Adverse drug reaction

An adverse drug reaction (ADR) is an injury caused by taking medication.[1] ADRs may occur following a single dose or prolonged administration of a drug or result from the combination of two or more drugs. The meaning of this term differs from the term "side effect" because side effects can be beneficial as well as detrimental.[2] The study of ADRs is the concern of the field known as pharmacovigilance. An adverse drug event (ADE) refers to any injury occurring at the time a drug is used, whether or not it is identified as a cause of the injury.[1] An ADR is a special type of ADE in which a causative relationship can be shown. ADRs are only one type of medication-related harm, as harm can also be caused by omitting to take indicated medications.[3]

| Adverse drug reaction | |

|---|---|

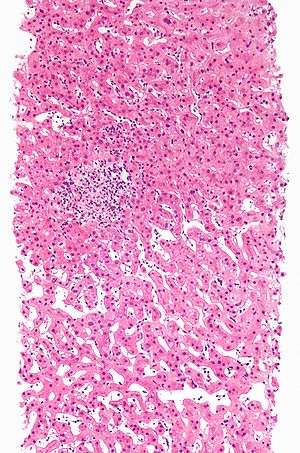

| |

| A rash due to a drug reaction |

Classification

ADRs may be classified by e.g. cause and severity.

Cause

- Type A: Augmented pharmacologic effects - dose dependent and predictable

- Type A reactions, which constitute approximately 80% of adverse drug reactions, are usually a consequence of the drug’s primary pharmacological effect (e.g. bleeding when using the anticoagulant warfarin) or a low therapeutic index of the drug (e.g. nausea from digoxin), and they are therefore predictable. They are dose-related and usually mild, although they may be serious or even fatal (e.g. intracranial bleeding from warfarin). Such reactions are usually due to inappropriate dosage, especially when drug elimination is impaired. The term ‘side effects’ is often applied to minor type A reactions.[4]

- Type B: Idiosyncratic

Types A and B were proposed in the 1970s,[5] and the other types were proposed subsequently when the first two proved insufficient to classify ADRs.[6]

Seriousness

The U.S Food and Drug Administration defines a serious adverse event as one when the patient outcome is one of the following:[7]

- Death

- Life-threatening

- Hospitalization (initial or prolonged)

- Disability - significant, persistent, or permanent change, impairment, damage or disruption in the patient's body function/structure, physical activities or quality of life.

- Congenital abnormality

- Requires intervention to prevent permanent impairment or damage

Severity is a point on an arbitrary scale of intensity of the adverse event in question. The terms "severe" and "serious", when applied to adverse events, are technically very different. They are easily confused but can not be used interchangeably, requiring care in usage.

A headache is severe if it causes intense pain. There are scales like "visual analog scale" that help clinicians assess the severity. On the other hand, a headache is not usually serious (but may be in case of subarachnoid haemorrhage, subdural bleed, even a migraine may temporally fit criteria), unless it also satisfies the criteria for seriousness listed above.

Location

Adverse effects may be local, i.e. limited to a certain location, or systemic, where medication has caused adverse effects throughout the systemic circulation.

For instance, some ocular antihypertensives cause systemic effects,[8] although they are administered locally as eye drops, since a fraction escapes to the systemic circulation.

Mechanisms

As research better explains the biochemistry of drug use, fewer ADRs are Type B and more are Type A. Common mechanisms are:

- Abnormal pharmacokinetics due to

- Synergistic effects between either

- a drug and a disease

- two drugs

- Antagonism effects between either

- a drug and a disease

- two drugs

Abnormal pharmacokinetics

Comorbid disease states

Various diseases, especially those that cause renal or hepatic insufficiency, may alter drug metabolism. Resources are available that report changes in a drug's metabolism due to disease states.[9]

The Medication Appropriateness Tool for Comorbid Health Conditions in Dementia[10] (MATCH-D) criteria warns that people with dementia are more likely to experience adverse effects, and that they are less likely to be able to reliably report symptoms.[11]

Genetic factors

Abnormal drug metabolism may be due to inherited factors of either Phase I oxidation or Phase II conjugation.[12][13] Pharmacogenomics is the study of the inherited basis for abnormal drug reactions.

