5th Division (Australia)

The 5th Division was an infantry division of the Australian Army which served during the First and Second World Wars. The division was formed in February 1916 as part of the expansion of the Australian Imperial Force infantry brigades. In addition to the existing 8th Brigade were added the new 14th and 15th Brigades, which had been raised from the battalions of the 1st and 2nd Brigades respectively. From Egypt the division was sent to France and then Belgium, where they served in the trenches along the Western Front until the end of the war in November 1918. After the war ended, the division was demobilised in 1919.

| Australian 5th Division | |

|---|---|

A machine gun position established by the 54th Battalion during its attack on German forces at Peronne, France, 1 September 1918. | |

| Active | 1916–1919 1939–1945 |

| Country | |

| Branch | Australian Army |

| Size | Division |

| Part of | II ANZAC Corps (World War I) II Corps (World War II) |

| Engagements | World War I |

| Insignia | |

| Unit Colour Patch |  |

The division was re-raised as a Militia formation during the Second World War, and was mobilised for the defence of North Queensland in 1942, when it was believed that the area was a prime site for an invasion by Japanese forces. Most of the division was concentrated in the Townsville area, although the 11th Brigade was detached for the defence of Cairns and Cape York. In 1943, the division took part in the final stages of the Salamaua–Lae campaign, in New Guinea, and then later in 1944 captured Madang during the Huon Peninsula campaign. In 1944–1945, the division was committed to the New Britain campaign, before being relieved in July 1945. The division was disbanded in September 1945 following the end of the war.

First World War

Formation in Egypt, 1916

In early 1916, following the unsuccessful Gallipoli campaign, the Australian government decided to expand the size of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF).[4] At the time there were two Australian divisions in Egypt: the 1st and 2nd. The 3rd Division was raised in Australia,[5] while the 1st Division was split up to provide a cadre upon which to raise the 4th and 5th Divisions.[6] The 14th and 15th Brigades were formed from the 1st and 2nd Brigades, while the division's third brigade, the 8th, was formed from unassigned personnel that had arrived in Egypt as reinforcements and were unattached at divisional level.[7] On formation at Tel el Kebir in February 1916, the 5th Division joined II Anzac Corps, and its main element was its three infantry brigades: the 8th, 14th and 15th.[1] Upon formation, each brigade consisted of around 4,000 personnel, organised into four infantry battalions.[8]

When the more experienced I Anzac Corps embarked for France at the end of the month, they took most of the available artillery pieces and trained artillery personnel, leaving the II Anzac divisions to train new artillery batteries from scratch, a process that would take three months.[9] Major-General James McCay, formerly commander of the Australian 2nd Infantry Brigade, assumed command of the division on 21 March 1916,[10] after returning from Australia, having been wounded during the Gallipoli campaign.[11][12]

After the dispatch of the 1st and 2nd Divisions to France, responsibility for the defence of the Suez Canal against an expected Turkish attack passed to the remaining two Australian divisions. The 5th Division was allocated to the defence of the canal around Ferry Post. Moving by train to Moascar, and then by foot to Ferry Post, the 8th Brigade moved in to position by 27 March. Meanwhile, the remainder of the division's infantry – the 14th and 15th Brigades – were to complete the move on foot, a march of 57 kilometres (35 mi) from the Anzac camp at Tel el Kebir. McCay voiced some concerns about the march to his superiors, but followed the order and his actions during the march, and words afterwards, later soured relations between the divisional commander and the soldiers.[13] Taking three days over soft sand and in extreme heat (with temperatures up to 100 °F (38 °C)[13]) the men in the two brigades suffered severely and the march was completed in disarray with many suffering heat illness; many were helped in from the desert by a neighbouring New Zealand unit who volunteered to provide assistance upon learning of the situation.[12][14]

Throughout late March to the end of May, concurrently with completing the process of training and equipping,[15] the division's brigades rotated through the positions forward of Ferry Post. Finally, at the end of the month, the British 160th Brigade arrived, relieving the Australians.[16] Throughout June, the division returned to Moascar, where reinforcements were received to bring units up to their authorised strengths in preparation for their transfer to Europe, to join the fighting on the Western Front. In the middle of the month, they moved by train to Alexandria and embarked on a number of troopships.[17]

