Vegan nutrition

Vegan nutrition refers to the nutritional and human health aspects of vegan diets. A well-planned, balanced vegan diet is suitable to meet all recommendations for nutrients in every stage of human life.[1] Vegan diets tend to be higher in dietary fiber, magnesium, folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin E, iron, and phytochemicals; and lower in dietary energy, saturated fat, cholesterol, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and vitamin B12.[2] Preliminary evidence from epidemiological research indicates that a vegan diet may lower the risk of cancer.[3]

Background

Vegan diets, compared to standard diets, tend to be higher in dietary fibre, magnesium, folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin E, and iron, and lower in calories, saturated fat, cholesterol, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and vitamin B12.[4] Because plant foods do not provide vitamin B12 (which is produced by microorganisms such as bacteria), researchers agree that those on a vegan diet should eat foods fortified with B12 or take a dietary supplement.[1][5]

Nutrition

The American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (formerly known as the American Dietetic Association), Dietitians of Canada and the British Dietetic Association[6] state that well-planned vegan diets can meet all human nutrient requirements and are appropriate for all stages of life, including during pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence,[1] while the German Society for Nutrition does not recommend vegan diets for children, adolescents, or during pregnancy and breastfeeding.[7] The American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics adds that well-planned vegan diets are also appropriate for older adults and athletes, and that vegan diets may reduce the risk of certain health conditions, such as cancer.[1]

Special attention may be necessary to ensure that a vegan diet will provide adequate amounts of vitamin B12, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, iodine, iron, and zinc.[1] These nutrients may be available in plant foods, with the exception of vitamin B12, which can be obtained only from B12-fortified vegan foods or supplements. Iodine may also require supplementation, such as using iodized salt.[1]

Nutritional deficiencies

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is not made by plants or animals, but by bacteria that grow in soil, feces, dirty water, the intestines of animals or laboratories,[8][9][10][11][12] so plant foods are not reliable sources of B12.[13] The UK Vegan Society, the Vegetarian Resource Group, and the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, among others, recommend that every vegan consume adequate B12 either from fortified foods or by taking a supplement.[14][15][16][17]

Vitamin B12 deficiency is potentially extremely serious, leading to megaloblastic anemia, nerve degeneration and irreversible neurological damage.[18] Because B12 is stored in large amounts in the liver, deficiency in adults may begin only years after adoption of a diet lacking B12. For infants and young children who have not built up these stores, onset of B12 deficiency can be faster and supplementation for vegan children is thus crucial.

Evidence shows that vegans who are not taking vitamin B12 supplements do not consume sufficient B12 and often have abnormally low blood concentrations of vitamin B12.[19] This is because, unless fortified, plant foods do not contain reliable amounts of active vitamin B12. Vegans are advised to adopt one of the following dietary options:[20]

- Consume fortified foods 2-3 times per day to get at least 3 micrograms of vitamin B12,

- or take 10 micrograms of B12 as a supplement once per day

- or take 2000 micrograms of B12 as a supplement once per week

B12 is more efficiently absorbed in small regular doses, which explains why the quantity required rises so quickly as frequency goes down.

The US National Institutes of Health recommends B12 intake in a range from 0.4 micrograms a day for infants, to 2.4 micrograms for adults, and up to 2.8 micrograms for nursing mothers. [21] The European Food Safety Authority set the Adequate Intake at 1.5 micrograms for infants, 4 micrograms for children and adults, and 4.5 and 5 micrograms during pregnancy and nursing.[22] These amounts can be obtained by eating B12 fortified foods, which include some common breakfast cereals, soy milks, and meat analogues, as well as from common multivitamins such as One-A-Day. Some of the fortified foods require only a single serving to provide the recommended B12 amounts. [23]

Other B12 fortified foods may include some almond milks, coconut milks, other plant milks, nutritional yeast, vegan mayonnaise, tofu, and various types and brands of vegan deli slices, burgers, and other veggie meats.

