Stendhal

Marie-Henri Beyle (French: [bɛl]; 23 January 1783 – 23 March 1842), better known by his pen name Stendhal (UK: /ˈstɒ̃dɑːl/, US: /stɛnˈdɑːl, stænˈ-/;[1][2][3] French: [stɛ̃dal, stɑ̃dal]),[lower-alpha 1] was a 19th-century French writer. Best known for the novels Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black, 1830) and La Chartreuse de Parme (The Charterhouse of Parma, 1839), he is highly regarded for the acute analysis of his characters' psychology and considered one of the early and foremost practitioners of realism.

Marie-Henri Beyle | |

|---|---|

Stendhal, by Olof Johan Södermark, 1840 | |

| Born | 23 January 1783 Grenoble, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 23 March 1842 (aged 59) Paris, July Monarchy |

| Resting place | Cimetière de Montmartre |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Literary movement | Realism |

Life

Born in Grenoble, Isère, he was an unhappy child, disliking his "unimaginative" father and mourning his mother, whom he passionately loved, and who died when he was seven. He spent "the happiest years of his life" at the Beyle country house in Claix near Grenoble. His closest friend was his younger sister, Pauline, with whom he maintained a steady correspondence throughout the first decade of the 19th century.

The military and theatrical worlds of the First French Empire were a revelation to Beyle. He was named an auditor with the Conseil d'État on 3 August 1810, and thereafter took part in the French administration and in the Napoleonic wars in Italy. He travelled extensively in Germany and was part of Napoleon's army in the 1812 invasion of Russia.[5]

Stendhal witnessed the burning of Moscow from just outside the city. He was appointed Commissioner of War Supplies and sent to Smolensk to prepare provisions for the returning army. He crossed the Berezina River by finding a usable ford rather than the overwhelmed pontoon bridge, which probably saved his life and those of his companions. He arrived in Paris in 1813, largely unaware of the general fiasco that the retreat had become.[6] Stendhal became known, during the Russian campaign, for keeping his wits about him, and maintaining his "sang-froid and clear-headedness." He also maintained his daily routine, shaving each day during the retreat from Moscow.[7]

After the 1814 Treaty of Fontainebleau, he left for Italy, where he settled in Milan. He formed a particular attachment to Italy, where he spent much of the remainder of his career, serving as French consul at Trieste and Civitavecchia. His novel The Charterhouse of Parma, written in 52 days, is set in Italy, which he considered a more sincere and passionate country than Restoration France. An aside in that novel, referring to a character who contemplates suicide after being jilted, speaks about his attitude towards his home country: "To make this course of action clear to my French readers, I must explain that in Italy, a country very far away from us, people are still driven to despair by love."

Stendhal identified with the nascent liberalism and his sojourn in Italy convinced him that Romanticism was essentially the literary counterpart of liberalism in politics.[8] When Stendhal was appointed to a consular post in Trieste in 1830, Metternich refused his exequatur on account of Stendhal's liberalism and anti-clericalism.[9]

Stendhal was a dandy and wit about town in Paris, as well as an obsessive womaniser. His genuine empathy towards women is evident in his books; Simone de Beauvoir spoke highly of him in The Second Sex. One of his early works is On Love, a rational analysis of romantic passion that was based on his unrequited love for Mathilde, Countess Dembowska, whom he met while living at Milan. This fusion of, and tension between, clear-headed analysis and romantic feeling is typical of Stendhal's great novels; he could be considered a Romantic realist.

Stendhal suffered miserable physical disabilities in his final years as he continued to produce some of his most famous work. As he noted in his journal, he was taking iodide of potassium and quicksilver to treat his syphilis, resulting in swollen armpits, difficulty swallowing, pains in his shrunken testicles, sleeplessness, giddiness, roaring in the ears, racing pulse and "tremors so bad he could scarcely hold a fork or a pen". Modern medicine has shown that his health problems were more attributable to his treatment than to his syphilis.

Stendhal died on 23 March 1842, a few hours after collapsing with a seizure on the streets of Paris. He is interred in the Cimetière de Montmartre.

