Lidocaine

Lidocaine, also known as lignocaine, is a medication used to numb tissue in a specific area (local anesthetic).[4] It is also used to treat ventricular tachycardia and to perform nerve blocks.[3][4] Lidocaine mixed with a small amount of adrenaline (epinephrine) is available to allow larger doses for numbing, to decrease bleeding, and to make the numbing effect last longer.[4] When used as an injectable, lidocaine typically begins working within four minutes and lasts for half an hour to three hours.[4][5] Lidocaine mixtures may also be applied directly to the skin or mucous membranes to numb the area.[4]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | Lidocaine /ˈlaɪdəˌkeɪn/[1][2] lignocaine /ˈlɪɡnəˌkeɪn/ |

| Trade names | Xylocaine, others |

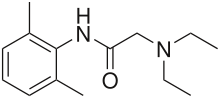

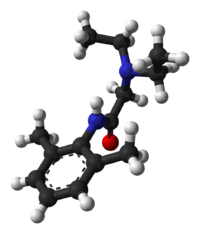

| Other names | N-(2,6-dimethylphenyl)-N2,N2-diethylglycinamide |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Local Monograph Injectable Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682701 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | intravenous, subcutaneous, topical, by mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 35% (by mouth) 3% (topical) |

| Metabolism | Liver,[3] 90% CYP3A4-mediated |

| Onset of action | within 1.5 min (IV)[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5 h to 2 h |

| Duration of action | 10 min to 20 min(IV),[3] 0.5 h to 3 h (local)[4][5] |

| Excretion | Kidney[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.821 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H22N2O |

| Molar mass | 234.343 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 68 °C (154 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects with intravenous use include sleepiness, muscle twitching, confusion, changes in vision, numbness, tingling, and vomiting.[3] It can cause low blood pressure and an irregular heart rate.[3] There are concerns that injecting it into a joint can cause problems with the cartilage.[4] It appears to be generally safe for use in pregnancy.[3] A lower dose may be required in those with liver problems.[3] It is generally safe to use in those allergic to tetracaine or benzocaine.[4] Lidocaine is an antiarrhythmic medication of the class Ib type.[3] This means it works by blocking sodium channels and thus decreasing the rate of contractions of the heart.[3] When it is used locally as a numbing agent, local neurons cannot signal the brain.[4]

Lidocaine was discovered in 1946 and went on sale in 1948.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] It is available as a generic medication.[4][8] It is sold under a number of brand names including Xylocaine.[4] In 2017, it was the 208th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[9][10]

Medical uses

Local numbing agent

The efficacy profile of lidocaine as a local anaesthetic is characterized by a rapid onset of action and intermediate duration of efficacy. Therefore, lidocaine is suitable for infiltration, block, and surface anaesthesia. Longer-acting substances such as bupivacaine are sometimes given preference for spinal and epidural anaesthesias; lidocaine, though, has the advantage of a rapid onset of action. Adrenaline vasoconstricts arteries, reducing bleeding and also delaying the resorption of lidocaine, almost doubling the duration of anaesthesia.

Lidocaine is one of the most commonly used local anaesthetics in dentistry. It can be administered in multiple ways, most often as a nerve block or infiltration, depending on the type of treatment carried out and the area of the mouth worked on.[11]

For surface anaesthesia, several formulations can be used for endoscopies, before intubations, etc. Buffering the pH of lidocaine makes local numbing less painful.[12] Lidocaine drops can be used on the eyes for short ophthalmic procedures. There is tentative evidence for topical lidocaine for neuropathic pain and skin graft donor site pain.[13][14] As a local numbing agent, it is used for the treatment of premature ejaculation.[15]

An adhesive transdermal patch containing a 5% concentration of lidocaine in a hydrogel bandage, is approved by the US FDA for reducing nerve pain caused by shingles.[16] The transdermal patch is also used for pain from other causes, such as compressed nerves and persistent nerve pain after some surgeries.