Fromelles, 1916

The 5th Division began arriving in France in late June 1916, landing in Marseilles,[18] the last of the four Australian divisions from Egypt to do so (although the 3rd Division, which sailed from Australia, arrived last in February 1917).[19] At this time the Battle of the Somme was underway and going badly for the British. The divisions of I Anzac Corps, which had been acclimatising in the quiet sector near Armentières since April 1916,[20] had been dispatched to the Somme as reinforcements, and so the 4th and 5th Divisions, which formed part of II Anzac Corps under Lieutenant General Alexander Godley,[21] took their place at Armentières.[22] The 4th Division subsequently occupied the front, while the 5th Division remained in reserve, completing training around Blaringhem, until 8 July, when it was called to take over from the 4th Division around Bois-Grenier, which also began preparations to move south. The 8th and 15th Brigades arrived on the night of 10/11 July, while the 14th moved into position on 12 July.[23]

The result of this move was that the 5th Division, the most inexperienced of the Australian divisions in France, would be the first to see major action,[24][25] doing so in the Battle of Fromelles, a week after going into the trenches. As the Germans had been reinforcing their Somme front with troops from the north, the British planned a demonstration, or feint, to try to pin these troops to the front.[26]

The attack was planned by Lieutenant-General Richard Haking, commander of the British XI Corps, [13] which adjoined II Anzac Corps to the south. The aim was to reduce the slight German salient known as the "Sugar Loaf", north-west of the German-held town of Fromelles, and was primarily intended, according to historian Chris Coulthard-Clark, "to assist the main offensive which British forces had launched along the Somme River 80 kilometres to the south on 1 July".[27]

Planning for the attack had been hasty and, as a result, the objectives were poorly defined.[28] By the time the attack was ready to be launched, its purpose as a preliminary diversion to the main action at the Somme had passed, yet Haking and his army commander, General Sir Charles Monro, were keen to go ahead.[29] Due to the pre-registration of supporting artillery, the Germans were warned about the attack.[28] Nevertheless, at 6 pm on 19 July 1916, after seven hours of preliminary bombardment, the 5th Division and British 61st Division (on the right of the Australians) attacked. The Australian 8th and 14th Brigades, attacking north of the salient, occupied the German trenches, capturing around 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), but became isolated as the 15th Brigade's effort was checked, and began taking fire to its flank from Sugar Loaf. The 15th Brigade and the British 184th Brigade had taken heavy casualties while attempting to cross no man's land, as the supporting artillery had failed to suppress the German machine guns. The 8th and 14th Brigades were forced to withdraw, through German enfilade fire, the following morning.[30] The failure was compounded when the British 61st Division asked the Australian 15th Brigade to join in a renewed attempt at 9 pm, but cancelled without informing the Australians with enough time to allow them to cancel their own attack. Consequently, half of the Australian 58th Battalion made another futile, solo effort to capture the salient, which resulted in further casualties.[31][32]

The battle resulted in the greatest loss of Australian lives in a single 24-hour period. The 5,533 Australian casualties,[28] including 400 prisoners, were equivalent to the total Australian losses in the Boer, Korean and Vietnam Wars combined.[33] The 5th Division was effectively incapacitated for many months afterwards. Two battalions, the 60th and the 32nd, each suffered more than 700 casualties, or more than 90 per cent of their fighting strength and had to be rebuilt: out of 887 personnel from the 60th Battalion, only one officer and 106 other ranks survived; the 32nd Battalion sustained 718 casualties.[34] The attack had completely failed as a diversion when its limited nature became obvious to the German defenders, while McCay's orders for the troops to push forward from the captured German trenches unnecessarily exposed them to German counter-attacks.[35] The perceived failure of the British 61st Division later impacted relations between the AIF divisions and the British.[36] Despite the heavy casualties, in its communiqués, the British GHQ described the Battle of Fromelles as "some important raids".[37]

Following the battle, the division remained in the line around Armentieres for several months.[38] As a result of its losses the 5th Division's effectiveness was greatly reduced and it was not considered "fit for offensive action for many months".[39] Despite this, according to historian Jeffrey Grey, Haking is reputed to have felt that "the attack did the division a great deal of good".[35]

