Bashkirs

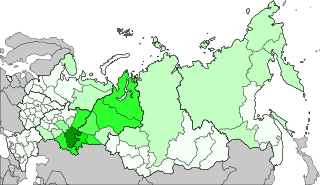

The Bashkirs (/ˈbɑːʃkɪərz/; Bashkir: Башҡорттар, IPA: [bɑʂqʊrtˈtɑr]; Russian: Башкиры, pronounced [bɐʂˈkʲirɨ]) are a Turkic ethnic group, indigenous to Bashkortostan and the historical region of Badzhgard. This area extends both sides of the Ural Mountains where Eastern Europe meets North Asia. Smaller communities of Bashkirs also live in the Republic of Tatarstan, Perm Krai, Chelyabinsk, Orenburg, Tyumen, Sverdlovsk, Kurgan Oblasts and other regions of Russia. Bashkirs also reside in Kazakhstan and other countries.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approx. 2 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,584,554[2] |

| 17,263[3] | |

| 47,000[4] | |

| 4,253[5] | |

| 1,200[6] | |

| 3,820[7] | |

| 610[8] | |

| 230[9] | |

| 136[5] | |

| 112[10] | |

| 1,111[11] | |

| 379[12] | |

| 533[13] | |

| 145[14] | |

| 8,400[15] | |

| Languages | |

| Bashkir, Russian[16] | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam[17] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Turkic peoples, especially Tatars and Chuvash | |

Most Bashkirs speak the Bashkir language, closely related to the Tatar and Kazakh languages which belong to the Kipchak branch of the Turkic languages. Cultural affinities are shared with the broader Turkic peoples. Religiously, the Bashkirs are mainly Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi madhhab faith.

The Bashkir people are subject to systematic Russification and discrimination. They lack the opportunity to study in their native language at school as well as at university.[18][19][20] The Bashkir language is included in the list of endangered languages.[21]

Ethnonym

The etymology and indeed meaning of the endonym Bashqort is without consensus. The following theories of origin and definition have been advanced:

- The 18th-century ethnographers V. N. Tatishchev, P. I. Richkov, and Johann Gottlieb Georgi, according to a recorded folk etymology, the word Bashqort, originally meant: "wolf leader" (i.e. bash "head" and qort "wolf").

- In 1847, the historian V. S. Yumatov suggested the original meaning to be: "beekeeper, beemaster".

- Historian and ethnologist A. E. Alektorov (1885) suggested that Bashqort meant "distinct nation".

- Anthropologist R. M. Yusupov considered Bashqort may have originally been an Iranian compound word meaning: "wolf-children" or "descendants of heroes", i.e. bacha "descendant, child" and gurd "hero" or gurg "wolf".

- Historian and archaeologist Mikhail Artamonov suggested that the word is a corruption of the name of the Bušxk' (or Bwsxk), a Scythian tribe speaking Iranian-that lived in the area now known as Bashkortostan.[22]

- The Turkologist N. A. Baskakov believed the term: "Bashqort" to have consisted of two parts: "badz(a)" – brother-in-law" and "(o)gur" meaning: "brothers-in-law of the Ugor [Magyars]".

- According to the orientalist Douglas Morton Dunlop, the ethnonym Bashqort was derived from beshgur (or bashgur) which means "five tribes in modern Bashkir language.

- Ethnologist N. V. Bikbulatov suggested that the term originated from the name of a legendary Khazar warlord named Bashgird, who ruled an area centred on the Jayıq river.

- Ethnologist R. G. Kuzeev derived the ethnonym from a compound of "bash" — "main, head" and "qort" — " clan, tribe".

- Historian and linguist András Róna-Tas argued the ethnonym "Bashkir" to be a Bulgar Turkic reflex of the Hungarian endonym Magyar (or the Old Hungarian Majer).

