Antaifasy

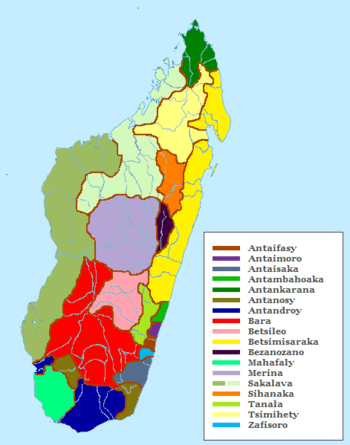

The Antaifasy are an ethnic group of Madagascar inhabiting the southeast coastal region around Farafangana. Historically a fishing and farming people, many Antaifasy were heavily conscripted into forced labor (fanampoana) and brought to Antananarivo as slaves under the 19th century authority of the Kingdom of Imerina. Antaifasy society was historically divided into three groups, each ruled by a king and strongly concentrated around the constraints of traditional moral codes. Approximately 150,000 Antaifasy inhabit Madagascar as of 2013.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 150,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Madagascar | |

| Languages | |

| Malagasy | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Malagasy groups, Austronesian peoples |

History

The origins of the Antaifasy are uncertain.[1] Beginning in the 1680s, the Antaifasy entered into a conflict with the neighboring Antaimoro people. Skirmishes between the clans continued through the 18th century without either clan ever clearly achieving victory over the other. For a short time, the Antaifasy were dominated by the Antaimoro, but were liberated by an Antaifasy king named Maseba. During the 18th century the Antaifasy engaged in coastal trade. Ifara became the most important king during this period by monopolizing trade with European ships, becoming powerful enough to be seen as having control over all trade and travel on the Manampatra river.[2]

In 1827, the Antaifasy kingdom was invaded by the Merina army and made a vassal state of the Kingdom of Imerina in the central highlands.[3] Following years of Antaifasy resistance to Merina rule, Rainivoninahitriniony, later Prime Minister of Madagascar, led another military campaign in 1852 to strengthen Merina authority over the area. During this campaign the Antaifasy fled to an island called Anosinandriamba where they believed they would be safe, but the Merina army crafted rafts out of bamboo to cross the sea and captured the Antaifasy by surprise.[4] In the Merina military conquests between 1820 and 1853, captured Antaifasy men were typically killed, but women and children were often taken as slaves back to Imerina. Over a million slaves were captured during this time, with the majority from the Antaifasy, Antaisaka, Antanosy and Betsileo ethnic groups.[5]

The Antaifasy remained resistant to Merina domination and were never fully subjugated. In an effort to weaken them, the Merina provided support to the Zafisoro, a people who the Antaifasy had previously ruled. Despite French colonization in 1896 and the collapse of the Merina monarchy in 1897, animosity between the two groups has remained and occasionally flared up into violent conflict, as occurred in 1922, 1936 and 1990, resulting in dozens of deaths.[6] During the Malagasy Uprising of 1947, the Malagasy leaders of the resistance movement against French rule (some of whom were aligned with Merina interests) took advantage of the unstable political context to act on old grudges by instigating the Zafisoro to attack the Antaifasy.In the run up to independence from France, two Antefasy brothers founded l'Union Démocratique et Sociale (1957), one of the most successful cross-island political parties. Their representatives took the top position in the Provincial Councils of Tuléar and Fianarantsoa. One of the party's founders, Norbert Zafimahova, was twice elected as president of the Territorial Assembly, delegated to represent Madagascar's interests in the French Senate in 1958.[7][8] Since 1990, this has manifested in competition for control of disputed territory, the most significant being in Farafangana prefecture.[9]

Society

There are approximately 150,000 Antaifasy as of 2013.[10] Their name means "people of the sand." Antaifasy society is traditionally divided into three clans, each governed by its own king:[11] the Randroy, Andrianseranana and Marofela.[1]

Culture

The moral codes that guide Antaifasy social life are very strict.[11]

Traditional clothing among the Antaifasy was made of bark cloth or woven mats of beaten reeds or sedges sewn together. The bark cloth from the Antaifasy region was made from a mix of fibers blended together for sheen and softness and became a specialty trade product of the area. For women, this material was sewn to form a tube that was belted at the waist or pulled up at the shoulder. Women and adolescent girls also often wore a mahampy reed band or short top with or without sleeves, to cover the breasts. Men wore a bark loincloth, and over it they would typically wear a vest or tunic; sleeves were added for older men. Woven hats were also commonly worn by Antaifasy men.[12]

Funeral rites

Like the Antaisaka, the Antaifasy do not bury their dead but instead place them in a kibory funeral house located in a sacred and distant patch of forest.[13]

Language

The Antaifasy speak a dialect of the Malagasy language, which is a branch of the Malayo-Polynesian language group derived from the Barito languages, spoken in southern Borneo.

Economy

The cultivation of rice and fishing from freshwater lakes and rivers are traditional sources of livelihoods among the Antaifasy.[11] In recent decades, there has been a large migration of Antaifasy from their coastal homeland to seek employment farther north.[14]

Notes

- Auzias & Labourdette 2013, p. 72.

- Ogot 1999, p. 435.

- Huyghues-Belrose 2001, p. 418.

- Campbell 2012, p. 815.

- Campbell 2013, p. 2.

- Raison-Jourde & Randrianja 2002, p. 25.

- Thompson & Adloff 1965, p. 258.

- Raison-Jourde & Randrianja 2002, p. 328.

- Raison-Jourde & Randrianja 2002, p. 406.

- Diagram Group 2013.

- Bradt & Austin 2007, p. 24.

- Condra 2013, p. 458.

- Bradt & Austin 2007, p. 23.

- Olson 1996, p. 31.

References

- Auzias, Dominique; Labourdette, Jean-Paul (2013). Madagascar 2014-2015 (in French). Paris: Petit Futé. ISBN 2746969726.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bradt, Hilary; Austin, Daniel (2007). Madagascar (9th ed.). Guilford, CT: The Globe Pequot Press Inc. ISBN 1-84162-197-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, Gwyn (2013). Abolition and Its Aftermath in the Indian Ocean, Africa and Asia. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-77078-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, Gwyn (2012). David Griffiths and the Missionary "History of Madagascar". Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-19518-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Condra, Jill (2013). Encyclopedia of National Dress: Traditional Clothing Around the World. Los Angeles: ABC Clio. ISBN 978-0-313-37637-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Diagram Group (2013). Encyclopedia of African Peoples. San Francisco, CA: Routledge. ISBN 9781135963415.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Huyghues-Belrose, Vincent (2001). Les premiers missionnaires protestants de Masdagascar, (1795-1827) (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 2845861338.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ogot, Bethwell (1999). Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-0-85255-095-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Olson, James (1996). The Peoples of Africa: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Westport CT: Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 978-0-313-27918-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Raison-Jourde, Françoise; Randrianja, Solofo (2002). La nation malgache au défi de l'ethnicité (in French). Paris: Karthala. ISBN 978-2-84586-304-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)