Duchy of Savoy

From 1416 to 1860, the Duchy of Savoy (Italian: Ducato di Savoia, French: Duché de Savoie) was a country in Western Europe. It was created when Sigismund, King of the Romans, raised the County of Savoy into a duchy for Amadeus VIII. The duchy was an Imperial fief,[1][2][3][4] subject of the Holy Roman Empire with a vote in the Imperial Diet. From the 16th century, Savoy belonged to the Upper Rhenish Circle. Throughout its history, it was ruled by the House of Savoy and formed a part of the larger Savoyard state.

Duchy of Savoy | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1416–1792 1814–1847 | |||||||||||||

Flag of Savoy

Coat of arms of Savoy (16th c.)

| |||||||||||||

Motto: FERT | |||||||||||||

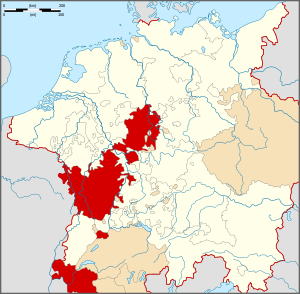

States of the Duke of Savoy around 1700; Savoy proper is in the northwest. | |||||||||||||

| Status | Duchy | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Chambéry (1416–1562) Turin (1562–1847) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Italian, Piedmontese, French, Latin, Francoprovençal, Occitan | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Duchy | ||||||||||||

| Duke | |||||||||||||

• 1416–1440 | Amadeus VIII | ||||||||||||

• 1831–1847 | Charles Albert | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Modern Era | ||||||||||||

| 1416 | |||||||||||||

• Occupied by France | 1536–59, 1630, 1690–96, 1703–13 | ||||||||||||

| 11 April 1713 | |||||||||||||

| 1720 | |||||||||||||

• Occupied by Revolutionary France | 1792–1814 | ||||||||||||

| 29 November 1847 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Italy France Switzerland | ||||||||||||

History

15th century

The Duchy was created in 1416 when Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1433–1437) awarded the title of "Duke" to Count Amadeus VIII.[5][6][7]

Being landlocked at its conception in 1388, the then-County of Savoy acquired a few kilometres of coastline around Nice. Other than this expansion, the 14th century was generally a time of stagnation. Pressure from neighboring powers, particularly France, prevented development, which characterizes the rest of the Renaissance era for Savoy.

The reign of Amadeus VIII was a turning point for the economy and the policy of the state, which deeply marked the history of the nation. His long reign was highlighted by wars (the country expanded its territory by defeating the Duchy of Monferrato and Lordship of Saluzzo), as well as reforms and edicts, and also some controversial actions. The first was in 1434, when he chose to withdraw to the Château de Ripaille, where, living the life of a hermit, he founded the Order of St. Maurice. In 1439, he received an appointment as antipope, which he accepted (under the name of Felix V), although he subsequently resigned a decade later out of a fear of undermining the religious unity of Christians.

The second important action of the Government of Amadeo VIII was the creation of the Principality of Piedmont in August 1424, the management of which was entrusted to the firstborn of the family as a title of honor. The duke left the territory largely formed from the old Savoy domain.

As a cultured and refined man, Duke Amadeus gave great importance to art. Among others, he worked with the famous Giacomo Jaquerio) in literature and architecture, encouraging the entry of art to the Italian Piedmont.

However, his first son Amedeo died prematurely in 1431 and was succeeded by his second son Louis. Louis was in turn succeeded by the weak Amadeus IX, who was extremely religious (he was eventually declared blessed), but of little practical power to the point that he allowed his wife, Yolande (Violante) of Valois, sister of Louis XI, to make very important decisions. During this period, France was more or less free to control the affairs of Savoy, which bound Savoy to the crown in Paris.

The Duchy's economy suffered during these years, not only because of war, but also because of the poor administration by Violante and the continued donations by Amadeus IX to the poor of Vercelli. The future of the nation was entrusted to the hands of a boy, Philibert I, who died at the early age of seventeen, after reigning for ten years. He was succeeded by Charles I, whose ascent to the throne seemed to promise a rebirth of the country.

16th century

When Philibert II died in 1504, he was succeeded by Charles III the Good, a rather weak ruler. Since 1515, Savoy had been occupied by foreign armies, and Francis I of France was just waiting for the opportunity to permanently annex Savoy and its possessions. In 1536, Francis I ordered the occupation of the Duchy, which was invaded by a strong military contingent. Charles III realized too late the weakness of the state, and tried to defend the city of Turin. However, the city was lost on April 3 of the same year. Charles III retired in Vercelli, trying to continue the fight, but never saw the state free from occupation.