Heart arrhythmia

Lidocaine is also the most important class-1b antiarrhythmic drug; it is used intravenously for the treatment of ventricular arrhythmias (for acute myocardial infarction, digoxin poisoning, cardioversion, or cardiac catheterization) if amiodarone is not available or contraindicated. Lidocaine should be given for this indication after defibrillation, CPR, and vasopressors have been initiated. A routine preventative dose is no longer recommended after a myocardial infarction as the overall benefit is not convincing.[17]

Epilepsy

A 2013 review on treatment for neonatal seizures recommended intravenous lidocaine as a second-line treatment, if phenobarbital fails to stop seizures.[18]

Other

Intravenous lidocaine infusions are also used to treat chronic pain and acute surgical pain as an opiate sparing technique. The quality of evidence for this use is poor so it is difficult to compare it to placebo or an epidural.[19]

Inhaled lidocaine can be used as a cough suppressor acting peripherally to reduce the cough reflex. This application can be implemented as a safety and comfort measure for patients who have to be intubated, as it reduces the incidence of coughing and any tracheal damage it might cause when emerging from anaesthesia.[20]

Lidocaine, along with ethanol, ammonia, and acetic acid, may also help in treating jellyfish stings, both numbing the affected area and preventing further nematocyst discharge.[21][22]

For gastritis, drinking a viscous lidocaine formulation may help with the pain.[23]

Adverse effects

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are rare when lidocaine is used as a local anesthetic and is administered correctly. Most ADRs associated with lidocaine for anesthesia relate to administration technique (resulting in systemic exposure) or pharmacological effects of anesthesia, and allergic reactions only rarely occur.[24] Systemic exposure to excessive quantities of lidocaine mainly result in central nervous system (CNS) and cardiovascular effects – CNS effects usually occur at lower blood plasma concentrations and additional cardiovascular effects present at higher concentrations, though cardiovascular collapse may also occur with low concentrations. ADRs by system are:

- CNS excitation: nervousness, agitation, anxiety, apprehension, tingling around the mouth (circumoral paraesthesia), headache, hyperesthesia, tremor, dizziness, pupillary changes, psychosis, euphoria, hallucinations, and seizures

- CNS depression with increasingly heavier exposure: drowsiness, lethargy, slurred speech, hypoesthesia, confusion, disorientation, loss of consciousness, respiratory depression and apnoea.

- Cardiovascular: hypotension, bradycardia, arrhythmias, flushing, venous insufficiency, increased defibrillator threshold, edema, and/or cardiac arrest – some of which may be due to hypoxemia secondary to respiratory depression.[25]

- Respiratory: bronchospasm, dyspnea, respiratory depression or arrest

- Gastrointestinal: metallic taste, nausea, vomiting

- Ears: tinnitus

- Eyes: local burning, conjunctival hyperemia, corneal epithelial changes/ulceration, diplopia, visual changes (opacification)

- Skin: itching, depigmentation, rash, urticaria, edema, angioedema, bruising, inflammation of the vein at the injection site, irritation of the skin when applied topically

- Blood: methemoglobinemia

- Allergy

ADRs associated with the use of intravenous lidocaine are similar to toxic effects from systemic exposure above. These are dose-related and more frequent at high infusion rates (≥3 mg/min). Common ADRs include: headache, dizziness, drowsiness, confusion, visual disturbances, tinnitus, tremor, and/or paraesthesia. Infrequent ADRs associated with the use of lidocaine include: hypotension, bradycardia, arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, muscle twitching, seizures, coma, and/or respiratory depression.[25]

It is generally safe to use lidocaine with vasoconstrictor such as adrenaline, including in regions such as the nose, ears, fingers, and toes.[26] While concerns of tissue death if used in these areas have been raised, evidence does not support these concerns.[26]

Interactions

Any drugs that are also ligands of CYP3A4 and CYP1A2 can potentially increase serum levels and potential for toxicity or decrease serum levels and the efficacy, depending on whether they induce or inhibit the enzymes, respectively. Drugs that may increase the chance of methemoglobinemia should also be considered carefully. Dronedarone and liposomal morphine are both absolutely a contraindication, as they may increase the serum levels, but hundreds of other drugs require monitoring for interaction.[27]

