Conotoxin

A conotoxin is one of a group of neurotoxic peptides isolated from the venom of the marine cone snail, genus Conus.

| Alpha conotoxin precursor | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

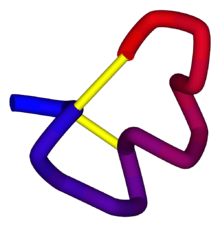

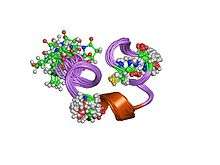

α-Conotoxin PnIB from C. pennaceus, disulfide bonds shown in yellow. From the University of Michigan's Orientations of Proteins in Membranes database, PDB: 1AKG. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Toxin_8 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF07365 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR009958 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC60004 | ||||||||

| SCOPe | 1mii / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 148 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 1akg | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Omega conotoxin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Schematic diagram of the three-dimensional structure of ω-conotoxin MVIIA (ziconotide). Disulfide bonds are shown in gold. From PDB: 1DW5. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Conotoxin | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF02950 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR004214 | ||||||||

| SCOPe | 2cco / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 112 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 1fyg | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Conotoxins, which are peptides consisting of 10 to 30 amino acid residues, typically have one or more disulfide bonds. Conotoxins have a variety of mechanisms of actions, most of which have not been determined. However, it appears that many of these peptides modulate the activity of ion channels.[1] Over the last few decades conotoxins have been the subject of pharmacological interest.[2]

Hypervariability

Conotoxins are hypervariable even within the same species. They do not act within a body where they are produced (endogenously) but act on other organisms.[4] Therefore, conotoxins genes experience less selection against mutations (like gene duplication and nonsynonymous substitution), and mutations remain in the genome longer, allowing more time for potentially beneficial novel functions to arise.[5] Variability in conotoxin components reduces the likelihood that prey organisms will develop resistance; thus cone snails are under constant selective pressure to maintain polymorphism in these genes because failing to evolve and adapt will lead to extinction (Red Queen hypothesis).[6]

Disulfide connectivities

Types of conotoxins also differ in the number and pattern of disulfide bonds.[7] The disulfide bonding network, as well as specific amino acids in inter-cysteine loops, provide the specificity of conotoxins.[8]

Types and biological activities

The number of conotoxins whose activities have been determined so far is five, and they are called the α(alpha)-, δ(delta)-, κ(kappa)-, μ(mu)-, and ω(omega)- types. Each of the five types of conotoxins attacks a different target:

- α-conotoxin inhibits nicotinic acetylcholine receptors at nerves and muscles.[9]

- δ-conotoxin inhibits fast inactivation of voltage-dependent sodium channels.[10]

- κ-conotoxin inhibits potassium channels.[11]

- μ-conotoxin inhibits voltage-dependent sodium channels in muscles.[12]

- ω-conotoxin inhibits N-type voltage-dependent calcium channels.[13] Because N-type voltage-dependent calcium channels are related to algesia (sensitivity to pain) in the nervous system, ω-conotoxin has an analgesic effect: the effect of ω-conotoxin M VII A is 100 to 1000 times that of morphine.[14] Therefore, a synthetic version of ω-conotoxin M VII A has found application as an analgesic drug ziconotide (Prialt).[15]

Alpha

Alpha conotoxins have two types of cysteine arrangements,[16] and are competitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonists.

Delta, kappa, and omega

Omega, delta and kappa families of conotoxins have a knottin or inhibitor cystine knot scaffold. The knottin scaffold is a very special disulfide-through-disulfide knot, in which the III-VI disulfide bond crosses the macrocycle formed by two other disulfide bonds (I-IV and II-V) and the interconnecting backbone segments, where I-VI indicates the six cysteine residues starting from the N-terminus. The cysteine arrangements are the same for omega, delta and kappa families, even though omega conotoxins are calcium channel blockers, whereas delta conotoxins delay the inactivation of sodium channels, and kappa conotoxins are potassium channel blockers.[7]

Mu

| Mu-conotoxin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

nmr solution structure of piiia toxin, nmr, 20 structures | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Mu-conotoxin | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF05374 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0083 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR008036 | ||||||||

| SCOPe | 1gib / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 112 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 1ag7 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Mu-conotoxins have two types of cysteine arrangements, but the knottin scaffold is not observed.[17] Mu-conotoxins target the muscle-specific voltage-gated sodium channels,[7] and are useful probes for investigating voltage-dependent sodium channels of excitable tissues.[17][18] Mu-conotoxins target the voltage-gated sodium channels, preferentially those of skeletal muscle,[19] and are useful probes for investigating voltage-dependent sodium channels of excitable tissues.[20]

Different subtypes of voltage-gated sodium channels are found in different tissues in mammals, e.g., in muscle and brain, and studies have been carried out to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the mu-conotoxins for the different isoforms.[21]

See also

- Contryphan, members of "conotoxin O2"

- Conantokins, also known as "conotoxin B"

References

- Terlau H, Olivera BM (2004). "Conus venoms: a rich source of novel ion channel-targeted peptides". Physiol. Rev. 84 (1): 41–68. doi:10.1152/physrev.00020.2003. PMID 14715910.

