Calcium in biology

Calcium ions (Ca2+) contribute to the physiology and biochemistry of organisms cell. They play an important role in signal transduction pathways,[1][2] where they act as a second messenger, in neurotransmitter release from neurons, in contraction of all muscle cell types, and in fertilization. Many enzymes require calcium ions as a cofactor, including several of the coagulation factors. Extracellular calcium is also important for maintaining the potential difference across excitable cell membranes, as well as proper bone formation.

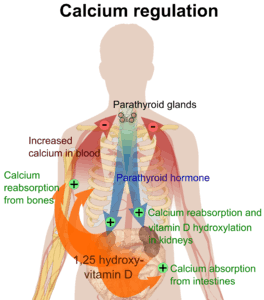

Plasma calcium levels in mammals are tightly regulated,[1][2] with bone acting as the major mineral storage site. Calcium ions, Ca2+, are released from bone into the bloodstream under controlled conditions. Calcium is transported through the bloodstream as dissolved ions or bound to proteins such as serum albumin. Parathyroid hormone secreted by the parathyroid gland regulates the resorption of Ca2+ from bone, reabsorption in the kidney back into circulation, and increases in the activation of vitamin D3 to calcitriol. Calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D3, promotes absorption of calcium from the intestines and bones. Calcitonin secreted from the parafollicular cells of the thyroid gland also affects calcium levels by opposing parathyroid hormone; however, its physiological significance in humans is dubious.

Intracellular calcium is stored in organelles which repetitively release and then reaccumulate Ca2+ ions in response to specific cellular events: storage sites include mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum.[3]

Characteristic concentrations of calcium in model organisms are: in E. coli 3mM (bound), 100nM (free), in budding yeast 2mM (bound), in mammalian cell 10-100nM (free) and in blood plasma 2mM.[4]

Humans

| Age | Calcium (mg/day) |

|---|---|

| 1–3 years | 700 |

| 4–8 years | 1000 |

| 9–18 years | 1300 |

| 19–50 years | 1000 |

| >51 years | 1000 |

| Pregnancy | 1000 |

| Lactation | 1000 |

Dietary recommendations

The U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) established Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for calcium in 1997 and updated those values in 2011.[5] See table. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) uses the term Population Reference Intake (PRIs) instead of RDAs and sets slightly different numbers: ages 4–10 800 mg, ages 11–17 1150 mg, ages 18–24 1000 mg, and >25 years 950 mg.[7]

Because of concerns of long-term adverse side effects such as calcification of arteries and kidney stones, the IOM and EFSA both set Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (ULs) for the combination of dietary and supplemental calcium. From the IOM, people ages 9–18 years are not supposed to exceed 3,000 mg/day; for ages 19–50 not to exceed 2,500 mg/day; for ages 51 and older, not to exceed 2,000 mg/day.[8] The EFSA set UL at 2,500 mg/day for adults but decided the information for children and adolescents was not sufficient to determine ULs.[9]

For U.S. food and dietary supplement labeling purposes the amount in a serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value (%DV). For calcium labeling purposes 100% of the Daily Value was 1000 mg, but as of May 27, 2016 it was revised to 1300 mg to bring it into agreement with the RDA.[10][11] Compliance with the updated labeling regulations was required by 1 January 2020, for manufacturers with $10 million or more in annual food sales, and by 1 January 2021, for manufacturers with less than $10 million in annual food sales.[12][13][14] During the first six months following the 1 January 2020 compliance date, the FDA plans to work cooperatively with manufacturers to meet the new Nutrition Facts label requirements and will not focus on enforcement actions regarding these requirements during that time.[12] A table of the old and new adult Daily Values is provided at Reference Daily Intake.

Health claims

Although as a general rule, dietary supplement labeling and marketing are not allowed to make disease prevention or treatment claims, the FDA has for some foods and dietary supplements reviewed the science, concluded that there is significant scientific agreement, and published specifically worded allowed health claims. An initial ruling allowing a health claim for calcium dietary supplements and osteoporosis was later amended to include calcium and vitamin D supplements, effective January 1, 2010. Examples of allowed wording are shown below. In order to qualify for the calcium health claim, a dietary supplement much contain at least 20% of the Reference Dietary Intake, which for calcium means at least 260 mg/serving.[15]

- "Adequate calcium throughout life, as part of a well-balanced diet, may reduce the risk of osteoporosis."

- "Adequate calcium as part of a healthful diet, along with physical activity, may reduce the risk of osteoporosis in later life."