Hindenburg Line, 1917

After reinforcements had arrived, the division began trench raids again in the summer of 1916.[40] In October, it deployed to the front again around Flers, leading the rest of the Australian divisions to that sector.[41][42] The division remained on the Somme during the winter.[43] In December 1916, Major General Talbot Hobbs assumed command of the 5th Division, replacing McCay who took over a depot command in England.[44][45] In the early part of 1917, the division took part in the operations on the Ancre,[46] before the Germans sought to reduce the length of their line, withdrawing to prepared positions along the Hindenburg Line.[47] Beginning on 24 February 1917, having endured a bitter winter on the Somme,[48] the division joined the pursuit, skirmishing with the German screen covering the withdrawal. On 17 March 1917, the 30th Battalion attacked towards Bapaume,[49] the objective of the previous year's Somme offensive, and found the town abandoned, a smoking ruin.[50][51] The 15th Brigade, being employed as an advanced guard (or flying column),[52] pushed south of Bapaume until, having lost touch with the British Fourth Army units on its flank, was ordered to halt. By 24 March 1917 the headlong advance had ended and a period of cautious approach to the Hindenburg defences began as the Allies began approaching the German outposts and resistance began to grow.[53] On 2 April 1917, the 14th Brigade, which had taken over the advance from the 15th, captured the villages of Doignies and Louverval, suffering 484 casualties and taking 12 prisoners in the process,[54][55] before the 5th Division was relieved by the Australian 1st Division on 6 April.[56]

When General Edmund Allenby's British Third Army launched the Battle of Arras on 9 April 1917, the Australian divisions—part of General Hubert Gough's British Fifth Army[57] since the Somme fighting—were called on to participate in an attempt to break the German flank on the Hindenburg Line at Bullecourt.[58] The 5th Division at this time was part of I Anzac under Lieutenant General William Birdwood. It avoided the first of the fighting but was thrown into the closing stages of the Second Battle of Bullecourt, having taken over from the 1st Division. The division arrived on 8 May 1917, and was tasked with holding the line to the east of Bullecourt and to consolidate the initial gains. On 12 May, the division helped advance the line on the flank of the British VII Corps, after which a strong German counterattack was repulsed on 15 May.[59][60] After the Bullecourt fighting subsided, the 5th Division was relieved by the British 20th Division, and was withdrawn from the line around 25 May and placed in corps reserve, in order so that it could rest and carry out further training. During this time, the division moved between Bancourt, Rubempre and finally to Blaringhem.[61]

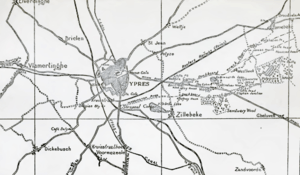

Third Battle of Ypres, 1917

The division's next major action came during the Third Battle of Ypres. On 20 September, the 5th Division took over from the 1st Division following the Battle of Menin Road,[62] which was the start of a phase of "bite-and-hold" limited-objective attacks. The next step was taken on 26 September in the Battle of Polygon Wood with two Australian divisions (4th and 5th) attacking in the centre, between V Corps on the left and attacking towards Zonnebeke, and British X Corps on their right astride the Menin Road.[63][64]

The previous day (25 September) a German counter-attack had driven in the neighbouring brigade of X Corps; however, the attack was ordered to proceed despite the Australian 15th Brigade's flank being exposed. Assigned a frontage of 1,100 yards (1,000 m), two brigades were chosen for the assault: the 14th and 15th, while the 8th assumed the role of divisional reserve.[65] On the right, attacking with an open flank, the 15th Brigade, supported by two battalions of the 8th Brigade, reached its objectives, and captured some of X Corps' objectives as well.[66] The 14th Brigade, attacking on the left, captured the Butte, in Polygon Wood.[67]

In keeping with policy, the attacking divisions were immediately relieved by the New Zealand Division and the Australian 1st, 2nd and 3rd Divisions, which attacked alongside each other during the Battle of Broodseinde as the British line edged towards Passchendaele.[68] In November 1917, the division became part of the Australian Corps, initially under Birdwood and then later under Lieutenant General John Monash.[69] The division wintered around Messines, occupying the front twice: in November – December 1917, and then again in February – March 1918.[70]

German Spring Offensive, 1918

The 5th Division, along with the 3rd and 4th Divisions, returned to action in late March as the German Spring Offensive,[71] launched on 21 March, began to threaten the vital rail hub of Amiens. Having been out of the line at the start of the offensive, the Australians were hurriedly brought south to help restore the British line in the Somme.[72] On 4 April, during the Battle of the Avre (part of the First Battle of Villers-Bretonneux), the 15th Brigade, which had been guarding crossings of the River Somme, moved to hold Hill 104 north of the town of Villers-Bretonneux, hastily filling a whole in the line that halted the German advance west of Hamel.[73] By mid-April, a renewed German push for Amiens was evident and the rest of the 5th Division, which had been held back at Vauchelles,[74] as well as the 2nd Division, was put into the line astride the Somme.[75]

