French capture of the royal palace was effectively put down at the end of 1897.[103]

Under colonial rule, plantations were established for the production of a variety of export crops.[104] Slavery was abolished in 1896 and approximately 500,000 slaves were freed; many remained in their former masters' homes as servants[105] or as sharecroppers; in many parts of the island strong discriminatory views against slave descendants are still held today.[106] Wide paved boulevards and gathering places were constructed in the capital city of Antananarivo[107] and the Rova palace compound was turned into a museum.[108] Additional schools were built, particularly in rural and coastal areas where the schools of the Merina had not reached. Education became mandatory between the ages of 6 to 13 and focused primarily on French language and practical skills.[109]

The Merina royal tradition of taxes paid in the form of labor was continued under the French and used to construct a railway and roads linking key coastal cities to Antananarivo.[110] Malagasy troops fought for France in World War I.[19] In the 1930s, Nazi political thinkers developed the Madagascar Plan that had identified the island as a potential site for the deportation of Europe's Jews.[111] During the Second World War, the island was the site of the Battle of Madagascar between the Vichy government and the British.[112]

The occupation of France during the Second World War tarnished the prestige of the colonial administration in Madagascar and galvanized the growing independence movement, leading to the Malagasy Uprising of 1947.[113] This movement led the French to establish reformed institutions in 1956 under the Loi Cadre (Overseas Reform Act), and Madagascar moved peacefully towards independence.[114] The Malagasy Republic was proclaimed on 14 October 1958, as an autonomous state within the French Community. A period of provisional government ended with the adoption of a constitution in 1959 and full independence on 26 June 1960.[115]

Independent state

Since regaining independence, Madagascar has transitioned through four republics with corresponding revisions to its constitution. The First Republic (1960–72), under the leadership of French-appointed President Philibert Tsiranana, was characterized by a continuation of strong economic and political ties to France. Many high-level technical positions were filled by French expatriates, and French teachers, textbooks and curricula continued to be used in schools around the country. Popular resentment over Tsiranana's tolerance for this "neo-colonial" arrangement inspired a series of farmer and student protests that overturned his administration in 1972.[25]

Gabriel Ramanantsoa, a major general in the army, was appointed interim president and prime minister that same year, but low public approval forced him to step down in 1975. Colonel Richard Ratsimandrava, appointed to succeed him, was assassinated six days into his tenure. General Gilles Andriamahazo ruled after Ratsimandrava for four months before being replaced by another military appointee: Vice Admiral Didier Ratsiraka, who ushered in the socialist-Marxist Second Republic that ran under his tenure from 1975 to 1993.

This period saw a political alignment with the Eastern Bloc countries and a shift toward economic insularity. These policies, coupled with economic pressures stemming from the 1973 oil crisis, resulted in the rapid collapse of Madagascar's economy and a sharp decline in living standards,[25] and the country had become completely bankrupt by 1979. The Ratsiraka administration accepted the conditions of transparency, anti-corruption measures and free market policies imposed by the International Monetary Fund, World Bank and various bilateral donors in exchange for their bailout of the nation's broken economy.[116]

Ratsiraka's dwindling popularity in the late 1980s reached a critical point in 1991 when presidential guards opened fire on unarmed protesters during a rally. Within two months, a transitional government had been established under the leadership of Albert Zafy (1993–96), who went on to win the 1992 presidential elections and inaugurate the Third Republic (1992–2010).[117] The new Madagascar constitution established a multi-party democracy and a separation of powers that placed significant control in the hands of the National Assembly. The new constitution also emphasized human rights, social and political freedoms, and free trade.[25] Zafy's term, however, was marred by economic decline, allegations of corruption, and his introduction of legislation to give himself greater powers. He was consequently impeached in 1996, and an interim president, Norbert Ratsirahonana, was appointed for the three months prior to the next presidential election. Ratsiraka was then voted back into power on a platform of decentralization and economic reforms for a second term which lasted from 1996 to 2001.[116]

The contested 2001 presidential elections in which then-mayor of Antananarivo, Marc Ravalomanana, eventually emerged victorious, caused a seven-month standoff in 2002 between supporters of Ravalomanana and Ratsiraka. The negative economic impact of the political crisis was gradually overcome by Ravalomanana's progressive economic and political policies, which encouraged investments in education and ecotourism, facilitated foreign direct investment, and cultivated trading partnerships both regionally and internationally. National GDP grew at an average rate of 7 percent per year under his administration. In the later half of his second term, Ravalomanana was criticised by domestic and international observers who accused him of increasing authoritarianism and corruption.[116]

Opposition leader and then-mayor of Antananarivo, Andry Rajoelina, led a movement in early 2009 in which Ravalomanana was pushed from power in an unconstitutional process widely condemned as a coup d'état. In March 2009, Rajoelina was declared by the Supreme Court as the President of the High Transitional Authority, an interim governing body responsible for moving the country toward presidential elections. In 2010, a new constitution was adopted by referendum, establishing a Fourth Republic, which sustained the democratic, multi-party structure established in the previous constitution.[117] Hery Rajaonarimampianina was declared the winner of the 2013 presidential election, which the international community deemed fair and transparent.[118]

