Vyasatirtha

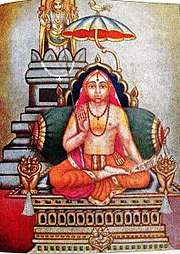

Vyāsatīrtha (c.. 1460 – c. 1539[1]), also called Vyasaraja or Chandrikacharya, was a Hindu philosopher, scholar and poet belonging to the Dvaita order of Vedanta. As the patron saint of the Vijayanagara Empire, Vyasatirtha was at the forefront of a golden age in Dvaita which saw new developments in dialectical thought, growth of the Haridasa literature under bards like Purandara Dasa and Kanaka Dasa and an amplified spread of Dvaita across the subcontinent. Three of his polemically themed doxographical works Nyayamruta, Tatparya Chandrika and Tarka Tandava (collectively called Vyasa Traya) documented and critiqued an encyclopaedic range of sub-philosophies in Advaita,[note 1] Visistadvaita, Mahayana Buddhism, Mimamsa and Nyaya, revealing internal contradictions and fallacies. His Nyayamruta caused a significant stir in the Advaita community across the country requiring a rebuttal by Madhusudhana Saraswati through his text, Advaitasiddhi.

Sri Vyasatirtha | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | Yatiraja Around 1460 |

| Died | 1539 |

| Resting place | Nava Brindavana |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| School | Dvaita |

| Religious career | |

| Guru | Sripadaraja, Bramhanya Tirtha |

| Predecessor | Bramhanya Tirtha |

Disciples

| |

| Honors | Chandrikacharya, Vyasaraja |

| Part of a series on |

| Dvaita |

|---|

|

|

Literature

|

|

|

Holy places |

| Hinduism portal |

Born into a Brahmin family as Yatiraja, Bramhanya Tirtha, the pontiff of the matha at Abbur, assumed guardianship over him and oversaw his education. He studied the six orthodox schools of Hinduism at Kanchi and subsequently, the philosophy of Dvaita under Sripadaraja at Mulbagal, eventually succeeding him as the pontiff. He served as a spiritual adviser to Saluva Narasimha Deva Raya at Chandragiri though his most notable association was with the Tuluva king Krishna Deva Raya. With the royal patronage of the latter, Vyasatirtha undertook a massive expansion of Dvaita into the scholarly circles, through his polemical tracts as well as into the lives of the laymen through devotional songs and poems. In this regard, he penned several kirtanas under the nom de plume of Krishna including the classical Carnatic song Krishna Ni Begane Baaro. Politically, Vyasatirtha was responsible for the development of irrigation systems in villages such as Bettakonda and establishment of several Vayu temples in the newly conquered regions between Bengaluru and Mysore in-order to quell any rebellion and facilitate their integration into the Empire.

For his contribution to the Dvaita school of thought, he, along with Madhva and Jayatirtha, are considered to be the three great saints of Dvaita (munitraya). Scholar Surendranath Dasgupta notes, "The logical skill and depth of acute dialectical thinking shown by Vyasa-tirtha stands almost unrivalled in the whole field of Indian thought".[3]

Historical Sources

Information about Vyasatirtha is derived from his biography by the poet Somanatha Kavi called Vyasayogicharita and inscriptional evidence. Songs of Purandara Dasa and traditional stories yield important insights too. Though Vyasayogicharita is a hagiography, unlike other works in the genre, it is free of embellishments such as performance of miracles and some of its claims can be corroborated with inscriptional evidence.[4] Somanatha mentions at the end of the text that the biography was approved by Vyasatirtha himself, implying the contemporary nature of the work. While some scholars attest the veracity of the text to the claim that Somanatha was a Smartha hence free of sectarian bias,[5][6] others question the claim citing a lack of evidence.[7][8]

Context

The philosophy of Dvaita or Tattvavada was an obscure movement within Vedanta in medieval India. Philosophically, its tenets stood in direct opposition to Advaita in that its progenitor, Madhva, postulated that the self (Atman) and god (Brahman) are distinct and that the world is real. As Advaita was the prevailing sub-sect of Vedanta at the time, the works of Madhva and his followers came under significant attack and ridicule.[9] Madhva deployed his disciples to promulgate the philosophy across the country, which led to the establishment of a small and diffuse network of mathas, or centres of worship, across the subcontinent.[10] The early years of Dvaita were spent spreading its basic tenets including participating in debates with the Advaita scholars.[11]

Philosophical improvements were pioneered by Padmanabha Tirtha and subsequently perfected by Jayatirtha. Dasgupta contends that the latter's contributions brought Dvaita up to the standards of intellectual sophistication set by Advaita and Visistadvaita.[3] By imbuing the nascent philosophy with structure and expanding upon Madhva's terse texts, he reinforced the intellectual position of Madhva and set the standard for Dvaita literature through his seminal work, Nyaya Sudha ('Nectar of Logic').[12] Subsequent authors such as Vishnudasacharya further expanded upon these texts and authored commentaries branching into diverse fields such as Mimamsa and Navya Nyaya, a tradition which would continue for centuries. Despite the intellectual growth, due to the turbulent political atmosphere of India at the time, penetration of Dvaita into the cultural collective of the subcontinent was limited.[13][14] It was not until Sripadaraja, the pontiff of the matha at Abbur, who aligned himself with the Vijaynagara king Saluva Narasimha Deva Raya and served as his guru, that Dvaita would receive royal encouragement and a certain degree of power.[15] But the Smartha Brahmins, adhering to the principles of Advaita, and Sri Vaishnavites, following the Visistadvaita philosophy of Ramanuja, controlled the Shiva and Vishnu temples respectively, thus limiting the influence of Dvaita.[14]

Early life

Vyasatirtha was born Yatiraja into a Deshastha Madhva Brahmin family [16] to Ballanna and Akkamma in a hamlet called Bannur. According to Vyasayogicharita, the childless couple approached saint Bramhanya Tirtha, who granted them a boon of three children with the condition that the second child, who would turn out to be Yatiraja, be handed over to him. After Yatiraja's upanayana, Bramhanya Tirtha assumed guardianship over the child.[17] Bramhanya was genuinely surprised by the precocious intellect of the child and intended to ordain him as a monk. Yatiraja, anticipating the ordination, decided to run away from the hermitage. While resting under a tree, he had a vision of Vishnu, who urged Yatiraja to return, which he did. He was subsequently ordained as Vyasatirtha. Indologist B.N.K Sharma contends that Vyasatirtha would have been 16 years of age at this time.[18]

After the death of Bramhanya Tirtha during the famine of 1475–1476, Vyasatirtha succeeded him as the pontiff of the matha at Abbur and proceeded to Kanchi, which was the centre for Sastric learning in South India at the time, to educate himself on the six orthodox schools of thought, which are: Vedanta, Samkhya, Nyaya, Mimamsa, Vaisheshika and Yoga. Sharma conjectures that the education Vyasatirtha received in Kanchi helped him become erudite in the intricacies and subtleties of Advaita, Visistadvaita, Navya Nyaya and other schools of thought.[18] After completing his education at Kanchi, Vyasatirtha headed to Mulbagal to study the philosophy of Dvaita under Sripadaraja, whom he would consider his guru, for a period of five to six years. He was subsequently sent to the Vijayanagara court of Saluva Narasimha Deva Raya at the behest of Sripadaraja.[19]

At Chandragiri

Vyasatirtha was received by Saluva Narasimha at Chandragiri.[19] Somanatha speaks of several debates and discussions in which Vyasatirtha emerged triumphant over the leading scholars of the day. He also talks about Vyasatirtha giving spiritual guidance to the king. Around the same time, Vyasatirtha was entrusted with the worship of the Venkateshwara idol at Tirupati and undertook his first South Indian tour (a tour entailing travelling to different regions in order to spread the doctrines of Dvaita). After the death of Saluva Narasimha, Vyasatirtha remained at Chandragiri in the court of Narasimha Raya II until Tuluva Narasa Nayaka declared himself to be the de facto ruler of Vijayanagara.[20] At the behest of Narasa, Vyasatirtha moved to Hampi and would remain there for the rest of his life. After the death of Narasa, his son Viranarasimha Raya was subsequently crowned.[21] Some scholars argue against the claim that Vyasatirtha acted as a spiritual adviser to Saluva Narasimha, Narasimha II and Vira Narasimha due to the lack of inscriptional evidence.[22][8]

At Hampi

At Hampi, the new capital of the empire, Vyasatirtha was appointed as the "Guardian Saint of the State" after a period of prolonged disputations and debates with scholars led by Basava Bhatta, an emissary from the Kingdom of Kalinga.[23] His association with the royalty continued after Viranarasimha Raya overthrew Narasimha Raya II to become the emperor. Fernão Nunes observes that "The King of Bisnega, everyday, hears the teachings of a learned Brahmin who never married nor ever touched a woman" which Sharma conjectures is Vyasatirtha.[24] Sharma also contends that it was around this time that Vyasatirtha had begun his work on Tatparya Chandrika, Nyayamruta and Tarka Tandva.[24] After the accession of Krishnadeva Raya, Vyasatirtha, who the king regarded as his kuladevata, greatly expanded his influence by serving as an emissary and diplomat to the neighbouring kingdoms while simultaneously disseminating the philosophy of Dvaita into the subcontinent. His close relationship to Krishnadeva Raya is corroborated by inscriptions on the Vitthala Temple at Hampi and accounts by the Portuguese traveler Domingo Paes.[25][note 2]

Vyasatirtha was also sent on diplomatic missions to the Bijapur Sultante and accepted grants of villages in newly conquered territories for the establishment of Mathas. Stoker conjectures that this was advantageous to both the king and Vyasatirtha as the establishments of mathas in these newly conquered regions led to political stability and also furthered the reach of Dvaita.[26] Somanatha writes of an incident where Krishnadeva Raya was sent a work of criticism against Dvaita by an Advaita scholar in Kalinga as a challenge. After Vyasatirtha retaliated accordingly, Krishnadeva Raya awarded Vyasatirtha with a ratnabhisheka (a shower of jewels) which Vyasatirtha subsequently distributed among the poor.[27][28] The inscriptions speak of grants of villages to Vyasatirtha from Krishnadeva Raya around this period, including Bettakonda, where he developed large irrigation systems including a lake called Vyasasamudra.[19] This period of Vyasatirtha also saw the establishment of Dasakuta (translated as community of devotees), a forum where people gathered and sung hymns and devotional songs. The forum attracted a number of wandering bards (called Haridasas or devotees of Vishnu) such as Purandara Dasa and Kanaka Dasa.[29]

Later Years

There was a period of "temporary estrangement" from the royalty due to internal political friction, during which Vyasatirtha retreated to Bettakonda.[28] After the death of Krishnadeva Raya, Vyasatirtha continued to advise Achyuta Deva Raya. Inscriptions speak of his donation of a Narasimha idol to the Vittala Temple at Hampi indicating he was still an active figure.[30] His disciples Vijayendra Tirtha and Vadiraja Tirtha furthered his legacy by penning polemical works and spreading the philosophy of Dvaita into the Chola and the Malnad region, eventually assuming pontifical seats at Kumbakonam and Sodhe, respectively. He died in 1539 and his mortal remains are enshrined in Nava Brindavana, near Hampi. His remembrance day every year (called Aradhana) is celebrated in the month of Phalguna. He was succeeded by his disciple, Srinivasa Tirtha.

Works

Vyasatirtha authored eight works consisting of polemical tracts, commentaries on the works of Madhva and a few hymns. Visnudasacharya's Vadaratnavali, a polemical treatise against the tenets of Advaita, is considered to have significant influenced him.[32] By tracing a detailed, sophisticated and historically sensitive evolution of systems of thought such as Advaita, Vyakarana, Nyaya and Mimamsa and revealing internal inconsistencies, McCrea contends that Vyasatirtha created a new form of doxography.[33] Ramanuja's Visistadvaita as well as Nagarjuna's Madhyamaka is dealt with in Nyayamruta.[34] This style of polemics influenced Appayya Dikshita, who authored his own doxographical work titled Śātrasiddhāntaleśasaṃgraha.[33]

Nyayamruta

Nyayamruta is a polemical and expositional work in four chapters.[35] Advaita assumes that the world and its multiplicity is the result of the interaction between Maya (sometimes also characterized as avidya or ignorance) and the Brahman.[36] Therefore, according to Advaita, the world is nothing more than an illusory construct.[37] The definition of this falsity of the world (called mithyatva) varies within Advaita with some opining that the world has various degrees of reality[38] for example Appayya Dikshita assumes three degrees, while Madhusudhana Saraswati assumes two.[39] The first chapter of Nyayamruta refutes these definitions of reality.[35]

In the second chapter, Vyasatirtha examines role of pramanas in Dvaita and Advaita.[40] Pramana translates to "proof" or "means of knowing".[41] Dvaita assumes the validity of three pramanas: pratyeksha (direct experience), anumana (inference) and sabda (agama).[42] Here, Vyasatirtha argues that the principles of Dvaita can be supported by the relevant pramanas and demonstrates this by verifying Madhva's doctrine of five fold difference accordingly.[40][note 4] Subsequently, the Advaita concept of Nirguna Brahman is argued against.[35] While the third deals with the critique of the Advaita view on the attainment of true knowledge (jnana), the fourth argues against soteriological issues in Advaita like Moksha, specifically dealing with the concept of Jivanmukti (enlightenment while alive).[35] Vyasatirtha asks whether, for an Advaitin, the body ceases to exist after the veil of illusion has been lifted and the unity with the Brahman has been attained.

Nyayamruta caused a furore in the Advaita community resulting in a series of scholarly debates over centuries. Madhusudhana Saraswati, a scholar from Varanasi, composed a line-by-line refutation of Nyayamruta titled Advaitasiddhi.[43] In response, Ramacharya rebutted with Nyayamruta Tarangini [44] and Anandabhattaraka with Nyayamruta Kantakoddhara.[45] The former is criticised by Brahmananda Saraswati in his commentary on Advaitasiddhi, Guruchandrika.[46] Vanamali Mishra composed a refutation of the Bramhananda Saraswati's work and the controversy eventually died down.[47] Stoker conjectures that the strong responses Vyasatirtha received were due to the waning power of Advaita in the Vijayanagara empire coupled by the fact that as an administrator of the mathas, Vyasatirtha enjoyed royal patronage.[14]

Vyasatirtha's disciple Vijayendra Tirtha has authored a commentary on the Nyayamruta called Laghu Amoda.

Tatparya Chandrika

Tatparya Chandrika or Chandrika is a commentary on Tattva Prakasika by Jayatirtha, which in turn is a commentary on Madhva's Brahma Sutra Bhashya (which is a bhashya or a commentary on Badarayana's Brahma Sutra). It not only documents and analyses the commentaries of Shankara, Madhva and Ramanuja on the Brahma Sutra but also their respective sub-commentaries.[note 5] The goal of Vyasatirtha here is to prove the supremacy of Madhva's Brahma Sutra Bhashya by showing it to be in harmony with the original source, more so than the other commentaries. The doxographical style of Vyasatirtha is evident in his copious quotations from the main commentaries (of Advaita and Visistadvaita) and their respective sub-commentaries under every adhikarna or chapter.[48] Only the first two chapters of the Brahma Sutra are covered. The rest was completed by Raghunatha Tirtha in the 18th century.[49]

Tarka Tandava

Tarka Tandava or "The Dance of Logic" is a polemical tract targeted towards the Nyaya school. Though Vyasatirtha and his predecessors borrowed the technical language, logical tools and terminologies from the Nyaya school of thought and there is much in common between the two schools, there were significant differences especially with regards to epistemology.[50] Jayatirtha's Nyaya Sudha and Pramana Paddhati were the first reactions against the Nyaya school.[32] The advent of Navya Nyaya widened the differences between the two schools especially related to the acquisition of knowledge or pramanas, triggering a systematic response from Vyasatirtha through Tarka Tandava. Vyasatirtha refers to and critiques standard as well as contemporary works of Nyaya: Gangesha Upadhyaya's Tattvachintamani, Nyayalilavati by Sri Vallabha and Udayana's Kusumanjali and their commentaries. The work is divided into three chapters corresponding to the three pramanas, and a number of topics are raised, including a controversial claim arguing for the supremacy of the conclusion (upasamhara) as opposed to the opening statement (upakrama) of the Brahma Sutra.[51] Purva Mimamsa and Advaita adhere to the theory that the opening statement trumps the conclusion and base their assumptions accordingly. Vyasatirtha's claim put him at odds with the Vedanta community with Appayya Dikshita being his most vocal opponent. Vyasatirtha's claim was defended by Vijayendra Tirtha in Upasamhara Vijaya.[52]

Mandara Manjari

Mandara Manjari is the collective name given to Vyasatirtha's glosses on three (Mayavada Khandana, Upadhi Khandana, Prapancha Mithyavada Khandana) out of Madhva's ten refutation treatises called Dasha Prakarna and one on Tattvaviveka of Jayatirtha. Vyasatirtha here expands only on the obscure passages in the source text.

Bhedojjivana

Bhedojjivana is the last work of Vyasatirtha as it quotes from his previous works. The main focus of this treatise is to emphasise the doctrine of difference (Bheda) in Dvaita as is evident from the title, which can be translated to "Resuscitation of Bheda". Sarma notes "Within a short compass, he has covered the ground of the entire Monistic literature pushed into contemporary prominence and argued an unexpurgated case for the Realism of Madhva".[53]

Legacy

Vyasatirtha is considered to be one of the foremost philosophers of Dvaita thought, along with Jayatirtha and Madhva, for his philosophical and dialectical thought, his role in spreading the school of Dvaita across the subcontinent and his support to the Haridasa movement. Sharma writes "we find in his works a profoundly wide knowledge of ancient and contemporary systems of thought and an astonishingly brilliant intellect coupled with rare clarity and incisiveness of thought and expression".[54] His role as an adviser and guide to the Vijayanagara emperors, especially Krishna Devaraya, has been notable as well.[1]

Spread of Dvaita

_(14255857272).jpg)

Sharma credits Vyasatirtha of converting Dvaita from an obscure movement to a fully realised school of thought of philosophical and dialectical merit.[55] Through his involvement in various diplomatic missions in the North Karnataka region and his pilgrimages across South India, he disseminated the precepts of Dvaita across the sub-continent. By giving patronage to the wandering bards or Haridasas, he oversaw the percolation of the philosophy into the vernacular and as a result into the lives of the lay people. He also contributed to the spread of Dvaita by establishing several Vayu [note 6] idols across Karnataka. Vyasatirtha is also considered a major influence on the then burgeoning Chaitanya movement in modern-day Bengal.[56] Stoker postulates that his polemics against the rival schools of thought also had the effect of securing royal patronage towards Dvaita.[1]

Scholarly Influence

Vyasatirtha was significantly influenced by his predecessors such as Vishnudasacharya, Jayatirtha and Madhva in that he borrowed from their style and method of enquiry. He exerted considerable influence on his successors. Vadiraja's Yuktimalika derives some of its arguments from Nyayamruta,[57] while subsequent philosophers like Vijayendra Tirtha and Raghavendra have authored several commentaries on the works of Vyasatirtha. Vijayadhwaja Tirtha's Padaratnavali, an exhaustive commentary on the Madhva's Bhagvata Tatparya Nirnaya, borrows some its aspects from Vyasatirtha's oeuvre. His influence outside the Dvaita community is found in the works of Appayya, who adopted his doxographical style in some of his works and in the works of Jiva Goswami.[58]

In his dialectics, Vyasatirtha incorporated elements from such diverse schools as Purva Mimamsa, Vyakarana and Navya Nyaya. His criticism of Advaita and Nyaya led to a severe scholarly controversy, generating a series of exchanges between these schools of thought, and led to reformulations of the philosophical definitions of the respective schools. Bagchi notes "It must be recognised that Vyasatirtha's definition of reasoning and his exposition of its nature and service really register a high watermark in the logical speculations of India and they ought to be accepted as a distinct improvement upon the theories of Nyaya-Vaisesika school".[59]

Contributions to the Haridasa Movement

The contribution of Vyasatirtha to the Haridasa cult is two fold: he established a forum of interactions for these bards called Dasakuta and he himself penned several hymns in the vernacular language (Kannada) under the pen name Krishna, most notable of those being the classical Carnatic song Krishna Ni Begane Baaro.[60] Vyasatirtha was also the initiator of social change within the Dvaita order by inducting wandering bards into the mainstream Dvaita movement regardless of caste or creed. This is evident in his initiation of Kanaka Dasa ,[61] who was not a Brahmin and Purandara Dasa[62] who was a merchant.

Political influence

The political influence of Vyasatirtha came into view after the discovery of Vasyayogicharita. The court of Vijayanagara was selective in its patronage thereby creating competition between the sectarian groups.[1] Stoker contends that Vyasatirtha, cognizant of the power of Smartha and the Sri Vaishnava Brahmins in the court, targeted them through his polemical works.[14] Though his works targeted the philosophy of Ramanuja, Vyasatirtha maintained a cordial relationship towards the Sri Vaishnavites, often donating land and money to their temples.[63]

In his role as a diplomat, he interacted with a variety of people including tribal leaders, foreign dignitaries and emissaries from the North India.[64] By establishing mathas and shrines across the subcontinent, patronizing large scale irrigation projects at strategic locations[64] and forging productive relationship across various social groups, he not only furthered the reach of Vaishnavism but smoothed the integration of newly conquered or rebellious territories into the empire.[65] In doing so, he exported the Madhva iconography, doctrines and rituals into the Telgu and Tamil speaking regions of the empire. The establishment of Madhva Mathas, apart from serving as a place of worship and community, led to fostering of economic connections as they also served centers of trade and redistribution of wealth.[66]

Notes

- Quote from Sastri: It was Vyasatirtha, who, for the first time took special pains to collect together from the vast range of Advaitic literature, all the crucial points for discussion and arrange them on a novel, yet thoroughly scientific and systematic plan.[2]

- Quote from Paes: Raya being washed by a Brahmin whom he held sacred and who was a great favourite of his. Sharma conjectures that the washing of the disciple by the guru is found only among the Brahmins adhering to the Madhva tradition (mentioned in Madhva's Tantrasara).[25]

- In 2019, his tomb was dismantled by miscreants in search of a treasure. [31] It was rebuilt the subsequent day by the devotees.

- According to Madhva, there exists five kinds of differences (called panchabheda) in the world. According to this doctrine: 1. no two individual souls or Atmans are alike. 2. Atman and Brahman are distinct and separate 3. Atman is distinct from Matter (called 'jada'). 4. No two particles of matter are alike 5. Brahman and matter are separate and distinct.

- Bhamati, Panchapadika, Vivarana and Kalpataru of the Advaita school, Srutaprakasha and Adhikaranasaravali of the Visistadvaita school and Tattva Prakasika and Nyaya Sudha of the Madhva school.

- Madhva along with Hanuman and Bhima are considered to be the avatars of Vayu.

References

- Stoker 2016, p. 2.

- Sastri 1982, p. 36.

- Dasgupta 1991, p. viii.

- Stoker 2016, p. 24.

- Sharma 2000, p. 252-253.

- Rao 1926, p. xviii.

- Sarma 2007, p. 157.

- Verghese 1995, p. 8.

- Dalmia 2009, p. 158.

- Sharma 1961, p. 255.

- Sharma 1961, p. 183.

- Sharma 2000, p. 330.

- Rao 1959, p. 101.

- Stoker 2016, p. 3.

- Jackson 2000, p. 802.

- Hebbar 2005, p. 93.

- Jackson 2000, p. 902.

- Sharma 2000, p. 26.

- Jackson 2000, p. 903.

- Sharma 2000, p. 27-28.

- Farooqui 2011, p. 121.

- Sarma 2007, p. 156.

- Stoker 2016, p. 29.

- Sharma 2000, p. 29.

- Sewell 2000, p. 249-250.

- Stoker 2016, p. 39-40.

- Stoker 2016, p. 30.

- Sharma 2000, p. 33.

- Karmarkar 1939, p. 40.

- Stoker 2016, p. 78.

- Hindu 2019.

- Williams 2014.

- McCrea 2015.

- Sharma 2000, p. 105-111.

- Nair 1990, p. 20.

- Timalsina 2008, p. 63.

- Timalsina 2008, p. 67.

- Timalsina 2008, p. 10.

- Timalsina 2008, p. 66.

- Sharma 2000, p. 40.

- Lochtefeld 2002, p. 520.

- Sharma 1961, p. 181.

- Nair 1990, p. 21.

- Sharma 2000, p. 145.

- Sharma 2000, p. 150.

- Nair 1990, p. 22.

- Sharma 2000, p. 155.

- Sharma 2000, p. 45.

- Sharma 2000, p. 301.

- Potter 1972, p. 240.

- Sharma 1972, p. 508.

- Sharma 2000, p. 53-54.

- Sarma 1937, p. 15.

- Sharma 2000, p. 97.

- Sharma 2000, p. 103.

- Sharma 2000, p. 104.

- Bhatta 1997, p. 366.

- Vilas 1964, p. 162.

- Bagchi 1953, p. 125.

- Karmarkar 1939, p. 40-42.

- Karmarkar 1939, p. 68.

- Karmarkar 1939, p. 49.

- Stoker 2016, p. 74.

- Stoker 2016, p. 4.

- Stoker 2016, p. 33.

- Stoker 2016, p. 136.

Sources

- Sharma, B.N.K (2000) [1961]. History of Dvaita school of Vedanta and its Literature. 2 (3rd ed.). Bombay: Motilal Banarasidass. ISBN 81-208-1575-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dasgupta, Surendranath (1991). A History of Indian Philosophy, Vol 4. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120804159.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, William (2000). Holy People of the World: A Cross-cultural Encyclopaedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-355-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stoker, Valerie (2016). Polemics and Patronage in the City of Victory. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-29183-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarma, R. Nagaraja (1937). Reign of realism in Indian philosophy. National Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarma, Deepak (2007). Madhvacarya and Vyasatirtha: Biographical sketches of a Systematizer and his Successors. Journal of Vaishnava Studies. pp. 145–168.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verghese, Anila (1995). Religious Traditions at Vijayanagara: As Revealed Through Its Monuments. Manohar. pp. 145–168. ISBN 9788173040863.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rao, Venkoba (1926). Śrī Vyāsayogicaritam: Life of Śrī Vyāsarāja, a Champū Kāvya in Sanskrit by Somanātha. Bangalore: Dvaita Vedanta Studies and Research Foundation.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCrea, Lawrence (2015). Freed by the weight of history: polemic and doxography in sixteenth century Vedānta. South Asian History and Culture, Vol 6. pp. 87–101.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Michael (2014). Mådhva Vedånta at the Turn of the Early Modern Period: Vyåsat rtha and the Navya-Naiyåyikas. International Journal of Hindu Studies. doi:10.1007/s11407-014-9157-7. S2CID 144973134.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sewell, Robert (2000) [1900]. A Forgotten Empire (Vijayanagar): A Contribution to the History of India. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120601253.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sharma, B.N.K (1961). History of Dvaita school of Vedanta and its Literature. 1 (1st ed.). Bombay: Motilal Banarasidass.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dalmia, Vasudha (2009). The Oxford India Hinduism Reader. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-806246-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sastri, N.S Anantakrishna (1982). Advaitasiddhiḥ. Parimala Pablikeśansa.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bagchi, Sitansusekhar (1953). Inductive reasoning: a study of Tarka and its role in Indian logic. Calcutta Oriental Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rao, M.V. Krishna (1959). A Brief Survey of Mystic Tradition in Religion and Art in Karnataka. Wardha Publishing House.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Timalsina, Sthaneshwar (2008). Consciousness in Indian Philosophy: The Advaita Doctrine of 'Awareness Only'. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-97092-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Potter, Karl H. (1972). Thirtieth Anniversary Commemorative Series: Southeast Asia. University of Arizona Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sharma, R. K. (1972). International Sanskrit Conference. The Ministry.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bhatta, C. Panduranga (1997). Contribution of Karaṇāṭaka to Sanskrit. Institute of Asian Studies.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vilas, Bhakti (1964). Sri Chaitanya's Concept of Theistic Vedanta. Sree Gaudiya Math.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Farooqui, Salma Ahmed (2011). A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Pearson Education India. ISBN 9788131732021.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Karmarkar, A. P. (1939). Mystic Teachings of the Haridasas of Karnatak. Karnatak Vidyavardhak Sangha.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nair, K. Maheshwaran (1990). Advaitasiddhi: A Critical Study. Sri Satguru Publications.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lochtefeld, James G. (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism. 2. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hebbar, B.N (2005). The Sri-Krsna Temple at Udupi: The History and Spiritual Center of the Madhvite Sect of Hinduism. Bharatiya Granth Nikethan. ISBN 81-89211-04-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Reconstruction of demolished Brindavana of Vyasaraja begins". Hindu. 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)