History

Origins

The Bashkirs are considered to have some cultural similarities to Iranian tribes who formerly existed in modern Bashkortostan, such as the Bušxk', and may have descended from them.[23] Alternatively, Mikhail Artamonov suggested Bashkirs are descended from the Bušxk', a Scythian tribe that became culturally "Turkified" (including a process of language replacement), during the Turkic migrations of the first millennium AD.[22]

Middle ages

The first report about Bashkirs might have been found in the Chinese chronicle Book of Sui: around 40 Turkic Tiele tribes were named (636 AD) in "A Narration about the Tiele people"; Bashkirs might have included within that narration: if the tribal name 比干 (Mandarin Bǐgān < Middle Chinese ZS: *piɪX-kɑn) were read as 比千 (Bĭqiān < *piɪXt͡sʰen), according to Chinese scholar Rui Chuanming[24]

In the 7th century, Bashkirs are also mentioned in "Ashkharatsuyts".

From the 9th century, the first Arab and Persian written reports about Bashkirs commence. These include reports by:: Sallam al-Tardzhuman (9th century).

10th-century authors on the Bashkir were: Ahmad ibn Fadlan, Al-Masudi, and Abu Zayd al-Balkhi.

In the 12th century, Said Al-Andalusi and Muhammad al-Idrisi mentioned the Bashkirs. The 13th-century authors Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi, Yaqut al-Hamawi and Qazvini and the 14th-century authors Al-Dimashqi and Abu'l-Fida wrote about Bashkirs.

The traveller Sallam an at-Tardzhuman visited Bashkir lands and wrote in circa 840 the first written Arab source on the Bashkirs and a rough description of its borders. In the 10th century, Persian Abu Zayd al-Balkhi (10th century) described Bashkirs as a people divided into two groups: one inhabiting the Southern Urals, the other living on the Danube plain near the boundaries of Byzantium. Ibn Rustah, a contemporary of Abu Zayd al-Balkhi, observed that Bashkirs were an independent people occupying territories on both sides of the Ural mountains ridge between Volga, Kama, and Tobol Rivers and upstream of the Yaik river.

Ahmad ibn Fadlan, ambassador of the Baghdad Caliph Al-Muqtadir to the governor of Volga Bulgaria, wrote the first ethnographic description of the Bashkir in 922. The Bashkirs, according to Ibn Fadlan, were a warlike and powerful people, which he and his companions (a total of five thousand people, including military protection) "bewared... with the greatest threat". They were described as engaged in cattle breeding. According to ibn Fadlan, the Bashkirs worshipped twelve gods: winter, summer, rain, wind, trees, people, horses, water, night, day, death, heaven and earth, and the most prominent, the sky god. Apparently, Islam had already begun to spread among the Bashkirs, as one of the ambassadors was a Muslim Bashkir. According to the testimony of Ibn Fadlan, the Bashkirs were Turks, living on the southern slopes of the Urals, and occupying a vast territory up to the river Volga. They were bordered by Oghuz Turks on the south, Pechenegs to the south-east and Bulgars on the west.

The first European sources to mention the Bashkirs were the works of Joannes de Plano Carpini and William of Rubruquis of the 13th century.

By 1236, Genghis Khan had incorporated the lands of Bashkortostan were incorporated into his empire. During the 13th and 14th centuries, all of Bashkortostan was a component of the Golden Horde. The brother of Batu-Khan, Sheibani, received the Bashkir lands east of the Ural Mountains.

After the disintegration of the Mongol Empire, the Bashkirs were divided among the Nogai Horde, the Khanate of Kazan and the Khanate of Sibir, founded in the 15th century.

Early modern period

In the middle of the 16th century, Bashkirs were gradually conquered by the Tsardom of Russia.[25] Primary documents pertaining to the Bashkirs during this period have been lost, although some are mentioned in the shezhere (family trees) of the Bashkir.

During the Russian Imperial period, Russians and Tatars began to migrate to Bashkortostan which led to eventual demographic changes in the region. The recruitment of Bashkirs into the Russian army and having to pay steep taxes pressured many Bashkirs to adopt a more settled lifestyle and to slowly abandon their ancient nomadic pastoralist past.[25]

In the late 16th and early 19th centuries, Bashkirs occupied the territory from the river Sylva in the north; to the river heads of Tobol in the east; the mid-stream of the river Yaik in the south; in the Middle and Southern Urals, the Cis-Urals including Volga territory and Trans-Uralsto; and the eastern bank of the river Volga on the south-west.