Government

Structure

Madagascar is a semi-presidential representative democratic multi-party republic, wherein the popularly elected president is the head of state and selects a prime minister, who recommends candidates to the president to form his cabinet of ministers. According to the constitution, executive power is exercised by the government while legislative power is vested in the ministerial cabinet, the Senate and the National Assembly, although in reality these two latter bodies have very little power or legislative role. The constitution establishes independent executive, legislative and judicial branches and mandates a popularly elected president limited to three five-year terms.[19]

The public directly elects the president and the 127 members of the National Assembly to five-year terms. All 33 members of the Senate serve six-year terms, with 22 senators elected by local officials and 11 appointed by the president. The last National Assembly election was held on 20 December 2013[19] and the last Senate election was held on 30 December 2015.[119]

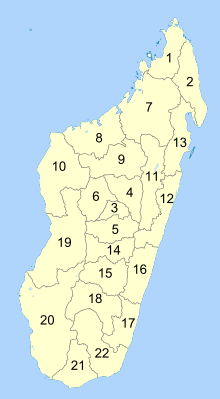

At the local level, the island's 22 provinces are administered by a governor and provincial council. Provinces are further subdivided into regions and communes. The judiciary is modeled on the French system, with a High Constitutional Court, High Court of Justice, Supreme Court, Court of Appeals, criminal tribunals, and tribunals of first instance.[120] The courts, which adhere to civil law, lack the capacity to quickly and transparently try the cases in the judicial system, often forcing defendants to pass lengthy pretrial detentions in unsanitary and overcrowded prisons.[121]

Antananarivo is the administrative capital and largest city of Madagascar.[19] It is located in the highlands region, near the geographic center of the island. King Andrianjaka founded Antananarivo as the capital of his Imerina Kingdom around 1610 or 1625 upon the site of a captured Vazimba capital on the hilltop of Analamanga.[81] As Merina dominance expanded over neighboring Malagasy peoples in the early 19th century to establish the Kingdom of Madagascar, Antananarivo became the center of administration for virtually the entire island. In 1896 the French colonizers of Madagascar adopted the Merina capital as their center of colonial administration. The city remained the capital of Madagascar after regaining independence in 1960. In 2017, the capital's population was estimated at 1,391,433 inhabitants.[122] The next largest cities are Antsirabe (500,000), Toamasina (450,000) and Mahajanga (400,000).[19]

Politics

Since Madagascar gained independence from France in 1960, the island's political transitions have been marked by numerous popular protests, several disputed elections, an impeachment, two military coups and one assassination. The island's recurrent political crises are often prolonged, with detrimental effects on the local economy, international relations and Malagasy living standards. The eight-month standoff between incumbent Ratsiraka and challenger Marc Ravalomanana following the 2001 presidential elections cost Madagascar millions of dollars in lost tourism and trade revenue as well as damage to infrastructure, such as bombed bridges and buildings damaged by arson.[123] A series of protests led by Andry Rajoelina against Ravalomanana in early 2009 became violent, with more than 170 people killed.[124] Modern politics in Madagascar are colored by the history of Merina subjugation of coastal communities under their rule in the 19th century. The consequent tension between the highland and coastal populations has periodically flared up into isolated events of violence.[125]

Madagascar has historically been perceived as being on the margin of mainstream African affairs despite being a founding member of the Organisation of African Unity, which was established in 1963 and dissolved in 2002 to be replaced by the African Union. Madagascar was not permitted to attend the first African Union summit because of a dispute over the results of the 2001 presidential election, but rejoined the African Union in July 2003 after a 14-month hiatus. Madagascar was again suspended by the African Union in March 2009 following the unconstitutional transfer of executive power to Rajoelina.[126] Madagascar is a member of the International Criminal Court with a Bilateral Immunity Agreement of protection for the United States military.[19] Eleven countries have established embassies in Madagascar, including France, the United Kingdom, the United States, China and India,[127] while Madagascar has embassies in sixteen other countries.

Human rights in Madagascar are protected under the constitution and the state is a signatory to numerous international agreements including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.[128] Religious, ethnic and sexual minorities are protected under the law. Freedom of association and assembly are also guaranteed under the law, although in practice the denial of permits for public assembly has occasionally been used to impede political demonstrations.[62][128] Torture by security forces is rare and state repression is low relative to other countries with comparably few legal safeguards, although arbitrary arrests and the corruption of military and police officers remain problems. Ravalomanana's 2004 creation of BIANCO, an anti-corruption bureau, resulted in reduced corruption among Antananarivo's lower-level bureaucrats in particular, although high-level officials have not been prosecuted by the bureau.[62] Accusations of media censorship have risen due to the alleged restrictions on the coverage of government opposition.[129] Some journalists have been arrested for allegedly spreading fake news.[130]

Security

The rise of centralized kingdoms among the Sakalava, Merina and other ethnic groups produced the island's first standing armies by the 16th century, initially equipped with spears but later with muskets, cannons and other firearms.[131] By the early 19th century, the Merina sovereigns of the Kingdom of Madagascar had brought much of the island under their control by mobilizing an army of trained and armed soldiers numbering as high as 30,000.[132] French attacks on coastal towns in the later part of the century prompted then-Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony to solicit British assistance to provide training to the Merina monarchy's army. Despite the training and leadership provided by British military advisers, the Malagasy army was unable to withstand French weaponry and was forced to surrender following an attack on the royal palace at Antananarivo. Madagascar was declared a colony of France in 1897.[133]