Pseudonyms

Before settling on the pen name Stendhal, he published under many pen names, including "Louis Alexandre Bombet" and "Anastasius Serpière". The only book that Stendhal published under his own name was The History of Painting (1817). From the publication of Rome, Naples, Florence (September 1817) onwards, he published his works under the pseudonym "M. de Stendhal, officier de cavalerie". He borrowed this nom de plume from the German city of Stendal, birthplace of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, an art historian and archaeologist famous at the time.[10]

In 1807 Stendhal stayed near Stendal, where he fell in love with a woman named Wilhelmine, whom he called Minette, and for whose sake he remained in the city. "I have no inclination, now, except for Minette, for this blonde and charming Minette, this soul of the north, such as I have never seen in France or Italy."[10] Stendhal added an additional "H" to make more clear the Germanic pronunciation.

Stendhal used many aliases in his autobiographical writings and correspondence, and often assigned pseudonyms to friends, some of whom adopted the names for themselves. Stendhal used more than a hundred pseudonyms, which were astonishingly diverse. Some he used no more than once, while others he returned to throughout his life. "Dominique" and "Salviati" served as intimate pet names. He coins comic names "that make him even more bourgeois than he really is: Cotonnet, Bombet, Chamier."[11]:80 He uses many ridiculous names: "Don phlegm", "Giorgio Vasari", "William Crocodile", "Poverino", "Baron de Cutendre". One of his correspondents, Prosper Mérimée, said: "He never wrote a letter without signing a false name."[12]

Stendhal's Journal and autobiographical writings include many comments on masks and the pleasures of "feeling alive in many versions." "Look upon life as a masked ball," is the advice that Stendhal gives himself in his diary for 1814.[11]:85 In Memoirs of an Egotist he writes: "Will I be believed if I say I'd wear a mask with pleasure and be delighted to change my name?...for me the supreme happiness would be to change into a lanky, blonde German and to walk about like that in Paris."[13]

Works

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

|

| Portals |

|

Contemporary readers did not fully appreciate Stendhal's realistic style during the Romantic period in which he lived. He was not fully appreciated until the beginning of the 20th century. He dedicated his writing to "the Happy Few" (in English in the original). This can be interpreted as a reference to Canto 11 of Lord Byron's Don Juan, which refers to "the thousand happy few" who enjoy high society, or to the "we few, we happy few, we band of brothers" line of William Shakespeare's Henry V, but Stendhal's use more likely refers to The Vicar of Wakefield by Oliver Goldsmith, parts of which he had memorized in the course of teaching himself English.[14]

In The Vicar of Wakefield, "the happy few" refers ironically to the small number of people who read the title character's obscure and pedantic treatise on monogamy.[14] As a literary critic, such as in Racine and Shakespeare, Stendhal championed the Romantic aesthetic by unfavorably comparing the rules and strictures of Jean Racine's classicism to the freer verse and settings of Shakespeare, and supporting the writing of plays in prose.

Today, Stendhal's works attract attention for their irony and psychological and historical dimensions. Stendhal was an avid fan of music, particularly the works of the composers Domenico Cimarosa, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Gioacchino Rossini. He wrote a biography of Rossini, Vie de Rossini (1824), now more valued for its wide-ranging musical criticism than for its historical content.

In his works, Stendhal reprised excerpts appropriated from Giuseppe Carpani, Théophile Frédéric Winckler, Sismondi and others.[15][16][17][18]

Novels

- Armance (1827)

- Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black, 1830)

- Lucien Leuwen (1835, unfinished, published 1894)

- The Pink and the Green (1837, unfinished)

- La Chartreuse de Parme (1839) (The Charterhouse of Parma)

- Lamiel (1839–1842, unfinished, published 1889)

Novellas

- Mina de Vanghel (1830, later published in the Paris periodical La Revue des Deux Mondes)

- Vanina Vanini (1829)

- Italian Chroniques, 1837–1839

- Vittoria Accoramboni

- The Cenci (Les Cenci, 1837)

- The Duchess of Palliano (La Duchesse de Palliano)

- The Abbess of Castro (L'Abbesse de Castro, 1832)

Biography

- A Life of Napoleon (1817–1818, published 1929)

- A Life of Rossini (1824)

Autobiography

Stendhal's brief memoir, Souvenirs d'Égotisme (Memoirs of an Egotist) was published posthumously in 1892. Also published was a more extended autobiographical work, thinly disguised as the Life of Henry Brulard.

- The Life of Henry Brulard (1835–1836, published 1890)

- Souvenirs d'Égotisme (Memoirs of an Egotist, written in 1832 and published in 1892)

- Journal (1801–1817) (The Private Diaries of Stendhal)

Non-fiction

- Rome, Naples et Florence (1817)

- De L'Amour (1822) (On Love)

- Racine et Shakespéare (1823–1835) (Racine and Shakespeare)

His other works include short stories, journalism, travel books (A Roman Journal), a famous collection of essays on Italian painting, and biographies of several prominent figures of his time, including Napoleon, Haydn, Mozart, Rossini and Metastasio.