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications for the use of lidocaine include:

- Heart block, second or third degree (without pacemaker)

- Severe sinoatrial block (without pacemaker)

- Serious adverse drug reaction to lidocaine or amide local anesthetics

- Hypersensitivity to corn and corn-related products (corn-derived dextrose is used in the mixed injections)

- Concurrent treatment with quinidine, flecainide, disopyramide, procainamide (class I antiarrhythmic agents)

- Prior use of amiodarone hydrochloride

- Adams-Stokes syndrome[28]

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome[28]

- Lidocaine viscous is not recommended by the FDA to treat teething pain in children and infants.[29]

Exercise caution in patients with any of these:

- Hypotension not due to arrhythmia

- Bradycardia

- Accelerated idioventricular rhythm

- Elderly patients

- Pseudocholinesterase deficiency

- Intra-articular infusion (this is not an approved indication and can cause chondrolysis)

- Porphyria, especially acute intermittent porphyria; lidocaine has been classified as porphyrogenic because of the hepatic enzymes it induces,[30] although clinical evidence suggests it is not.[31] Bupivacaine is a safe alternative in this case.

- Impaired liver function – people with lowered hepatic function may have an adverse reaction with repeated administration of lidocaine because the drug is metabolized by the liver. Adverse reactions may include neurological symptoms (e.g. dizziness, nausea, muscle twitches, vomiting, or seizures).[32]

Overdosage

Overdoses of lidocaine may result from excessive administration by topical or parenteral routes, accidental oral ingestion of topical preparations by children (who are more susceptible to overdose), accidental intravenous (rather than subcutaneous, intrathecal, or paracervical) injection, or from prolonged use of subcutaneous infiltration anesthesia during cosmetic surgery.

Such overdoses have often led to severe toxicity or death in both children and adults. Lidocaine and its two major metabolites may be quantified in blood, plasma, or serum to confirm the diagnosis in potential poisoning victims or to assist forensic investigation in a case of fatal overdose.

Lidocaine is often given intravenously as an antiarrhythmic agent in critical cardiac-care situations.[33] Treatment with intravenous lipid emulsions (used for parenteral feeding) to reverse the effects of local anaesthetic toxicity is becoming more common.[34]

Postarthroscopic glenohumeral chondrolysis

Lidocaine in large amounts may be toxic to cartilage and intra-articular infusions can lead to postarthroscopic glenohumeral chondrolysis.[35]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Lidocaine alters signal conduction in neurons by prolonging the inactivation of the fast voltage-gated Na+ channels in the neuronal cell membrane responsible for action potential propagation.[36] With sufficient blockage, the voltage-gated sodium channels will not open and an action potential will not be generated. Careful titration allows for a high degree of selectivity in the blockage of sensory neurons, whereas higher concentrations also affect other types of neurons.

The same principle applies for this drug's actions in the heart. Blocking sodium channels in the conduction system, as well as the muscle cells of the heart, raises the depolarization threshold, making the heart less likely to initiate or conduct early action potentials that may cause an arrhythmia.[37]

Pharmacokinetics

When used as an injectable it typically begins working within four minutes and lasts for half an hour to three hours.[4][5] Lidocaine is about 95% metabolized (dealkylated) in the liver mainly by CYP3A4 to the pharmacologically active metabolites monoethylglycinexylidide (MEGX) and then subsequently to the inactive glycine xylidide. MEGX has a longer half-life than lidocaine, but also is a less potent sodium channel blocker.[38] The volume of distribution is 1.1 L/kg to 2.1 L/kg, but congestive heart failure can decrease it. About 60% to 80% circulates bound to the protein alpha1 acid glycoprotein. The oral bioavailability is 35% and the topical bioavailability is 3%.

The elimination half-life of lidocaine is biphasic and around 90 min to 120 min in most patients. This may be prolonged in patients with hepatic impairment (average 343 min) or congestive heart failure (average 136 min).[39] Lidocaine is excreted in the urine (90% as metabolites and 10% as unchanged drug).[40]

History

Lidocaine, the first amino amide–type local anesthetic, was first synthesized under the name 'xylocaine' by Swedish chemist Nils Löfgren in 1943.[41][42][43] His colleague Bengt Lundqvist performed the first injection anesthesia experiments on himself.[41] It was first marketed in 1949.