Bashkir rebellions of the 17th–18th centuries

The Bashkirs participated in the 1662–64, 1681–84 and 1704–11 Rebellions. In 1676, the Bashkirs rebelled under a leader named Seyid Sadir or 'Seit Sadurov', and the Russian army had great difficulties in ending the rebellion. The Bashkirs rose again in 1707, under Aldar and Kûsyom, due to perceived ill-treatment by Imperial Russian officials.

At the founding of Orenburg in 1735, the fourth insurrection occurred in 1735 and lasted six years. Russians had discussed from the times of Peter the Great a desire to expand Russian sovereignty south-east toward Persia and India. Ivan Kirillov formed a plan to build the fort to be called Orenburg at Orsk at the confluence of the Or River and the Ural River, south-east of the Urals where the Bashkir, Kalmyk and Kazakh lands met. Work on Fort Orenburg commenced at Orsk in 1735. However, by 1743 'Orenburg' was moved a further 250 km west to its current location. The next planned construction was to be a fort on the Aral Sea. The consequence of the Aral Sea fort would involve crossing Bashkir and the Kazakh Lesser Horde lands, some of whom had recently offered a nominal submission to the Russia Crown.

Kirillov's plan was approved on May 1, 1734 and he was placed in command. Although Kirillov was warned that this may provoke a Bashkir rebellion, the warnings were ignored. Kirillov left Ufa with 2,500 men in 1735.

Warfare commenced on the first of July, 1735. The war consisted of many small raids and complex troop movements, so it cannot be easily summarized.

For example: In the spring of 1736, Kirillov burned 200 villages, killed 700 in battle and executed 158. An expedition of 773 men left Orenburg in November and lost 500 from cold and hunger. At Seiantusa the Bashkir planned to massacre sleeping Russians, however, the ambush failed. In retaliation, one thousand villagers, including women and children, were put to the sword and another 500 driven into a storehouse and burned to death. Raiding parties then went out and burned about 50 villages and killed another 2,000. Eight thousand Bashkirs attacked a Russian camp and killed 158, losing 40 killed and three Bashkir prisoners were promptly hanged by the Russians. Rebellious Bashkirs raided loyal Bashkirs. Leaders who submitted were sometimes fined one horse per household and on other occasions, hanged. Kirillov died of disease during the war and there were several changes of commander. The Baskir War occurred during the reign of Empress Anna of Russia and the Russo-Turkish War (1735–1739).

Although the history of the 1735 Bashkir War cannot be easily summarized, its results can be.

- The Russian Imperial goal of expansion into Central Asia was delayed to deal with the Bashkir problem.

- Bashkiria was pacified in 1735–1740.

- Orenburg was established.

- The southern side of Bashkiria was partitioned by the Orenburg Line of forts. The forts ran from Samara on the Volga east as far as the Samara River headwaters.. It then crossed to the middle of the Ural River and following the river course east and then north on the eastern side of the Urals. It then went east along the Uy River to Ust-Uisk on the Tobol River where it connected to the ill-defined 'Siberian Line' along the forest-steppe boundary.

- In 1740 a report was made of Bashkir losses which listed: Killed: 16,893; sent to Baltic regiments and fleet: 3,236; women & children distributed (presumably as serfs): 8,382 with a grand total of 28,511. Fines were reported as: horses: 12,283; cattle and sheep: 6,076; money: 9,828 rubles; villages destroyed: 696. The compilation was from army reports and excluded losses from irregular raiding, hunger, disease and cold. At the time, the Bashkir population was estimated at 100,000.

Next major rebellion occurred in 1755–56. In its suppression, 36,000 Russian regular troops were involved. The number of rebels was about 50,000. The rebellion was cruelly crushed.

Later, in 1774, the Bashkirs, under the leadership of Salavat Yulayev, supported Pugachev's Rebellion. In 1786, the Bashkirs achieved tax-free status; and in 1798 Russia formed an irregular Bashkir army from among them. Residual land ownership disputes continued.

There are many museums in the Republic where you can get acquainted with the history of the region. The National Museum of the Republic of Bashkortostan, the Bashkir Nesterov Art Museum , the Museum of Archeology and Ethnography are the largest of them.