Phase I reactions

Inheriting abnormal alleles of cytochrome P450 can alter drug metabolism. Tables are available to check for drug interactions due to P450 interactions.[14][15]

Inheriting abnormal butyrylcholinesterase (pseudocholinesterase) may affect metabolism of drugs such as succinylcholine[16]

Phase II reactions

Inheriting abnormal N-acetyltransferase which conjugated some drugs to facilitate excretion may affect the metabolism of drugs such as isoniazid, hydralazine, and procainamide.[15][16]

Inheriting abnormal thiopurine S-methyltransferase may affect the metabolism of the thiopurine drugs mercaptopurine and azathioprine.[15]

Interactions with other drugs

The risk of drug interactions is increased with polypharmacy.

Protein binding

These interactions are usually transient and mild until a new steady state is achieved.[17][18] These are mainly for drugs without much first-pass liver metabolism. The principal plasma proteins for drug binding are:[19]

- albumin

- α1-acid glycoprotein

- lipoproteins

Some drug interactions with warfarin are due to changes in protein binding.[19]

Cytochrome P450

Patients have abnormal metabolism by cytochrome P450 due to either inheriting abnormal alleles or due to drug interactions. Tables are available to check for drug interactions due to P450 interactions.[14]

Synergistic effects

An example of synergism is two drugs that both prolong the QT interval.

Assessing causality

Causality assessment is used to determine the likelihood that a drug caused a suspected ADR. There are a number of different methods used to judge causation, including the Naranjo algorithm, the Venulet algorithm and the WHO causality term assessment criteria. Each have pros and cons associated with their use and most require some level of expert judgement to apply.[20] An ADR should not be labeled as 'certain' unless the ADR abates with a challenge-dechallenge-rechallenge protocol (stopping and starting the agent in question). The chronology of the onset of the suspected ADR is important, as another substance or factor may be implicated as a cause; co-prescribed medications and underlying psychiatric conditions may be factors in the ADR.[2]

Assigning causality to a specific agent often proves difficult, unless the event is found during a clinical study or large databases are used. Both methods have difficulties and can be fraught with error. Even in clinical studies some ADRs may be missed as large numbers of test individuals are required to find that adverse drug reaction. Psychiatric ADRs are often missed as they are grouped together in the questionnaires used to assess the population.[21][22]

Monitoring bodies

Many countries have official bodies that monitor drug safety and reactions. On an international level, the WHO runs the Uppsala Monitoring Centre, and the European Union runs the European Medicines Agency (EMEA). In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for monitoring post-marketing studies. In Canada, the Marketed Health Products Directorate of Health Canada is responsible for the surveillance of marketed health products. In Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) conducts postmarket monitoring of therapeutic products. In the UK the Yellow Card Scheme was established in 1963.

Epidemiology

A study by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) found that in 2011, sedatives and hypnotics were a leading source for adverse drug events seen in the hospital setting. Approximately 2.8% of all ADEs present on admission and 4.4% of ADEs that originated during a hospital stay were caused by a sedative or hypnotic drug.[23] A second study by AHRQ found that in 2011, the most common specifically identified causes of adverse drug events that originated during hospital stays in the U.S. were steroids, antibiotics, opiates/narcotics, and anticoagulants. Patients treated in urban teaching hospitals had higher rates of ADEs involving antibiotics and opiates/narcotics compared to those treated in urban nonteaching hospitals. Those treated in private, nonprofit hospitals had higher rates of most ADE causes compared to patients treated in public or private, for-profit hospitals.[24]

In the U.S., females had a higher rate of ADEs involving opiates and narcotics than males in 2011, while male patients had a higher rate of anticoagulant ADEs. Nearly 8 in 1,000 adults aged 65 years or older experienced one of the four most common ADEs (steroids, antibiotics, opiates/narcotics, and anticoagulants) during hospitalization.[24] A study showed that 48% of patients had an adverse drug reaction to at least one drug, and pharmacist involvement helps to pick up adverse drug reactions.[25]

In 2012 McKinsey &Co. concluded that the cost of the 35 million preventable adverse drug events would be as high as US$115 billion.[26]

See also

- Alleged problems in the drug approval process

- Classification of Pharmaco-Therapeutic Referrals

- Drug therapy problems

- EudraVigilance (European Union)

- History of pharmacy

- Iatrogenesis

- Lethal dose

- List of withdrawn drugs

- Paradoxical reaction

- Polypharmacy

- Toxicity

- Toxicology

- The Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics

- Yellow Card Scheme (UK)

References

- "Guideline For Good Clinical Practice" (PDF). International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. 10 June 1996. p. 2. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Nebeker JR, Barach P, Samore MH (May 2004). "Clarifying adverse drug events: a clinician's guide to terminology, documentation, and reporting". Annals of Internal Medicine. 140 (10): 795–801. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-140-10-200405180-00017. PMID 15148066.