Crystallization

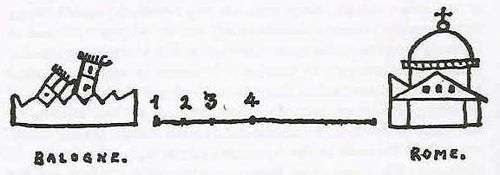

In Stendhal's 1822 classic On Love he describes or compares the "birth of love", in which the love object is 'crystallized' in the mind, as being a process similar or analogous to a trip to Rome. In the analogy, the city of Bologna represents indifference and Rome represents perfect love:

When we are in Bologna, we are entirely indifferent; we are not concerned to admire in any particular way the person with whom we shall perhaps one day be madly in love; even less is our imagination inclined to overrate their worth. In a word, in Bologna "crystallization" has not yet begun. When the journey begins, love departs. One leaves Bologna, climbs the Apennines, and takes the road to Rome. The departure, according to Stendhal, has nothing to do with one's will; it is an instinctive moment. This transformative process actuates in terms of four steps along a journey:

- Admiration – one marvels at the qualities of the loved one.

- Acknowledgement – one acknowledges the pleasantness of having gained the loved one's interest.

- Hope – one envisions gaining the love of the loved one.

- Delight – one delights in overrating the beauty and merit of the person whose love one hopes to win.

This journey or crystallization process (shown above) was detailed by Stendhal on the back of a playing card while speaking to Madame Gherardi, during his trip to the Salzburg salt mine.

Critical appraisal

Hippolyte Taine considered the psychological portraits of Stendhal's characters to be "real, because they are complex, many-sided, particular and original, like living human beings." Émile Zola concurred with Taine's assessment of Stendhal's skills as a "psychologist", and although emphatic in his praise of Stendhal's psychological accuracy and rejection of convention, he deplored the various implausibilities of the novels and Stendhal's clear authorial intervention.[19]

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche refers to Stendhal as "France's last great psychologist" in Beyond Good and Evil (1886).[20] He also mentions Stendhal in the Twilight of the Idols (1889) during a discussion of Dostoevsky as a psychologist, saying that encountering Dostoevsky was "the most beautiful accident of my life, more so than even my discovery of Stendhal".[21]

Ford Madox Ford, in The English Novel, asserts that to Diderot and Stendhal "the Novel owes its next great step forward...At that point it became suddenly evident that the Novel as such was capable of being regarded as a means of profoundly serious and many-sided discussion and therefore as a medium of profoundly serious investigation into the human case."[22]

Erich Auerbach considers modern "serious realism" to have begun with Stendhal and Balzac.[23] In Mimesis, he remarks of a scene in The Red and the Black that "it would be almost incomprehensible without a most accurate and detailed knowledge of the political situation, the social stratification, and the economic circumstances of a perfectly definite historical moment, namely, that in which France found itself just before the July Revolution."[24]

In Auerbach's view, in Stendhal's novels "characters, attitudes, and relationships of the dramatis personæ, then, are very closely connected with contemporary historical circumstances; contemporary political and social conditions are woven into the action in a manner more detailed and more real than had been exhibited in any earlier novel, and indeed in any works of literary art except those expressly purporting to be politico-satirical tracts."[24]

Simone de Beauvoir uses Stendhal as an example of a feminist author. In The Second Sex de Beauvoir writes “Stendhal never describes his heroines as a function of his heroes: he provides them with their own destinies.”[25] She furthermore points out that it “is remarkable that Stendhal is both so profoundly romantic and so decidedly feminist; feminists are usually rational minds that adopt a universal point of view in all things; but it is not only in the name of freedom in general but also in the name of individual happiness that Stendhal calls for women’s emancipation.”[25] Yet, Beauvoir criticises Stendhal for, although wanting a woman to be his equal, her only destiny he envisions for her remains a man.[25]

Even Stendhal's autobiographical works, such as The Life of Henry Brulard or Memoirs of an Egotist, are "far more closely, essentially, and concretely connected with the politics, sociology, and economics of the period than are, for example, the corresponding works of Rousseau or Goethe; one feels that the great events of contemporary history affected Stendhal much more directly than they did the other two; Rousseau did not live to see them, and Goethe had managed to keep aloof from them." Auerbach goes on to say:

