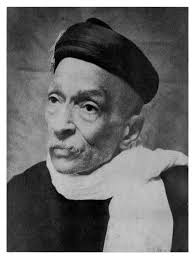

Ramachandra Dattatrya Ranade

Ramachandra Dattatrya Ranade (1886–1957) was a scholar-philosopher-saint of Karnataka and Maharashtra.

Ramchandra Dattatrya Ranade | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1886 A.D. Jamakhandi, Bagalkot District, Karnataka, India |

| Died | 1957 A.D. Nimbal, near Bijapur, Karnataka, India |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Occupation | Teaching, Retired as Head of Department of Philosophy, Allahabad University; Vice-Chancellor, Allahabad University. |

| Known for | His work on Upanishads – A constructive survey of Upanishadic philosophy |

Biography

He was born on 3 July 1886 in Jamakhandi, in Bagalkot District of Karnataka. After completing his schooling he studied at Deccan College, Pune. In the year 1914 he passed M.A. with full honours and for a very brief period joined the teaching staff of Fergusson College, Pune. He taught at Willindon College, Sangli, on a regular basis before being invited to join Allahabad University as Head of Department of Philosophy where he rose to be the Vice-Chancellor. After retirement in 1946 he lived in an ashrama in a small village, Nimbal, on border of Maharashtra and Karnataka, near Vijaypura ( Bijapur) where he died on 6 June 1957.

Philosophy

According to Ranade, the three main approaches in arriving at the solution to the problem of the Ultimate Reality have traditionally been the theological, the cosmological and the psychological approaches.[1] The cosmological approach involves looking outward, to the world; the psychological approach meaning looking inside or to the Self; and the theological approach is looking upward or to God. Descartes takes the first and starts with the argument that the Self is the primary reality, self-consciousness the primary fact of existence, and introspection the start of the real philosophical process.[2] According to him, we can arrive at the conception of God only through the Self because it is God who is the cause of the Self and thus, we should regard God as more perfect than the Self. Spinoza on the other hand, believed that God is the be-all and the end-all of all things, the alpha and the omega of existence. From God philosophy starts, and in God philosophy ends. The manner of approach of the Upanishadic philosophers to the problem of ultimate reality was neither the Cartesian nor Spinozistic. The Upanishadic philosophers regarded the Self as the ultimate existence and subordinated the world and God to the Self. The Self to them, is more real than either the world or God. It is only ultimately that they identify the Self with God, and thus bridge over the gulf that exists between the theological and psychological approaches to reality. They take the cosmological approach to start with, but they find that this cannot give them the solution of the ultimate reality. So, Upanishadic thinkers go back and start over by taking the psychological approach and here again, they cannot find the solution to the ultimate reality. They therefore perform yet another experiment by taking the theological approach. They find that this too is lacking in finding the solution. They give yet another try to the psychological approach, and come up with the solution to the problem of the ultimate reality. Thus, the Upanishadic thinkers follow a cosmo-theo-psychological approach.[2] A study of the mukhya Upanishads shows that the Upanishadic thinkers progressively build on each other's ideas. They go back and forth and refute improbable approaches before arriving at the solution of the ultimate reality.[3]

Works

He was a good orator who was also a good writer. His monumental work that made him famous, A Constructive Survey of Upanishadic Philosophy,[4] was published by Oriental Books Agency, Pune, in 1926 under the patronage of Sir Parashuramarao Bhausaheb, Raja of Jamkhandi.[5] He also wrote Pathways to God in Hindi and Marathi[6] and Ramdasvacanamrut, which is based on the scriptures of Samarth Ramdas. As an eminent scholar of the Upanishads who had specialised in Greek philosophy, Ranade emphasised the centrality of the psychological approach as opposed to the theological approach for the proper understanding of the Ultimate Reality.[7]

Inchegiri Sampradaya

Ranade belonged to the Inchegeri Sampradaya.

