Zaparoan languages

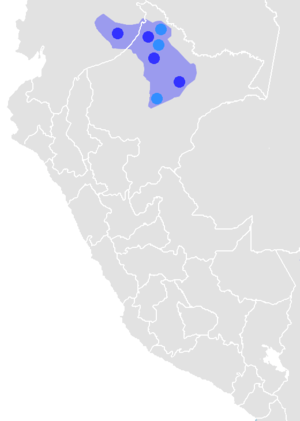

Zaparoan (also Sáparoan, Záparo, Zaparoano, Zaparoana) is an endangered language family of Peru and Ecuador with fewer than 100 speakers. Zaparoan speakers seem to have been very numerous before the arrival of the Europeans. However, their groups have been decimated by imported diseases and warfare, and only a handful of them have survived.

| Zaparoan | |

|---|---|

| Saparoan | |

| Geographic distribution | western Amazon |

| Linguistic classification | Saparo–Yawan ?

|

| Glottolog | zapa1251[1] |

| |

Languages

There were 39 Zaparoan-speaking tribes at the beginning of the 20th century,[2] every one of them presumably using its own distinctive language or dialect. Most of them have become extinct before being recorded, however, and we have information only about nine of them.

- Zaparo group

- Iquito–Cahuarano

- Unclassified

Aushiri and Omurano are included by Stark (1985). Aushiri is generally accepted as Zaparoan, but Omurano remains unclassified in other descriptions.

Mason (1950)

Internal classification of the Zaparoan languages by Mason (1950):[3]

- Coronado group

- Coronado (Ipapiza, Hichachapa, Kilinina)

- Tarokeo

- Chudavina (?)

- Miscuara (?)

- Oa (Oaki, Deguaca, Santa Rosina)

- Andoa group

- Andoa

- Guallpayo

- Guasaga

- Murato

- Gae (Siaviri)

- Semigae

- Aracohor

- Mocosiohor

- Usicohor

- Ichocomohor

- Itoromohor

- Maithiore

- Comacor (?)

- Iquito (Amacacora, Kiturran, Puca-Uma)

- Iquito

- Maracana (Cawarano ?)

- Auve

- Asaruntoa (?)

- Záparo group

- Muegano

- Curaray

- Matagen

- Yasuni

- Manta

- Nushino

- Rotuno

- Supinu

Genetic relations

The relationship of zaparoan languages with other language families of the area is uncertain. It is generally considered isolated. Links with other languages or families have been proposed but none has been widely accepted so far.

- Payne (1984) and Kaufman (1994) suggest a relationship with the Yaguan family in a Sáparo–Yáwan stock, contrary to Greenberg's (1987) classification.

- Swadesh (1954) also groups Zaparoan with Yaguan within his Zaparo–Peba phylum.

- Greenberg (1987) places Zaparoan together with the Cahuapanan family into a Kahuapana–Zaparo grouping within his larger Andean phylum, but this is generally rejected by historical linguists.

- Kaufman (1994) notes that Tovar (1984) includes the unclassified Taushiro under Zaparoan following the tentative opinion of SSILA.

- Stark (1985) includes the extinct Omurano under Zaparoan. Gordon (2005) follows Stark.

- Mason (1950: 236–238) groups Bora–Witoto, Tupian, and Zaparoan together as part of a proposed Macro-Tupí-Guaranían family.[3]

Language contact

Jolkesky (2016) notes that there are lexical similarities with the Omurano, Arawakan, Quechuan, and Peba-Yagua language families due to contact.[4]

Family features

Pronouns

Zaparoan languages distinguishes between inclusive and exclusive we and consider the first person singular as the default person. A rare feature is the existence of two sets of personal pronouns with different syntactic values according to the nature of the sentence. Active pronouns are subject in independent clauses and object in dependent ones, while passive pronouns are subject in independent clauses and passive in dependent ones :

Thus

- (arabella) Cuno maaji cua masuu-nuju-quiaa na mashaca cua ratu-nu-ra. (this woman is always inviting me to drink masato [5] where cua is object in the main clause and subject in the subordinate one.

- (zaparo) /tʃa na itʌkwaha/ (you wil fall) cp /tajkwa ko pani tʃa tʃata ikwano/ (I don't want to go with you) [6]

| Personal pronouns in Zaparoan languages | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1S | 2S | 3S | 1Pin | 1Pex | 2P | 3AP | |

| Zaparo | ko / kwi / k- | tʃa / tʃ- / k-/ ki | naw / no / n-ˑ | pa /p- | kana /kaʔno | kina / kiʔno | na |

| Arabela | janiya / -nijia / cua cuo- / cu- / qui | quiajaniya / quiaa / quia / quio- -quia / cero | nojuaja / na / ne- / no- -Vri / -quinio | pajaniya / paa / pa / po- pue- / -pue | canaa | niajaniya / niaa / nia / nio- | nojori / na / no- |

| Iquito | cu / quí / quíija | quia / quiáaja | anúu / anúuja | p'++ja | cana / canáaja | naá / nahuaáca | |

| Conambo | kwiɣia / ku | kyaχa | |||||

Numerals

| Gloss | Zaparoan languages | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zaparo | Andoa | Arabela | Iquito | |

| 1 | nuquaqui | nikínjo | niquiriyatu | núquiica |

| 2 | namisciniqui | ishki | caapiqui | cuúmi |

| 3 | haimuckumarachi | kímsa | jiuujianaraca | s++saramaj+táami |

| 4 | ckaramaitacka | |||

Vocabulary

Loukotka (1968) lists the following basic vocabulary items for Zaparoan language varieties.[7]