The political independence and sovereignty of the Malagasy armed forces, which comprises an army, navy and air force, was restored with independence from France in 1960.[134] Since this time the Malagasy military has never engaged in armed conflict with another state or within its own borders, but has occasionally intervened to restore order during periods of political unrest. Under the socialist Second Republic, Admiral Didier Ratsiraka instated mandatory national armed or civil service for all young citizens regardless of gender, a policy that remained in effect from 1976 to 1991.[135][136] The armed forces are under the direction of the Minister of the Interior[120] and have remained largely neutral during times of political crisis, as during the protracted standoff between incumbent Ratsiraka and challenger Marc Ravalomanana in the disputed 2001 presidential elections, when the military refused to intervene in favor of either candidate. This tradition was broken in 2009, when a segment of the army defected to the side of Andry Rajoelina, then-mayor of Antananarivo, in support of his attempt to force President Ravalomanana from power.[62]

The Minister of the Interior is responsible for the national police force, paramilitary force (gendarmerie) and the secret police.[120] The police and gendarmerie are stationed and administered at the local level. However, in 2009 fewer than a third of all communes had access to the services of these security forces, with most lacking local-level headquarters for either corps.[137] Traditional community tribunals, called dina, are presided over by elders and other respected figures and remain a key means by which justice is served in rural areas where state presence is weak. Historically, security has been relatively high across the island.[62] Violent crime rates are low, and criminal activities are predominantly crimes of opportunity such as pickpocketing and petty theft, although child prostitution, human trafficking and the production and sale of marijuana and other illegal drugs are increasing.[120] Budget cuts since 2009 have severely impacted the national police force, producing a steep increase in criminal activity in recent years.[62]

Administrative divisions

Madagascar is subdivided into 22 regions (faritra).[19] The regions are further subdivided into 119 districts, 1,579 communes, and 17,485 fokontany.[137]

| New regions | Former provinces | Area in km2 | Population 2018 Census[139] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diana (1) | Antsiranana | 19,266 | 889,736 |

| Sava (2) | Antsiranana | 25,518 | 1,123,013 |

| Itasy (3) | Antananarivo | 6,993 | 897,962 |

| Analamanga (4) | Antananarivo | 16,911 | 3,618,128 |

| Vakinankaratra (5) | Antananarivo | 16,599 | 2,074,358 |

| Bongolava (6) | Antananarivo | 16,688 | 674,474 |

| Sofia (7) | Mahajanga | 50,100 | 1,500,227 |

| Boeny (8) | Mahajanga | 31,046 | 931,171 |

| Betsiboka (9) | Mahajanga | 30,025 | 394,561 |

| Melaky (10) | Mahajanga | 38,852 | 309,805 |

| Alaotra Mangoro (11) | Toamasina | 31,948 | 1,255,514 |

| Atsinanana (12) | Toamasina | 21,934 | 1,484,403 |

| Analanjirofo (13) | Toamasina | 21,930 | 1,152,345 |

| Amoron'i Mania (14) | Fianarantsoa | 16,141 | 833,919 |

| Haute-Matsiatra (15) | Fianarantsoa | 21,080 | 1,447,296 |

| Vatovavy-Fitovinany (16) | Fianarantsoa | 19,605 | 1,435,882 |

| Atsimo-Atsinanana (17) | Fianarantsoa | 18,863 | 1,026,674 |

| Ihorombe (18) | Fianarantsoa | 26,391 | 418,520 |

| Menabe (19) | Toliara | 46,121 | 700,577 |

| Atsimo-Andrefana (20) | Toliara | 66,236 | 1,799,088 |

| Androy (21) | Toliara | 19,317 | 903,376 |

| Anosy (22) | Toliara | 25,731 | 809,313 |

| Totals | 587,295 | 25,680,342 |

Largest cities and towns

Agriculture has long influenced settlement on the island. Only 15% of the nation's 24,894,551 population live in the 10 largest cities.

United Nations involvement

Madagascar became a Member State of the United Nations on 20 September 1960, shortly after gaining its independence on 26 June 1960.[141] As of January 2017, 34 police officers from Madagascar are deployed in Haiti as part of the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti.[142] Starting in 2015, under the direction of and with assistance from the UN, the World Food Programme started the Madagascar Country Programme with the two main goals of long-term development/ reconstruction efforts and addressing the food insecurity issues in the southern regions of Madagascar.[143] These goals plan to be accomplished by providing meals for specific schools in rural and urban priority areas and by developing national school feeding policies to increase consistency of nourishment throughout the country. Small and local farmers have also been assisted in increasing both the quantity and quality of their production, as well as improving their crop yield in unfavorable weather conditions.[143] In 2017, Madagascar signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[144]