On 24 April, elements of the division played a key role in the Second Battle of Villers-Bretonneux. The day before, they endured a heavy gas attack.[76] When the attack came, the 14th Brigade was holding the line around Hill 104, and the 15th Brigade was back in reserve west of the town, which was defended by the British III Corps. The German assault, for the first time spearheaded by tanks, succeeded in capturing the town and neighbouring woods from the British 8th Division. The Australian 14th Brigade mounted a strong defence in its sector, and managed to hold the high ground around Hill 104, setting the conditions for a counter-attack later that night.[77] Meanwhile, a diversionary infantry assault was put in by the Germans against the 8th Brigade's positions north of the Somme, with the 29th Battalion suffering heavy losses.[76] In response to the loss of Villers-Bretonneux, the Australian 15th Brigade, along with the 13th Brigade (from the 4th Division), were ordered to mount a counter-attack in support of III Corps. Attacking after 10 pm that night, the two brigades encircled the town, the 15th from the north and the 13th from the south, and after dawn on Anzac Day, the town itself was recaptured, with Australians and British troops advancing from three sides. This victory marked the end of the German advance towards Amiens, restoring the Allied line in the area.[78] During the battle, the 14th Brigade had also filled a supporting role,[78] securing flanking positions to the north of the town.[79]

At the end of May, the 5th Division was relieved by the 4th Division and withdrawn for a period of rest, returning to the front in the middle of June, taking up positions between Dernancourt and Sailly-Laurette.[80] During the Battle of Hamel on 4 July, the division provided one brigade – the 15th – to launch a diversionary attack around Ville-sur-Ancre, while elements of the 14th Brigade also provided support with the 55th Battalion carrying out a faint around Sailly-Laurette.[81][82] In the period leading up to the final Allied offensive, Australian divisions used Peaceful Penetration to continually harass their German opposition. Throughout June and July, numerous raids were launched, including one on the night of 29 July, around Morlancourt,[83] by troops from the 8th Brigade, which killed around 200 Germans and captured 92 prisoners, 23 machine guns, and two mortars.[84]

Hundred Days, 1918

On 8 August 1918, the Allies launched the Hundred Days offensive around Amiens, which ultimately broke the deadlock on the Western Front.[85] The Australian Corps attacked the German line between Villers-Bretonneux and Hamel, with the Canadian Corps on their right south of Villers-Bretonneux, and the British III Corps on their left north of the Somme.[86] Attacking with two brigades – the 8th and 15th – with the 14th as divisional reserve, the 5th Division followed up the initial attack of the 2nd Division, passing through their lines to take Harbonnieres, an advance of two miles, with assistance from British tanks.[87] The following day, the 5th Division, which was to have been relieved by the 1st Division, continued the advance with the 15th Brigade as the 1st Division was delayed, supporting the neighbouring advance made by the Canadian Corps towards Rosieres, while the 8th Brigade took Vauvillers.[88][89]

Withdrawn from the front on 9 August, the division rested around Villers-Bretonneux before being recommitted to the fighting.[90] In late August 1918, the 5th Division followed the German retreat to the Somme near Péronne. On 31 August, while the 2nd Division attacked Mont St Quentin, the 5th Division stood ready to exploit any opportunity to cross the Somme and take Péronne. On 1 September 1918, the 14th Brigade – the only 5th Division brigade that had been able to find a way across the Somme in late August[91] – captured the woods north and followed up by taking the main part of the town, suffering heavy casualties. The 15th Brigade, following up the 14th, assisted with mopping up, capturing the rest of the town,[92] before pushing the line towards Bretagne and St Denis.[93] By 5 September, they had reached Flamicourt and Doingt, while the 8th Brigade advanced through the woods around Bussu.[94] A British general, Henry Rawlinson, later described the Australian advances of 31 August – 4 September through Peronne and Mont St Quentin as the greatest military achievement of the war.[95]

.jpg)