- "Adequate calcium and vitamin D throughout life, as part of a well-balanced diet, may reduce the risk of osteoporosis."

- "Adequate calcium and vitamin D as part of a healthful diet, along with physical activity, may reduce the risk of osteoporosis in later life."

In 2005 the FDA approved a Qualified Health Claim for calcium and hypertension, with suggested wording "Some scientific evidence suggests that calcium supplements may reduce the risk of hypertension. However, FDA has determined that the evidence is inconsistent and not conclusive." Evidence for pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia was considered inconclusive.[16] The same year the FDA approved a QHC for calcium and colon cancer, with suggested wording "Some evidence suggests that calcium supplements may reduce the risk of colon/rectal cancer, however, FDA has determined that this evidence is limited and not conclusive." Evidence for breast cancer and prostate cancer was considered inconclusive.[17] Proposals for QHCs for calcium as protective against kidney stones or against menstrual disorders or pain were rejected.[18][19]

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that "Calcium contributes to the normal development of bones."[20] The EFSA rejected a claim that a cause and effect relationship existed between the dietary intake of calcium and potassium and maintenance of normal acid-base balance.[21] The EFSA also rejected claims for calcium and nails, hair, blood lipids, premenstrual syndrome and body weight maintenance.[22]

Food sources

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) web site has a very complete searchable table of calcium content (in milligrams) in foods, per common measures such as per 100 grams or per a normal serving.[23][24]

| Food, calcium per 100 grams |

|---|

| parmesan (cheese) = 1140 mg |

| milk powder = 909 mg |

| goat hard cheese = 895 mg |

| Cheddar cheese = 720 mg |

| tahini paste = 427 mg |

| molasses = 273 mg |

| almonds = 234 mg |

| collard greens = 232 mg |

| kale = 150 mg |

| goat milk = 134 mg |

| sesame seeds (unhulled) = 125 mg |

| nonfat cow milk = 122 mg |

| plain whole-milk yogurt = 121 mg |

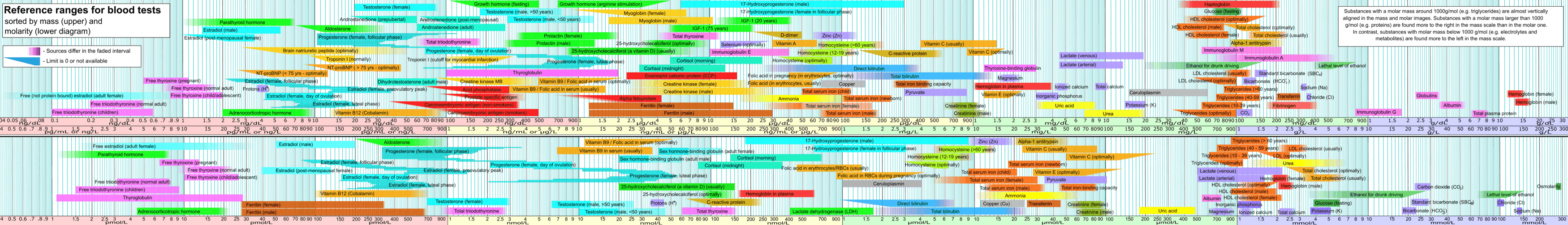

Measurement in blood

The amount of calcium in blood (more specifically, in blood plasma) can be measured as total calcium, which includes both protein-bound and free calcium. In contrast, ionized calcium is a measure of free calcium. An abnormally high level of calcium in plasma is termed hypercalcemia and an abnormally low level is termed hypocalcemia, with "abnormal" generally referring to levels outside the reference range.

| Target | Lower limit | Upper limit | Unit |

| Ionized calcium | 1.03,[25] 1.10[26] | 1.23,[25] 1.30[26] | mmol/L |

| 4.1,[27] 4.4[27] | 4.9,[27] 5.2[27] | mg/dL | |

| Total calcium | 2.1,[28][29] 2.2[26] | 2.5,[26][29] 2.6,[29] 2.8[28] | mmol/L |

| 8.4,[28] 8.5[30] | 10.2,[28] 10.5[30] | mg/dL |

The main methods to measure serum calcium are:[31]

- O-Cresolphalein Complexone Method; A disadvantage of this method is that the volatile nature of the 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol used in this method makes it necessary to calibrate the method every few hours in a clinical laboratory setup.

- Arsenazo III Method; This method is more robust, but the arsenic in the reagent is a health hazard.