Society and culture

Dosage forms

Lidocaine, usually in the form of its hydrochloride salt, is available in various forms including many topical formulations and solutions for injection or infusion.[44] It is also available as a transdermal patch, which is applied directly to the skin.

- Lidocaine hydrochloride 2% epinephrine 1:80,000 solution for injection in a cartridge

Lidocaine hydrochloride 1% solution for injection

Lidocaine hydrochloride 1% solution for injection Topical lidocaine spray

Topical lidocaine spray 2% viscous lidocaine

2% viscous lidocaine

Cost

The wholesale cost in the developing world in 2014 was US$0.45 to $1.05 wholesale per 20 ml vial of medication.[45]

Names

Lidocaine is the International Nonproprietary Name (INN), British Approved Name (BAN), and Australian Approved Name (AAN),[46] while lignocaine is the former BAN and AAN. Both the old and new names will be displayed on the product label in Australia until at least 2023.[47]

Xylocaine is a brand name.

Recreational use

Lidocaine is not currently listed by the World Anti-Doping Agency as an illegal substance.[48] It is used as an adjuvant, adulterant, and diluent to street drugs such as cocaine and heroin.[49] It is one of the three common ingredients in site enhancement oil used by bodybuilders.[50]

Adulterant in cocaine

Lidocaine is often added to cocaine as a diluent.[51][52] Cocaine and lidocaine both numb the gums when applied. This gives the user the impression of high-quality cocaine, when in actuality the user is receiving a diluted product.[53]

Compendial status

Veterinary use

It is a component of the veterinary drug Tributame along with embutramide and chloroquine used to carry out euthanasia on horses and dogs.[55][56]

See also

- Dimethocaine (has some DRI activity)

- Lidocaine/prilocaine

- Procaine

- Mexiletine

References

- "Lidocaine". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- "Lidocaine". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- "Lidocaine Hydrochloride (Antiarrhythmic)". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-08-10. Retrieved Aug 26, 2015.

- "Lidocaine Hydrochloride (Local)". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved Aug 26, 2015.

- J. P. Nolan; P. J. F. Baskett (1997). "Analgesia and anaesthesia". In David Skinner; Andrew Swain; Rodney Peyton; Colin Robertson (eds.). Cambridge Textbook of Accident and Emergency Medicine. Project co-ordinator, Fiona Whinster. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 194. ISBN 9780521433792. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Scriabine, Alexander (1999). "Discovery and development of major drugs currently in use". In Ralph Landau; Basil Achilladelis; Alexander Scriabine (eds.). Pharmaceutical Innovation: Revolutionizing Human Health. Philadelphia: Chemical Heritage Press. p. 211. ISBN 9780941901215. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 22. ISBN 9781284057560.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Lidocaine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Local anaesthetic drugs".

- Cepeda MS, Tzortzopoulou A, Thackrey M, Hudcova J, Arora Gandhi P, Schumann R (December 2010). Tzortzopoulou A (ed.). "Adjusting the pH of lidocaine for reducing pain on injection". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD006581. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006581.pub2. PMID 21154371. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006581.pub3. If this is an intentional citation to a retracted paper, please replace

{{Retracted}}with{{Retracted|intentional=yes}}.) - Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA, Quinlan J (July 2014). Derry S (ed.). "Topical lidocaine for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD010958. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010958.pub2. PMC 6540846. PMID 25058164.

- Sinha S, Schreiner AJ, Biernaskie J, Nickerson D, Gabriel VA (November 2017). "Treating pain on skin graft donor sites: Review and clinical recommendations". The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 83 (5): 954–964. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001615. PMID 28598907.

- "Lidocaine/prilocaine spray for premature ejaculation". Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. 55 (4): 45–48. April 2017. doi:10.1136/dtb.2017.4.0469. PMID 28408390.