Economy

During the era of Madagascar's First Republic, France heavily influenced Madagascar's economic planning and policy and served as its key trading partner. Key products were cultivated and distributed nationally through producers' and consumers' cooperatives. Government initiatives such as a rural development program and state farms were established to boost production of commodities such as rice, coffee, cattle, silk and palm oil. Popular dissatisfaction over these policies was a key factor in launching the socialist-Marxist Second Republic, in which the formerly private bank and insurance industries were nationalized; state monopolies were established for such industries as textiles, cotton and power; and import–export trade and shipping were brought under state control. Madagascar's economy quickly deteriorated as exports fell, industrial production dropped by 75 percent, inflation spiked and government debt increased; the rural population was soon reduced to living at subsistence levels. Over 50 percent of the nation's export revenue was spent on debt servicing.[24]

The IMF forced Madagascar's government to accept structural adjustment policies and liberalization of the economy when the state became bankrupt in 1982 and state-controlled industries were gradually privatized over the course of the 1980s. The political crisis of 1991 led to the suspension of IMF and World Bank assistance. Conditions for the resumption of aid were not met under Zafy, who tried unsuccessfully to attract other forms of revenue for the State before aid was once again resumed under the interim government established upon Zafy's impeachment. The IMF agreed to write off half Madagascar's debt in 2004 under the Ravalomanana administration. Having met a set of stringent economic, governance and human rights criteria, Madagascar became the first country to benefit from the Millennium Challenge Account in 2005.[19]

Madagascar's GDP in 2015 was estimated at US$9.98 billion, with a per capita GDP of $411.82.[145][146] Approximately 69 percent of the population lives below the national poverty line threshold of one dollar per day.[147] During 2011–15, the average growth rate was 2.6% but was expected to have reached 4.1% in 2016, due to public works programs and a growth of the service sector.[148] The agriculture sector constituted 29 percent of Malagasy GDP in 2011, while manufacturing formed 15 percent of GDP. Madagascar's other sources of growth are tourism, agriculture and the extractive industries.[149] Tourism focuses on the niche eco-tourism market, capitalizing on Madagascar's unique biodiversity, unspoiled natural habitats, national parks and lemur species.[150] An estimated 365,000 tourists visited Madagascar in 2008, but the sector declined during the political crisis with 180,000 tourists visiting in 2010.[149] However, the sector has been growing steadily for a few years; In 2016, 293,000 tourists landed in the African island with an increase of 20% compared to 2015; For 2017 the country has the goal of reaching 366,000 visitors, while for 2018 government estimates are expected to reach 500,000 annual tourists.[151]

The island is still a very poor country in 2018; structural brakes remain in the development of the economy: corruption and the shackles of the public administration, lack of legal certainty, and backwardness of land legislation. The economy, however, has been growing since 2011, with GDP growth exceeding 4% per year;[152][153] almost all economic indicators are growing, the GDP per capita was around $1600 (PPP) for 2017,[154] one of the lowest in the world, although growing since 2012; unemployment was also cut, which in 2016 was equal to 2.1%[155] with a work force of 13.4 million as of 2017.[156] The main economic resources of Madagascar are tourism, textiles, agriculture, and mining.

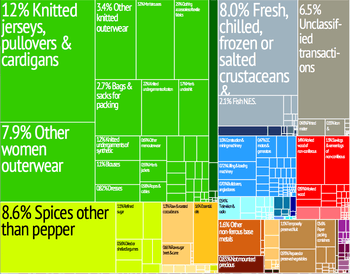

Natural resources and trade

Madagascar's natural resources include a variety of agricultural and mineral products. Agriculture (including the growing of raffia), mining, fishing and forestry are mainstays of the economy. In 2017 the top exports of Madagascar were vanilla (US$894M), nickel metal (US$414M), cloves (US$288M), knitted sweaters (US$184M) and cobalt (US$143M).[158]

Madagascar is the world's principal supplier of vanilla, cloves[159] and ylang-ylang.[26] Madagascar supplies 80% of the world's natural vanilla.[160] Other key agricultural resources include coffee, lychees and shrimp. Key mineral resources include various types of precious and semi-precious stones, and Madagascar currently provides half of the world's supply of sapphires, which were discovered near Ilakaka in the late 1990s.[161]

Madagascar has one of the world's largest reserves of ilmenite (titanium ore), as well as important reserves of chromite, coal, iron, cobalt, copper and nickel.[24] Several major projects are underway in the mining, oil and gas sectors that are anticipated to give a significant boost to the Malagasy economy. These include such projects as ilmenite and zircon mining from heavy mineral sands near Tôlanaro by Rio Tinto,[162] extraction of nickel near Moramanga and its processing near Toamasina by Sherritt International,[163] and the development of the giant onshore heavy oil deposits at Tsimiroro and Bemolanga by Madagascar Oil.[164]

Exports formed 28 percent of GDP in 2009.[19] Most of the country's export revenue is derived from the textiles industry, fish and shellfish, vanilla, cloves and other foodstuffs.[149] France is Madagascar's main trading partner, although the United States, Japan and Germany also have strong economic ties to the country.[24] The Madagascar-U.S. Business Council was formed in May 2003, as a collaboration between USAID and Malagasy artisan producers to support the export of local handicrafts to foreign markets.[165] Imports of such items as foodstuffs, fuel, capital goods, vehicles, consumer goods and electronics consume an estimated 52 percent of GDP. The main sources of Madagascar's imports include China,[166] France, Iran, Mauritius and Hong Kong.[19]