Emmanuel Philibert was the Duke who more than any other influenced the future policy of Savoy, managing to put an end to the more than twenty-year long occupation. The Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, signed in 1559, restored full autonomy to the duchy, with his marriage to Margaret of France.[8]

Emmanuel Philibert realized that Savoy could no longer trust France. So he moved the capital to Turin, and which he protected with a complex system of fortifications known as the Cittadella. (Remnants of the Citadalla can still can be seen, although it was largely destroyed by the subsequent expansion of the city.) From his military experience in Flanders, Emmanuel Philibert learned how to run an army, having won the famous Battle of St. Quentin. He was the first Duke of Savoy to establish a stable military apparatus that was not composed of mercenaries but rather by specially trained Savoyan soldiers.

His son, Charles Emmanuel I, extended the duchy to the detriment of the lordships of Monferrato and the territory of Saluzzo, previously ceded to France, in 1601 under the Treaty of Lyon. Unfortunately, the wars of Charles Emmanuel ended mostly in defeats. Nevertheless, he is remembered as "Charles the Great", since he was a versatile and cultured man, a poet and a skillful reformer. He was able to manage the Duchy at a time of severe crisis vis-a-vis the European powers and found support from the Habsburgs. The policy of Charles Emmanuel was in fact based more on actions of international warfare, such as the possessions of the Marquis of Saluzzo, and the wars of succession in the duchies of Mantua and Monferrato. Generally, Savoy sided with Spain, but on occasion allied with France (as, for example, the Treaty of Susa required).

17th century

During the seventeenth century, the influence of the court of Versailles put pressure on Savoy. Due to the proximity of the Duchy of Milan, troops were stationed in France, and the disposal of Pinerolo (one of the most important strongholds of Savoy), were situated close to Turin. The court, which had been under Spanish influence with Charles Emmanuel I, became oriented towards France under his three successors. Vittorio Amedeo I (in office 1630-1637) had married Madame Royale, Maria Christina of Bourbon-France in 1619. Cristina held the real power in Savoy during the short period of the child-duke Francis Hyacinth (reigned 1637-1638) and during the minority (1638-1648) of Charles Emmanuel II.

The strong French influence, plus various misfortunes, repeatedly hit Savoy following the death of Charles Emmanuel I (26 July 1630). First of all, the plague ran rampant in 1630 and contributed significantly to the already widespread poverty.

The Wars of Succession of Monferrato (1628-1631) were very bloody in the countryside and subjected Casale Monferrato to a long siege (1629). Developments of arms and politics affected the economy and future history, exacerbating the already difficult situation after the death of Victor Amadeus I in 1637. He was succeeded for a short period of time by his eldest surviving son, the 5-year-old Francis Hyacinth. The post of regent for the next-oldest son, Carlo Emanuele II, also went to his mother Christine Marie of France, whose followers became known as madamisti (supporters of Madama Reale). Because of this, Savoy became a satellite state of the regent's brother, King Louis XIII of France. The supporters of Cardinal Prince Maurice of Savoy and Prince Thomas Francis of Savoy (both sons of Charles Emmanuel I), together with their followers, took the name of principisti (supporters of the Princes).

Each warring faction soon besieged the city of Turin. The principisti made early gains, making Turin subject to great looting on 27 July 1639. Only in 1642 did the two factions reach an agreement; by now, the widow of Victor Amadeus I had placed Victor's son Charles Emmanuel II on the throne and ruled as regent in his place, even past the child's age of majority.

A resurgence of religious wars took place during the regency. Subsequently, in 1655, Savoyard troops massacred large numbers of the Protestant population of the Waldensian valleys, an event known as the Piedmont Easter (Pasque Piedmont). Eventually international pressure stopped the massacres. A final agreement with the Waldensians was carried out in 1664.

The government of Charles Emmanuel II was the first step towards major reforms carried out by his successor Victor Amadeus II in the next century. Of particular importance were the founding of militias in Savoy and the establishment of the first public school-system in 1661. A cultured man, but also a great statesman, Charles Emmanuel imitated Louis XIV. He wanted to limit this to the court in the sumptuous palace of Venaria Reale, a masterpiece of Baroque architecture, and a copy recreated in Italy of the magnificence of the Palace of Versailles. It was a time of great urban expansion, and Charles Emmanuel II promoted the growth of Turin and its reconstruction in the baroque style. After his death in 1675, there followed the period of the regency (1675-1684) of his widow, the new Madama Reale, Maria Giovanna Battista of Savoy-Nemours.

From duchy to kingdom

The son of Charles Emmanuel II, Victor Amadeus II, was kept under the regency of his mother, the French born Marie Jeanne of Savoy. In the early years of the reign, his energetic mother attempted to unite the crown of Savoy with the Portuguese, and thus risked compromising the very survival of the duchy (Savoy would be reduced like other Italian states to a foreign power). Under the determined hand of the regent Victor Amadeus II, Savoy entered into bad relations with the crown in Paris, which led to the invasion of the duchy by French forces. Savoy defeated the army of Louis XIV in the Siege of Cuneo, but was dramatically defeated in the battles of Staffarda and Marsaglia. Victor Amadeus II married Anne Marie d'Orléans, niece of Louis XIV.

