Brigandage in Southern Italy after 1861

Brigandage in Southern Italy had existed in some form since ancient times. However its origins as outlaws targeting random travellers would evolve vastly later on in the form of the political resistance movement. During the time of the Napoleonic conquest of the Kingdom of Naples, the first signs of political resistance brigandage came to public light, as the Bourbon loyalists of the country refused to accept the new Bonapartist rulers and actively fought against them until the Bourbon monarchy had been reinstated.[3] Some claim that the word brigandage is a euphemism for what was in fact a civil war.[4]

| Brigantaggio | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Italian Unification | |||||||

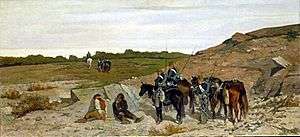

An episode of the Brigantaggio in 1864 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Southern Italian brigands (briganti)

Partisans from Bourbon Spain | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

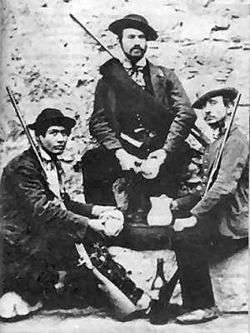

|

Alfonso La Marmora Enrico Cialdini |

Carmine Crocco Ninco Nanco José Borjes | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

(1861–1864) [1][2] 603 killed incl. 21 Officers 253 wounded 24 captured or missing |

(1861–1864) [1][2] 2,413 killed 2,768 captured 1,038 executed | ||||||

History

In the upheaval of Sicily's transition out of feudalism in 1812, and the resulting lack of an effective government police force banditry became a serious problem in much of rural Sicily during the 19th century.[5] Rising food prices, the loss of public and church lands, and the loss of feudal common rights pushed many desperate peasants to banditry.[5][6]

With no police to call upon, local elites in countryside towns recruited young men into "companies-at-arms" to hunt down thieves and negotiate the return of stolen property, in exchange for a pardon for the thieves and a fee from the victims, a development that is often seen as the genesis of the Mafia.[7] These companies-at-arms were often made up of former bandits and criminals, usually the most skilled and violent of them.[6] While this saved communities the trouble of maintaining their own policemen, this may have made the companies-at-arms more inclined to collude with their former brethren rather than destroy them.[6]

After the conquest of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies in 1861 by the Savoyard Kingdom of Sardinia (later Kingdom of Italy), the most famous and well known form of brigandage in the area emerged.[8] According to Marxist theoretician Nicola Zitara, social unrest, especially among the lower classes, occurred due to poor conditions, and the fact that the Risorgimento benefited in the "Mezzogiorno" only the bourgeoisie vast-land owning classes.[3] Many turned to brigandage in the mountains of Basilicata, Campania, Calabria and Abruzzo, but the brigands were not a homogeneous group, nor did they operate with any common cause. Amongst the brigands were a mixture of people, with different working backgrounds and motives; the brigands included former prisoners, bandits and other people who the Italian government regarded as common criminals, but also former soldiers and loyalists of the Bourbon army, as well as foreign mercenaries in the pay of the Bourbon king in exile, some nobles, poverty stricken farmers and peasants who wanted land reforms: both men and women took up arms.[3]

They launched attacks not only against the Italian authorities and the land owning upper-classes, but also against common people[9], frequently looting villages, towns and farms, and committing armed robberies against both individuals and groups, including farmers, townspeople and rival brigand bands.[9] Robberies by brigand bands were often accompanied by other acts of violence and vandalism, such as arsons, murders, rapes, kidnappings, extortions and crop burnings.[9]

In 1863, an extremely strong handed repression of the brigands by the Italian authorities picked up, especially with the passing of the Pica Laws, which permitted the arrest of relatives and those suspected of collaborating or helping a brigand.[10] The villages of Pontelandolfo and Casalduni in the Province of Benevento became the site of a massacre of thirteen brigands by Italian Bersaglieri,[11] conducted as a reprisal following the massacre of forty-five soldiers of the Italian army by local brigands.[12] In total several thousand brigands were arrested and executed, while many more were deported or fled the country (see Italian diaspora).[3] In Palermo in 1866, 40,000 Italian soldiers were needed to put down The Seven and a Half Days Revolt.