Infrastructure and media

In 2010, Madagascar had approximately 7,617 km (4,730 mi) of paved roads, 854 km (530 mi) of railways and 432 km (270 mi) of navigable waterways.[12] The majority of roads in Madagascar are unpaved, with many becoming impassable in the rainy season. Largely paved national routes connect the six largest regional towns to Antananarivo, with minor paved and unpaved routes providing access to other population centers in each district.[25]

There are several rail lines. Antananarivo is connected to Toamasina, Ambatondrazaka and Antsirabe by rail, and another rail line connects Fianarantsoa to Manakara. The most important seaport in Madagascar is located on the east coast at Toamasina. Ports at Mahajanga and Antsiranana are significantly less used because of their remoteness.[25] The island's newest port at Ehoala, constructed in 2008 and privately managed by Rio Tinto, will come under state control upon completion of the company's mining project near Tôlanaro around 2038.[162] Air Madagascar services the island's many small regional airports, which offer the only practical means of access to many of the more remote regions during rainy season road washouts.[25]

Running water and electricity are supplied at the national level by a government service provider, Jirama, which is unable to service the entire population. As of 2009, only 6.8 percent of Madagascar's fokontany had access to water provided by Jirama, while 9.5 percent had access to its electricity services.[137] Fifty-six percent of Madagascar's power is provided by hydroelectric power plants, with the remaining 44% provided by diesel engine generators.[167] Mobile telephone and internet access are widespread in urban areas but remain limited in rural parts of the island. Approximately 30% of the districts are able to access the nations' several private telecommunications networks via mobile telephones or land lines.[137]

Radio broadcasts remain the principal means by which the Malagasy population access international, national, and local news. Only state radio broadcasts are transmitted across the entire island. Hundreds of public and private stations with local or regional range provide alternatives to state broadcasting.[121] In addition to the state television channel, a variety of privately owned television stations broadcast local and international programming throughout Madagascar. Several media outlets are owned by political partisans or politicians themselves, including the media groups MBS (owned by Ravalomanana) and Viva (owned by Rajoelina),[62] contributing to political polarization in reporting.

The media have historically come under varying degrees of pressure to censor their criticism of the government. Reporters are occasionally threatened or harassed, and media outlets are periodically forced to close.[121] Accusations of media censorship have increased since 2009 because of the alleged intensification of restrictions on political criticism.[128] Access to the internet has grown dramatically over the past decade, with an estimated 352,000 residents of Madagascar accessing the internet from home or in one of the nation's many internet cafés in December 2011.[121]

Health

Medical centers, dispensaries and hospitals are found throughout the island, although they are concentrated in urban areas and particularly in Antananarivo. Access to medical care remains beyond the reach of many Malagasy, especially in the rural areas, and many recourse to traditional healers.[168] In addition to the high expense of medical care relative to the average Malagasy income, the prevalence of trained medical professionals remains extremely low. In 2010, Madagascar had an average of three hospital beds per 10,000 people and a total of 3,150 doctors, 5,661 nurses, 385 community health workers, 175 pharmacists, and 57 dentists for a population of 22 million. Fifteen percent of government spending in 2008 was directed toward the health sector. Approximately 70 percent of spending on health was contributed by the government, while 30 percent originated with international donors and other private sources.[169] The government provides at least one basic health center per commune. Private health centers are concentrated within urban areas and particularly those of the central highlands.[137]

Despite these barriers to access, health services have shown a trend toward improvement over the past twenty years. Child immunizations against such diseases as hepatitis B, diphtheria, and measles increased an average of 60 percent in this period, indicating low but increasing availability of basic medical services and treatments. The Malagasy fertility rate in 2009 was 4.6 children per woman, declining from 6.3 in 1990. Teen pregnancy rates of 14.8 percent in 2011, much higher than the African average, are a contributing factor to rapid population growth.[169] In 2010, the maternal mortality rate was 440 per 100,000 births, compared to 373.1 in 2008 and 484.4 in 1990, indicating a decline in perinatal care following the 2009 coup. The infant mortality rate in 2011 was 41 per 1,000 births,[19] with an under-five mortality rate at 61 per 1,000 births.[170] Schistosomiasis, malaria, and sexually transmitted diseases are common in Madagascar, although infection rates of AIDS remain low relative to many countries in mainland Africa, at 0.2 percent of the adult population. The malaria mortality rate is also among the lowest in Africa at 8.5 deaths per 100,000 people, in part because of the highest frequency use of insecticide treated nets in Africa.[169] Adult life expectancy in 2009 was 63 years for men and 67 years for women.[169]

Madagascar had outbreaks of the bubonic plague and pneumonic plague in 2017 (2575 cases, 221 deaths) and 2014 (263 confirmed cases, 71 deaths).[171] In 2019, Madagascar had a measles outbreak, resulting in 118,000 cases and 1,688 deaths. In 2020, Madagascar was also affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Education

_Madagascar.jpg)

Prior to the 19th century, all education in Madagascar was informal and typically served to teach practical skills as well as social and cultural values, including respect for ancestors and elders.[25] The first formal European-style school was established in 1818 at Toamasina by members of the London Missionary Society (LMS). The LMS was invited by King Radama I to expand its schools throughout Imerina to teach basic literacy and numeracy to aristocratic children. The schools were closed by Ranavalona I in 1835[172] but reopened and expanded in the decades after her death.