- Kumar M, Chawla R, Goyal M (2015). "Topical anesthesia". Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology. 31 (4): 450–6. doi:10.4103/0970-9185.169049. PMC 4676230. PMID 26702198.

- Martí-Carvajal AJ, Simancas-Racines D, Anand V, Bangdiwala S (August 2015). "Prophylactic lidocaine for myocardial infarction". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD008553. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008553.pub2. PMID 26295202.

- Slaughter LA, Patel AD, Slaughter JL (March 2013). "Pharmacological treatment of neonatal seizures: a systematic review". Journal of Child Neurology. 28 (3): 351–64. doi:10.1177/0883073812470734. PMC 3805825. PMID 23318696.

- Weibel S, Jelting Y, Pace NL, Helf A, Eberhart LH, Hahnenkamp K, et al. (June 2018). "Continuous intravenous perioperative lidocaine infusion for postoperative pain and recovery in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD009642. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009642.pub3. PMC 6513586. PMID 29864216.

- Biller JA (2007). "Airway obstruction, bronchospasm, and cough". In Berger AM, Shuster JL, Von Roenn JH (eds.). Principles and practice of palliative care and supportive oncology. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 297–307. ISBN 978-0-7817-9595-1.

Inhaled lidocaine is used to suppress cough during bronchoscopy. Animal studies and a few human studies suggest that lidocaine has an antitussive effect…

- Birsa LM, Verity PG, Lee RF (May 2010). "Evaluation of the effects of various chemicals on discharge of and pain caused by jellyfish nematocysts". Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 151 (4): 426–30. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2010.01.007. PMID 20116454.

- Morabito R, Marino A, Dossena S, La Spada G (Jun 2014). "Nematocyst discharge in Pelagia noctiluca (Cnidaria, Scyphozoa) oral arms can be affected by lidocaine, ethanol, ammonia and acetic acid". Toxicon. 83: 52–8. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.03.002. PMID 24637105.

- James G. Adams (2012). "32". Emergency Medicine: Clinical Essentials. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455733941. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Jackson D, Chen AH, Bennett CR (October 1994). "Identifying true lidocaine allergy". J Am Dent Assoc. 125 (10): 1362–6. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1994.0180. PMID 7844301.

- Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide, S. Aust: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd. 2006. ISBN 978-0-9757919-2-9.

- Nielsen LJ, Lumholt P, Hölmich LR (October 2014). "[Local anaesthesia with vasoconstrictor is safe to use in areas with end-arteries in fingers, toes, noses and ears]". Ugeskrift for Laeger. 176 (44). PMID 25354008.

- "Lidocaine". Epocrates. Archived from the original on 2014-04-22.

- "Lidocaine Hydrochloride and 5% Dextrose Injection". Safety Labeling Changes. FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). January 2014. Archived from the original on 2013-04-03.

- "Lidocaine Viscous: Drug Safety Communication - Boxed Warning Required - Should Not Be Used to Treat Teething Pain". FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). June 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14.

- "Table 96–4. Drugs and Porphyria" (PDF). Merck Manual. Merck & Company, Inc. 2011. Archived from the original on 2014-04-20.

- "Lidocaine - N01BB02". Drug porphyrinogenicity monograph. The Norwegian Porphyria Centre and the Swedish Porphyria Centre. Archived from the original on 2014-04-20.

strong clinical evidence points to lidocaine as probably not porphyrinogenic

- Khan, M. Gabriel (2007). Cardiac Drug Therapy (7th ed.). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. ISBN 9781597452380.

- Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 840–4. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- Picard J, Ward SC, Zumpe R, Meek T, Barlow J, Harrop-Griffiths W (February 2009). "Guidelines and the adoption of 'lipid rescue' therapy for local anaesthetic toxicity". Anaesthesia. 64 (2): 122–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05816.x. PMID 19143686.

- Gulihar A, Robati S, Twaij H, Salih A, Taylor GJ (December 2015). "Articular cartilage and local anaesthetic: A systematic review of the current literature". Journal of Orthopaedics. 12 (Suppl 2): S200-10. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2015.10.005. PMC 4796530. PMID 27047224.