After the War of the Great Alliance, Savoy sided during the first phase of the War of the Spanish Succession alongside Louis XIV. By changing alliances, a new French invasion of Savoy came about, with the troops of the Marquis of Fouillade defeating the troops of Savoy and chasing them into Turin. The event, which succeeded only thanks to the arrival on the battlefield of the duke's cousin, Eugene of Savoy, resolved a conflict that spread destruction in Savoy.

At the end of the war in 1713, Savoy received Sicily, and Victor was awarded the title of King besides the title of Duke of Savoy. According to the treaty of London of 1718, Victor Amadeus II exchanged Sicily for Sardinia in 1720. Sardinia was then changed into the Kingdom of Sardinia. This newly formed country was called States of Savoy or Kingdom of Sardinia, and was composed of several states including Savoy, Piedmont, Aosta Valley, Nice, Oneglia and Sardinia.

After the French Revolution, Savoy was occupied by French Revolutionary forces between 1792 and 1815. The country was first added to the département of Mont-Blanc; then, in 1798, it was divided between the départements of Mont-Blanc and Léman (French name of Lake Geneva). Savoy, Piedmont and Nice were restored to the States of Savoy at the Congress of Vienna in 1814–1815.

In 1860, under the terms of the Treaty of Turin, the Duchy of Savoy was annexed by France. The last Duke of Savoy, Victor Emmanuel II, became King of Italy.

List of Dukes of Savoy

- Amadeus VIII: 1391–1440, duke from 1416

- Louis: 1440–65

- Amadeus IX: 1465–72

- Philibert I: 1472–82

- Charles I: 1482–90, first titular King of Cyprus, Jerusalem and Armenia of the House of Savoy

- Charles (II) John Amadeus: 1490–96

- Philip II: 1496–97

- Philibert II: 1497–1504

- Charles III: 1504–53

- Emmanuel Philibert: 1553–80

- Charles Emmanuel I: 1580–1630

- Victor Amadeus I: 1630–37

- Francis Hyacinth: 1637–38

- Charles Emmanuel II: 1638–75

- Victor Amadeus II: 1675–1730, King of Sicily 1713–1720, then King of Sardinia1

- Charles Emmanuel III: 1730–1773

- Victor Amadeus III: 1773–1796

- Charles Emmanuel IV: 1796–1802

- Victor Emmanuel I: 1802–1821

- Charles Felix of Sardinia: 1821–1831

- Charles Albert of Sardinia: 1831–1849

- Victor Emmanuel II: 1849–1861 (last)

Flag

The flag of Savoy is a white cross on a red field. It is based on a crusader flag, and as such is identical in origin to the flag of the Knights of Malta (whence the modern Flag of Malta and of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta), and others (flags of Denmark and Switzerland, with inverted colors to those of England and Genoa, among others). It was possibly first used by Amadeus III, Count of Savoy, who went on the Second Crusade in 1147. In the 18th century, the letters "FERT" were sometimes added in the cantons to distinguish the flag from the Maltese one.

Notes

- ^ When the Duchy of Savoy acquired Sicily in 1713 and later Sardinia in 1720, the title of "Duke of Savoy", while remaining a primary title, became a lesser title to the title of King. The Duchy of Savoy remained as a state of the new country until the provincial reform of King Charles Albert, at which point the kingdom became a unitary state.

References

- Olaf Asbach, Peter Schröder, The Ashgate Research Companion to the Thirty Years' War, Routledge, 2016, p. 140

- Geoffrey Treasure, Mazarin: The Crisis of Absolutism in France, Psychology Press, 1997, p. 37.

- Derek Croxton, Anuschka Tischer, The Peace of Westphalia, Greenwood Press, 2002, p. 228.

- Daniel Patrick O'Connell, Richelieu, World Publishing Company, 1968, p. 378.

- Hearder 2002, p. 148.

- Oresko 1997, pp. 272, 320.

- Longhi 2015, p. 88.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Henry II, King of France 1547-1559. Duke University Press, 1988. pp. 226-227.

Sources

- Hearder, Harry (2002). Morris, Jonathan (ed.). Italy: A Short History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521000727.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Longhi, Andrea (2015). "Palaces and Palatine Chapels in 15th-Century Italian Dukedoms: Ideas and Experiences". In Beltramo, Silvia; Cantatore, Flavia; Folin, Marco (eds.). A Renaissance Architecture of Power: Princely Palaces in the Italian Quattrocento. Brill. ISBN 978-9004315501.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oresko, Robert (1997). "The House of Savoy in search for a royal crown in the seventeenth century". In Oresko, Robert; Gibbs, G. C.; Scott, H. M. (eds.). Royal and Republican Sovereignty in Early Modern Europe: Essays in Memory of Ragnhild Hatton. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521419109.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)