By the time the Australian Corps reached the Hindenburg Line on 19 September 1918, the 5th Division was one of only two Australian divisions fit for action the other being the 3rd, [96] while the 2nd could be called upon if absolutely necessary.[97] Even in the 5th Division, though, manpower was stretched, due to heavy casualties during the earlier battles and decreased reinforcements arriving from Australia. As a result, the 15th Brigade's 60th Battalion was disbanded to keep other battalions up to strength; the 29th and 54th were also selected to disband, but this ultimately did not occur until the end of October (after the division's final battle) as the men of the 29th and 54th refused to follow the order to disband.[98][99] For the attack on the Hindenburg Line to be made on 29 September 1918, the Australian Corps was reinforced by the US 27th and 30th Divisions,[100] (both part of US II Corps). During the Battle of the St Quentin Canal, the 5th Division followed up the initial attack made by the American 30th Division. Several pockets of resistance and machine gun positions had been missed by the US troops, and these had to be overcome before the advance could continue. Once dealt with, the division captured Bellicourt and continued towards Nauroy.[101][102] After this, the division struck towards the Beaurevoir Line, capturing Joncourt, on its edge by 1 October 1918, and began sending patrols to Le Catelet.[103]

Having breached the main part of the Hindenburg Line,[102] the 5th Division was relieved by the 2nd Division.[104] On 5 October 1918, the Australian Corps was withdrawn from the line to the coast west of Amiens, handing over its line to US troops,[105][106] and the 5th Division was withdrawn to Oisemont, for a rest. The division remained out of the line until the end of the war,[107] after which its personnel were returned to Australia in drafts,[108] and its constituent units were gradually amalgamated, and then disbanded. On 29 March 1919, the staff of the 2nd and 5th Divisions combined to form 'B' Divisional Group, effectively disbanding the formation, while the individual brigades ceased exist by the end of April 1919.[109]

The division's casualties during the war amounted to 32,180 in total, of which 5,716 were killed in action, 1,875 died of wounds and 684 died from other causes, 674 were captured and 23,331 were wounded.[3] Seven members of the division received the Victoria Cross for their actions during the war: Corporal Alexander Buckley, Private Patrick Bugden, Private William Currey, Corporal Arthur Hall, Lieutenant Rupert Moon, Private John Ryan, and Major Blair Wark.[110]

Second World War

Defence of Australia, 1939–1942

Following the demobilisation of the AIF, Australia's part-time military force, the Citizens Force was reorganised in 1921 to perpetuate the numerical designations of the units of the AIF.[111] At this time four infantry divisions were raised (the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th), alongside two cavalry divisions (the 1st and 2nd). The 5th Division was not re-raised in name at this time, nor was a headquarters formed, although provisions were made to do so, with three mixed brigades being raised in Queensland (the 11th), Tasmania (the 12th), and Western Australia (the 13th), which would come under the division's command in the event of a war.[112]

In October 1939, the division was re-raised as Headquarters Northern Command. Based at Victoria Barracks, in Brisbane, the command consisted of the 7th and 11th Infantry Brigades, and the 1st Cavalry Brigade (later designated as the 1st Motor Brigade), based in Townsville and Brisbane. During the early war years, these units were mainly tasked with training to improve the readiness of the Militia, but in December 1941, they were mobilised for war service, in response to the threat of Japanese invasion. Following this, the command's units assumed a more defensive posture, with the 1st Cavalry Brigade assuming responsibility for flank defence in support of the Brisbane Covering Force, while the 7th Brigade was tasked with mounting a counter-attack in the event of an invasion aimed at Brisbane. Meanwhile, the northern Queensland-based infantry battalions remained un-brigaded, and were dispersed between Cairns, Townsville, Rockhampton and Maryborough, assuming a mobile defensive role. In January 1942, these units were formed into the 29th Brigade. As reinforcements arrived from the southern states, Northern Command was able to refocus its efforts further north: the 7th Brigade reorientated to the north of Brisbane, while the 1st Motor Brigade moved to Gympie in March.[113]

Commencing in January 1942, Northern Command headquarters was reorganised, with separate administrative and operational elements being established.[114] This process continued in April 1942, when the operational headquarters elements of Northern Command were used to re-raise the 5th Division.[115] Around this time, the division was assigned directly to the First Army.[116] By virtue of his previous role as General Officer Commanding Northern Command, Major General James Durrant was the division's first commander following its re-raising. Upon establishment it consisted of three infantry brigades: the 7th, 11th and 29th. All three were Queensland recruited. In addition, medical, engineer, supply, transport and artillery support units were allocated from Queensland-based Militia units.[117] After being established at Marist Brothers College, Ashgrove,[118] in Brisbane, several advanced parties were sent north to Aitkenvale during April and May, as the division assumed responsibility for the defence of Townsville. Under the command of Major General Edward Milford, who took over from Durrant after just a couple of weeks,[117] the division was spread across a large area including Pudilliba, Rollingstone, Castle Hill, Vantassel Creek, Woodstock, Giru, Stuart and Muntalunga, where they established a series of defensive positions and localities.[119] In July 1942, the division lost the 7th Brigade, which was sent to defend Milne Bay. The 11th Brigade assumed control of the Cairns and Cape York areas in September 1942. The divisional headquarters remained in Townsville until it moved to Dick Creek (now Upper Stony Creek).[115][120]