Napoleonic Wars

During the Napoleonic Wars, many Kalmyks and Bashkirs served in the Russian army to defend the Russian nation from the French invaders during Napoleon's invasion of Russia. [26] Many Bashkir regiments served in Battle of Paris and the subsequent occupation of France by the coalition forces.[27]

The establishment of the Republic of Bashkortostan

After the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the All-Bashkir Qoroltays (convention) concluded that it was necessary to form a national federal Bashkir republic within Russia. As a result, on 15 November 1917, the Bashkir Regional (central) Shuro (Council) proclaimed the establishment of the Bashkir republic in areas of predominantly Bashkir population: Orenburg, Perm, Samara, Ufa provinces and the autonomous entity Bashkurdistan.

In December 1917, delegates to the All-Bashkir (constituent) Congress, representing the interests of the population edge of all nationalities, voted unanimously for the Resolution (Farman #2) of the Bashkir regional Shuro on the proclamation of national-territorial autonomy (of the republic) Bashkurdistan. From the Congress, the government of Bashkurdistan, the Pre-parliament – Kese-Qoroltay and other bodies of power and administration, were formed and decisions made on how next to proceed.

In March 1919, the Bashkir Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was formed based on agreements of the Russian Government.

On October 11, 1990 Declaration of State Sovereignty by the Supreme Council of the Republic was proclaimed. On March 31, 1992 Bashkortostan signed a federal agreement on the delimitation of powers and areas of jurisdiction and the nature of contractual relations between the authorities of the Russian Federation and the authorities of the sovereign republics in its composition including the Republic of Bashkortostan.

Great Patriotic War

During World War II, Bashkir soldiers served in the Red Army to defend the Soviet Union and fought against the Germans during the German invasion of the Soviet Union.[28][29]

Genetics

The modern Bashkirs have an average of approximately 60% "West-Eurasian/European" and 40% "Siberian/East-Asian" genetic material.[30]

Genetic studies have revealed Y-DNA haplogroups the dominant frequency for Bashkir males is the haplogroup R1b (R-M269 and R-M73) which is, on average, 47.6%. The Y-DNA haplogroup R-M269 (R1b1a2) R-M269 is the most common European haplogroup, greatly increasing in frequency on a West to East its prevalence in Wales at 92.3% to Poland estimated at 22.7%.

The second most dominant is the haplogroup R1a at an average frequency of 26,5%, and third the haplogroup N1c at 17%. Despite the Bashkirs being considered a Turkic peoples, DNA haplogroups R1a and R1b are majority shared with Indo-Europeans.

Haplogroups J2, C, O, E1b, G2a, L, N1b, I, T.were found at lower incidences.[31]

Most mtDNA haplogroups of the Bashkirs (60–65%) consist of the haplogroups G, D, С, Z and F; which are lineages characteristic of East-Eurasian populations. On the other hand, mtDNA haplogroups characteristic of European and Near Eastern populations were found in significant amounts (35–40%).[32][33][34] Immunogeneticist Suslova commented in 2015 that:

The Bashkirs appear close to Mongoloids in allele and haplotype distribution. However, Bashkirs cannot be labelled either as typical Mongoloids or as Caucasoids. Thus, Bashkirs possess some alleles and haplotypes frequent in Mongoloids, which supports the Turkic impact on Bashkir ethnogenesis, but also possess the AH 8.1 haplotype, which could evidence an ancient Caucasoid population that took part in their ethnic formation... Bashkirs showed no features of populations with a substantial Finno-Ugric component, for example, Chuvashes or Russian Saami. This disputes the commonly held belief of a Finno-Ugric origin for Bashkirs...

— Suslova et al. 2015, International Journal of Immunogenetics

The Bashkirs are characterized by East-Asian admixture, which dates from the 13th century, according to an analysis of the identical-by-descent segments.[35]

A group of Bashkirs from the Burzyansky and Abzelilovsky districts of the Republic of Bashkortostan in the Volga-Ural region who belong to the R1a subclade R-SUR51 are the closest kin of the Hungarian Árpád dynasty, from which got separated 2000 years ago.[36]

Language

Bashkir language is a Turkic language of the Kypchak group. It has three main dialects: Southern, Eastern and North-Western located in the territory of Historical Bashkortostan.

The Russian census of 2010 recorded 1,152,404 Bashkir speakers in the Russian Federation. Bashkir language is native to 1 133 339 Bashkirs (71,7% of the total number of Bashkirs, reporting mother tongue). The Tatar language was reported as native tongue to 230,846 Bashkirs (14,6%). and Russian language reported as native tongue to 216 066 Bashkir (13,7%). Most Bashkirs are bilingual in Bashkir and Russian.

