Redshirts (Italy)

Redshirts (Italian Camicie Rosse) or Red coats (Italian Giubbe Rosse) is the name given to the volunteers who followed the Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi during campaigns in Uruguay and Italy, and later his son Ricciotti in Greece and the Balkans, from the 1840s to the 1910s. The name derived from the color of their shirts or loose fitting blouses that the volunteers, usually called Garibaldini, wore in lieu of a uniform.

The force originated as the Italian Legion supporting the Colorado Party during the Uruguayan Civil War, with Garibaldi being given red shirts destined for slaughterhouse workers. Later, during the Italian unification, the Redshirts won several battles against the armies of the Austrian Empire, the Kingdom of Two Sicilies and the Papal States; most notably, Garibaldi led his Redshirts in the Expedition of the Thousand of 1860, which concluded with the annexation of Sicily, Southern Italy, Marche and Umbria to the Kingdom of Sardinia, leading to the creation of the newly unified Kingdom of Italy. Due to his military enterprises in South America and Europe, Garibaldi became known as the "Hero of the Two Worlds".[1] Garibaldi's son Ricciotti led some Redshirt volunteers that fought with the army of Greece during the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 and the First Balkan War.

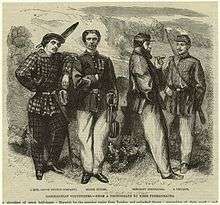

The Redshirts were very popular and influenced many armies worldwide. For example, during the American Civil War, the Garibaldi Guard and their Confederate counterpart Garibaldi Legion, wore red shirts as a part of their uniforms. The Garibaldi shirt also became a popular type of clothing; according to A Cultural History of the Modern Age: The Crisis of the European Soul: "For a considerable time Garibaldi was the most famous man in Europe, and the red shirt, la camicia rossa, became the fashion for ladies, even outside Italy".[2]

Background

The red shirts were started by Giuseppe Garibaldi. During his years of exile, Garibaldi was involved in a military action in Uruguay, where, in 1843, he originally used red shirts from a stock destined for slaughterhouse workers in Buenos Aires. Later, he spent time in private retirement in New York City. Both places have been claimed as the birthplace of the Garibaldian red shirt.[3]

The formation of his force of volunteers in Uruguay, his mastery of the techniques of guerilla warfare, his opposition to the Emperor of Brazil and Argentine territorial ambitions (perceived by liberals as also imperialist), and his victories in the battles of Cerro and Sant'Antonio in 1846 that assured the independence of Uruguay, made Garibaldi and his followers heroes in Italy and Europe. Garibaldi was later hailed as the "Gran Chico Fornido" on the basis of these exploits.

In Uruguay, calling on the Italians of Montevideo, Garibaldi formed the Italian Legion in 1843. In later years, it was claimed that in Uruguay the legion first sported the red shirts associated with Garibaldi's "Thousand", which were said to have been obtained from a factory in Montevideo which had intended to export them to the slaughter houses of Argentina. Red shirts sported by Argentinian butchers in the 1840s are not otherwise documented, however, and the famous camicie rosse did not appear during Garibaldi's efforts in Rome in 1849–50.

Later, after the failure of the campaign for Rome, Garibaldi spent a few years, circa 1850–53, with the Italian patriot and inventor, Antonio Meucci, in a modest gothic frame house (now designated a New York City Landmark), on Staten Island, New York City, before sailing for Italy in 1853. There is a Garibaldi-Meucci museum on Staten Island.

In New York, during the pre-Civil War era, rival companies of volunteer firemen were the great working-class heroes of the city. Their courage, their civic spirit, and the lively comradeship they demonstrated inspired fanatic followers throughout New York, the original "fire buffs".

Volunteer fire companies varied in the completeness and details of their uniforms, but they all wore the red flannel shirt. When Garibaldi returned to Italy after his New York stay, the red shirts made their first appearance among his followers.

Garibaldi remained a local hero among European immigrants back in New York. The "Garibaldi Guard" (39th New York State Volunteers) fought in the American Civil War, 1861–65. As part of their uniform, they wore red woolen "Garibaldi Shirts" – at least, all enlisted men did. The New York Tribune sized them up:

The officers of the Guard are men who have held important commands in the Hungarian, Italian, and German revolutionary armies. Many of them were in the Sardinian and French armies in the Crimea and in Algeria.

A woman's fashion, the Garibaldi shirt, was begun in 1860 by the Empress Eugénie of France, and the blousy style remained popular for some years, eventually turning into the Victorian shirt waist and modern woman's blouse.[4]

Giuseppe Garibaldi's son, Ricciotti Garibaldi, later led Redshirt volunteer troops that fought with the Hellenic Army in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 and the First Balkan War of 1912–13.

The Redshirts gave inspiration to Mussolini to form the Fascist Blackshirts (MVSN) units and, from there, to Hitler's brownshirted Sturmabteilung (SA) units, as well as, the quasi-fascist Irish Blueshirts, under Eoin O'Duffy. However, whilst being vaguely nationalistic in tone, Garibaldi and his men are not widely considered as having been protofascist. Nottingham Forest FC now proudly wear the Garibaldi red shirts since their inception in 1865.

Gallery

Garibaldian volunteers

Garibaldian volunteers One of Garibaldi's lancers carrying a dispatch

One of Garibaldi's lancers carrying a dispatch Truppa di Garibaldi

Truppa di Garibaldi- Uniforms of the garibaldines at the Museum of the Risorgimento, Milan

Red uniform of the Italian politician, Antonio Fratti, killed in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897

Red uniform of the Italian politician, Antonio Fratti, killed in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897

References

- "Unità d'Italia: Giuseppe Garibaldi, l'eroe dei due mondi". Sapere.it (in Italian).

- Egon Friedell & Allan Janik (2010). A Cultural History of the Modern Age: The Crisis of the European Soul. Transaction Publishers. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- Pécout, Gilles (1999). Il lungo Risorgimento: la nascita dell'Italia contemporanea (1770–1922). Paravia Bruno Mondadori. p. 173. ISBN 9788842493570.

- Young, Julia Ditto, "The Rise of the Shirt Waist", Good Housekeeping, May 1902, pp. 354-357

.jpg)