Assigned a defensive role in the event of a Japanese invasion, the division was given a variety of tasks including launching a counter-attack between Rollingstone and the Bohle River, as well as containing the Japanese around the Clevedon and Woodstock Hill area, opposing any landing around Bowling Green Bay, and checking an advance on Townsville. Roadblocks were also to be established between Ingham, Mount Fox, Moongobulla and Mount Spec, while counter-mobility operations were to be employed to deny a landing force access to roads around Ingham, Mount Spec and Mount Fox. The division was also tasked with beach defence at various locations, including the Bohle River – Rollingstone area, and the Haughton River – Chunda Bay area.[121]

New Guinea and New Britain, 1943–1945

In January 1943, the division was dispatched to New Guinea, to relieve the 11th Division, as a garrison force. Advanced elements consisted of the 29th Brigade and the divisional headquarters, which was established at Milne Bay initially, where it regained control of the 7th Brigade, which had seen action against the Japanese in September during the Battle of Milne Bay. The 4th Brigade arrived in March 1943, after which the 7th Brigade was sent to Port Moresby to assume a reserve role, to reinforce Wau on order.[122] During this time, the division's brigades were rotated between various positions around Milne Bay and Taupota, as well as Ferguson and Goodenough Islands. The 14th Brigade briefly came under the division's control, until it was converted into HQ Milne Bay Fortress in August 1943, as plans were made for the 5th Division to move to Port Moresby to relieve the 11th Division.[123] Meanwhile, the 11th Brigade was deployed to Merauke, forming part of Merauke Force.[117]

This plan was short-lived, and on 23 August 1943, the divisional headquarters, under Milford moved to the north coast of New Guinea, to take over the Salamaua campaign in its final stages. Landing at Nassau Bay, the headquarters took over from the 3rd Division and assumed control of its subordinate troops:[124] the Australian 15th, 17th and 29th Brigades, and the US 162nd Infantry Regiment.[123] The division occupied Salamaua on 11 September.[125] After this, the division moved to Lae, which had been captured by the 7th Division, and between September 1943 and February 1944, its headquarters assumed the designation of HQ Lae Fortress, as the area was developed as a base for further operations around the Huon Peninsula and in the Ramu Valley.[123] The division also undertook mopping up operations, securing small pockets of Japanese defenders left behind.[117] By this time, the division reported to II Corps, and had adopted the jungle divisional establishment.[126] After being re-designated once again as the 5th Division, the headquarters moved to Finschafen, assuming control of the 4th and 8th Brigades, and taking over the advance along the Rai coast towards Madang, which was secured in April 1944. Throughout the coming months, the 15th Brigade was reassigned to the division, as was the 7th Brigade, although both the 15th and 4th Brigades were returned to Australia in July and August 1944.[123]

The division's next assignment came in late 1944 and early 1945, when it was committed to the New Britain campaign, as Australian troops took over responsibility for the island from the US 40th Infantry Division. These troops had largely confined themselves to the western end of the island, while the Japanese had concentrated in the east around their strong hold at Rabaul. Throughout late 1944, the 5th Division was reorganised, and for the New Britain campaign it would consist of the 4th, 6th and 13th Brigades.[127] The Australians planned a limited campaign against the much larger Japanese force, and from October 1944 began relieving US troops. A single battalion – the 36th – deployed from Lae,[128] and landed around Cape Hoskins on the northern coast, while the following month the rest of the 6th Brigade, as well as the divisional headquarters and base sub area troops carried at a landing at Jacquinot Bay in the middle of the southern coast. A second brigade – the 13th – arrived in December, deploying from Darwin,[129] after which the Australians began a campaign to secure a defensive line across the island between Wide Bay and Open Bay, advancing along both the northern and southern coasts in an effort to restrict the Japanese to a narrow area on the Gazelle Peninsula, at the eastern end of the island. The 4th Brigade arrived in January 1945, and by February Kamandran had been reached by the 6th Brigade, followed by the Tol Plantation the following month. The 37th/52nd Battalion took over the northern coast from the 36th Battalion in April, as the 13th Brigade assumed the forward positions from the 6th, which was withdrawn back to Brisbane in June. In July, the 5th Division's headquarters was relieved by the 11th Division, which assumed control of the 4th and 13th Brigades. The 5th Division headquarters was subsequently returned to Australia.[123] In summing up its campaign on New Britain, historian Peter Dennis later wrote that the 5th Division had fought a "classic containment campaign",[130] during which it had been able to successfully contain a much larger Japanese force.[131]