After the Italian Unification in 1861, unlike Southern Italy, brigandage was virtually non-existent in the other annexed states of northern and central Italy such as: Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, Duchy of Parma, Duchy of Modena, Grand Duchy of Tuscany, Papal States, because the situation of Southern Italy was very different, owing to the previous centuries of history and the Italian southern historian and politician Francesco Saverio Nitti, describes how brigandage was endemic in Southern Italy already before 1860, using the following words from his book Eroi e briganti (Heroes and brigands),[13] translated into English:

« … every part of Europe has had brigands and criminals, that in war and misfortune time dominated the countryside, and put themselves out of the law […] but there was only one country in Europe where brigandage has existed we can say always […] a country where brigandage for many centuries can look like a huge river of blood and hates […] a country where for centuries monarchy based itself on brigandage, that became like a historical agent: this is the country of Midday » (from Italian “Mezzodì” or “Mezzogiorno” to mean the South of Italy, here referred to XIXth century) .

In relation to the thesis which regards brigandage in southern Italy as a popular revolt against Italian unification or the House of Savoy, it is to be observed that after 1865–1870, when brigandage in the South ended, it was never followed up by any anti-Savoy or anti-unification movement. Many southern Italians held high positions in the new Italian government, such as the 11th Prime Minister of Italy Francesco Crispi. Italians from southern Italy would also go on to play a key role in the ultra-nationalist Fascist movement, most notably the so-called 'philosopher of Fascism' Giovanni Gentile. The thesis which regards the South as hostile to Savoy after the unification also does not explain the fact that with the birth of the Italian Republic, after the referendum of June 2, 1946, the south voted overwhelmingly in favor of the Savoy monarchy, while the north voted for a republic, and from 1946 to 1972 the monarchist parties (which merged into the Italian Democratic Party of Monarchist Unity) gained acclaim especially in the South and in Naples (a city in which nearly 80% supported the Savoy monarchy).[14]

See also

References

- Molfese, Franco (1966). Storia del brigantaggio dopo l'Unità. Milan.

- Monatsschrift zum Conversations-Lexikon (1870). Unsere Zeit. Leipzig.

- "Briganten in Süditalien (i briganti)". Mein-Italien.info. 16 April 2008.

- Finley, Moses I.; Smith, Denis Mack (1968-01-01). A History of Sicily: Modern Sicily, after 1713, by D.M. Smith. (B 68-13584). Chatto & Windus. p. 453.

- Jason Sardell, Economic Origins of the Mafia and Patronage System in Sicily, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, 2009.

- Oriana Bandiera, Private States and the Enforcement of Property Rights: Theory and evidence on the origins of the Sicilian mafia Archived 2012-03-19 at the Wayback Machine, London School of Economics and CEPR, 2001, pp. 8–10

- Lupo, History of the Mafia, p. 34

- Ilaria Porciani, "On the Uses and Abuses of Nationalism from Below: A Few Notes on Italy", in Maarten Van Ginderachter and Marnix Beyen (eds.), Nationhood from Below: Europe in the Long Nineteenth Century (London: Palgrave Macmillan2012), p. 75: "the so-called Brigantaggio (1860–1870)".

- Hilton Wheeler, David (1864). Brigandage in South Italy, by David Hilton Wheeler, Volume 2. London: Sampson Low, Son, and Marston. p. 294.

- "Legge Pica (1863)". Polyarchy.org. 16 April 2008.

- Desiderio, Giancristano (August 8, 2016). "Pontelandolfo, una lettera inedita del 1861: "Perirono 13 persone"". sanniopress.it.

- Sergio Rizzo, Gian Antonio Stella. "Il rogo delle case e 400 morti che nessuno vuole ricordare". www.corriere.it.

- Eroi e briganti (Heroes and brigands) by Francesco Saverio Nitti – (edition 1899) – Osanna Edizioni 2015 – ISBN 8881674696, 9788881674695 – page 33

- Of 1,145,624 valid votes, 903,651 (79%) were monarchist and 241,973 republican (21%)(See page 234 Istat data, in Franco Malnati, La grande frode. Come l'Italia fu fatta Repubblica, Bastogi Collana De Monarchica, Bari, 1998,

- A. Maffei, Brigand Life in Italy: A History of Bourbonist Reaction ca. 1865.

- Lupo, Salvatore (2009). The History of the Mafia, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-13134-6

- New York Times, Brigandage in the Two Sicilies. April 25, 1874.

.jpg)