Karabakh

Karabakh (Armenian: Ղարաբաղ Gharabagh; Azerbaijani: Qarabağ) is a geographic region in present-day eastern Armenia and southwestern Azerbaijan, extending from the highlands of the Lesser Caucasus down to the lowlands between the rivers Kura and Aras.

Karabakh | |

|---|---|

Region | |

A landscape in Nagorno-Karabakh - a view of the municipality of Qırmızı Bazar | |

| Etymology: "Black garden" | |

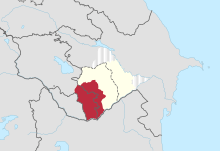

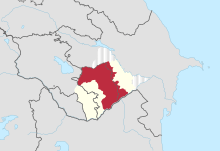

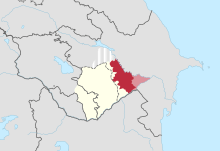

Map of Karabakh within modern borders.

Typical definition of Karabakh.

Maximum historical definition of Karabakh. | |

| Country | Armenia and Azerbaijan |

It is conventionally divided into three regions: Highland Karabakh (historical Artsakh, covered mostly by present-day Nagorno-Karabakh), Lowland Karabakh (the steppes between the Kura and Aras rivers), and the eastern slopes of the Zangezur Mountains (roughly Syunik and Kashatagh).[1][2][3][4][5]

Etymology

The name Karabakh is a Russian transliteration of the local Karabagh, which is generally believed to be a compound of the Turkic word kara (black) and the Iranian word bagh (garden), literally meaning "black garden."[6] However, this has been questioned by some linguists and historians, as black is uncharacteristic of a region "as lush and green" as Karabakh.[7]

According to Iranian linguist Abdolali Karang, kara could have derived from kaleh or kala, which means "large" in the Harzani dialect of the Old Azeri language (pre-Turkic language spoken in Iranian Azerbaijan).[8] The Iranian-Azerbaijani historian Ahmad Kasravi also speaks of the translation of kara as "large" and not "black."[9] The kara prefix has also been used for other nearby regions and landmarks, such as Karadagh (dagh means "mountain") referring to a mountain range, and Karakilise (kilise means "church") referring to the largest church complex in its area, built mainly with white stone. In the sense of "large," Karakilise would translate to "large church," and Karabakh would translate to "large garden."

Another theory, proposed by Armenian historian Bagrat Ulubabyan, is that, along with the "large" translation of kara,[10] the bagh component may have derived from the nearby canton called Baghk, which at some point was part of Armenian principalities within modern-day Karabakh — Dizak and the Kingdom of Syunik (in Baghk, the -k suffix is a plural nominative case marker also used to form names of countries in Old Armenian). In this sense, Karabakh would translate to "Greater Baghk."[11]

The placename is first mentioned in the Georgian Chronicles (Kartlis Tskhovreba), as well in Persian sources from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.[12] The name became common after the 1230s, when the region was conquered by the Mongols.[13] The first time the name was mentioned in medieval Armenian sources was in the fifteenth century, in Tovma Metsop'etsi's History of Tamerlane and His Successors.[12]

Karabagh, an acceptable alternate spelling of Karabakh, denotes a kind of patterned rug originally produced in the area.[14]

Geography

Karabakh is a landlocked region located in the south of Armenia and the west of Azerbaijan. There is currently no official designation for what constitutes the whole of Karabakh. Historically, the maximum extent of what could be considered Karabakh was during the existence of the Karabakh Khanate in the 18th century, which extended from the Zangezur Mountains in the west, following eastwards along the Aras river to the point where it meets with the Kura river in the Kur-Araz Lowland. Following the Kura river north, it stretched as far as what is today the Mingachevir reservoir before turning back to the Zangezur Mountains through the Murov Mountains. However, when not referring to the territory covered by the Karabakh Khanate, the northern regions are often excluded (modern-day Goranboy and Yevlakh). During the Russian Empire, the eastern lowlands where the Kura and Aras rivers meet (mostly modern-day Imishli) were also excluded, but most pre-Elisabethpol maps include that region in Karabakh.

| Zangezur | Highlands or mountainous region | Lowlands or steppe |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Armenia:

Disputed: |

Disputed: | Azerbaijan: |

History

Antiquity

The region today referred to as Karabakh, which was populated with various Caucasian tribes, is believed to have been conquered by the Kingdom of Armenia in the 2nd century BC and organized as parts of the Artsakh, Utik and the southern regions of Syunik provinces. However, it is possible that the region had earlier been part of the Satrapy of Armenia under the Orontid dynasty from as early as the 4th century BC.[15] After the partition of Armenia by Rome and Persia in 387 AD, Artsakh and Utik became a part of the Caucasian Albanian satrapy of Sassanian Persia, while Syunik remained in Armenia.