The divisional headquarters was located around Mapee, Queensland, at the end of the war in August 1945. In September, rear details moved to Chermside, Queensland, where the remaining personnel were demobilised and the headquarters closed. The division was formally disbanded on 30 September 1945.[132]

Commanders

During the First World War, the following officers commanded the division:[133]

- Major General James McCay (1916)

- Major General Talbot Hobbs (1916–1919)

During the Second World War, the following officers commanded the division:[117][134]

- Major General James Durrant (1942)

- Major General Edward Milford (1942–1944)

- Major General Alan Ramsay (1944–1945)

- Major General Horace Robertson (1945)

Footnotes

- Bean 1941a, p. 42.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 3–33.

- Mallett, Ross. "First AIF Order of Battle 1914–1918: Fifth Division". University of New South Wales (Australian Defence Force Academy). Archived from the original on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- Grey 2008, p. 99.

- Palazzo 2002, p. 1.

- Grey 2008, pp. 99–100.

- Bean 1941a, pp. 41–42.

- Ellis 1920, p. 3.

- Bean 1941a, p. 64.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 21 & 38.

- Bean 1941a, p. 44.

- Cook 2014, Chapter 1.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 29.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 42–44.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 49–50.

- Ellis 1920, p. 47.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 54–55.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 55–56.

- Grey 2008, p. 105.

- Grey 2008, p. 101.

- Bean 1941a, pp. 66–67.

- "Australian Battlefields of World War I: France, 1916". Anzacs in France. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- Ellis 1920, p. 74.

- "The Western Front". Our history. Australian Army. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 54.

- Ellis 1920, p. 82.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 116.

- Grey 2008, p. 102.

- Bean 1941a, pp. 347–348.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 116–117.

- Bean 1941a, pp. 392–394.

- Ellis 1920, p. 100.

- McMullin, Ross (2006). "Disaster at Fromelles". Wartime Magazine. No. Issue 36. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- Day, Mark (14 April 2007). "Inside the mincing machine". The Australian. Archived from the original on 23 January 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- Grey 2008, p. 103.

- Sheffield 2003, p. 94.

- Ellis 1920, p. 81.

- Ellis 1920, p. 117.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 117.

- Bean 1941a, p. 447.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 270.

- Bean 1941a, p. 896.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 284.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 153–154.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 297.

- Baker, Chris. "5th Australian Division". The Long, Long Trail: The British Army in the Great War of 1914–1918. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Carlyon 2006, pp. 307–310.

- Ellis 1920, Chapter VII.

- Bean 1941b, pp. 125–126.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 311.

- Ellis 1920, p. 181.

- Bean 1941b, p. 153.

- Ellis 1920, p. 186.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 318.

- Bean 1941b, pp. 222–231.

- Ellis 1920, p. 192.

- Grey 2008, p. 104.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 125.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 129.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 205–209.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 207–217.

- Ellis 1920, p. 223.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, Map p. 131.

- Carlyon 2006, pp. 461–464.

- Ellis 1920, p. 232.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 131.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 245–248.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 474.

- Grey 2008, p. 107.

- Bean 1941c, p. 34.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 565.

- Grey 2008, p. 108.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 138.

- Ellis 1920, p. 287.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 588.

- Ellis 1920, p. 292.

- Cook 2014, Chapter 11.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 145.

- Bean 1941c, p. 578.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 308 & 311.

- Laffin 1999, pp. 87–88 & 111.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 149.

- Clissold 1982, pp. 3–12.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 311–319.

- Grey 2008, pp. 108–109.

- Carlyon 2006, Map p. 648.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 661.

- Carlyon 2006, pp. 665–667.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 337–338.

- Ellis 1920, p. 339.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 688.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 158.