The Bashkir tribes of pre-Islamic conversion used the Old Turkic alphabet. After the adoption of Islam, which began in the 10th century and lasted for several centuries, the Bashkirs began to use the Arabic alphabet. From the mid-18th-century Bashkir national literature began to be formulated. In 1923, Bashkir alphabet was based on the Arabic alphabet. In 1929 a Latin alphabet (yanalif) form of transcribing Bashkir was formulated. In 1940, writing Bashkir in Cyrillic alphabet was formulated. The modern Bashkir alphabet consists of 42 letters.

The Bashkir language was considered endangered but recent Bashkir nationalism has made many develop an interest in it. The combination of encouragement by local authorities and renewed Bashkir language interest among Bashkirs have greatly assisted the language to stay relevant.[25]

Demographics

The ethnic Bashkir population is estimated at roughly 2 million people (2009 SIL Ethnologue). The 2010 Russian census recorded 1,584,554 ethnic Bashkirs in Russia, of which 1,172,287 Bashkirs live in Bashkortostan (29.5% of the total population of the republic).

Culture

The Bashkirs traditionally practiced agriculture, cattle-rearing and bee-keeping. The half-nomadic Bashkirs wandered either the mountains or the steppes, herding cattle. Wild-hive beekeeping can be named as a separate component of the most ancient culture which is practiced in the same Burzyansky District near to the Kapova Cave.[25]

Traditional Bashkir dish bishbarmaq is prepared from boiled meat and halma (the kind of noodles), sprinkled with herbs flavored with onions and some qorot (young dry cheese). This is another notable feature of the Bashkir cuisine: dishes often served dairy products — rare party without qorot or qaymaq (sour cream). Most of the dishes Bashkir cuisine is nutritious and easy to prepare.

A series of epic Bashkir works called Ural-batyr and Akbuzat keeps layers of ancient mythology and have parallels with the Epic of Gilgamesh, Rigveda, and Avesta. Their plots concern the struggle of heroes against demonic forces. A peculiarity of them is that events and ceremonies described there may reference a specific geographical place; the Shulgan-Tash cave and its vicinity.

Religion

.jpg)

In the pre-Islamic period the Bashkirs were followers of Animism, Shamanism and Tengrianism.[37][38]

Bashkirs began converting to Islam in the 10th century.[39][25] Arab traveler Ibn Fadlan in 921 met some of the Bashkirs, who were already Muslims.[40] The final assertion of Islam among the Bashkirs occurred in the 1320s and 1330s during the Golden Horde period. The mausoleum of Hussein-Bek, the burial place of the first Imam of Historical Bashkortostan, is preserved in Bashkortostan. The mausoleum is a 14th-century building. Catherine the Great established the Orenburg Mohammedan Spiritual Assembly in 1788 in Ufa, which was the first Muslim administrative center in Russia.

Religious revival among the Bashkirs began in the early 1990s.[41] According to Talgat Tadzhuddin there were more than 1,000 mosques in Bashkortostan in 2010.[42]

The Bashkirs are predominantly Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi madhhab.[17]

Notable Bashkirs

- Salawat Yulayev, Bashkir national hero

- Zeki Velidi Togan, historian, turkologist and leader of the Bashkir national movement of the early 20th century

- Shaikhzada Babich, Bashkir poet, writer and playwright. Member of the Bashkir national liberation movement, one of the members of the Bashkir government (1917–1919)

- Shagit Hudayberdin, Communist revolutionary

- Tagir Kusimov, Soviet military leader

- Mustai Karim, Bashkir Soviet poet, writer and playwright. He was named People's poet of the Bashkir Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (1963), Hero of Socialist Labour (1979), and winner of the Lenin Prize (1984) and the State Prize of the USSR (1972)

- Zagir Ismagilov, composer and educator

- Murtaza Rakhimov, first president of Bashkortostan

- Lyasan Utiasheva, (Bashkir mother) TV show host, socialite and former rhythmic gymnast

- Alina Ibragimova Violinist

See also

References

- Lewis, M. Paul (ed.) (2009). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition". Dallas, Tex.: SIL International.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "ВПН-2010". Perepis-2010.ru. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

