Vasishtha

Vasishtha (Sanskrit: वसीष्ठ, IAST: Vasiṣṭha) is one of the oldest and most revered Vedic rishis.[1][2] He is one of the Saptarishis (seven great Rishis) of India. Vashistha is credited as the chief author of Mandala 7 of Rigveda.[3] Vashishtha and his family are mentioned in Rigvedic verse 10.167.4,[note 1] other Rigvedic mandalas and in many Vedic texts.[6][7][8] His ideas have been influential and he was called as the first sage of the Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy by Adi Shankara.[9]

| Vasishtha | |

|---|---|

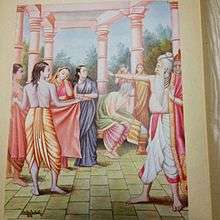

.jpg) Depiction of Vashishtha with his wife Arundhati and Kamadhenu cow | |

| Affiliation | Saptarshi |

| Personal information | |

| Spouse | Arundhati |

| Children | Śakti Maharṣi and hundered other |

Yoga Vashishtha, Vashishtha Samhita, as well as some versions of the Agni Purana[10] and Vishnu Purana are attributed to him. He is the subject of many legends, such as him being in possession of the divine cow Kamadhenu and Nandini her child, who could grant anything to their owners. He is famous in Hindu legends for his legendary conflicts with sage Vishvamitra.[2][11][12] In Ramayana, he was the family priest of Raghu dynasty and teacher of Lord Rama and his brothers.

Etymology

Vashishtha is also spelled as Vasiṣṭha and is Sanskrit for "most excellent, best or richest. According to Monier-Williams, it is sometimes incorrectly spelt as Vashishta or Vashistha (vaśiṣṭha, वशिष्ठ).[13]

History

In Rigvedic hymn 7.33.9, Vashishtha is described as a scholar who moved across the Indus river to establish his school.[14] He was married to Arundhati, and therefore he was also called Arundhati Nath, meaning the husband of Arundhati.[15] Vashishtha is believed to have lived on the banks of Ganga in modern-day Uttarakhand. Later, this region is believed in the Indian tradition to be the abode of sage Vyasa along with Pandavas, the five brothers of Mahabharata.[16] He is typically described in ancient and medieval Hindu texts as a sage with long flowing hairs that are neatly tied into a bun that is coiled with a tuft to the right, a beard, a handlebar moustache and a tilak on his forehead.[17]

In Buddhist Pali canonical texts such as Digha Nikaya, Tevijja Sutta describes a discussion between the Buddha and Vedic scholars of his time. The Buddha names ten rishis, calls them "early sages" and makers of ancient verses that have been collected and chanted in his era, and among those ten rishi is Vasettha (the Pali spelling of Vashishtha in Sanskrit[18]).[19][note 2]

Ideas

Vashishtha is the author of the seventh book of the Rigveda,[3] one of its "family books" and among the oldest layer of hymns in the Vedic scriptures of Hinduism.[20] The hymns composed by Vashishtha are dedicated to Agni, Indra and other gods, but according to RN Dandekar, in a book edited by Michael Witzel, these hymns are particularly significant for four Indravarunau hymns. These have an embedded message of transcending "all thoughts of bigotry", suggesting a realistic approach of mutual "coordination and harmony" between two rival religious ideas by abandoning disputed ideas from each and finding the complementary spiritual core in both.[20] These hymns declare two gods, Indra and Varuna, as equally great. In another hymn, particularly the Rigvedic verse 8.83.9, Vashishtha teaches that the Vedic gods Indra and Varuna are complementary and equally important because one vanquishes the evil by the defeat of enemies in battles, while other sustains the good during peace through socio-ethical laws.[21] The seventh mandala of the Rigveda by Vashishtha is a metaphorical treatise.[22] Vashishtha reappears as a character in Hindu texts, through its history, that explore conciliation between conflicting or opposing ideologies.[23]

According to Ellison Findly – a professor of Religion, Vashishtha hymns in the Rigveda are among the most intriguing in many ways and influential. Vashishtha emphasizes means to be as important as ends during one's life, encouraging truthfulness, devotion, optimism, family life, sharing one's prosperity with other members of society, among other cultural values.[24]

Texts

Practise righteousness (dharma), not unrighteousness.

Speak the truth, not an untruth.

Look at what is distant, not what's near at hand.

Look at the highest, not at what's less than highest.

