Kalpa (Vedanga)

Kalpa (Sanskrit: कल्प) means "proper, fit" and is one of the six disciplines of the Vedānga, or ancillary science connected with the Vedas – the scriptures of Hinduism.[1] This field of study is focused on the procedures and ceremonies associated with Vedic ritual practice.[2][1]

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

|

Timeline |

The major texts of Kalpa Vedanga are called Kalpa Sutras in Hinduism.[3] The scope of these texts includes Vedic rituals, rites of passage rituals associated with major life events such as birth, wedding and death in family, as well as personal conduct and proper duties in the life of an individual.[4] Most Kalpasutras texts have experienced interpolation, changes and consequent corruption over their history, and Apasthamba Kalpasutra ancillary to the Yajurveda may be the best preserved text in this genre.[5]

Kalpa Sutras are also found in other Indian traditions, such as Jainism.[6]

Etymology

Kalpa is a Sanskrit word that means "proper, fit, competent, sacred precept", and also refers to one of the six Vedanga fields of study.[7] In Vedanga context, the German Indologist Max Muller translates it as "the Ceremonial".[8]

The word is widely used in other contexts, such as "cosmic time" (one day for Brahma, 4.32 billion human years),[9] as well as for precepts or procedures that are "proper, fit" in medicine or another profession.[7]

History

The Kalpa field of study traces it roots to the Brahmana layer of texts in the Vedas,[10] however its texts are more focussed, clear, short and practical for ceremonies.[8][11] Kalpa Sutras are related to the Karma kanda, or ritual parts of the Veda, in contrast to the Upanishads which are the Jnana kanda, or the knowledge part.[12][13]

This field of study emerged to serve the needs of priests as they officiated over domestic ceremonies such as weddings and baby naming rites of passage, so that the rituals were efficient, standardized and appeared consistent across different events.[10] They also helped the audience and the individuals integrate within customs and cultural practices, state Winternitz and Sarma, from "the moment when he is received in his mother's womb to the hour of his death", and beyond during his cremation.[10]

Texts

| Veda | Sutras |

| Rigveda | Asvalayana-sutra (§), Sankhayana-sutra (§), Saunaka-sutra (¶) |

| Samaveda | Latyayana-sutra (§), Drahyayana-sutra (§), Nidana-sutra (§), Pushpa-sutra (§), Anustotra-sutra (§)[15] |

| Yajurveda | Manava-sutra (§), Bharadvaja-sutra (¶), Vadhuna-sutra (¶), Vaikhanasa-sutra (¶), Laugakshi-sutra (¶), Maitra-sutra (¶), Katha-sutra (¶), Varaha-sutra (¶) |

| Atharvaveda | Kusika-sutra (§) |

| ¶: only quotes survive; §: text survives | |

The rituals related ancient texts are of two kinds: (1) the Śrautasūtras, which are based on the śruti, and (2) the Smārtasūtras, or rules based on the smriti or tradition. The first versions of the Kalpa Sutras text were probably composed by the 6th-century BCE, and they were attributed to famous Vedic sages out of respect for them in the Hindu traditions or to gain authority.[1] These texts are written aphoristic sutras style, and therefore are taxonomies or terse guidebooks rather than detailed manuals or handbooks for any ceremony.[11]

Scholars such as Monier-Williams classified only Shrautasutras as part of Kalpa Vedanga, stating that the Smartasutras did not relate to Srauta or Vedic ceremonies, but instead focused on domestic events such as rites of passage when a baby is born and to Samayachara or "conventional everyday practices" that are part of every human being's life.[16] However, other scholars include both.[10][13]

Srauta Sutras

The Śrautasūtras (Shrauta-sutra) form a part of the corpus of Sanskrit sūtra literature. Their topics include instructions relating to the use of the śruti corpus in ritual ('kalpa') and the correct performance of these rituals. Some early Śrautasūtras were composed in the late Brahmana period (such as the Baudhyanana and Vadhula Sūtras), but the bulk of the Śrautasūtras are roughly contemporary to the Gṛhya corpus of domestic sūtras, their language being late Vedic Sanskrit, dating to the middle of the first millennium BCE (generally predating Pāṇini).