- Carterall, William A. (2001). "Molecular mechanisms of gating and drug block of sodium channels". Sodium Channels and Neuronal Hyperexcitability. Novartis Foundation Symposia. 241. pp. 206–225. doi:10.1002/0470846682.ch14. ISBN 9780470846681.

- Sheu SS, Lederer WJ (Oct 1985). "Lidocaine's negative inotropic and antiarrhythmic actions. Dependence on shortening of action potential duration and reduction of intracellular sodium activity". Circulation Research. 57 (4): 578–90. doi:10.1161/01.res.57.4.578. PMID 2412723.

- Lewin NA, Nelson LH (2006). "Chapter 61: Antidysrhythmics". In Flomenbaum N, Goldfrank LR, Hoffman RL, Howland MD, Lewin NA, Nelson LH (eds.). Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 963–4. ISBN 978-0-07-143763-9.

- Thomson PD, Melmon KL, Richardson JA, Cohn K, Steinbrunn W, Cudihee R, Rowland M (April 1973). "Lidocaine pharmacokinetics in advanced heart failure, liver disease, and renal failure in humans". Ann. Intern. Med. 78 (4): 499–508. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-78-4-499. PMID 4694036.

- Collinsworth KA, Kalman SM, Harrison DC (1974). "The clinical pharmacology of lidocaine as an antiarrhythymic drug". Circulation. 50 (6): 1217–30. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.50.6.1217. PMID 4609637.

- Löfgren N (1948). Studies on local anesthetics: Xylocaine: a new synthetic drug (Inaugural dissertation). Stockholm, Sweden: Ivar Heggstroms. OCLC 646046738.

- Löfgren N, Lundqvist B (1946). "Studies on local anaesthetics II". Svensk Kemisk Tidskrift. 58: 206–17.

- Wildsmith JAW (2011). "Lidocaine: A more complex story than 'simple' chemistry suggests" (PDF). The Proceedings of the History of Anaesthesia Society. 43: 9–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-04-22.

- "Lidocaine international forms and names". Drugs.com. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "Lidocaine HCL". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- "Lidocaine Ingredient Summary". Therapeutic Goods Administration. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Updating medicine ingredient names - list of affected ingredients". Therapeutic Goods Administration. 24 June 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- "The 2010 Prohibited List International Standard" (PDF). The World Anti-Doping Code. World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). 19 September 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2013.

- "New York Drug Threat Assessment". National Drug Intelligence Center. November 2002. Archived from the original on 2012-08-12.

- Pupka A, Sikora J, Mauricz J, Cios D, Płonek T (2009). "[The usage of synthol in the body building]". Polimery W Medycynie. 39 (1): 63–5. PMID 19580174.

- Bernardo NP; Siqueira MEPB; De Paiva MJN; Maia PP (2003). "Caffeine and other adulterants in seizures of street cocaine in Brazil". International Journal of Drug Policy. 14 (4): 331–4. doi:10.1016/S0955-3959(03)00083-5.

- "UNITED STATES of America, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. Luis A. CUELLO, Alvaro Bastides-Benitez, John Doe, a/k/a Hugo Hurtado, and Alvaro Carvajal, Defendants-Appellants". Docket No. 78-5314. United States Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit. 1979-07-25. Archived from the original on 2012-05-24.

- Winterman, Denise (2010-09-07). "How cutting drugs became big business". BBC News Online. BBC News Magazine. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "Revision Bulletin: Lidocaine and Prilocaine Cream–Revision to Related Compounds Test". The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. November 30, 2007. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013.

- Peterson, Michael E.; Talcott, Patricia A. (2013-08-07). Small Animal Toxicology. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0323241984. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- "FDA Freedom of Information Summary - Tributame" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-18.

External links

- "Lidocaine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Lidocaine Transdermal Patch". MedlinePlus.

- US patent 2441498, Nils Magnus Loefgren & Bengt Josef Lundqvist, "Alkyl glycinanilides", published 1948-05-11, issued 1948-05-11, assigned to ASTRA APOTEKARNES KEM FAB