— Vasishtha Dharmasutra 30.1 [25]

Vasishtha is a revered sage in the Hindu traditions, and like other revered sages, numerous treatises composed in ancient and medieval era are reverentially named after him.[26] Some treatises named after him or attributed to him include:

- Vashishtha samhita is a medieval era Yoga text.[27] There is an Agama as well with the same title.

- Vashishtha dharmasutra, an ancient text, and one of the few Dharma-related treatises which has survived into the modern era. This Dharmasūtra (300–100 BCE) forms an independent text and other parts of the Kalpasūtra, that is Shrauta- and Grihya-sutras are missing.[28] It contains 1,038 sutras.[29]

- Yoga Vashishtha is a syncretic medieval era text that presents Vedanta and Yoga philosophies. It is written in the form of a dialogue between Vashishtha and prince Rama of Ramayana fame, about the nature of life, human suffering, choices as the nature of life, free will, human creative power and spiritual liberation.[30][31] Yoga Vashishtha teachings are structured as stories and fables,[32] with a philosophical foundation similar to those found in Advaita Vedanta.[33][34][35] The text is also notable for its discussion of Yoga.[36][37] According to Christopher Chapple – a professor of Indic studies specializing in Yoga and Indian religions, the Yoga Vashishtha philosophy can be summarized as, "Human effort can be used for self-betterment and that there is no such thing as an external fate imposed by the gods".[38]

- Agni Purana is attributed to Vashishtha.[10]

- Vishnu Purana is attributed to Vashishtha along with Rishi Pulatsya. He has also contributed to many Vedic hymns and is seen as the arranger of Vedas during Dwapara Yuga.

Mythology

According to Agarwal, one mythical legend states that Vashishtha wanted to commit suicide by falling into river Saraswati. But the river prevented this sacrilege by splitting into hundreds of shallow channels. This story, states Agarwal, may have very ancient roots, where "the early man observed the braiding process of the Satluj" and because such a legend could not have invented without the residents observing an ancient river (in Rajasthan) drying up and its tributaries such as Sutlej reflowing to merge into Indus river.[39]

Rivalry with Vishwamitra

Vashishtha is known for his feud with Vishwamitra. The king Vishwamitra coveted Vashistha's divine cow Nandini (Kamadhenu) that could fulfil material desires. Vashishtha destroyed Vishwamitra's army and sons. Vishwamitra acquired weapons from Lord Shiva and incinerated Vashishtha's hermitage and sons, but Vashistha baffled all of Vishwamitra's weapons. Vishwamitra betook severe penances for thousands of years and became a Brahmarshi. He even reconciled with Vashishtha.[40]

Disciples

Vashishtha is best known as the priest and preceptor, teacher of the Ikshvaku kings clan. He was also the preceptor of Manu, the progenitor of Kshatriyas and Ikshvaku's father. Other characters like Nahusha, Rantideva, lord Rama and Bhishma were his disciples.

When the Bharata king Samvarta lost his kingdom to the Panchalas, he became the disciple of Vashistha. Under Vashistha's guidance, Samvarta regained his kingdom and became the ruler of the earth.

The Vashishtha Head

A copper casting of a human head styled in the manner described for Vashishtha was discovered in 1958 in Delhi. This piece has been dated to around 3700 BCE, plus minus 800 years, in three western universities (ETH Zurich, Stanford and UC) using among other methods carbon-14 dating tests, spectrographic analysis, X-ray dispersal analysis and metallography.[17][41] This piece is called "Vashishtha head", because the features, hairstyle, tilak and other features of the casting resembles the description for Vashishtha in Hindu texts.[17]

The significance of "Vasishtha head" is unclear because it was not found at an archaeological site, but in open Delhi market where it was scheduled to be remelted. Further, the head had an inscription of "Narayana" suggesting that the item was produced in a much later millennium. The item, states Edwin Bryant, likely was re-cast and produced from an ancient pre-2800 BCE copper item that left significant traces of matter with the observed C-14 dating.[17]

Vashishtha Temples

There is an Ashram dedicated to Vashishtha in Guwahati, India. This Ashram is situated close to Assam-Meghalaya border to the south of Guwahati city and is a major tourist attraction of Guwahati. Vashishtha's Temple is situated in Vashisht village, Himachal Pradesh. Vashishtha Cave, a cave on the banks of Ganges at Shivpuri, 18 km from Rishikesh is also locally believed to be his winter abode and houses a Shiva temple, also nearby is Arundhati Cave.