Middle Ages

The Arab invasions later led to the rise of several Armenian princes who came to establish their dominance in the region.[16] Centuries of constant warfare on the Armenian Plateau forced many Armenians, including those in the Karabakh region, to emigrate and settle elsewhere. During the period of Mongol domination, a great number of Armenians left Lowland Karabakh and sought refuge in the mountainous (Highland) heights of the region.[17]

In the fifteenth century, the German traveler Johann Schiltberger toured Lowland Karabakh and described it as a large and beautiful plain in Armenia, ruled by Muslims.[18] Highland Karabakh from 821 until the early 19th century passed under the hands of a number of states, including the Abbasid Caliphate, Bagratid Armenia, the Mongol Ilkhanate and Jalayirid Sultanates, the Turkic Kara Koyunlu, Ak Koyunlu and Karabakh Baylarbaylik states of the Safavid Empire.[19] Armenian princes times ruled as vassal territories by the Armenian House of Khachen and its several lines, the latter Melikdoms of Karabakh.[16] The Safavids appointed the rulers of Ganja khanate from Ziad-oglu Qajar family to govern Karabakh.[20] It was also invaded and ruled by Ottoman Empire between 1578-1605 and again between 1723-1736, as they briefly conquered it during the Ottoman-Safavid War of 1578-1590 and during the disintegration of Safavid Iran, respectively. In 1747, Panah Javanshir, a local Turkic chieftain, seized control of the region after the death of the Persian ruler Nadir Shah, and both Lower Karabakh and Highland Karabakh comprised the new Karabakh Khanate.[16] The Iranian Qajar dynasty reestablished rule over the region several years later.

Early Modern Age

In 1813, under the terms of the Treaty of Gulistan, the region of Karabakh was lost by the Persians to the Russian Empire. Under Russian rule, Karabakh (both Lowland and Highland) was a region with an area of 13,600 km2 (5,250 sq mi), with Shusha (Shushi) as its most prominent city. Its population consisted of Armenians and Muslims (mainly of "Tatars" (Azerbaijanis), but also Kurds). The Russians conducted a census in 1823 and had tallied the number of villages (though not the number of people) and assessed the tax basis of the entire Karabakh khanate, which also included Lowland Karabakh.[21] It is probable that the Armenians formed the majority of the population of Eastern Armenia at the turn of the seventeenth century,[22] but following Shah Abbas I's massive relocation of Armenians in 1604-05 their numbers decreased markedly, as they eventually became a minority among their Muslim neighbors.

According to the statistics of the initial survey carried out by the Russians in 1823 and an official one published in 1836, Highland Karabakh was found almost overwhelmingly Armenian in population (96.7%).[23] On the other hand, the population of the Karabakh khanate, taken as a whole, was largely made up of Muslims (91% Muslim versus 9% Armenian).[24] A decade after the Russian annexation of the region, many Armenians who had fled Karabakh during the reign of Ibrahim Khalil Khan (1730-1806) and settled in Yerevan, Ganja, and parts of Georgia were repatriated to their villages, many of which had been left derelict.[23] An additional 279 Armenian families were settled in the villages of Ghapan and Meghri in Syunik.[23] Though some of the returning Armenians wished to settle in Karabakh, they were told by Russian authorities that there was no room for them.[23] This took place at the same time as many of the region's Muslims departed for the Ottoman Empire and Qajar Iran.

In 1823, 8.4% of the population of the whole of Karabakh was Armenian[25] who were primarily concentrated in the highlands of Karabakh where they formed 90.8% of the population.[26][27] After the transfer of the Karabakh Khanate to Russia, many Muslim families emigrated to Persia, while many Armenians were induced by the Russian government to immigrate from Persia.[28] Russia's population policy changed the figures, and therefore, Armenian population formed 35% of the population in 1832, and 53% in 1880. Growth of Armenian population in Karabakh is explained with the "increasing migration of Armenians to Mountanious Karabakh or an exodus of Muslims from the region."[24]

The population of Karabakh, according to the official returns of 1832, consisted of 13,965 Muslim and 1,491 Armenian families, besides some Nestorian Christians and Gypsies. The limited population was ascribed to the frequent wars and emigration of many Muslim families to Iran since the region's subjection to Russia, although many Armenians were induced by the Russian government, after the Treaty of Turkmenchay, to emigrate from Persia to Karabakh.[29] The percentage of Armenians accordingly increased to 35% in 1832 and 53% in 1880. These were also seen as consequences of Russo-Turkish wars of 1855-1856 and 1877-1878 because Russians saw the Muslims as unreliable and allies to their ethnically close Turks.[30]

In 1828 the Karabakh khanate was dissolved and in 1840 it was absorbed into the Kaspijskaya (Caspian) oblast, and subsequently, in 1846, made a part of Shemakha Governorate. In 1876 it was made a part of the Elisabethpol Governorate, an administrative arrangement which remained in place until the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917.