- Bomford 2012, pp. 124–137.

- Bomford 2012, p. 149.

- "Mont St Quentin and Péronne". 1918: Australians in France. Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 8 April 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2007.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 163.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 708.

- Carlyon 2006, pp. 699–702.

- Ellis 1920, p. 394.

- Carlyon 2006, pp. 708–710.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 714.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 164.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 719.

- Ellis 1920, p. 380.

- Grey 2008, p. 109.

- Carlyon 2006, pp. 722 & 734.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 384–386.

- Grey 2008, pp. 120–121.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 397–399.

- Ellis 1920, pp. 405–407.

- Grey 2008, p. 125.

- Palazzo 2001, pp. 91 & 101.

- McKenzie-Smith 2018, pp. 2035–2036.

- Mellick 1998, p. 382.

- McKenzie-Smith 2018, p. 2036.

- Palazzo 2001, p. 170.

- "All-Queensland division has fine war record". Cairns Post. 29 September 1945. p. 5 – via Trove.

- Mellick 1998, p. 383.

- Mellick 1998, pp. 390–391.

- Mellick 1998, p. 393.

- Dunn, Peter. "5th Australian Division Headquarters". Oz at War. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- McKenzie-Smith 2018, pp. 2036–2037.

- McKenzie-Smith 2018, p. 2037.

- Palazzo 2001, p. 151.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 241.

- Palazzo 2001, p. 180.

- McKenzie-Smith 2018, pp. 2,036–2,037.

- Mallett 2007, p. 287.

- Long 1963, p. 251.

- Dennis et al 2008, p. 390.

- Maitland 1999, p. 112.

- "AWM52 1/5/10/81: August – September 1945: 5th Australian Division General Staff Branch". Unit war diaries, 1939–45 war. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Grey 2008, pp. 102 & 107.

- "5 Australian Infantry Division: Appointments". Orders of Battle. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

Bibliography

- Bean, Charles (1941a). The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1916. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, Volume III (12th ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 220623454.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bean, Charles (1941b). The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1917. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Volume IV (11th ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus & Robertson. OCLC 271462395.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bean, Charles (1941c). The Australian Imperial Force in France during the Main German Offensive, 1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, Volume V (8th ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 271462406.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bomford, Michelle (2012). The Battle of Mont St Quentin–Peronne 1918. Australian Army Campaigns Series # 11. Newport, New South Wales: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-1-921941962.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carlyon, Les (2006). The Great War. Sydney, New South Wales: Picador. ISBN 978-1-4050-3799-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clissold, Barry (January–March 1982). "Morlancourt: Prelude to Amiens". Sabretache. Military Historical Society of Australia. XXIII (1): 3–12. ISSN 0048-8933.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cook, Timothy (2014). Snowy to the Somme: A Muddy and Bloody Campaign, 1916–1918. Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-1-92213-263-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (1st ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-611-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dennis, Peter; et al. (2008). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551784-2.

- Ellis, A. D. (1920). The Story of the Fifth Australian Division, Being an Authoritative Account of the Division's Doings in Egypt, France and Belgium. London: Hodder and Stoughton. OCLC 464115474.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grey, Jeffrey (2008). A Military History of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69791-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laffin, John (1999). The Battle of Hamel: The Australians' Finest Victory. East Roseville, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press. ISBN 0-86417-970-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Long, Gavin (1963). The Final Campaigns. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Volume VII. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 1297619.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maitland, Gordon (1999). The Second World War and its Australian Army Battle Honours. East Roseville, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press. ISBN 0-86417-975-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mallett, Ross A. (2007). "Australian Army Logistics 1943–1945". PhD thesis. University of New South Wales. OCLC 271462761. Retrieved 29 March 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKenzie-Smith, Graham (2018). The Unit Guide: The Australian Army 1939–1945, Volume 2. Warriewood, New South Wales: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-1-925675-146.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mellick, J.S.D. (1998). "Headquarters Fifth Australian Division (AIF): Its Origins and the Defence of Townsville". Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland. 16 (9 (February)): 381–398. ISSN 1447-1345.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Palazzo, Albert (2001). The Australian Army: A History of its Organisation 1901–2001. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195515-07-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Palazzo, Albert (2002). Defenders of Australia: The 3rd Australian Division 1916–1991. Loftus, New South Wales: Australian Military Historical Publications. ISBN 1-876439-03-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheffield, Gary (2003). The Somme. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35704-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)