- Archived September 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Population by national and/or ethnic group, sex and urban/rural residence: each census, 1985—2003

- "Итоги всеобщей переписи населения Туркменистана по национальному составу в 1995 году". Archived from the original on 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- Демоскоп. МССР. 1989

- PCE04: ENUMERATED PERMANENT RESIDENTS BY ETHNIC NATIONALITY AND SEX, 31 DECEMBER 2011

- [Национальный статистический комитет Кыргызской Республики. Численность постоянного населения по национальностям по переписи 2009 года]

- Демоскоп. Груз. ССР 1989

- Демоскоп. Аз. ССР 1989

- "8. НАСЕЛЕНИЕ НАИБОЛЕЕ МНОГОЧИСЛЕННЫХ" (PDF). Gks.ru. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

- "Bashkortostan and Bashkirs", Encyclopedia.com

- Mikhailov, Valentin. "Political, social and ethnic protests in Bashkortostan and Tatarstan." In Systemic and Non-Systemic Opposition in the Russian Federation, pp. 163–188. Routledge, 2016.

- Gizatova, Guzel. "A nation without a language is a nation without heart." Language Endangerment: Disappearing metaphors and shifting conceptualizations 7 (2015): 175.

- Simon, Gerhard. Nationalism and policy toward the nationalities in the Soviet Union: From totalitarian dictatorship to post-Stalinist society. Routledge, 2019.

- Wurm, Stephen A. Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger of Disappearing. Unesco, 2001.

- Peter B. Golden, Haggai Ben-Shammai & András Róna-Tas, The World of the Khazars: New Perspectives, Leiden/Boston, Brill, 2007, pp. 422.

- Maria Magdolna Tatár, “The Myth of Macha in Eastern Europe”, The Journal of Indo-European Studies vol. 35, no. 3 & 4, Fall/Winter 2007, p. 325.

- Cheng, Fangyi. "The Research on the Identification Between Tiele and the Oghuric Tribes": 83-84. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Skutsch, Carl, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. New York: Routledge. pp. 188, 189. ISBN 1-57958-468-3.

- Vershinin, Alexander; RIR, specially for (2014-07-29). "How Russia's steppe warriors took on Napoleon's armies". www.rbth.com. Retrieved 2020-01-14.

- Vershinin, Alexander; RIR, specially for (2014-07-29). "How Russia's steppe warriors took on Napoleon's armies". www.rbth.com. Retrieved 2020-01-14.

- "Loading..." bashforum.net. Archived from the original on 2 July 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- Ibragimov, N. G. (1988). "[Public and private aid to evacuated hospitals in the Bashkir ASSR during the years of the war]". Sovetskoe Zdravookhranenie (3): 64–67. ISSN 0038-5239. PMID 3287647.

- "Bashkir Genetics - DNA of Russia's Turkic people of Bashkortostan". www.khazaria.com. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- Лобов А. С. Структура генофонда субпопуляций башкир. Диссертация кандидата биологических наук. — Уфа, 2009.- 131 с. Archived 2011-08-16 at the Wayback Machine

- С. А. Лимборская, Э. К. Хуснутдинова, Е. В. Балановская. Этногеномика и геногеография народов Восточной Европы. Институт молекулярной генетики РАН. Уфимский научный центр. Медико-генетический научный центр РАМН. М. Наука. 2002. С.179–180

- Антропология башкир/Бермишева М. А., Иванов В. А., Киньябаева Г. А. и др. СПб., Алетейя, 2011, 496 с., С.339.

- "Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA Lineages in Yakuts" (PDF).

- Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg; Turdikulova, Shahlo; Dalimova, Dilbar; Nymadawa, Pagbajabyn; Bahmanimehr, Ardeshir; Sahakyan, Hovhannes; Tambets, Kristiina; Fedorova, Sardana; Barashkov, Nikolay; Khidiyatova, Irina; Mihailov, Evelin; Khusainova, Rita; Damba, Larisa; Derenko, Miroslava; Malyarchuk, Boris; Osipova, Ludmila; Voevoda, Mikhail; Yepiskoposyan, Levon; Kivisild, Toomas; Khusnutdinova, Elza; Villems, Richard (21 April 2015). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLOS Genet. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

- Nagy, P.L.; Olasz, J.; Neparáczki, E.; et al. (2020), "Determination of the phylogenetic origins of the Árpád Dynasty based on Y chromosome sequencing of Béla the Third", European Journal of Human Genetics, doi:10.1038/s41431-020-0683-z

- Shireen Hunter, Jeffrey L. Thomas, Alexander Melikishvili, "Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security", M.E. Sharpe Inc.