We may ask ourselves how it came about that modern consciousness of reality began to find literary form for the first time precisely in Henri Beyle of Grenoble. Beyle-Stendhal was a man of keen intelligence, quick and alive, mentally independent and courageous, but not quite a great figure. His ideas are often forceful and inspired, but they are erratic, arbitrarily advanced, and, despite all their show of boldness, lacking in inward certainty and continuity. There is something unsettled about his whole nature: his fluctuation between realistic candor in general and silly mystification in particulars, between cold self-control, rapturous abandonment to sensual pleasures, and insecure and sometimes sentimental vaingloriousness, is not always easy to put up with; his literary style is very impressive and unmistakably original, but it is short-winded, not uniformly successful, and only seldom wholly takes possession of and fixes the subject. But, such as he was, he offered himself to the moment; circumstances seized him, tossed him about, and laid upon him a unique and unexpected destiny; they formed him so that he was compelled to come to terms with reality in a way which no one had done before him.[24]

Vladimir Nabokov was dismissive of Stendhal, in Strong Opinions calling him "that pet of all those who like their French plain". In the notes to his translation of Eugene Onegin, he asserts that Le Rouge et le Noir is "much overrated", and that Stendhal has a "paltry style". In Pnin Nabokov wrote satirically, "Literary departments still labored under the impression that Stendhal, Galsworthy, Dreiser, and Mann were great writers."[26]

In 2019, rumours began amongst the undergraduate body at the University of Oxford that Stendhal was actually a woman posing as a man. Despite having been reported as such in several essays received by the French Department, this is most likely false.

Michael Dirda considers Stendhal "the greatest all round French writer – author of two of the top 20 French novels, author of a highly original autobiography (Vie de Henry Brulard), a superb travel writer, and as inimitable a presence on the page as any writer you'll ever meet."[27]

Stendhal syndrome

In 1817 Stendhal was reportedly overcome by the cultural richness of Florence he encountered when he first visited the Tuscan city. As he described in his book Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio:

As I emerged from the porch of Santa Croce, I was seized with a fierce palpitation of the heart (that same symptom which, in Berlin, is referred to as an attack of the nerves); the well-spring of life was dried up within me, and I walked in constant fear of falling to the ground.[28]

The condition was diagnosed and named in 1979 by Italian psychiatrist Dr. Graziella Magherini, who had noticed similar psychosomatic conditions (racing heart beat, nausea and dizziness) amongst first-time visitors to the city.

In homage to Stendhal, Trenitalia named their overnight train service from Paris to Venice the Stendhal Express.

See also

Notes

- The pronunciation [stɛ̃dal] is the most common in France today, as shown by the entry stendhalien ([stɛ̃daljɛ̃]) in the Petit Robert dictionary and by the pronunciation recorded on the authoritative website Pronny the pronouncer,[4] which is run by a professor of linguistics and records the pronunciations of highly educated native speakers. The pronunciation [stɑ̃dal] is less common in France today, but was presumably the most common one in 19th-century France and perhaps the one preferred by Stendhal, as shown by the at the time well-known phrase "Stendhal, c'est un scandale" as explained on page 88 of Stendhal: The Red and the Black by Stirling Haig. On the other hand, many obituaries used the spelling Styndal, which clearly indicates that the pronunciation [stɛ̃dal] was also already common at the time of his death (see Literaturblatt für germanische und romanische Philologie (in German). 57 to 58. p. 175). Since Stendhal had lived and traveled extensively in Germany, it is of course also possible that he in fact pronounced his name as the German city [ˈʃtɛndaːl] using /ɛn/ instead of /ɛ̃/ (and perhaps also with /ʃ/ instead of /s/) and that some French speakers approximated this but that most used one of the two common French pronunciations of the spelling -en- ([ɑ̃] and [ɛ̃]).

References

- "Stendhal: definition of Stendhal in Oxford dictionary (British & World English) (US)". Oxforddictionaries.com. 2014-01-23. Retrieved 2014-01-28.

- "Stendhal: definition of Stendhal in Oxford dictionary (American English) (US)". Oxforddictionaries.com. 2014-01-23. Retrieved 2014-01-28.

- "Stendhal - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2014-01-28.

- "Stendhal". Pronny the pronouncer.

- Talty, Stephan. The Illustrious Dead: The Terrifying Story of How Typhus Killed Napoleon's Greatest Army. Three Rivers Press (CA). p. 228. ISBN 9780307394057.