Modern Age

Soviet rule

After the dissolution of Russian Empire Karabakh, Zangezur and Nakhchivan were disputed between newly established republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan.[31] Fighting between two republics broke out. Following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, British troops occupied the South Caucasus. The British command affirmed Khosrov bey Sultanov (an appointee of the Azerbaijani government) as the provisional governor-general of Karabakh and Zangezur, pending a final decision by the Paris Peace Conference. But in 1920, Azerbaijan and Armenia were sovietized and Karabakh's status was taken up by the Soviet authorities.[32]

In 1923, parts of Karabakh were made a part of the newly established Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO), an administrative entity of the Azerbaijan SSR, leaving it with a population that was 94% Armenian.[33][34] During the Soviet period, several few attempts were made by the authorities of the Armenian SSR to unite it with the NKAO but these proposals found no support in Moscow.

Nagorno-Karabakh War

In February 1988, within the context of Mikhail Gorbachev's glasnost and perestroika policies, the Supreme Soviet of the NKAO voted to unite itself with Armenia.[35] By the summer of 1989 the Armenian-populated areas of the NKAO were under blockade by Azerbaijan as a response to Armenia's blockade against Nakhichevan, cutting road and rail links to the outside world. On July 12 the Nagorno-Karabakh AO Supreme Soviet voted to secede from Azerbaijan, which was rejected unanimously by the Supreme Soviet of USSR, declaring NKAO had no right to secede from Azerbaijan SSR under Soviet Constitution.[36] Soviet authorities in Moscow then placed the region under its direct rule, installing a special commission to govern the region. In November 1989 the Kremlin returned the oblast to Azerbaijani control. The local government in the region of Shahumian also declared its independence from the Azerbaijan SSR in 1991.[37]

In late 1991, the Armenian representatives in the local government of the NKAO proclaimed the region a republic, independent from Azerbaijan. Portions of the lowland Karabakh are now under the control of the Karabakh Armenian forces. The region's Azerbaijani inhabitants were forced to leave the territories remaining under Armenian control.

Karabakh dialect

The Armenian population of the region speaks the Karabakh dialect of Armenian which has been heavily influenced by the Persian, Russian, and Turkish languages.[38] It was the most extensively spoken of all Armenian dialects until the Soviet period when the dialect of Yerevan became the official tongue of the Armenian SSR.[5]

Flora

The Khari-bulbul (Ophrys caucasica) is a flowering plant endemic to the Karabakh region.[39] Its interesting appearance gives an impression as if a bird, bulbul is sitting on it.

The tulip species Tulipa armena is native to Karabakh.

See also

Notes

- (in Armenian) Leo. Երկերի Ժողովածու [Collected Works]. Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing, 1973, vol. 3, p. 9.

- (in Armenian) Ulubabyan, Bagrat Արցախյան Գոյապայքարը [The Struggle for the Survival of Artsakh]. Yerevan: Gir Grots Publishing, 1994, p. 3. ISBN 5-8079-0869-4.

- Mirza Jamal Javanshir Karabagi. The History of Karabakh. Chapter 2: About the borders, old cities, population aggregates and rivers of the Karabakh region.

- Mirza Jamal Javanshir Karabagi. A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-e Qarabagh, trans. George A. Bournoutian. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishing, 1994, pp. 46ff.

- Hewsen, Robert H. "The Meliks of Eastern Armenia: A Preliminary Study," Revue des Études Arméniennes 9 (1972), p. 289, note 17.

- Regions and territories: Nagorno-Karabakh. BBC News. Accessed August 29, 2009.

- Rouben, Galichian, Historic maps of Armenia : the cartographic heritage, Print info, p. 98, ISBN 9781908755209, OCLC 893915777,

The names do not seem logical, since Karabagh is a lush and green region, [...]

- Karang, Abdolali. Tati va Harzani: Do lahje az zabane bastani-ye Azerbaijan (in Farsi), Tabriz: E. Vaezpour, 1954

- Kasravi, Ahmad. Collection of 78 papers and talks (in Farsi), ed. Yahya Zeka, Lectures, Tehran: Sherkate Sahami Ketabhaye Jibi, 2536, pp. 365/431

- History of the Principality of Khachen, Yerevan, 1975, p. 2

- Hewsen, Robert H. Armenia: a Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001, pp. 119–120.

- (in Armenian) Ulubabyan, Bagrat. «Ղարաբաղ» [Gharabagh]. Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1981, vol. 7, p. 26.