The total amount of Ca2+ present in a tissue may be measured using Atomic absorption spectroscopy, in which the tissue is vaporized and combusted. To measure Ca2+ concentration or spatial distribution within the cell cytoplasm in vivo or in vitro, a range of fluorescent reporters may be used. These include cell permeable, calcium-binding fluorescent dyes such as Fura-2 or genetically engineered variant of green fluorescent protein (GFP) named Cameleon.

Corrected calcium

As access to an ionized calcium is not always available a corrected calcium may be used instead. To calculate a corrected calcium in mmol/L one takes the total calcium in mmol/L and adds it to ((40 minus the serum albumin in g/L) multiplied by 0.02).[32] There is, however, controversy around the usefulness of corrected calcium as it may be no better than total calcium.[33] It may be more useful to correct total calcium for both albumin and the anion gap. [34]

Other animals

Vertebrates

In vertebrates, calcium ions, like many other ions, are of such vital importance to many physiological processes that its concentration is maintained within specific limits to ensure adequate homeostasis. This is evidenced by human plasma calcium, which is one of the most closely regulated physiological variables in the human body. Normal plasma levels vary between 1 and 2% over any given time. Approximately half of all ionized calcium circulates in its unbound form, with the other half being complexed with plasma proteins such as albumin, as well as anions including bicarbonate, citrate, phosphate, and sulfate.[35]

Different tissues contain calcium in different concentrations. For instance, Ca2+ (mostly calcium phosphate and some calcium sulfate) is the most important (and specific) element of bone and calcified cartilage. In humans, the total body content of calcium is present mostly in the form of bone mineral (roughly 99%). In this state, it is largely unavailable for exchange/bioavailability. The way to overcome this is through the process of bone resorption, in which calcium is liberated into the bloodstream through the action of bone osteoclasts. The remainder of calcium is present within the extracellular and intracellular fluids.

Within a typical cell, the intracellular concentration of ionized calcium is roughly 100 nM, but is subject to increases of 10– to 100-fold during various cellular functions. The intracellular calcium level is kept relatively low with respect to the extracellular fluid, by an approximate magnitude of 12,000-fold. This gradient is maintained through various plasma membrane calcium pumps that utilize ATP for energy, as well as a sizable storage within intracellular compartments. In electrically excitable cells, such as skeletal and cardiac muscles and neurons, membrane depolarization leads to a Ca2+ transient with cytosolic Ca2+ concentration reaching around 1 uM.[37] Mitochondria are capable of sequestering and storing some of that Ca2+. It has been estimated that mitochondrial matrix free calcium concentration rises to the tens of micromolar levels in situ during neuronal activity.[38]

Effects

The effects of calcium on human cells are specific, meaning that different types of cells respond in different ways. However, in certain circumstances, its action may be more general. Ca2+ ions are one of the most widespread second messengers used in signal transduction. They make their entrance into the cytoplasm either from outside the cell through the cell membrane via calcium channels (such as calcium-binding proteins or voltage-gated calcium channels), or from some internal calcium storages such as the endoplasmic reticulum[3] and mitochondria. Levels of intracellular calcium are regulated by transport proteins that remove it from the cell. For example, the sodium-calcium exchanger uses energy from the electrochemical gradient of sodium by coupling the influx of sodium into cell (and down its concentration gradient) with the transport of calcium out of the cell. In addition, the plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) obtains energy to pump calcium out of the cell by hydrolysing adenosine triphosphate (ATP). In neurons, voltage-dependent, calcium-selective ion channels are important for synaptic transmission through the release of neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft by vesicle fusion of synaptic vesicles.

Calcium's function in muscle contraction was found as early as 1882 by Ringer. Subsequent investigations were to reveal its role as a messenger about a century later. Because its action is interconnected with cAMP, they are called synarchic messengers. Calcium can bind to several different calcium-modulated proteins such as troponin-C (the first one to be identified) and calmodulin, proteins that are necessary for promoting contraction in muscle.