By the end of the 19th century, Madagascar had the most developed and modern school system in pre-colonial Sub-Saharan Africa. Access to schooling was expanded in coastal areas during the colonial period, with French language and basic work skills becoming the focus of the curriculum. During the post-colonial First Republic, a continued reliance on French nationals as teachers, and French as the language of instruction, displeased those desiring a complete separation from the former colonial power.[25] Consequently, under the socialist Second Republic, French instructors and other nationals were expelled, Malagasy was declared the language of instruction, and a large cadre of young Malagasy were rapidly trained to teach at remote rural schools under the mandatory two-year national service policy.[173]

This policy, known as malgachization, coincided with a severe economic downturn and a dramatic decline in the quality of education. Those schooled during this period generally failed to master the French language or many other subjects and struggled to find employment, forcing many to take low-paying jobs in the informal or black market that mired them in deepening poverty. Excepting the brief presidency of Albert Zafy, from 1992 to 1996, Ratsiraka remained in power from 1975 to 2001 and failed to achieve significant improvements in education throughout his tenure.[174]

Education was prioritized under the Ravalomanana administration (2002–09), and is currently free and compulsory from ages 6 to 13.[175] The primary schooling cycle is five years, followed by four years at the lower secondary level and three years at the upper secondary level.[25] During Ravalomanana's first term, thousands of new primary schools and additional classrooms were constructed, older buildings were renovated, and tens of thousands of new primary teachers were recruited and trained. Primary school fees were eliminated, and kits containing basic school supplies were distributed to primary students.[175]

Government school construction initiatives have ensured at least one primary school per fokontany and one lower secondary school within each commune. At least one upper secondary school is located in each of the larger urban centers.[137] The three branches of the national public university are located at Antananarivo, Mahajanga, and Fianarantsoa. These are complemented by public teacher-training colleges and several private universities and technical colleges.[25]

As a result of increased educational access, enrollment rates more than doubled between 1996 and 2006. However, education quality is weak, producing high rates of grade repetition and dropout.[175] Education policy in Ravalomanana's second term focused on quality issues, including an increase in minimum education standards for the recruitment of primary teachers from a middle school leaving certificate (BEPC) to a high school leaving certificate (BAC), and a reformed teacher training program to support the transition from traditional didactic instruction to student-centered teaching methods to boost student learning and participation in the classroom.[176] Public expenditure on education was 2.8 percent of GDP in 2014. The literacy rate is estimated at 64.7%.[20]

Demographics

In 2018, the population of Madagascar was estimated at 26 million, up from 2.2 million in 1900.[7][8][25] The annual population growth rate in Madagascar was approximately 2.9 percent in 2009.[19]

Approximately 42.5 percent of the population is younger than 15 years of age, while 54.5 percent are between the ages of 15 and 64. Those aged 65 and older form 3 percent of the total population.[149] Only two general censuses, in 1975 and 1993, have been carried out after independence. The most densely populated regions of the island are the eastern highlands and the eastern coast, contrasting most dramatically with the sparsely populated western plains.[25]

Ethnic groups

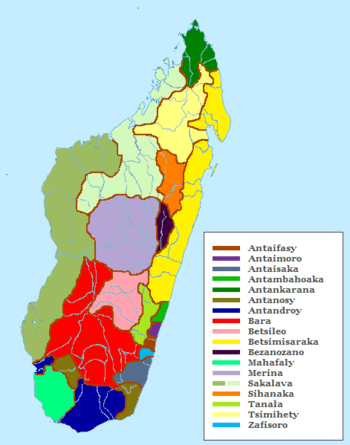

The Malagasy ethnic group forms over 90 percent of Madagascar's population and is typically divided into 18 ethnic subgroups.[19] Recent DNA research revealed that the genetic makeup of the average Malagasy person constitutes an approximately equal blend of Southeast Asian and East African genes,[177][178] although the genetics of some communities show a predominance of Southeast Asian or East African origins or some Arab, Indian, or European ancestry.[179]

Southeast Asian features – specifically from the southern part of Borneo – are most predominant among the Merina of the central highlands,[125] who form the largest Malagasy ethnic subgroup at approximately 26 percent of the population, while certain communities among the coastal peoples (collectively called côtiers) have relatively stronger East African features. The largest coastal ethnic subgroups are the Betsimisaraka (14.9 percent) and the Tsimihety and Sakalava (6 percent each).[25]

| Malagasy ethnic subgroups | Regional concentration |

|---|---|

| Antankarana, Sakalava, Tsimihety | Former Antsiranana Province |

| Sakalava, Vezo | Former Mahajanga Province |

| Betsimisaraka, Sihanaka, Bezanozano | Former Toamasina Province |

| Merina | Former Antananarivo Province |

| Betsileo, Antaifasy, Antambahoaka, Antaimoro, Antaisaka, Tanala | Former Fianarantsoa Province |

| Mahafaly, Antandroy, Antanosy people, Bara, Vezo | Former Toliara Province |

Chinese, Indian and Comoran minorities are present in Madagascar, as well as a small European (primarily French) populace. Emigration in the late 20th century has reduced these minority populations, occasionally in abrupt waves, such as the exodus of Comorans in 1976, following anti-Comoran riots in Mahajanga.[25] By comparison, there has been no significant emigration of Malagasy peoples.[24] The number of Europeans has declined since independence, reduced from 68,430 in 1958[114] to 17,000 three decades later. There were an estimated 25,000 Comorans, 18,000 Indians, and 9,000 Chinese living in Madagascar in the mid-1980s.[25]