- Olivera BM, Teichert RW (2007). "Diversity of the neurotoxic Conus peptides: a model for concerted pharmacological discovery". Mol Interv. 7 (5): 251–60. doi:10.1124/mi.7.5.7. PMID 17932414.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-29. Retrieved 2017-03-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Olivera BM, Watkins M, Bandyopadhyay P, Imperial JS, de la Cotera EP, Aguilar MB, Vera EL, Concepcion GP, Lluisma A (September 2012). "Adaptive radiation of venomous marine snail lineages and the accelerated evolution of venom peptide genes". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1267 (1): 61–70. Bibcode:2012NYASA1267...61O. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06603.x. PMC 3488454. PMID 22954218.

- Wong ES, Belov K (March 2012). "Venom evolution through gene duplications". Gene. 496 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.009. PMID 22285376.

- Liow LH, Van Valen L, Stenseth NC (July 2011). "Red Queen: from populations to taxa and communities". Trends Ecol. Evol. 26 (7): 349–58. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2011.03.016. PMID 21511358.

- Jones RM, McIntosh JM (2001). "Cone venom--from accidental stings to deliberate injection". Toxicon. 39 (10): 1447–1451. doi:10.1016/S0041-0101(01)00145-3. PMID 11478951.

- Sato K, Kini RM, Gopalakrishnakone P, Balaji RA, Ohtake A, Seow KT, Bay BH (2000). "lambda-conotoxins, a new family of conotoxins with unique disulfide pattern and protein folding. Isolation and characterization from the venom of Conus marmoreus". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (50): 39516–39522. doi:10.1074/jbc.M006354200. PMID 10988292.

- Nicke A, Wonnacott S, Lewis RJ (2004). "Alpha-conotoxins as tools for the elucidation of structure and function of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes". Eur. J. Biochem. 271 (12): 2305–2319. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04145.x. PMID 15182346.

- Leipold E, Hansel A, Olivera BM, Terlau H, Heinemann SH (2005). "Molecular interaction of delta-conotoxins with voltage-gated sodium channels". FEBS Lett. 579 (18): 3881–3884. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2005.05.077. PMID 15990094.

- Shon KJ, Stocker M, Terlau H, Stühmer W, Jacobsen R, Walker C, Grilley M, Watkins M, Hillyard DR, Gray WR, Olivera BM (1998). "kappa-Conotoxin PVIIA is a peptide inhibiting the shaker K+ channel". J. Biol. Chem. 273 (1): 33–38. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.1.33. PMID 9417043.

- Li RA, Tomaselli GF (2004). "Using the deadly mu-conotoxins as probes of voltage-gated sodium channels". Toxicon. 44 (2): 117–122. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.03.028. PMC 2698010. PMID 15246758.

- Nielsen KJ, Schroeder T, Lewis R (2000). "Structure-activity relationships of omega-conotoxins at N-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels". J. Mol. Recognit. 13 (2): 55–70. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1352(200003/04)13:2<55::AID-JMR488>3.0.CO;2-O. PMID 10822250. Archived from the original (abstract) on 2011-08-13.

- Bowersox SS, Luther R (1998). "Pharmacotherapeutic potential of omega-conotoxin MVIIA (SNX-111), an N-type neuronal calcium channel blocker found in the venom of Conus magus". Toxicon. 36 (11): 1651–1658. doi:10.1016/S0041-0101(98)00158-5. PMID 9792182.

- Prommer E (2006). "Ziconotide: a new option for refractory pain". Drugs Today. 42 (6): 369–78. doi:10.1358/dot.2006.42.6.973534. PMID 16845440.

- Gray WR, Olivera BM, Zafaralla GC, Ramilo CA, Yoshikami D, Nadasdi L, Hammerland LG, Kristipati R, Ramachandran J, Miljanich G (1992). "Novel alpha- and omega-conotoxins from Conus striatus venom". Biochemistry. 31 (41): 11864–11873. doi:10.1021/bi00162a027. PMID 1390774.

- Nielsen KJ, Watson M, Adams DJ, Hammarström AK, Gage PW, Hill JM, Craik DJ, Thomas L, Adams D, Alewood PF, Lewis RJ (July 2002). "Solution structure of mu-conotoxin PIIIA, a preferential inhibitor of persistent tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 277 (30): 27247–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.M201611200. PMID 12006587.

- Zeikus RD, Gray WR, Cruz LJ, Olivera BM, Kerr L, Moczydlowski E, Yoshikami D (1985). "Conus geographus toxins that discriminate between neuronal and muscle sodium channels". J. Biol. Chem. 260 (16): 9280–8. PMID 2410412.

- McIntosh JM, Jones RM (October 2001). "Cone venom--from accidental stings to deliberate injection". Toxicon. 39 (10): 1447–51. doi:10.1016/S0041-0101(01)00145-3. PMID 11478951.

- Cruz LJ, Gray WR, Olivera BM, Zeikus RD, Kerr L, Yoshikami D, Moczydlowski E (August 1985). "Conus geographus toxins that discriminate between neuronal and muscle sodium channels". J. Biol. Chem. 260 (16): 9280–8. PMID 2410412.

- Floresca CZ (2003). "A comparison of the mu-conotoxins by [3H]saxitoxin binding assays in neuronal and skeletal muscle sodium channel". Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 190 (2): 95–101. doi:10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00153-4. PMID 12878039.

External links

- Conotoxins at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Baldomero "Toto" Olivera's Short Talk. "Conus Peptides".

- Kaas Q, Westermann JC, Halai R, Wang CK, Craik DJ. "ConoServer". Institute of Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland, Australia. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

A database for conopeptide sequences and structures