Protein

Upon digestion, all protein foods supply amino acids. Varied intake of plant foods can meet human health needs for protein and amino acids.[1] Foods high in protein in a vegan diet include legumes (such as beans and lentils), nuts, seeds, and grains (such as oats, wheat, and quinoa).[1][24]

Omega-3 fatty acids

Major vegan sources of the essential omega-3 fatty acid ALA include walnuts, flaxseeds and flaxseed oil, canola (rapeseed) oil, algae oil, hempseeds and hempseed oil, olive oil, and avocado.[1]

Diets without seafood are lower in non-essential long-chain omega-3 fatty acids like DHA and EPA. Short-term supplemental ALA has been shown to increase EPA levels, but not DHA levels, suggesting limited conversion of the intermediary EPA to DHA.[25] DHA supplements derived from DHA-rich microalgae are available, and the human body can also convert DHA to EPA.[26] Although omega-3 has previously been thought useful for helping alleviate dementia, as of 2016, there is no good evidence of effectiveness.[27]

While there is little evidence of adverse health or cognitive effects due to DHA deficiency in adult vegetarians or vegans, fetal and breast milk levels remain a concern.[25] EPA and DHA supplementation has been shown to reduce platelet aggregation in vegetarians, but a direct link to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, which is already lower for vegetarians, has yet to be determined.[28]

Calcium

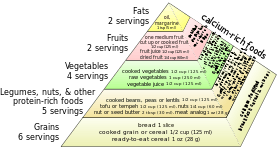

It is recommended that vegans eat three servings per day of a high-calcium food, such as fortified plant milks, green leafy vegetables, seeds, tofu, or other calcium-rich foods, and take a calcium supplement as necessary.[1][29]

Many studies have examined possible correlation between veganism, calcium intake, and bone health. The EPIC-Oxford study suggested that vegans who consumed 525 mg or less of calcium per day have an increased risk of bone fractures over meat eaters and vegetarians, but that vegans consuming more than 525 mg/day had a risk of fractures similar to other groups. Overall, the entire group of vegans had a higher risk of fractures.[30] A 2009 study of bone density found the bone density of vegans was 94 percent that of omnivores, but deemed the difference clinically insignificant.[31] Another study in 2009 by the same researchers examined over 100 vegan post-menopausal women, and found that their diet had no adverse effect on bone mineral density (BMD) and no alteration in body composition.[32] Biochemist T. Colin Campbell suggested in The China Study (2005) that osteoporosis is linked to the consumption of animal protein because, unlike plant protein, animal protein increases the acidity of blood and tissues, which he believed was neutralized by calcium pulled from the bones resulting in hypercalciuria. Campbell wrote that his China-Oxford-Cornell study of nutrition in the 1970s and 1980s found that, in rural China, "where the animal to plant ratio [for protein] was about 10 percent, the fracture rate is only one-fifth that of the U.S."[33]

Calcium is one component of the most common type of human kidney stones, calcium oxalate. Some studies suggest that people who take supplemental calcium have a higher risk of developing kidney stones, and these findings have been used as the basis for setting the recommended daily intake (RDI) for calcium in adults.[34][35][36]

Iodine

One study reported a "potential danger of iodine deficiency disorders due to strict forms of vegetarian nutrition, especially when fruits and vegetables grown in soils with low [iodine] levels are ingested."[37] Vegan diets typically require special attention for iodine, for which the only substantial and reliable vegan sources are sea vegetables, iodized salt and supplements. The iodine content of sea vegetables varies widely and may provide more than the recommended upper limit of iodine intake.[1]

Iron

It is recommended for vegans to eat iron-rich foods and vitamin C daily.[38] In several studies, vegans were not found to suffer from iron-deficiency any more than non-vegans.[39][40][41][42] However, due to the low absorption rate on non-heme iron it is recommended to eat dark leafy greens (and other sources of iron) together with sources of Vitamin C.[43] Iron supplementation should be taken at different times to other supplements with a 2+ valence (chemistry) such as calcium or magnesium, as they inhibit the absorption of iron.[44]