Guru Vashishtha is also the primary deity at Arattupuzha Temple known as Arattupuzha Sree Dharmasastha in Arattupuzha village in Thrissur district of Kerala. The famous Arattupuzha Pooram is a yearly celebration where Sri Rama comes from the Thriprayar Temple to pay obeisance to his Guru at Arattupuzha temple.

Notes

- Kasyapa is mentioned in RV 9.114.2, Atri in RV 5.78.4, Bharadvaja in RV 6.25.9, Vishvamitra in RV 10.167.4, Gautama in RV 1.78.1, Jamadagni in RV 3.62.18, etc.;[4] Original Sanskrit text: प्रसूतो भक्षमकरं चरावपि स्तोमं चेमं प्रथमः सूरिरुन्मृजे । सुते सातेन यद्यागमं वां प्रति विश्वामित्रजमदग्नी दमे ॥४॥[5]

- The Buddha names the following as "early sages" of Vedic verses, "Atthaka (either Ashtavakra or Atri), Vamaka, Vamadeva, Vessamitta (Visvamitra), Yamataggi, Angirasa, Bharadvaja, Vasettha (Vashistha), Kassapa (Kashyapa) and Bhagu (Bhrigu)".[19]

References

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 742. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- Mariasusai Dhavamony (1999). Hindu Spirituality. Gregorian. pp. 50 with footnote 63. ISBN 978-88-7652-818-7.

- Stephanie Jamison; Joel Brereton (2014). The Rigveda: 3-Volume Set. Oxford University Press. pp. 1681–1684. ISBN 978-0-19-972078-1.

- Gudrun Bühnemann (1988). Pūjā: A Study in Smārta Ritual. Brill Academic. p. 220. ISBN 978-3-900271-18-3.

- Rigveda 10.167.4, Wikisource

- "according to Rig Veda 7.33:11 he is the son of Maitravarun and Urvashi" Prof. Shrikant Prasoon, Pustak Mahal, 2009, ISBN 8122310729, ISBN 9788122310726.

- Rigveda, translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith,

A form of lustre springing from the lightning wast thou, when Varuṇa and Mitra saw thee;

Tliy one and only birth was then, Vashiṣṭha, when from thy stock Agastya brought thee hither.

Born of their love for Urvasi, Vashiṣṭha thou, priest, art son of Varuṇa and Mitra;

And as a fallen drop, in heavenly fervour, all the Gods laid thee on a lotus-blossom - Maurice Bloomfield (1899). Atharvaveda. K.J. Trübner. pp. 31, 111, 126.

- Chapple, Christopher (1984). "Introduction". The Concise Yoga Vāshiṣṭha. Translated by Venkatesananda, Swami. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. xi. ISBN 0-87395-955-8. OCLC 11044869.

- Horace Hayman Wilson (1840). The Vishńu Puráńa: A System of Hindu Mythology and Tradition. Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. p. xxxvi.

- Horace Hayman Wilson (1840). The Vishńu Puráńa: A System of Hindu Mythology and Tradition. Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. p. lxix.

- Adheesh A. Sathaye (2015). Crossing the Lines of Caste: Vishvamitra and the Construction of Brahmin Power in Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 254–255. ISBN 978-0-19-934111-5.

- Monier-Williams, Monier (1899). "vaśiṣṭha". A Sanskrit-English dictionary : etymologically and philologically arranged with special reference to cognate Indo-European languages. Oxford: Clarendon Press., Archive 2

- Michael Witzel (1997). Inside the Texts, Beyond the Texts: New Approaches to the Study of the Vedas: Proceedings of the International Vedic Workshop, Harvard University, June 1989. Harvard University Press. pp. 289 with footnote 145. ISBN 978-1-888789-03-4.

- Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 70.

- Strauss, Sarah (2002). "The Master's Narrative: Swami Sivananda and the Transnational Production of Yoga". Journal of Folklore Research. Indiana University Press. 23: 221. JSTOR 3814692.

- Edwin Bryant (2003). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-19-516947-8.

- Steven Collins (2001). Aggañña Sutta. Sahitya Akademi. p. 17. ISBN 978-81-260-1298-5.

- Maurice Walshe (2005). The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Digha Nikaya. Simon and Schuster. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-0-86171-979-2.

- Michael Witzel (1997). Inside the Texts, Beyond the Texts: New Approaches to the Study of the Vedas: Proceedings of the International Vedic Workshop, Harvard University, June 1989. Harvard University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-888789-03-4. OCLC 246746415.