Languages

.jpg)

The Malagasy language is of Malayo-Polynesian origin and is generally spoken throughout the island. The numerous dialects of Malagasy, which are generally mutually intelligible,[180] can be clustered under one of two subgroups: eastern Malagasy, spoken along the eastern forests and highlands including the Merina dialect of Antananarivo, and western Malagasy, spoken across the western coastal plains. The Malagasy language originated from Southeast Barito language, and Ma'anyan language is its closest relative, with numerous Malay and Javanese loanwords.[181][182] French became the official language during the colonial period, when Madagascar came under the authority of France. In the first national Constitution of 1958, Malagasy and French were named the official languages of the Malagasy Republic. Madagascar is a francophone country, and French is mostly spoken as a second language among the educated population and used for international communication.[25]

No official languages were mentioned in the Constitution of 1992, although Malagasy was identified as the national language. Nonetheless, many sources still claimed that Malagasy and French were official languages, eventually leading a citizen to initiate a legal case against the state in April 2000, on the grounds that the publication of official documents only in the French language was unconstitutional. The High Constitutional Court observed in its decision that, in the absence of a language law, French still had the character of an official language.[183]

In the Constitution of 2007, Malagasy remained the national language while official languages were reintroduced: Malagasy, French, and English.[184] English was removed as an official language from the constitution approved by voters in the November 2010 referendum.[1] The outcome of the referendum, and its consequences for official and national language policy, are not recognized by the political opposition, who cite lack of transparency and inclusiveness in the way the election was organized by the High Transitional Authority.[117]

Religion

Religion in Madagascar (2010) according to the Pew Research Center[3]

According to the U.S. Department of State in 2011, 41% of Madagascans practiced Christianity, and 52% adhered to traditional religions,[19] which tends to emphasize links between the living and the razana (ancestors); these numbers were drawn from the 1993 census. According to the Pew Research Center in 2010, 85% of the population now practiced Christianity, while just 4.5% of Madagascans practiced folk religions; among Christians, practitioners of Protestantism outnumbered adherents of Roman Catholicism.[3]

The veneration of ancestors has led to the widespread tradition of tomb building, as well as the highlands practice of the famadihana, whereby a deceased family member's remains are exhumed and re-wrapped in fresh silk shrouds, before being replaced in the tomb. The famadihana is an occasion to celebrate the beloved ancestor's memory, reunite with family and community, and enjoy a festive atmosphere. Residents of surrounding villages are often invited to attend the party, where food and rum are typically served, and a hiragasy troupe or other musical entertainment is commonly present.[185] Consideration for ancestors is also demonstrated through adherence to fady, taboos that are respected during and after the lifetime of the person who establishes them. It is widely believed that by showing respect for ancestors in these ways, they may intervene on behalf of the living. Conversely, misfortunes are often attributed to ancestors whose memory or wishes have been neglected. The sacrifice of zebu is a traditional method used to appease or honor the ancestors. In addition, the Malagasy traditionally believe in a creator god, called Zanahary or Andriamanitra.[186]

Today, many Christians integrate their religious beliefs with traditional ones related to honoring the ancestors. For instance, they may bless their dead at church before proceeding with traditional burial rites or invite a Christian minister to consecrate a famadihana reburial.[185] The Malagasy Council of Churches comprises the four oldest and most prominent Christian denominations of Madagascar (Roman Catholic, Church of Jesus Christ in Madagascar, Lutheran, and Anglican) and has been an influential force in Malagasy politics.[187]

Islam is also practiced on the island. Islam was first brought to Madagascar in the Middle Ages by Arab and Somali Muslim traders, who established several Islamic schools along the eastern coast. While the use of Arabic script and loan words and the adoption of Islamic astrology would spread across the island, the Islamic religion took hold in only a handful of southeastern coastal communities. Today, Muslims constitute 3–7 percent of the population of Madagascar and are largely concentrated in the northwestern provinces of Mahajanga and Antsiranana. The vast majority of Muslims are Sunni. Muslims are divided between those of Malagasy ethnicity, Indians, Pakistanis and Comorans.

More recently, Hinduism was introduced to Madagascar through Gujarati people immigrating from the Saurashtra region of India in the late 19th century. Most Hindus in Madagascar speak Gujarati or Hindi at home.[188]

Culture

Each of the many ethnic subgroups in Madagascar adhere to their own set of beliefs, practices and ways of life that have historically contributed to their unique identities. However, there are a number of core cultural features that are common throughout the island, creating a strongly unified Malagasy cultural identity. In addition to a common language and shared traditional religious beliefs around a creator god and veneration of the ancestors, the traditional Malagasy worldview is shaped by values that emphasize fihavanana (solidarity), vintana (destiny), tody (karma), and hasina, a sacred life force that traditional communities believe imbues and thereby legitimates authority figures within the community or family. Other cultural elements commonly found throughout the island include the practice of male circumcision; strong kinship ties; a widespread belief in the power of magic, diviners, astrology and witch doctors; and a traditional division of social classes into nobles, commoners, and slaves.[25][186]