| gloss | Záparo | Conambo | Andoa | Simigae | Chiripuno | Iquito | Cahuarano |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| one | nokoáki | nukaki | nikíño | nóki | núki | ||

| two | namesániki | tarkaningu | ishki | koːmi | kómu | ||

| head | ku-anák | ku-anaka | pan-aka | p-anák | p-anák | pá-nak | |

| eye | nu-námits | ku-iyamixa | pa-namix | henizy | namixía | puí-nami | poí-nami |

| woman | itumu | maxi | maxi | mãxi | muesaxí | itémo | |

| fire | unámisok | umáni | ománi | omani | inámi | inámi | |

| sun | yánuk | yañakwa | apánamu | poánámu | pananú | núnami | nianamí |

| star | narika | narexa | arixya | arishya | narexa | narexa | |

| maize | sáuk | tasáuku | dzáuku | sakoó | shakárok | shekárok | |

| house | itü | ité | ki-t'a | dahápu | íta | íta | |

| white | ushíksh | ushikya | ishi-sinwa | makúshini | mosotín | musiténa |

Proto-language

| Proto-Zaparoan | |

|---|---|

| Proto-Záparoan | |

| Reconstruction of | Zaparoan languages |

Proto-Záparoan reconstructions by de Carvalho (2013):[8]

gloss Proto-Záparoan ‘bee, wasp’ *ahapaka ‘stick’ *amaka ‘to kill’ *amo ‘woman's sibling’ *ana- ‘cloud, smoke’ *anahaka ‘head’ *anaka ‘pain’ *anaw ‘to come’ *ani- ‘to cut down’ *anu- ‘to talk’ *ati- ‘to eat’ *atsa- ‘tooth’ *ika- ‘to go’ *ikwa- ‘foot’ *ino- ‘benefactive’ *-iɾa ‘fat, large (for fruits)’ *iɾisi ‘house’ *ita ‘urine’ *isa- ‘negative nominalization’ *-jaw ‘number suffix’ *-ka ‘hair; feather’ *kaha- ‘1st person, excl. plural’ *kana ‘to cut (hair)’ *kə- ‘raw’ *maha ‘to cook’ *mahi ‘to sleep’ *makə- ‘guts’ *mara ‘to tie’ *maraw- ‘to escape, to flee’ *masi- ‘to do’ *mi- ‘rotten’ *moka ‘3rd person plural’ *na- ‘hill’ *naku- ‘blood’ *nana-ka ‘3rd person singular’ *naw- ‘masculine, singular’ *-nu ‘infinitive’ *-nu ‘to want/like; love’ *pani- ‘fish; stingray?’ *sapi ‘to taste (food)’ *sani- ‘lice’ *sukana ‘bad’ *səsa ‘to lick’ *tamə- ‘foreigner, stranger; to hate?’ *tawə- ‘to listen’ *tawhi- ‘feminine, singular’ *-tu ‘causative suffix’ *-tə ‘where’ *tə- ‘to rest; to be new’ *tsami- ‘rain’ *umaru

Bibliography

- Adelaar, Willem F. H.; & Muysken, Pieter C. (2004). The languages of the Andes. Cambridge language surveys. Cambridge University Press.

- Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (1987). Language in the Americas. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Kaufman, Terrence. (1990). Language history in South America: What we know and how to know more. In D. L. Payne (Ed.), Amazonian linguistics: Studies in lowland South American languages (pp. 13–67). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70414-3.

- Kaufman, Terrence. (1994). The native languages of South America. In C. Mosley & R. E. Asher (Eds.), Atlas of the world's languages (pp. 46–76). London: Routledge.

- Payne, Doris. (1984). Evidence for a Yaguan-Zaparoan connection. In D. Derbyshire (Ed.), SIL working papers: University of North Dakota session (Vol. 28; pp. 131–156).

- Stark, Louisa R. (1985). Indigenous languages of lowland Ecuador: History and current status. In H. E. M. Klein & L. R. Stark (Eds.), South American Indian languages: Retrospect and prospect (pp. 157–193). Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Suárez, Jorge. (1974). South American Indian languages. In Encyclopædia Britannica (15th ed., Vol. 17, pp. 105–112).

- Swadesh, Morris. (1959). Mapas de clasificación lingüística de México y las Américas. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Tovar, Antonio; & Larrucea de Tovar, Consuelo. (1984). Catálogo de las lenguas de América de Sur (nueva edición). Madrid: Gredos.

Notes

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Zaparoan". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- La famille linguistique Zaparo, H. Beuchat and P. Rivet – Journal de la société des américanistes – Année 1908 lien Volume 5 pp. 235–249

- Mason, John Alden (1950). "The languages of South America". In Steward, Julian (ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. 6. Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 143. pp. 157–317.

- Jolkesky, Marcelo Pinho de Valhery (2016). Estudo arqueo-ecolinguístico das terras tropicais sul-americanas (Ph.D. dissertation) (2 ed.). Brasília: University of Brasília.

- Dicconario Arabella—Castellano, Rolland G. Rich, Instituto Lingüistico de Verano, Perú – 1999

- Bosquejo Gramatical del Zaparo, M. Catherine Peeke, Cuadernos Etnolingüisticos, n°14, Instituto Lingüistico de Verano, Quito, 1991

- Loukotka, Čestmír (1968). Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center.

- de Carvalho, F. O. (2013). On Záparoan as a valid genetic unity: Preliminary correspondences and the status of Omurano. In Revista Brasileira de Linguística Antropológica. Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 91-116. Accessed from DiACL, 9 February 2020.

External links

| Wiktionary has a list of reconstructed forms at Appendix:Proto-Zaparoan reconstructions |