- J. C. Heesterman; Albert W. Van den Hoek; Dirk H. A. Kolff; et al. (1992). Ritual, State, and History in South Asia: Essays in Honour of J.C. Heesterman. BRILL Academic. pp. 68–73 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-09467-9.

- J. C. Heesterman; Albert W. Van den Hoek; Dirk H. A. Kolff; et al. (1992). Ritual, State, and History in South Asia: Essays in Honour of J.C. Heesterman. BRILL Academic. pp. 136–137. ISBN 90-04-09467-9.

- Ramchandra Narayan Dandekar (1981), "Vasistha as Religious Conciliator", in Exercises in Indology, Delhi: Ajanta, pages 122-132, OCLC 9098360

- Findly, Ellison Banks (1984). "Vasistha: Religious Personality and Vedic Culture". Numen. BRILL Academic. 31 (1): 74–77, 98–105. doi:10.2307/3269890. JSTOR 3269890.

- Olivelle 1999, p. 325.

- Olivelle 1999, p. xxvi.

- Vaśiṣṭha Saṃhitā: Yoga kāṇḍa. Kaivalyadhama S.M.Y.M. samiti. 2005. ISBN 978-81-89485-37-5.

- Robert Lingat 1973, p. 18.

- Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 185.

- Chapple 1984, pp. xi-xii

- Surendranath Dasgupta, A History of Indian Philosophy, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521047791, pages 252-253

- Venkatesananda, S (Translator) (1984). The Concise Yoga Vāsiṣṭha. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 51, 77, 87, 121, 147, 180, 188, 306, 315, 354, 410. ISBN 0-87395-955-8.

- Chapple 1984, pp. ix-x with footnote 3

- KN Aiyer (1975), Laghu Yoga Vasishta, Theosophical Publishing House, Original Author: Abhinanda, ISBN 978-0835674973, page 5

- Leslie 2003, pp. 104

- G Watts Cunningham (1948), How Far to the Land of Yoga? An Experiment in Understanding, The Philosophical Review, Vol. 57, No. 6, pages 573-589

- F Chenet (1987), Bhāvanā et Créativité de la Conscience, Numen, Vol. 34, Fasc. 1, pages 45-96 (in French)

- Chapple 1984, pp. x-xi with footnote 4

- Agarwal, D.P. (1990). "Legends as models of Science". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. pp. 41–42. JSTOR 42930266. Missing or empty

|url=(help)(subscription required) - Kanuga, G. B. (1993). Immortal Love of Rama. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 978-1-897829-50-9.

- Harry Hicks and Robert Anderson (1990), Analysis of an Indo-European Vedic Aryan Head – 4500-2500 B.C., in Journal of Indo European studies, Vol. 18, pp 425–446. Fall 1990.

Bibliography

- Chapple, Christopher (1984). "Introduction". The Concise Yoga Vāsiṣṭha. Translated by Venkatesananda, Swami. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-955-8. OCLC 11044869.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robert Lingat (1973). The Classical Law of India. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01898-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Olivelle, Patrick (1999), Dharmasutras: The Law Codes of Ancient India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283882-7

- Patrick Olivelle (2006). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Atreya, B L (1981) [1935)]. The Philosophy of the Yoga Vashista. A Comparative Critical and Synthetic Survey of the Philosophical Ideas of Vashista as presented in the Yoga-Vashista Maha-Ramayan. Based on a thesis approved for the degree of Doctor of Letters in the Banaras Hindu University. Moradabad: Darshana Printers. p. 467.

- Leslie, Julia (2003). Authority and meaning in Indian religions: Hinduism and the case of Vālmīki. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-3431-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Atreya, B L (1993). The Vision and the Way of Vashista. Madras: Indian Heritage Trust. p. 583. OCLC 30508760. Selected verses, sorted by subject, in both Sanskrit and English text.

- Vālmīki (2002) [1982]. The Essence of Yogavaasishtha. Compiled by Sri Jnanananda Bharati, transl. by Samvid. Chennai: Samata Books. p. 344. Sanskrit and English text.

- Vālmīki (1976). Yoga Vashista Sara: The Essence of Yoga Vashista. trans. Swami Surēśānanda. Tiruvannamalai: Sri Ramanasramam. p. 29. OCLC 10560384. Very short condensation.

.jpg)