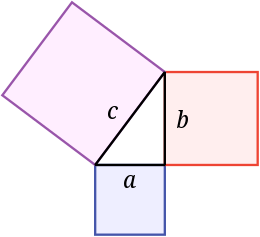

Shulba Sutras

The Śulbasûtra (or Shulva-sutras) deal with the mathematical methodology to construct altar geometries for the Vedic rituals.[18] The Sanskrit word "Shulba" means cord, and these texts are "rules of the cord".[19] They provide, states Kim Plofker, what in modern mathematical terminology would be called "area preserving transformations of plane figures", tersely describing geometric formulae and constants.[19] Five Shulba Sutras texts have survived through history, of which the oldest surviving is likely the Baudhayana Shulba Sutra (800-500 BCE), while the one by Katyayana may be chronologically the youngest (~300 BCE).[20]

Smarta Sutras

The Gṛhyasūtras "domestic sūtras" are a category of Sanskrit texts prescribing Vedic rituals, mainly relating to rites of passage such as rituals of wedding, birth celebration, namegiving and coming of age (puberty).[21][22] Their language is late Vedic Sanskrit, and they date to around roughly 500 BCE, contemporary with the Śrautasūtras. They are named after Vedic shakhas.

Vedic sacrifice rituals at a wedding

West of the (sacred) fire, a stone (for grinding corn and condiments) is placed and northeast a water jar. The bridegroom offers an oblation, standing, looking towards the west, and taking hold of the bride's hands while she sits and looks towards the east. If he wishes only for sons, he clasps her thumbs and says, "I clasp thy hands for the sake of good fortune"; the fingers alone, if he wishes only for daughters; the hairy side of the hand along with the thumbs if wishes for both (sons and daughters). Then, whilst he leads her towards the right three times around the fire, and round the water jar, he says in a low tone,

"I am he, thou are she; thou art she, I am he,

I am the heaven, thou art the earth; I am the Saman, thou art the Rig.

Come let us marry, let us possess offspring,

united in affection, well disposed to each other,

let us live for a hundred years".

— Āśvalāyana Kalpa sutra, Book 1.7, Translated by Monier Monier-Williams[23][24]

Dharmasūtras

The Dharmasūtras are texts dealing with custom, rituals, duties and law. They include the four surviving written works of the ancient Indian tradition on the subject of dharma, or the rules of behavior recognized by a community. Unlike the later dharmaśāstras, the dharmasūtras are composed in prose. The oldest dharmasūtra is generally believed to have been that of Apastamba, followed by the dharmasūtras of Gautama, Baudhayana, and an early version of Vashistha. It is difficult to determine exact dates for these texts, but the dates between 500–300 BCE have been suggested for the oldest dharmasūtras.

| Veda | Srautasutra[25] | Sulbasutra[25] | Grihyasutra[25] | Dharmasutra[25] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ṛgveda | Āśvalāyana Śrautasūtra[26] Sāṅkhāyana Śrautasūtra | Âśvalāyana-Gṛhyasūtra [26] Kausîtaki-Gṛhyasūtra (Bāṣkala śakha) Śāṅkhāyana-Gr̥hyasūtra | Vasishtha Dharmasūtra | |

| Sāmaveda | Lātyāyana Śrautasūtra Drāhyāyana Śrautasūtra Jaiminiya Śrautasūtra | Gobhila-Gṛhyasūtra Khādira-Gṛhyasūtra (Drāhyāyana-Gṛhyasūtra) Jaiminiya-Gṛhyasūtra Kauthuma-Gṛhyasūtra | Gautama Dharmasūtra | |

| Kṛsna Yajurveda | Baudhāyana Śrautasūtra Vādhūla Śrautasūtra Mānava Śrautasūtra Bharadvāja Śrautasūtra Āpastamba Śrautastūra Hiraṅyakeśi Śrautasūtra Vārāha Śrautasūtra Vaikhānasa Śrautasūtra | Baudhāyana Śulbasûtra Mānava Śulbasûtra Āpastamba Śulbasûtra | Baudhāyana-Gṛhyasūtra Hiraṇyakeśi-Gṛhyasūtra (Satyāsādha-Gṛhyasūtra) Mānava-Gṛhyasūtra Bhāradvāja-Gṛhyasūtra Āpastamba-Gṛhyasūtra Āgniveśya-Gṛhyasūtra Vaikhānasa-Gṛhyasūtra Kāthaka-Gṛhyasūtra (Laugāksi-Gṛhyasūtra) Vārāha-Gṛhyasūtra Vādhûla-Gṛhyasūtra Kapisthala-Katha Gṛhyasūtra (unpublished) | Baudhāyana Dharmasūtra Āpastamba Dharmasūtra |