Choline

Due to lack of evidence, no country has published a recommended daily intake for choline, which is a vitamin-like essential nutrient. The Australian, New Zealand, and European Union national nutrition bodies note there have been no reports of choline deficiency in the general population.[45] There are, however, Adequate Intakes such as the European Union's number of 400 mg/day for adults, and the US's number of 425 mg/day for adult non-pregnant women and 550 mg/day for adult men.[46]

Choline deficiency, as created in lab conditions, can lead to health problems such as liver damage, a result of liver cells initiating programmed cell death (apoptosis), as well as an increase in neural tube defects in pregnant women.[47] In a study, 77% of men, 44% of premenopausal women, and 80% of postmenopausal women developed fatty liver or muscle damage due to choline deficiency, showing that subject characteristics regulate the dietary requirement.[48] There is also some evidence that choline is an anti-inflammatory as well, but further studies are needed to confirm/refute findings.[49] It is worth noting that many multivitamins do not contain the Adequate Intake of choline.[50]

Although many animal products, like liver and egg, contain high amounts of choline (355 mg/3 oz and 126 mg/large egg, respectively), wheat germ (172 mg/cup), brussel sprouts (63 mg/cup), and broccoli (62 mg/cup) are also good sources of choline.[47] Other sources include soy lecithin, cauliflower, spinach, firm tofu, kidney beans, quinoa and amaranth.

Vitamin D

The main function of vitamin D in the body is increased absorption of calcium, therefore it is good for the bones. It also connects with receptors in the prostate, the heart, blood vessels, muscles, endocrine glands and others.[51]

Sunlight, fortified foods, and supplements, are the main sources of vitamin D for vegans. Humans produce vitamin D naturally in response to ultraviolet light (UV). Complete cloud cover reduces UV penetration by up to 50%, and outdoor shade reduces UV penetration by 60%. UV light penetrates the skin at wavelengths between 290 and 320 nanometers, where it is then converted into vitamin D3.[52] Vitamin D2 can be obtained from fungi, such as mushrooms exposed to sun or industrial ultraviolet light, offering a vegan choice for dietary or supplemental vitamin D.[53][54]

Although vitamin D3 is produced in small amounts by lichens or algae exposed to sunlight,[55][56] industrial production in commercial quantities is limited, and there are few supplement products as of 2019.[57]

The recommended daily allowance in vitamin D for adults under the age of 70 years old is between 600 and 4,000 IU, and for adults over 70 years old, 800 to 4,000 IU.[58]

Reports on exactly how much vitamin D is produced by exposure to sunlight are wild and varied, across the board.

See also

- Vegetarian nutrition

- Nutrition

- Raw veganism

- Nutritional medicine

- The China Study from 2005

References

- Melina, Vesanto; Craig, Winston; Levin, Susan (1 May 2015). "Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets" (PDF). Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 115 (5): 1970–1980. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.025. ISSN 2212-2672. PMID 27886704. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- Craig, Winston J (May 2009). "Health effects of vegan diets". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 89 (5): 1627S–1633S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736N. PMID 19279075.

Vegan diets are usually higher in dietary fiber, magnesium, folic acid, vitamins C and E, iron, and phytochemicals, and they tend to be lower in calories, saturated fat and cholesterol, long-chain n–3 (omega-3) fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and vitamin B-12. ... A vegan diet appears to be useful for increasing the intake of protective nutrients and phytochemicals and for minimizing the intake of dietary factors implicated in several chronic diseases.

- Dinu, Monica; Abbate, Rosanna; Gensini, Gian Franco; Casini, Alessandro; Sofi, Francesco (6 February 2016). "Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies" (PDF). Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 57 (17): 3640–3649. doi:10.1080/10408398.2016.1138447. hdl:2158/1079985. ISSN 1040-8398. PMID 26853923.

- Craig, Winston J. "Health effects of vegan diets", The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89(5), May 2009, pp. 1627S–1633S (review article).