In the endothelial cells which line the inside of blood vessels, Ca2+ ions can regulate several signaling pathways which cause the smooth muscle surrounding blood vessels to relax. Some of these Ca2+-activated pathways include the stimulation of eNOS to produce nitric oxide, as well as the stimulation of Kca channels to efflux K+ and cause hyperpolarization of the cell membrane. Both nitric oxide and hyperpolarization cause the smooth muscle to relax in order to regulate the amount of tone in blood vessels.[39] However, dysfunction within these Ca2+-activated pathways can lead to an increase in tone caused by unregulated smooth muscle contraction. This type of dysfunction can be seen in cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, and diabetes.[40]

Calcium coordination plays an important role in defining the structure and function of proteins. An example a protein with calcium coordination is von Willebrand factor (vWF) which has an essential role in blood clot formation process. It was discovered using single molecule optical tweezers measurement that calcium-bound vWF acts as a shear force sensor in the blood. Shear force leads to unfolding of the A2 domain of vWF whose refolding rate is dramatically enhanced in the presence of calcium.[41]

Adaptation

Ca2+ ion flow regulates several secondary messenger systems in neural adaptation for visual, auditory, and the olfactory system. It may often be bound to calmodulin such as in the olfactory system to either enhance or repress cation channels.[42] Other times the calcium level change can actually release guanylyl cyclase from inhibition, like in the photoreception system.[43] Ca2+ ion can also determine the speed of adaptation in a neural system depending on the receptors and proteins that have varied affinity for detecting levels of calcium to open or close channels at high concentration and low concentration of calcium in the cell at that time.[44]

| Cell type | Effect |

|---|---|

| Endothelial cells | ↑Vasodilation |

| Secretory cells (mostly) | ↑Secretion (vesicle fusion) |

| Juxtaglomerular cell | ↓Secretion[45] |

| Parathyroid chief cells | ↓Secretion[45] |

| Neurons | Transmission (vesicle fusion), neural adaptation |

| T cells | Activation in response to antigen presentation to the T cell receptor[46] |

| Myocytes |

|

| Various | Activation of protein kinase C Further reading: Function of protein kinase C |

Negative effects and pathology

Substantial decreases in extracellular Ca2+ ion concentrations may result in a condition known as hypocalcemic tetany, which is marked by spontaneous motor neuron discharge. In addition, severe hypocalcaemia will begin to affect aspects of blood coagulation and signal transduction.

Ca2+ ions can damage cells if they enter in excessive numbers (for example, in the case of excitotoxicity, or over-excitation of neural circuits, which can occur in neurodegenerative diseases, or after insults such as brain trauma or stroke). Excessive entry of calcium into a cell may damage it or even cause it to undergo apoptosis, or death by necrosis. Calcium also acts as one of the primary regulators of osmotic stress (osmotic shock). Chronically elevated plasma calcium (hypercalcemia) is associated with cardiac arrhythmias and decreased neuromuscular excitability. One cause of hypercalcemia is a condition known as hyperparathyroidism.

Invertebrates

Some invertebrates use calcium compounds for building their exoskeleton (shells and carapaces) or endoskeleton (echinoderm plates and poriferan calcareous spicules).

Plants

Stomata closing

When abscisic acid signals the guard cells, free Ca2+ ions enter the cytosol from both outside the cell and internal stores, reversing the concentration gradient so the K+ ions begin exiting the cell. The loss of solutes makes the cell flaccid and closes the stomatal pores.

Cellular division

Calcium is a necessary ion in the formation of the mitotic spindle. Without the mitotic spindle, cellular division cannot occur. Although young leaves have a higher need for calcium, older leaves contain higher amounts of calcium because calcium is relatively immobile through the plant. It is not transported through the phloem because it can bind with other nutrient ions and precipitate out of liquid solutions.

Structural roles

Ca2+ ions are an essential component of plant cell walls and cell membranes, and are used as cations to balance organic anions in the plant vacuole.[47] The Ca2+ concentration of the vacuole may reach millimolar levels. The most striking use of Ca2+ ions as a structural element in algae occurs in the marine coccolithophores, which use Ca2+ to form the calcium carbonate plates, with which they are covered.

Calcium is needed to form the pectin in the middle lamella of newly formed cells.

Calcium is needed to stabilize the permeability of cell membranes. Without calcium, the cell walls are unable to stabilize and hold their contents. This is particularly important in developing fruits. Without calcium, the cell walls are weak and unable to hold the contents of the fruit.

Some plants accumulate Ca in their tissues, thus making them more firm. Calcium is stored as Ca-oxalate crystals in plastids.

Cell signaling

Ca2+ ions are usually kept at nanomolar levels in the cytosol of plant cells, and act in a number of signal transduction pathways as second messengers.