| Śukla Yajurveda | Kātyāyana Śrautasūtra | Kātyāyana Śulbasūtra | Pāraskara-Gṛhyasūtra Katyayana-Gṛhyasūtra | Vishnu Dharmasūtra |

| Atharvaveda | Vaitāna Śrautasũtra | Kauśika Gṛhyasūtra |

See also

- Kalpa Sūtra, scriptures of Jainism

- Mīmāṃsā

- Orthopraxy

References

- James Lochtefeld (2002), "Kalpa" in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A-M, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, page 339

- Kim Plofker 2009, p. 313.

- Maurice Winternitz 1963, p. 252.

- Wendy Doniger (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. pp. 629. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- Patrick Olivelle (1999). The Dharmasutras: The Law Codes of Ancient India. Oxford University Press. pp. xxv-xxviii with footnotes. ISBN 978-0-19-160604-5.

- Moriz Winternitz (1988). A History of Indian Literature: Buddhist literature and Jaina literature. Motilal Banarsidass (Reprint). pp. 412–413, 444–446. ISBN 978-81-208-0265-0.

- Monier Monier-Williams (1923). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. pp. 212–213.

- Friedrich Max Müller (1860). A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature. Williams and Norgate. pp. 169–170.

- James Lochtefeld (2002), "Kalpa" in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A-M, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, page 338

- Moriz Winternitz; V. Srinivasa Sarma (1996). A History of Indian Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 252–262. ISBN 978-81-208-0264-3.

- Brian K. Smith (1998). Reflections on Resemblance, Ritual, and Religion. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 120–137 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-208-1532-2.

- Kireet Joshi (1991). The Veda and Indian Culture: An Introductory Essay. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-81-208-0889-8.

- Barbara A. Holdrege (2012). Veda and Torah: Transcending the Textuality of Scripture. State University of New York Press. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-1-4384-0695-4.

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, pages 198-199

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, page 210

- Monier Monier-Williams (1876). Indian Wisdom. W. H. Allen & Company. pp. 195–198.

- Kim Plofker 2009, p. 18 with note 13.

- Pradip Kumar Sengupta (2010). History of Science and Philosophy of Science. Pearson. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-81-317-1930-5.

- Kim Plofker 2009, p. 17.

- Kim Plofker 2009, pp. 17-18.

- Hermann Oldenberg, trans., Max Müller, ed. Sacred Books of the East Vol. XXIX, "The Grihya-sûtras, rules of Vedic domestic ceremonies", part 1, Oxford, The Clarendon press 1886

- Hermann Oldenberg, trans., Max Müller, trans. Sacred Books of the East Vol. XXX, "The Grihya-sûtras, rules of Vedic domestic ceremonies", part 2, Oxford, The Clarendon press 1892

- Monier Monier-Williams (1876). Indian Wisdom. W. H. Allen & Company. p. 199.

- Subodh Kapoor (2002). Encyclopaedia of vedic philosophy. Cosmo. pp. 2114–2115. ISBN 978-81-7755-290-4.

- Kochar, Rajesh Vedic People:Their History and Geography, Orient Longman, New Delhi, 2000, ISBN 81-250-1080-7, p.18

- Catalogue of Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit Books in the British Museum (1876) p. 9. Gargya's commentaries (vrttis) are based on the longer bhashyas by Devasvamin (11th century). B.K. Sastry, review Archived 2016-03-14 at the Wayback Machine of K. P. Aithal (ed.), Asvalayana Grihya Sutra Bhashyam of Devasvamin, 1983.

Bibliography

- Kim Plofker (2009). Mathematics in India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12067-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maurice Winternitz (1963). History of Indian Literature, Volume 1. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0056-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)