...the novelist Stendhal, an officer in the commissariat, who was still among the luckiest men on the retreat, having preserved his carriage.

- Markham, J. David (April 1997). "Following in the Footsteps of Glory: Stendhal's Napoleonic Career". Napoleonic Scholarship: The Journal of the International Napoleonic Society. 1 (1). Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- Sartre, Jean-Paul (September–October 2009). "War Diary". New Left Review (59). Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- Green, F. C. (2011). Stendhal. Cambridge University Press. p. 158.

- Green, F. C. (2011). Stendhal. Cambridge University Press. p. 239.

- Richardson, Joanna (1974). Stendhal. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan. p. 68.

- Starobinski, Jean (1989). "Pseudononimous Stendhal". The Living Eye. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-53664-9.

- Di Maio, Mariella (2011). "Preface". Aux âmes sensibles, Lettres choisies. Gallimard. p. 19.

- Stendhal (1975). "Chapter V". Memoirs of an Egotist. Translated by Ellis, David. Horizon. pp. 63. ISBN 9780818002243.

- Martin, Brian Joseph. Napoleonic Friendship: Military Fraternity, Intimacy, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century France. UPNE, 2011, p. 123.

- Randall, Marilyn (2001). Pragmatic plagiarism: authorship, profit, and power. University of Toronto Press. p. 199.

If the plagiarisms of Stendhal are legion, many are virtually translations: that is, cross-border plagiarism. Maurevert reports that Goethe, commenting enthusiastically on Stendhal's Rome, Naples et Florence, notes in a letter to a friend: 'he knows very well how to use what one reports to him, and, above all, he knows well how to appropriate foreign works. He translates passages from my Italian Journey and claims to have heard the anecdote recounted by a marchesina.'

- Victor Del Litto in Stendhal (1986) p.500, quote (translation by Randall 2001 p.199): "used the texts of Carpani, Winckler, Sismondi et 'tutti quanti', as an ensemble of materials that he fashioned in his own way. In other words, by isolating his personal contribution, one arrives at the conclusion that the work, far from being a cento, is highly structured such that even the borrowed parts finally melt into a whole a l'allure bien stendhalienne."

- Hazard, Paul (1921). Les plagiats de Stendhal.

- Dousteyssier-Khoze, Catherine; Place-Verghnes, Floriane (2006). Poétiques de la parodie et du pastiche de 1850 à nos jours. p. 34.

- Pearson, Roger (2014). Stendhal: "The Red and the Black" and "The Charterhouse of Parma". Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 0582096162.

- Nietzsche, F., Penguin Classics (1973) p. 187

- Common, Thomas. Twilight of the Idols and The Antichrist. Dover, 2004, p. 46

- Wood, James (2008). How Fiction Works. Macmillan. p. 165. ISBN 9780374173401.

- Wood, Michael (March 5, 2015). "What is concrete?". The London Review of Books. 37 (5): 19–21. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- Auerbach, Erich (May 2003). Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 454–464. ISBN 069111336X.

- De Beauvoir, Simone (1997). The Second Sex. London: Vintage. ISBN 9780099744214.

- Wilson, Edmund (July 15, 1965). "The Strange Case of Pushkin and Nabokov". nybooks.com. The New York Review of Books. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- Dirda, Michael (June 1, 2005). "Dirda on Books". washingtonpost.com. The Washington Post. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- Stendhal. Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio.

Sources

- George Maurevert (1922) Le livre des plagiats

- Stendhal and Del Litto, Victor and Abravanel, Ernest (1986) Oeuvres complètes: Vies de Haydn, de Mozart et de Métastase, volume 41

Further reading

- Blum, Léon, Stendhal et le beylisme, Paris: Paul Ollendorf, 1914.

- Jefferson, Ann. Reading Realism in Stendhal (Cambridge Studies in French), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Dieter, Anna-Lisa, Eros - Wunde - Restauration. Stendhal und die Entstehung des Realismus, Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink, 2019 (Periplous. Münchener Studien zur Literaturwissenschaft).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stendhal. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Stendhal |

| French Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Works by Stendhal at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Stendhal at Internet Archive

- Works by Stendhal at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- StendhalForever.com

- Stendhal's works: text, concordances and frequency list

- (in French) Audio Book (mp3) of The Red and the Black incipit

- (in French) French site on Stendhal

- Centro Stendhaliano di Milano Digital version of Stendhal's shoulder-notes on his own books.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.