- К вопросу о тенгрианстве башкир // Compatriot, Popular Science Magazine (in Russian)

- Shirin Akiner, "Islamic Peoples Of The Soviet Un", Second edition, 1986

- Allen J. Frank, "Islamic Historiography and "Bulghar" Identity Among the Tatars and Bashkirs", Brill, 1998

- Jeffrey E. Cole, "Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia", Greenwood publishing group

- Интерфакс. Говорить о притеснении ислама в России кощунственно, считает Талгат Таджуддин // Interfax, 17 December 2010

Further reading

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Rudenko, S. I. (2006). Башкиры: историко-этнографические очерки [The Bashkirs: historical and ethnographic essays] (in Russian). Ufa: Kitap. ISBN 5-295-03899-8.

- Kuzeev, R. G. (2010). Происхождение башкирского народа. Этнический состав, история расселения [The origin of the Bashkir people. Ethnic composition, history of settlement] (in Russian). Ufa: DizainPoligrafServis. ISBN 978-5-94423-212-0.

- Bermisheva, M. A.; Ivanov, V. A.; Kinyabaeva, G. A.; et al. (2011). Антропология башкир [Anthropology of the Bashkirs] (in Russian). Saint-Petersburg: Aleteya. ISBN 978-5-91419-386-4.

- Kulsharipov, M. M., ed. (2009). История башкирского народа: в 7 т. Т. I [History of the Bashkir people: 7 vol. Vol. I] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. ISBN 978-5-02-037010-4. Archived from the original on 2017-03-06. Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- Kulsharipov, M. M., ed. (2012). История башкирского народа: в 7 т. Т. II [History of the Bashkir people: 7 vol. Vol. II] (in Russian). Ufa: Gilem. ISBN 978-5-91608-100-8. Archived from the original on 2017-03-21. Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- Kulsharipov, M. M., ed. (2011). История башкирского народа: в 7 т. Т. III [History of the Bashkir people: 7 vol. Vol. III] (in Russian). Ufa: Gilem. ISBN 978-5-7501-1301-9.

- Kulsharipov, M. M., ed. (2011). История башкирского народа: в 7 т. Т. IV [History of the Bashkir people: 7 vol. Vol. IV] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. ISBN 978-5-02-038276-3.

- Kulsharipov, M. M., ed. (2009). История башкирского народа: в 7 т. Т. V [History of the Bashkir people: 7 vol. Vol. V] (in Russian). Ufa: Gilem. ISBN 978-5-7501-1199-2. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- Kulsharipov, M. M., ed. (2009). История башкирского народа: в 7 т. Т. VI [History of the Bashkir people: 7 vol. Vol. VI] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. ISBN 978-5-02-036494-3. Archived from the original on 2017-01-15. Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- Kulsharipov, M. M., ed. (2012). История башкирского народа: в 7 т. Т. VII [History of the Bashkir people: 7 vol. Vol. VII] (in Russian). Ufa: Gilem. ISBN 978-5-4466-0040-3. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- Asfandiyarov, A. Z., ed. (2013). Военная история башкир: энциклопедия [Military history of Bashkirs: Encyclopedia] (in Russian). Ufa: Bashkir encyclopedia. ISBN 978-5-8818-5076-0.

- Kuzeev, R. G.; Danilko, E. S., eds. (2015). Башкиры [The Bashkirs] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. ISBN 978-5-02-039182-6.

- Ilgamov, M.A., ed. (2015–2016). Башкирская энциклопедия: в 7 томах [Bashkir encyclopedia: 7 vol.] (in Russian). Ufa: Bashkir encyclopedia. ISBN 978-5-88185-306-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bashkir people. |

- Photos of Bashkirs and their life in funds of the Library of Congress

- Photos of Bashkirs and their life in funds of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (the Kunstkamera)