See also

References

- Brini, Marisa; Ottolini, Denis; Calì, Tito; Carafoli, Ernesto (2013). "Chapter 4. Calcium in Health and Disease". In Astrid Sigel, Helmut Sigel and Roland K. O. Sigel (ed.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 13. Springer. pp. 81–137. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_4. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470090.

- Brini, Marisa; Call, Tito; Ottolini, Denis; Carafoli, Ernesto (2013). "Chapter 5 Intracellular Calcium Homeostasis and Signaling". In Banci, Lucia (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 12. Springer. pp. 119–68. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_5. ISBN 978-94-007-5560-4. PMID 23595672. electronic-book ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1 ISSN 1559-0836 electronic-ISSN 1868-0402

- Wilson, C.H.; Ali, E.S.; Scrimgeour, N.; Martin, A.M.; Hua, J.; Tallis, G.A.; Rychkov, G.Y.; Barritt, G.J. (2015). "Steatosis inhibits liver cell store-operated Ca(2)(+) entry and reduces ER Ca(2)(+) through a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism". Biochem J. 466 (2): 379–390. doi:10.1042/bj20140881. PMID 25422863.

- Milo, Ron; Philips, Rob. "Cell Biology by the Numbers: What are the concentrations of different ions in cells?". book.bionumbers.org. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D Calcium; Ross, A. C.; Taylor, C. L.; Yaktine, A. L.; Del Valle, H. B. (2011). Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D, Chapter 5 Dietary Reference Intakes pages 345-402. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/13050. ISBN 978-0-309-16394-1. PMID 21796828.

- Balk EM, Adam GP, Langberg VN, Earley A, Clark P, Ebeling PR, Mithal A, Rizzoli R, Zerbini CA, Pierroz DD, Dawson-Hughes B (December 2017). "Global dietary calcium intake among adults: a systematic review". Osteoporosis International. 28 (12): 3315–3324. doi:10.1007/s00198-017-4230-x. PMC 5684325. PMID 29026938.

- "Overview on Dietary Reference Values for the EU population as derived by the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies" (PDF). 2017.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D Calcium; Ross, A. C.; Taylor, C. L.; Yaktine, A. L.; Del Valle, H. B. (2011). Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D, Chapter 6 Tolerable Upper Intake Levels pages 403-456. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/13050. ISBN 978-0-309-16394-1. PMID 21796828.

- Tolerable Upper Intake Levels For Vitamins And Minerals (PDF), European Food Safety Authority, 2006

- "Federal Register May 27, 2016 Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels. FR page 33982" (PDF).

- "Daily Value Reference of the Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD)". Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD). Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "FDA provides information about dual columns on Nutrition Facts label". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 December 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Changes to the Nutrition Facts Label". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 27 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Industry Resources on the Changes to the Nutrition Facts Label". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 December 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Food Labeling: Health Claims; Calcium and Osteoporosis, and Calcium, Vitamin D, and Osteoporosis U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- Qualified Health Claims: Letter of Enforcement Discretion - Calcium and Hypertension; Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension; and Preeclampsia (Docket No. 2004Q-0098) U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2005).

- Qualified Health Claims: Letter Regarding Calcium and Colon/Rectal, Breast, and Prostate Cancers and Recurrent Colon Polyps -(Docket No. 2004Q-0097) U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2005).

- Qualified Health Claims: Letter of Denial - Calcium and Kidney Stones; Urinary Stones; and Kidney Stones and Urinary Stones (Docket No. 2004Q-0102) U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2005).

- Qualified Health Claims: Letters of Denial - Calcium and a Reduced Risk Of Menstrual Disorders (Docket No. 2004Q-0099) U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2005)

- Calcium and contribution to the normal development of bones: evaluation of a health claim European Food Safety Authority (2016).

- Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to calcium and potassium and maintenance of normal acid-base balance European Food Safety Authority (2011).

- Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to calcium and maintenance of normal bone and teeth (ID 2731, 3155, 4311, 4312, 4703), maintenance of normal hair and nails (ID 399, 3155), maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 349, 1893), maintenance of normal blood HDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 349, 1893), reduction in the severity of symptoms related to the premenstrual syndrome (ID 348, 1892), “cell membrane permeability” (ID 363), reduction of tiredness and fatigue (ID 232), contribution to normal psychological functions (ID 233), contribution to the maintenance or achievement of a normal body weight (ID 228, 229) and regulation of normal cell division and differentiation EFSA Journal 2010;8(10):1725.

