Varicose veins

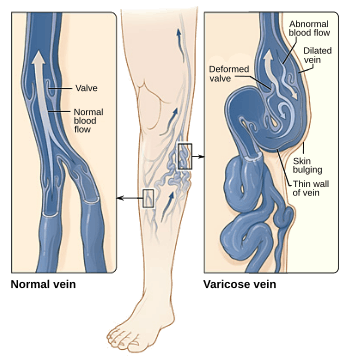

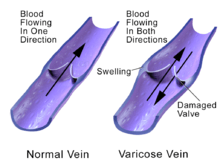

Varicose veins are superficial veins that have become enlarged and twisted.[2][1] Typically they occur just under the skin in the legs.[3] Usually they result in few symptoms but some may experience fullness or pain in the area.[2] Complications may include bleeding or superficial thrombophlebitis.[2][1] When varices occur in the scrotum it is known as a varicocele while those around the anus are known as hemorrhoids.[1] Varicose veins may negatively affect quality of life due to their physical, social and psychological effects.[5]

| Varicose veins | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leg affected by varicose veins | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Vascular surgery, dermatology[1] |

| Symptoms | None, fullness, pain in the area[2] |

| Complications | Bleeding, superficial thrombophlebitis[2][1] |

| Risk factors | Obesity, not enough exercise, leg trauma, family history, pregnancy[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on examination[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Arterial insufficiency, peripheral neuritis[4] |

| Treatment | Compression stockings, exercise, sclerotherapy, surgery[2][3] |

| Prognosis | Commonly reoccur[2] |

| Frequency | Very common[3] |

Often there is no specific cause.[2] Risk factors include obesity, not enough exercise, leg trauma, and a family history of the condition.[3] They also occur more commonly in pregnancy.[3] Occasionally they result from chronic venous insufficiency.[2] The underlying mechanism involves weak or damaged valves in the veins.[1] Diagnosis is typically by examination and may be supported by ultrasound.[2] In contrast spider veins involve the capillaries and are smaller.[1][6]

Treatment may involve life-style changes or medical procedures with the goal of improving symptoms and appearance.[1] Life-style changes may include compression stockings, exercise, elevating the legs, and weight loss.[1] Medical procedures include sclerotherapy, laser surgery, and vein stripping.[2][1] Following treatment there is often reoccurrence.[2]

Varicose veins are very common, affecting about 30% of people at some point in time.[3][7] They become more common with age.[3] Women are affected about twice as often as men.[6] Varicose veins have been described throughout history and have been treated with surgery since at least A.D. 400.[8]

Signs and symptoms

- Aching, heavy legs.[9]

- Appearance of spider veins (telangiectasia) in the affected leg.

- Ankle swelling, especially in the evening.[9]

- A brownish-yellow shiny skin discoloration near the affected veins.

- Redness, dryness, and itchiness of areas of skin, termed stasis dermatitis or venous eczema, because of waste products building up in the leg.

- Cramps[10] may develop especially when making a sudden move as standing up.

- Minor injuries to the area may bleed more than normal or take a long time to heal.

- In some people the skin above the ankle may shrink (lipodermatosclerosis) because the fat underneath the skin becomes hard.

- Restless legs syndrome appears to be a common overlapping clinical syndrome in people with varicose veins and other chronic venous insufficiency.

- Whitened, irregular scar-like patches can appear at the ankles. This is known as atrophie blanche.

Complications

Most varicose veins are reasonably benign, but severe varicosities can lead to major complications, due to the poor circulation through the affected limb.

- Pain, tenderness, heaviness, inability to walk or stand for long hours, thus hindering work

- Skin conditions / dermatitis which could predispose skin loss

- Skin ulcers especially near the ankle, usually referred to as venous ulcers.

- Development of carcinoma or sarcoma in longstanding venous ulcers. Over 100 reported cases of malignant transformation have been reported at a rate reported as 0.4% to 1%.[11]

- Severe bleeding from minor trauma, of particular concern in the elderly.

- Blood clotting within affected veins, termed superficial thrombophlebitis. These are frequently isolated to the superficial veins, but can extend into deep veins, becoming a more serious problem.

- Acute fat necrosis can occur, especially at the ankle of overweight people with varicose veins. Females have a higher tendency of being affected than males.

Causes

Varicose veins are more common in women than in men and are linked with heredity.[12] Other related factors are pregnancy, obesity, menopause, aging, prolonged standing, leg injury and abdominal straining. Varicose veins are unlikely to be caused by crossing the legs or ankles.[13] Less commonly, but not exceptionally, varicose veins can be due to other causes, such as post-phlebitic obstruction or incontinence, venous and arteriovenous malformations.[14]

Venous reflux is a significant cause. Research has also shown the importance of pelvic vein reflux (PVR) in the development of varicose veins. Varicose veins in the legs could be due to ovarian vein reflux.[15][16] Whiteley and his team reported that both ovarian and internal iliac vein reflux causes leg varicose veins and that this condition affects 14% of women with varicose veins or 20% of women who have had vaginal delivery and have leg varicose veins.[17] In addition, evidence suggests that failing to look for and treat pelvic vein reflux can be a cause of recurrent varicose veins.[18]

There is increasing evidence for the role of incompetent perforator veins (or "perforators") in the formation of varicose veins.[19] and recurrent varicose veins.[20]

Varicose veins could also be caused by hyperhomocysteinemia in the body, which can degrade and inhibit the formation of the three main structural components of the artery: collagen, elastin and the proteoglycans. Homocysteine permanently degrades cysteine disulfide bridges and lysine amino acid residues in proteins, gradually affecting function and structure. Simply put, homocysteine is a 'corrosive' of long-living proteins, i.e. collagen or elastin, or lifelong proteins, i.e. fibrillin. These long-term effects are difficult to establish in clinical trials focusing on groups with existing artery decline. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome and Parkes Weber syndrome are relevant for differential diagnosis.

Another cause is chronic alcohol consumption due to the vasodilatation side effect in relation to gravity and blood viscosity.[21]

Diagnosis

Clinical test

Clinical tests that may be used include:

- Trendelenburg test–to determine the site of venous reflux and the nature of the saphenofemoral junction

Investigations

Traditionally, varicose veins were investigated using imaging techniques only if there was a suspicion of deep venous insufficiency, if they were recurrent, or if they involved the saphenopopliteal junction. This practice is now less widely accepted. People with varicose veins should now be investigated using lower limbs venous ultrasonography. The results from a randomised controlled trial on patients with and without routine ultrasound have shown a significant difference in recurrence rate and reoperation rate at 2 and 7 years of follow-up.[22]

Stages

The CEAP (Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical, and Pathophysiological) Classification, developed in 1994 by an international ad hoc committee of the American Venous Forum, outlines these stages[23][24]

- C0 – no visible or palpable signs of venous disease

- C1 – telangectasia or reticular veins

- C2 – varicose veins.

- C3 – edema

- C4a – pigmentation or eczema

- C4b – lipodermatosclerosis, atrophie blanche

- C5 – healed venous ulcer

- C6 – active venous ulcer

Each clinical class is further characterised by a subscript depending upon whether the patient is symptomatic (S) or asymptomatic (A), e.g. C2S.[25]

Treatment

Treatment can be either conservative or active.

Active

Active treatments can be divided into surgical and non-surgical treatments. Newer methods including endovenous laser treatment, radiofrequency ablation and foam sclerotherapy appear to work as well as surgery for varices of the greater saphenous vein.[26]

Conservative

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) produced clinical guidelines in July 2013 recommending that all people with symptomatic varicose veins (C2S) and worse should be referred to a vascular service for treatment.[27] Conservative treatments such as support stockings should not be used unless treatment was not possible.

The symptoms of varicose veins can be controlled to an extent with the following:

- Elevating the legs often provides temporary symptomatic relief.

- Advice about regular exercise sounds sensible but is not supported by any evidence.[28]

- The wearing of graduated compression stockings with variable pressure gradients (Class II or III) has been shown to correct the swelling, nutritional exchange, and improve the microcirculation in legs affected by varicose veins.[29] They also often provide relief from the discomfort associated with this disease. Caution should be exercised in their use in patients with concurrent peripheral arterial disease.

- The wearing of intermittent pneumatic compression devices have been shown to reduce swelling and increase circulation

- Diosmin/hesperidin and other flavonoids.

- Anti-inflammatory medication such as ibuprofen or aspirin can be used as part of treatment for superficial thrombophlebitis along with graduated compression hosiery – but there is a risk of intestinal bleeding. In extensive superficial thrombophlebitis, consideration should be given to anti-coagulation, thrombectomy, or sclerotherapy of the involved vein.

- Topical gel application helps in managing symptoms related to varicose veins such as inflammation, pain, swelling, itching, and dryness.