- Bose KS, Sarma RH (October 1975). "Delineation of the intimate details of the backbone conformation of pyridine nucleotide coenzymes in aqueous solution". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 66 (4): 1173–9. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(75)90482-9. PMID 2.

- Ritter, J M (2008). A Textbook of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Great Britain. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-340-90046-8.

- Rawlins MD, Thompson JW. Pathogenesis of adverse drug reactions. In: Davies DM, ed. Textbook of adverse drug reactions. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977:10.

- Aronson JK. Drug therapy. In: Haslett C, Chilvers ER, Boon NA, Colledge NR, Hunter JAA, eds. Davidson's principles and practice of medicine 19th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier Science, 2002:147-

- "MedWatch - What Is A Serious Adverse Event?". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- Rang, H. P. (2003). Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-443-07145-4. Page 146

- "Clinical Drug Use". Archived from the original on 1 November 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- "MATCH-D Medication Appropriateness Tool for Comorbid Health conditions during Dementia". www.match-d.com.au. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- Page AT, Potter K, Clifford R, McLachlan AJ, Etherton-Beer C (October 2016). "Medication appropriateness tool for co-morbid health conditions in dementia: consensus recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel". Internal Medicine Journal. 46 (10): 1189–1197. doi:10.1111/imj.13215. PMC 5129475. PMID 27527376.

- Phillips KA, Veenstra DL, Oren E, Lee JK, Sadee W (November 2001). "Potential role of pharmacogenomics in reducing adverse drug reactions: a systematic review". JAMA. 286 (18): 2270–9. doi:10.1001/jama.286.18.2270. PMID 11710893.

- Goldstein DB (February 2003). "Pharmacogenetics in the laboratory and the clinic". The New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (6): 553–6. doi:10.1056/NEJMe020173. PMID 12571264.

- "Drug-Interactions.com". Archived from the original on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- Weinshilboum R (February 2003). "Inheritance and drug response". The New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (6): 529–37. doi:10.1056/NEJMra020021. PMID 12571261.

- Evans WE, McLeod HL (February 2003). "Pharmacogenomics--drug disposition, drug targets, and side effects". The New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (6): 538–49. doi:10.1056/NEJMra020526. PMID 12571262.

- DeVane CL (2002). "Clinical significance of drug binding, protein binding, and binding displacement drug interactions". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 36 (3): 5–21. PMID 12473961.

- Benet LZ, Hoener BA (March 2002). "Changes in plasma protein binding have little clinical relevance". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 71 (3): 115–21. doi:10.1067/mcp.2002.121829. PMID 11907485.OVID full text summary table at OVID

- Sands CD, Chan ES, Welty TE (October 2002). "Revisiting the significance of warfarin protein-binding displacement interactions". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 36 (10): 1642–4. doi:10.1345/aph.1A208. PMID 12369572. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- Davies EC, Rowe PH, James S, et al. (2011). "An Investigation of Disagreement in Causality Assessment of Adverse Drug Reactions". Pharm Med. 25 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1007/bf03256843. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- Holvey C, Connolly A, Taylor D (August 2010). "Psychiatric side effects of non-psychiatric drugs". British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 71 (8): 432–6. doi:10.12968/hmed.2010.71.8.77664. PMID 20852483.

- Otsubo T (2003). "[Psychiatric complications of medicines]". Ryoikibetsu Shokogun Shirizu (40): 369–73. PMID 14626141.

- Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A (July 2013). "Origin of Adverse Drug Events in U.S. Hospitals, 2011" (HCUP Statistical Brief #158). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Weiss A.J.; Elixhauser A. (October 2013). "Characteristics of Adverse Drug Events Originating During the Hospital Stay, 2011" (HCUP Statistical Brief #164). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Yeung EY (October 2015). "Adverse drug reactions: a potential role for pharmacists". The British Journal of General Practice. 65 (639): 511.1–511. doi:10.3399/bjgp15X686821. PMC 4582849. PMID 26412813.

- http://www.gs1.org/docs/healthcare/McKinsey_Healthcare_Report_Strength_in_Unity.pdf

Further reading

External links

| Classification |

|---|