Although social castes are no longer legally recognized, ancestral caste affiliation often continues to affect social status, economic opportunity, and roles within the community.[189] Malagasy people traditionally consult Mpanandro ("Makers of the Days") to identify the most auspicious days for important events such as weddings or famadihana, according to a traditional astrological system introduced by Arabs. Similarly, the nobles of many Malagasy communities in the pre-colonial period would commonly employ advisers known as the ombiasy (from olona-be-hasina, "man of much virtue") of the southeastern Antemoro ethnic group, who trace their ancestry back to early Arab settlers.[190]

The diverse origins of Malagasy culture are evident in its tangible expressions. The most emblematic instrument of Madagascar, the valiha, is a bamboo tube zither carried to Madagascar by early settlers from southern Borneo, and is very similar in form to those found in Indonesia and the Philippines today.[191] Traditional houses in Madagascar are likewise similar to those of southern Borneo in terms of symbolism and construction, featuring a rectangular layout with a peaked roof and central support pillar.[192] Reflecting a widespread veneration of the ancestors, tombs are culturally significant in many regions and tend to be built of more durable material, typically stone, and display more elaborate decoration than the houses of the living.[193] The production and weaving of silk can be traced back to the island's earliest settlers, and Madagascar's national dress, the woven lamba, has evolved into a varied and refined art.[194]

The Southeast Asian cultural influence is also evident in Malagasy cuisine, in which rice is consumed at every meal, typically accompanied by one of a variety of flavorful vegetable or meat dishes.[195] African influence is reflected in the sacred importance of zebu cattle and their embodiment of their owner's wealth, traditions originating on the African mainland. Cattle rustling, originally a rite of passage for young men in the plains areas of Madagascar where the largest herds of cattle are kept, has become a dangerous and sometimes deadly criminal enterprise as herdsmen in the southwest attempt to defend their cattle with traditional spears against increasingly armed professional rustlers.[79]

Arts

A wide variety of oral and written literature has developed in Madagascar. One of the island's foremost artistic traditions is its oratory, as expressed in the forms of hainteny (poetry), kabary (public discourse) and ohabolana (proverbs).[196][197] An epic poem exemplifying these traditions, the Ibonia, has been handed down over the centuries in several different forms across the island, and offers insight into the diverse mythologies and beliefs of traditional Malagasy communities.[198] This tradition was continued in the 20th century by such artists as Jean-Joseph Rabearivelo, who is considered Africa's first modern poet,[199] and Elie Rajaonarison, an exemplar of the new wave of Malagasy poetry.[200] Madagascar has also developed a rich musical heritage, embodied in dozens of regional musical genres such as the coastal salegy or highland hiragasy that enliven village gatherings, local dance floors and national airwaves.[201] Madagascar also has a growing culture of classical music fostered through youth academies, organizations and orchestras that promote youth involvement in classical music.

The plastic arts are also widespread throughout the island. In addition to the tradition of silk weaving and lamba production, the weaving of raffia and other local plant materials has been used to create a wide array of practical items such as floor mats, baskets, purses and hats.[165] Wood carving is a highly developed art form, with distinct regional styles evident in the decoration of balcony railings and other architectural elements. Sculptors create a variety of furniture and household goods, aloalo funerary posts, and wooden sculptures, many of which are produced for the tourist market.[202] The decorative and functional woodworking traditions of the Zafimaniry people of the central highlands was inscribed on UNESCO's list of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2008.[203]

Among the Antaimoro people, the production of paper embedded with flowers and other decorative natural materials is a long-established tradition that the community has begun to market to eco-tourists.[202] Embroidery and drawn thread work are done by hand to produce clothing, as well as tablecloths and other home textiles for sale in local crafts markets.[165] A small but growing number of fine art galleries in Antananarivo, and several other urban areas, offer paintings by local artists, and annual art events, such as the Hosotra open-air exhibition in the capital, contribute to the continuing development of fine arts in Madagascar.[204]

Sport

A number of traditional pastimes have emerged in Madagascar. Moraingy, a type of hand-to-hand combat, is a popular spectator sport in coastal regions. It is traditionally practiced by men, but women have recently begun to participate.[205] The wrestling of zebu cattle, which is named savika or tolon-omby, is also practiced in many regions.[206] In addition to sports, a wide variety of games are played. Among the most emblematic is fanorona, a board game widespread throughout the Highland regions. According to folk legend, the succession of King Andrianjaka after his father Ralambo was partially the result of the obsession that Andrianjaka's older brother may have had with playing fanorona to the detriment of his other responsibilities.[207]

Western recreational activities were introduced to Madagascar over the past two centuries. Rugby union is considered the national sport of Madagascar.[208] Soccer is also popular. Madagascar has produced a world champion in pétanque, a French game similar to lawn bowling, which is widely played in urban areas and throughout the Highlands.[209] School athletics programs typically include soccer, track and field, judo, boxing, women's basketball and women's tennis. Madagascar sent its first competitors to the Olympic Games in 1964, and has also competed in the African Games.[24] Scouting is represented in Madagascar by its own local federation of three scouting clubs. Membership in 2011 was estimated at 14,905.[210]