| Inchegeri Sampradaya | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rishi Dattatreya, mythological deity-founder.[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||

| Navnath, the nine founders of the Nath Sampradaya,[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4] | |||||||||||||

| Gahininath,[lower-alpha 5] the 5th Navnath[lower-alpha 6] | Revananath, the 7th[lower-alpha 7] or 8th[lower-alpha 8] Navnath, also known as Kada Siddha[lower-alpha 9] | Siddhagiri Math[lower-alpha 10][lower-alpha 11] c.q. Kaneri Math (est. 7th[lower-alpha 12] or 14th century[lower-alpha 13]; Lingayat Parampara[lower-alpha 14] c.q. Kaadasiddheshwar Parampara[lower-alpha 15] | |||||||||||

| Nivruttinath, Dnyaneshwar's brother[lower-alpha 16] | |||||||||||||

| Dnyaneshwar[lower-alpha 17] (1275–1296) also known as Sant Jñāneshwar or Jñanadeva[lower-alpha 18] and as Kadasiddha[lower-alpha 19] or Kad-Siddheshwar Maharaj[lower-alpha 20] | |||||||||||||

|

Different accounts: | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Nimbargi Maharaj (1789-1875) also known as Guru Lingam-Jangam Maharaj [lower-alpha 28][lower-alpha 29][lower-alpha 30] |

23rd Shri Samarth Muppin Kaadsiddheswar Maharaj | |||||||||||

| 2 | Shri Bhausaheb Maharaj Umdikar[lower-alpha 31][lower-alpha 32] (1843 Umdi - 1914 Inchgiri[lower-alpha 33]) | 24th Shri Samarth Muppin Kaadsiddheswar Maharaj | |||||||||||

| 3 | H.H. Shri Amburao Maharaj of Jigjivani (1857 Jigajevani - 1933 Inchgiri)[lower-alpha 34][lower-alpha 35] |

Shivalingavva Akka (1867-1930)[lower-alpha 36] | Girimalleshwar Maharaj[lower-alpha 37][lower-alpha 38] | Sri Siddharameshwar Maharaj (1875-1936)[lower-alpha 39][lower-alpha 40] | 25th Shri Samarth Muppin Kaadsiddheswar Maharaj | ||||||||

| 4 | H.H. Shri Gurudev Ranade of Nimbal (1886-1957)[lower-alpha 41][lower-alpha 42][lower-alpha 43][lower-alpha 44][lower-alpha 45] | Balkrishna Maharaj[lower-alpha 46] | Shri Aujekar Laxman Maharaj[lower-alpha 47] | Madhavananda Prabhuji (d. 25th May, 1980)[lower-alpha 48] |

Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj (1897–1981)[lower-alpha 49] |

|

26th Shri Muppin Kaadsiddheshwar Maharaj (1905-2001) Student of Sri Siddharameshwar Maharaj[lower-alpha 55] | ||||||

| 5 | H.H Shri Gurudev Chandra Bhanu Pathak[lower-alpha 56] | Bhausaheb Maharaj (Nandeshwar)[lower-alpha 57] | Shri Nagnath Alli Maharaj[lower-alpha 58] |

|

27th head: H.H. Adrushya Kadsiddheshwar Swamiji[lower-alpha 76] | H. H. Jagadguru Ramanandacharya Shree Swami Narendracharyaji Maharaj[lower-alpha 77] | |||||||

| |||||||||||||

References

- Ranade 1926, p. 247.

- Ranade 1926, p. 248.

- Ranade 1926, pp. 249–278.

- R.D.Ranade. A Constructive Survey of Upanishadic Philosophy.

- Jashan P. Vaswani (1 August 2008). Sketches of Saints Known and Unknown. New Delhi: Sterling Paperbacks (P) Ltd. p. 197 to 202. ISBN 9788120739987.

- Harold G. Coward (30 October 1987). Modern Indian Responses to Religious Pluralism. Suny Press. p. 181. ISBN 9780887065729.

- Nalini Bhushan Jay L. Garfield (26 August 2011). Indian Philosophy in English: From Renaissance to Independence. Oxford University Press. p. 245. ISBN 9780199911288.

Sources

- Ranade, R. D. (1926), A constructive survey of Upanishadic philosophy, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan