Openwork

Openwork or open-work is a term in art history, architecture and related fields for any technique that produces decoration by creating holes, piercings, or gaps that go right through a solid material such as metal, wood, stone, pottery, cloth, leather, or ivory.[2] Such techniques have been very widely used in a great number of cultures.

The term is rather flexible, and used both for additive techniques that build up the design, as for example most large features in architecture, and those that take a plain material and make cuts or holes in it. Equally techniques such as casting using moulds create the whole design in a single stage, and are common in openwork. Though much openwork relies for its effect on the viewer seeing right through the object, some pieces place a different material behind the openwork as a background.

Varieties

Techniques or styles that normally use openwork include all the family of lace and cutwork types in textiles, including broderie anglaise and many others. Fretwork in wood is used for various types of objects. There has always been great use of openwork in jewellery, not least to save on expensive materials and weight. For example, opus interrasile is a type of decoration used in Ancient Roman and Byzantine jewellery, piercing thin strips of gold with punches.[3] Other techniques used casting with moulds, or built up the design with wire or small strips of metal. Essentially flat objects are straightforward to cast using moulds of clay or other materials, and this technique was known in ancient China since before the Shang Dynasty of c. 1600 to 1046 BC.[4] On a larger scale in metal, wrought iron and cast iron decoration more often than not have involved openwork.

Scythian metalwork, which was typically worn on the person, or at least carried about by wagon, uses openwork heavily,[5] probably partly to save weight. Sukashibori (roughly translating to "see-through work") is the Japanese term covering a number of openwork techniques, which have been very popular in Japanese art.[6]

In ceramics, if objects such as sieves are excluded (openwork bases for these existed in the West from classical times), decorative openwork long remained mainly a feature of East Asian ceramics, with Korean ceramics especially fond of the technique from an early date.[7] There was little use of it in European ceramics before the 18th century, when designs, mostly using lattice panels, were popular in rococo ceramic "baskets", and later in English silver trays. Openwork sections can be made either by cutting into a conventional solid body before firing, or by building up using strips of clay, the latter often used when loose wickerwork is being imitated. In glass openwork is rather less common, but the spectacular Ancient Roman cage cups use it for a decorative outer layer.

Some types of objects naturally suit or even require openwork, which allows a flow of air through screens, censers or incense burners, pomanders,[8] sprinklers, ventilation grilles and panels, and various parts of heating systems. For exterior screens openwork designs allow looking out, but not looking in. For gates and other types of screens, security is required, but visibility may also be wanted.

Architecture

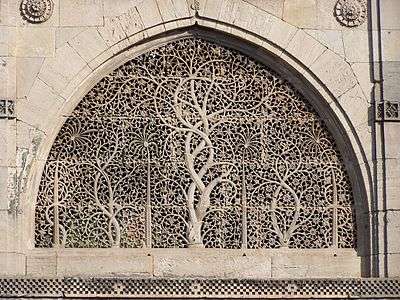

In architecture openwork takes many forms, including tracery, balustrades and parapets, as well as screens of many kinds. A variety of screen types especially common in the Islamic world include stone jali and equivalents in wood such as mashrabiya. Belfries and bell towers normally include open or semi-open elements to allow the sound to be heard at distance, and these are often turned to decorative use. In Gothic architecture some entire spires are openwork. The later of the two spires on the West Front of Chartres Cathedral is very largely openwork. As well as stone and wood the range of materials includes brick, which may be used for windows, normally unglazed, and screens. Constructions such as the Eiffel Tower in Paris are also described as openwork. Here an openwork structure was crucial for the engineering, reducing not only weight but wind resistance.[9]

Beginning with the early fourteenth-century spire at Freiburg Minster, in which the pierced stonework was held together by iron cramps, the openwork spire, according to Robert Bork, represents a "radical but logical extension of the Gothic tendency towards skeletal structure."[10] The 18 openwork spires of Antoni Gaudi's Sagrada Família in Barcelona represent an outgrowth of this Gothic tendency. Designed and begun by Gaudi in 1884, they remained incomplete into the 21st century.

Gallery

Chinese bronze axe head, Shang dynasty

Chinese bronze axe head, Shang dynasty

Celtic ornamental gold mounts, about 420 BC

Celtic ornamental gold mounts, about 420 BC- Bronze Ordos culture plaque, from the eastern end of Scythian art, 4th century BC; a deer attacked by a wolf

Bronze buckle, Georgian, 1st to 4th century AD

Bronze buckle, Georgian, 1st to 4th century AD Japanese canopy ritual banner, gilt-bronze, 7th century

Japanese canopy ritual banner, gilt-bronze, 7th century- Tōdai-ji, 8th century

Anglo-Saxon brooch from the Pentney Hoard

Anglo-Saxon brooch from the Pentney Hoard- Fragrance box with openwork lid, Korea, Goryeo dynasty, 11th–12th century, bronze

Chinese jade ornament with vines, Jin dynasty

Chinese jade ornament with vines, Jin dynasty- Persian incense burner, c. 11th century

French pyx, 1220–1240

French pyx, 1220–1240 Head of an Ethiopian processional cross, 13th or 14th century

Head of an Ethiopian processional cross, 13th or 14th century Ivory casket, Islamic Spain or Egypt, 13th or 14th century

Ivory casket, Islamic Spain or Egypt, 13th or 14th century.jpg)

Chinese wood and lacquer screen

Chinese wood and lacquer screen.jpg) Steel plaque from Iran. One of a set of 8, probably for fixing to wood, perhaps in a royal tomb, 17th century

Steel plaque from Iran. One of a set of 8, probably for fixing to wood, perhaps in a royal tomb, 17th century- Openwork Hexagonal Ko-Kiyomizu Ware Bowl, c. 1731–1752, Japan, artist unknown, stoneware with overglaze enamels

- American chair, 1760–80, to a design by Thomas Chippendale

- Lotus-shaped cup with openwork handle, China, probably 19th century AD, rhinoceros horn

Japanese tsuba, early 19th century

Japanese tsuba, early 19th century.jpg) African dancer's headpiece, wood

African dancer's headpiece, wood.jpg) Detail of handkerchief in button-hole embroidery. Germany or Switzerland, 19th century.[11]

Detail of handkerchief in button-hole embroidery. Germany or Switzerland, 19th century.[11]

Architecture gallery

At Borobudor hundreds of Buddha statues sit inside openwork stupas; here the nearest is partly deconstructed

At Borobudor hundreds of Buddha statues sit inside openwork stupas; here the nearest is partly deconstructed.jpg) West front of Chartres cathedral. The tower on the left is largely openwork

West front of Chartres cathedral. The tower on the left is largely openwork The secondary spires at Freiburg Minster

The secondary spires at Freiburg Minster- Window in the Alhambra

Hardwick Hall, England, 1590s

Hardwick Hall, England, 1590s Brick windows on an Austrian barn

Brick windows on an Austrian barn Gothic Revival balustrade in Germany

Gothic Revival balustrade in Germany Cast iron bracket for a gas lamp, Vienna

Cast iron bracket for a gas lamp, Vienna

See also

References

- British Museum Ref:1994,0408.29

- "Openwork." Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed May 26, 2015, subscription required. Their article reads, in full: "Any form of decoration that is perforated". OED "Openwork", 1, where all examples cited from earlier than 1894 are hyphenated, though this is now less common than the single word.

- Diane Favro, et al. "Rome, ancient, s 5, ii." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed May 27, 2015, subscription required

- Department of Asian Art. "Shang and Zhou Dynasties: The Bronze Age of China". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2004)

- Timothy Taylor. "Scythian and Sarmatian art." Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed May 27, 2015, subscription required

- Tokyo National Museum (1976). 和英対照日本美術鑑賞の手引(An Aid to the Understanding of Japanese Art). pp. 132/133.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (revised edition; 1964 first ed.), p.132/133

- Whitfield, Roger (ed), Treasures from Korea: Art Through 5000 Years, p. 68, 1984, British Museum Publications, ISBN 0-7141-1430-8, 9780714114309. Openwork bases and pedestals "became the characteristic and dominant forms in ceramics" in the Gaya confederacy period.

- Aftel, mandy, Fragrant: The Secret Life of Scent, 2014, Penguin, ISBN 1101614684, 9781101614686, p. 129

- Harriss, Joseph (1975). The Eiffel Tower:Symbol of an Age. London: Paul Elek. p. 63. ISBN 0236400363.

- Robert Bork, "Into Thin Air: France, Germany, and the Invention of the Openwork Spire" The Art Bulletin 85.1 (March 2003, pp. 25–53), p 25.

- The whole piece, LACMA

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Openwork. |