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia, "NKAO, Historical Survey", 3rd edition, translated into English, New York: Macmillan Inc., 1973.

- C. G. Ellis, "Oriental Carpets", 1988. p133.

- Hewsen. Armenia, pp. 118-121.

- Hewsen. Armenia, pp. 119, 155, 163, 264-265.

- Bournoutian, George A. "Review of The Azerbaijani Turks: Power and Identity Under Russian Rule, by Audrey L. Altstadt," Armenian Review 45/2 (Autumn 1992), pp. 63-69.

- Johannes Schiltberger. Bondage and Travels of Johann Schiltberger. Translated by J. Buchan Telfer. Ayer Publishing, 1966, p. 86. ISBN 0-8337-3489-X.

- The Caucasus and Globalization (PDF). 1. Sweden: Institute of Strategic Studies of the Caucasus. 2006. p. 9. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- "Ganja." Encyclopædia Iranica.

- For an English translation see, The 1823 Russian Survey of the Karabagh Province: A Primary Source on the Demography and Economy of Karabagh in the First Half of the 19th Century. Trans. George A. Bournoutian. Costa Mesa, CA, 2011.

- Bournoutian, George A. "Eastern Armenia from the Seventeenth Century to the Russian Annexation," in The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century, ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997, p. 96.

- Bournoutian, George. "The Politics of Demography: Misuse of Sources on the Armenian Population of Mountainous Karabakh." Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies 9 (1996-1997), pp. 99-103.

- Cornell, Svante. Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus. Richmond, Surrey, England: Curzon, 2001, p. 54. ISBN 0-700-71162-7.

- Yazdani, Ahmed Omid (1993). Geteiltes Aserbaidschan: Blick auf ein bedrohtes Volk (German Edition). Das Arabische Buch. p. 88. ISBN 3860930230.

- Description of the Karabakh province prepared in 1823 according to the order of the governor in Georgia Yermolov by state advisor Mogilevsky and colonel Yermolov 2nd (Russian: Opisaniye Karabakhskoy provincii sostavlennoye v 1823 g po rasporyazheniyu glavnoupravlyayushego v Gruzii Yermolova deystvitelnim statskim sovetnikom Mogilevskim i polkovnikom Yermolovim 2-m), Tbilisi, 1866.

- Bournoutian, George A. A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-E Qarabagh. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1994, page 18

- The penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. 1833, Georgia.

- The Penny Encyclopædia [ed. by G. Long] of the Society for the diffusion of useful knowledge. Publication Date: 1833.

- Cornell. Small Nations, p. 54.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. "The Armeno-Azerbaijani Conflict Over Mountainous Karabagh," Armenian Review 24/2 (Summer 1971), pp. 3-39.

- See Hovannisian, Richard G. The Republic of Armenia: The First Year, 1918-1919. Berkeley: University of California, 1971, pp. 162ff, 178–194. ISBN 0-5200-1984-9; idem, The Republic of Armenia: From London to Sevres, February - August 1920, Vol. 3. Berkeley: University of California Press, 131-172. ISBN 0-5200-8803-4.

- Bradshaw, Michael J; George W. White (2004). Contemporary World Regional Geography: Global Connections, Local Voices. New York: Mcgraw-Hill. p. 164. ISBN 0-0725-4975-0.

- Yamskov, A. N. "Ethnic Conflict in the Transcausasus: The Case of Nagorno-Karabakh," Special Issue on Ethnic Conflict in the Soviet Union for the Theory and Society 20 (October 1991), p. 659.

- De Waal, Thomas. Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press, 2003, pp. 10-11.

- "TOP SOVIETS REJECT ARMENIA'S CLAIM AZERBAIJAN KEEPS DISPUTED REGION". Chicago Tribune. 1988-07-19. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- De Waal. Black Garden, p. 85.

- De Waal. Black Garden, p. 186.

- "The Flower of Karabakh". Azerbaijan Center. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

Further reading

Primary sources

- Mirza Jamal Javanshir Karabagi. A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-e Qarabagh. Trans. George A. Bournoutian. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishing, 1994.

- Archbishop Sargis Hasan-Jalaliants. A History of the Land of Artsakh, Karabagh and Genje, 1722-1827. Trans. Ka'ren Ketendjian, with introduction, annotations and notes by Robert H. Hewsen. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishing, 2012.

Secondary sources

- Bournoutian, George. "Rewriting History: Recent Azeri Alterations of Primary Sources Dealing with Karabakh." Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies. 1992, 1993, pp. 185–190.

- De Waal, Thomas. Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press, 2003.

- Hewsen, Robert H. "The Meliks of Eastern Armenia: A Preliminary Study," (serialized in four parts) Revue des Études Arméniennes 9 (1972); 10 (1973/74); 11 (1975/76); 14 (1980).