- Mangels, Reed; Messina, Virginia; and Messina, Mark. "Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin)," The Dietitian's Guide to Vegetarian Diets. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2011, pp. 181–192.

- Mangels, Reed. "Vitamin B12 in the Vegan Diet", Vegetarian Resource Group, accessed December 17, 2012: "Vitamin B12 is needed for cell division and blood formation. Neither plants nor animals make vitamin B12. Bacteria are responsible for producing vitamin B12. Animals get their vitamin B12 from eating foods contaminated with vitamin B12 and then the animal becomes a source of vitamin B12. Plant foods do not contain vitamin B12 except when they are contaminated by microorganisms or have vitamin B12 added to them. Thus, vegans need to look to fortified foods or supplements to get vitamin B12 in their diet."

- "Vitamin B12", Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health, accessed December 17, 2012.

- Norris, Jack. "Vitamin B12: Are you getting it?", Vegan Outreach, July 26, 2006: "Contrary to the many rumors, there are no reliable, unfortified plant sources of vitamin B12 ... [There is an] overwhelming consensus in the mainstream nutrition community, as well as among vegan health professionals, that vitamin B12 fortified foods or supplements are necessary for the optimal health of vegans, and even vegetarians in many cases. Luckily, vitamin B12 is made by bacteria such that it does not need to be obtained from animal products."

- "Vegetarian Diets Food Facts Sheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Richter M, Boeing H, Grünewald-Funk D, Heseker H, Kroke A, Leschik-Bonnet E, Oberritter H, Strohm D, Watzl B for the German Nutrition Society (DGE) (12 April 2016). "Vegan diet. Position of the German Nutrition Society (DGE)" (PDF). Ernahrungs Umschau. 63 (4): 92–102. Erratum in: 63(05): M262. doi:10.4455/eu.2016.021.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Fang H, Kang J, Zhang D (January 2017). "Microbial production of vitamin 12: a review and future perspectives". Microbial Cell Factories. 16 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/s12934-017-0631-y. PMC 5282855. PMID 28137297.

- Moore SJ, Warren MJ (June 2012). "The anaerobic biosynthesis of vitamin B1212". Biochemical Society Transactions. 40 (3): 581–6. doi:10.1042/BST20120066. PMID 22616870.

- Graham RM, Deery E, Warren MJ (2009). "18: Vitamin B12: Biosynthesis of the Corrin Ring". In Warren MJ, Smith AG (eds.). Tetrapyrroles Birth, Life and Death. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. p. 286. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-78518-9_18. ISBN 978-0-387-78518-9.

- Rooke J (October 30, 2013). "Do carnivores need Vitamin B12 supplements?". Baltimore Post Examiner.

- "Vitamin B12". DSM. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- "Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Vitamin B12". National Institutes of Health: Office of Dietary Supplements. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

Strict vegetarians and vegans are at greater risk than lacto-ovo vegetarians and nonvegetarians of developing vitamin B12 deficiency because natural food sources of vitamin B12 are limited to animal foods.

- Watanabe, F. (2007). "Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailability". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 232 (10): 1266–1274. doi:10.3181/0703-MR-67. PMID 17959839.

- Walsh, Stephen. "Vegan Society B12 factsheet". Vegan Society. Archived from the original on May 26, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- Mangels, Reed. "Vitamin B12 in the Vegan Diet". Vegetarian Resource Group. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- "Don't Vegetarians Have Trouble Getting Enough Vitamin B12?". Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- C., Robert; Brown, David (2003-03-01). "Vitamin B12 Deficiency". American Family Physician. 67 (5): 979–986.

- Krajčovičová-Kudláčková, M.; Blažíček, P.; Kopčová, J.; Béderová, A.; Babinská, K. (2000). "Homocysteine Levels in Vegetarians versus Omnivores". Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism. 44 (3): 135–8. doi:10.1159/000012827. PMID 11053901.

- "What Every Vegan Should Know About Vitamin B12". Retrieved 2015-08-05.