- "Food Composition Databases Show Nutrients List". USDA Food Composition Databases. United States Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- "SR Legacy Nutrient Search". usda.gov. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- Larsson L, Ohman S (November 1978). "Serum ionized calcium and corrected total calcium in borderline hyperparathyroidism". Clin. Chem. 24 (11): 1962–5. doi:10.1093/clinchem/24.11.1962. PMID 709830. Archived from the original on 2019-12-12. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- Reference range list from Uppsala University Hospital ("Laborationslista"). Artnr 40284 Sj74a. Issued on April 22, 2008

- Derived from molar values using molar mass of 40.08 g•mol−1

- Last page of Deepak A. Rao; Le, Tao; Bhushan, Vikas (2007). First Aid for the USMLE Step 1 2008 (First Aid for the Usmle Step 1). McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-149868-5.

- Derived from mass values using molar mass of 40.08 g•mol−1

- Blood Test Results – Normal Ranges Archived 2012-11-02 at the Wayback Machine Bloodbook.Com

- Clin Chem. 1992 Jun;38(6):904-8. Single stable reagent (Arsenazo III) for optically robust measurement of calcium in serum and plasma. Leary NO, Pembroke A, Duggan PF.

- Minisola, S; Pepe, J; Piemonte, S; Cipriani, C (2 June 2015). "The diagnosis and management of hypercalcaemia". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 350: h2723. doi:10.1136/bmj.h2723. PMID 26037642. S2CID 28462200.

- Thomas, Lynn K.; Othersen, Jennifer Bohnstadt (2016). Nutrition Therapy for Chronic Kidney Disease. CRC Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-4398-4950-7.

- Yap, E; Roche-Recinos, A; Goldwasser, P (30 December 2019). "Predicting Ionized Hypocalcemia in Critical Care: An Improved Method Based on the Anion Gap". JALM. 5 (1): 4–14. doi:10.1373/jalm.2019.029314. PMID 32445343.

- Brini, Marisa; Ottolini, Denis; Calì, Tito; Carafoli, Ernesto (2013). "Chapter 4. Calcium in Health and Disease". In Astrid Sigel, Helmut Sigel and Roland K. O. Sigel (ed.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 13. Springer. pp. 81–138. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_4. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470090.

- Boron, Walter F.; Boulpaep, Emile L (2003). "The Parathyroid Glands and Vitamin D". Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approach. Elsevier/Saunders. p. 1094. ISBN 978-1-4160-2328-9.

- https://www.cell.com/abstract/S0092-8674(07)01531-0

- Ivannikov, M.; et al. (2013). "Mitochondrial Free Ca2+ Levels and Their Effects on Energy Metabolism in Drosophila Motor Nerve Terminals". Biophys. J. 104 (11): 2353–2361. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.064. PMC 3672877. PMID 23746507.

- Christopher J Garland, C Robin Hiley, Kim A Dora. EDHF: spreading the influence of the endothelium. British Journal of Pharmacology. 164:3, 839-852. (2011).

- Hua Cai, David G. Harrison. Endothelial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Diseases: The Role of Oxidant Stress. Circulation Research. 87, 840-844. (2000).

- Jakobi AJ, Mashaghi A, Tans SJ, Huizinga EG. Calcium modulates force sensing by the von Willebrand factor A2 domain. Nature Communications 2011 Jul 12;2:385.

- Dougherty, D. P.; Wright, G. A.; Yew, A. C. (2005). "Computational model of the cAMP-mediated sensory response and calcium-dependent adaptation in vertebrate olfactory receptor neurons". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (30): 10415–20. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504099102. PMC 1180786. PMID 16027364.

- Pugh Jr, E. N.; Lamb, T. D. (1990). "Cyclic GMP and calcium: The internal messengers of excitation and adaptation in vertebrate photoreceptors". Vision Research. 30 (12): 1923–48. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(90)90013-b. PMID 1962979.

- Gillespie, P. G.; Cyr, J. L. (2004). "Myosin-1c, the hair cell's adaptation motor". Annual Review of Physiology. 66: 521–45. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.112842. PMID 14977412.

- Boron, Walter F.; Boulpaep, Emile L (2003). Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approach. Elsevier/Saunders. p. 867. ISBN 978-1-4160-2328-9.

- Levinson, Warren (2008). Review of medical microbiology and immunology. McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-07-149620-9.

- White, Philip J.; Martin R. Broadley (2003). "Calcium in Plants". Annals of Botany. 92 (4): 487–511. doi:10.1093/aob/mcg164. PMC 4243668. PMID 12933363.