- "Vitamin B12: Fact Sheet for Consumers" National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements (retrieved Dec 9, 2016)

- "Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for cobalamin (vitamin B12)" European Food Safety Authority Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies. EFSA Journal 2015;13(7):4150 [64 pp.].

- "Don't Vegetarians Have Trouble Getting Enough Vitamin B12?" Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (retrieved Dec 9, 2016)

- "Plating More Plant-Based Protein". Healthscope Magazine. Retrieved 2015-08-15.

- Sanders, Thomas A.B. (2009). "DHA status of vegetarians". Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids. 81 (2–3): 137–41. doi:10.1016/j.plefa.2009.05.013. PMID 19500961.

- Bouchez, Colette. "Good Fat, Bad Fat: The Facts About Omega-3". WebMD.

- Burckhardt M, Herke M, Wustmann T, Watzke S, Langer G, Fink A (2016). "Omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment of dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Systematic review). 4: CD009002. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009002.pub3. PMC 7117565. PMID 27063583.

- Mezzano, Diego; Kosiel, Karin; Martínez, Carlos; Cuevas, Ada; Panes, Olga; Aranda, Eduardo; Strobel, Pablo; Pérez, Druso D; Pereira, Jaime; et al. (2000). "Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Vegetarians: Normalization of Hyperhomocysteinemia with Vitamin B12 and Reduction of Platelet Aggregation with n-3 Fatty Acids". Thrombosis Research. 100 (3): 153–60. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(00)00313-3. PMID 11108902.

- Craig, Winston J (2009-03-11). "Health effects of vegan diets". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 89 (5): 1627S–1633S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736N. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 19279075.

- Appleby, P; Roddam, A; Allen, N; Key, T (2007). "Comparative fracture risk in vegetarians and nonvegetarians in EPIC-Oxford". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 61 (12): 1400–6. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602659. PMID 17299475.

- Ho-Pham, L. T; Nguyen, N. D; Nguyen, T. V (2009). "Effect of vegetarian diets on bone mineral density: A Bayesian meta-analysis". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 90 (4): 943–50. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27521. PMID 19571226.

- Ho-Pham, L. T.; Nguyen, P. L. T.; Le, T. T. T.; Doan, T. A. T.; Tran, N. T.; Le, T. A.; Nguyen, T. V. (2009). "Veganism, bone mineral density, and body composition: A study in Buddhist nuns". Osteoporosis International. 20 (12): 2087–93. doi:10.1007/s00198-009-0916-z. PMID 19350341.

- Campbell, T. Colin. The China Study. Benbella Books, 2006, pp. 205–208.

- Brody, Jane E. (May 8, 1990). "Huge Study Of Diet Indicts Fat And Meat". The New York Times.

- Junshi, Chen; Campbell, T. Colin; Li; et al., eds. (1990). Diet, lifestyle, and mortality in China: a study of the characteristics of 65 Chinese counties. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-261843-6.

- Byers, Tim (1992-05-15). "Book Reviews: Diet, lifestyle, and mortality in China: a study of the characteristics of 65 Chinese counties". American Journal of Epidemiology. 135 (10): 1180–1. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116219.

- Remer, Thomas; Neubert, Annette; Manz, Friedrich (1999). "Increased risk of iodine deficiency with vegetarian nutrition". British Journal of Nutrition. 81 (1): 45–9. doi:10.1017/s0007114599000136. PMID 10341675.

- "Iron deficiency—adults".

High-risk groups such as vegetarians, adolescent girls and women athletes need to eat iron-rich foods each day (combined with foods that are high in vitamin C). ... Vegetarians who exclude all animal products from their diet may need almost twice as much dietary iron each day as non-vegetarians. Sources include dark green leafy vegetables—such as spinach—and raisins, nuts, seeds, beans, peas, and iron-fortified cereals, breads and pastas

- Larsson, CL; Johansson, GK (2002). "Dietary intake and nutritional status of young vegans and omnivores in Sweden". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 76 (1): 100–6. doi:10.1093/ajcn/76.1.100. PMID 12081822.

- Messina, MJ; Messina, VL (1996). The Dietitian's Guide to Vegetarian Diets: Issues and Applications. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers.

- Craig, WJ (1994). "Iron status of vegetarians". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 59 (5 Suppl): 1233S–1237S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/59.5.1233S. PMID 8172127.

- Ball, MJ; Bartlett, MA (1999). "Dietary intake and iron status of Australian vegetarian women". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 70 (3): 353–8. doi:10.1093/ajcn/70.3.353. PMID 10479197.

- Hallberg, L; Brune, M; Rossander, L (1989). "The role of vitamin C in iron absorption". International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. Supplement. 30: 103–8. PMID 2507689.

The key role of ascorbic acid for the absorption of dietary nonheme iron is generally accepted. The reasons for its action are twofold: (1) the prevention of the formation of insoluble and unabsorbable iron compounds and (2) the reduction of ferric to ferrous iron, which seems to be a requirement for the uptake of iron into the mucosal cells.

- Lönnerdal, B (October 2010). "Calcium and iron absorption--mechanisms and public health relevance". Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 90 (4–5): 293–9. doi:10.1024/0300-9831/a000036. PMID 21462112.

- Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand,

Although choline is essential, there appear to have been no reports of deficiency in the general population. Deficiencies have been seen in experimental situations and also in total parenteral nutrition (Buchman et al. 1992, 1993, 1995, Chalwa et al. 1989, Shapira et al. 1986, Sheard et al. 1986).

- "Choline". Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. 26 September 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- Higdon, Jane (Nov 2003). "Choline". Linus Pauling Institute at Oregon State University. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Fischer, Leslie M.; DaCosta, Kerry A.; Kwock, Lester; Stewart, Paul W.; Lu, Tsui-Shan; Stabler, Sally P.; Allen, Robert H.; Zeisel, Steven H. (May 2007). "Sex and Menopausal Status Influence Human Dietary Requirements for the Nutrient Choline". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 85 (5): 1275–1285. doi:10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1275. PMC 2435503. PMID 17490963.

- Paraskevi, Detopoulou; Panagiotakos, Demosthenes B.; Antonopoulou, Smaragdi; Pitsavos, Christos; Stefanadis, Christodoulos (5 Sep 2007). "Dietary Choline and Betaine Intakes in Relation to Concentrations of Inflammatory Markers in Healthy Adults: The ATTICA Study". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 87 (2): 424–430. doi:10.1093/ajcn/87.2.424. PMID 18258634.

- McCord, BreAnn. "Multivitamins Lack Choline". Beloit College. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Harvard Men's Health Watch (February 2007). "Vitamin D and your health: Breaking old rules, raising new hopes". Harvard MEdical School.

- US National Institute of Health. "Vitamin D Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". US National Institute of Health.

- Haytowitz DB (2009). "Vitamin D in mushrooms" (PDF). Nutrient Data Laboratory, US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Keegan RJ, Lu Z, Bogusz JM, Williams JE, Holick MF (January 2013). "Photobiology of vitamin D in mushrooms and its bioavailability in humans". Dermato-Endocrinology. 5 (1): 165–76. doi:10.4161/derm.23321. PMC 3897585. PMID 24494050.

- Björn, LO; Wang, T (2000). "Vitamin D in an ecological context". International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 59 (1): 26–32. ISSN 1239-9736. PMID 10850004.

- Jäpelt, Rie B.; Jakobsen, Jette (2013). "Vitamin D in plants: a review of occurrence, analysis, and biosynthesis". Frontiers in Plant Science. 4: 136. doi:10.3389/fpls.2013.00136. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC 3651966. PMID 23717318.

- Adi Menayang (29 April 2019). "AIDP: "There is a significant market potential for vegan D3"". NutraIngredients-USA, William Reed, Inc. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Detitians of Canada. "Food Sources of Vitamin D". Dietitians of Canada.