Procedures

Stripping

Stripping consists of removal of all or part the saphenous vein (great/long or lesser/short) main trunk. The complications include deep vein thrombosis (5.3%),[30] pulmonary embolism (0.06%), and wound complications including infection (2.2%). There is evidence for the great saphenous vein regrowing after stripping.[31] For traditional surgery, reported recurrence rates, which have been tracked for 10 years, range from 5% to 60%. In addition, since stripping removes the saphenous main trunks, they are no longer available for use as venous bypass grafts in the future (coronary or leg artery vital disease).[32]

Other

Other surgical treatments are:

- CHIVA method is the ambulatory conservative haemodynamic correction of venous insufficiency. As of 2015 there is tentative evidence of benefits with a relatively low risk of side effects compared to vein stripping.[33]

- Ambulatory phlebectomy

- Vein ligation is done at the saphenofemoral junction after ligating the tributaries at the sephanofemoral junction without stripping the long saphenous vein provided the perforater veins are competent and absent DVT in the deep veins. With this method, the long saphenous vein is preserved.

- Cryosurgery- A cryoprobe is passed down the long saphenous vein following saphenofemoral ligation. Then the probe is cooled with NO2 or CO2 to −85o F. The vein freezes to the probe and can be retrogradely stripped after 5 seconds of freezing. It is a variant of Stripping. The only point of this technique is to avoid a distal incision to remove the stripper.[34]

Sclerotherapy

A commonly performed non-surgical treatment for varicose and "spider" leg veins is sclerotherapy, in which medicine (sclerosant) is injected into the veins to make them shrink. The medicines that are commonly used as sclerosants are polidocanol (POL branded Asclera in the United States, Aethoxysklerol in Australia), sodium tetradecyl sulphate (STS), Sclerodex (Canada), Hypertonic Saline, Glycerin and Chromated Glycerin. STS (branded Fibrovein in Australia) liquids can be mixed at varying concentrations of sclerosant and varying sclerosant/gas proportions, with air or CO2 or O2 to create foams. Foams may allow more veins to be treated per session with comparable efficacy. Their use in contrast to liquid sclerosant is still somewhat controversial. Sclerotherapy has been used in the treatment of varicose veins for over 150 years.[11] Sclerotherapy is often used for telangiectasias (spider veins) and varicose veins that persist or recur after vein stripping.[35][36] Sclerotherapy can also be performed using foamed sclerosants under ultrasound guidance to treat larger varicose veins, including the great saphenous and small saphenous veins.[37][38]

A 1996 study reported a 76% success rate at 24 months in treating saphenofemoral junction and great saphenous vein incompetence with STS 3% solution.[39] A Cochrane Collaboration review[36] concluded sclerotherapy was better than surgery in the short term (1 year) for its treatment success, complication rate and cost, but surgery was better after 5 years, although the research is weak.[40] A Health Technology Assessment found that sclerotherapy provided less benefit than surgery, but is likely to provide a small benefit in varicose veins without reflux.[41] This Health Technology Assessment monograph included reviews of epidemiology, assessment, and treatment, as well as a study on clinical and cost effectiveness of surgery and sclerotherapy.

Complications of sclerotherapy are rare but can include blood clots and ulceration. Anaphylactic reactions are "extraordinarily rare but can be life-threatening," and doctors should have resuscitation equipment ready.[42][43] There has been one reported case of stroke after ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy when an unusually large dose of sclerosant foam was injected.

Endovenous thermal ablation

There are three kinds of endovenous thermal ablation treatment possible: laser, radiofrequency, and steam.[44]

The Australian Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) in 2008 determined that endovenous laser treatment/ablation (ELA) for varicose veins "appears to be more effective in the short term, and at least as effective overall, as the comparative procedure of junction ligation and vein stripping for the treatment of varicose veins."[45] It also found in its assessment of available literature, that "occurrence rates of more severe complications such as DVT, nerve injury, and paraesthesia, post-operative infections, and haematomas, appears to be greater after ligation and stripping than after EVLT". Complications for ELA include minor skin burns (0.4%)[46] and temporary paresthesia (2.1%). The longest study of endovenous laser ablation is 39 months.

Two prospective randomized trials found speedier recovery and fewer complications after radiofrequency ablation (ERA) compared to open surgery.[47][48] Myers[49] wrote that open surgery for small saphenous vein reflux is obsolete. Myers said these veins should be treated with endovenous techniques, citing high recurrence rates after surgical management, and risk of nerve damage up to 15%. By comparison ERA has been shown to control 80% of cases of small saphenous vein reflux at 4 years, said Myers. Complications for ERA include burns, paraesthesia, clinical phlebitis and slightly higher rates of deep vein thrombosis (0.57%) and pulmonary embolism (0.17%). One 3-year study compared ERA, with a recurrence rate of 33%, to open surgery, which had a recurrence rate of 23%.

Steam treatment consists in injection of pulses of steam into the sick vein. This treatment which works with a natural agent (water) has similar results than laser or radiofrequency.[50] The steam presents a lot of post-operative advantages for the patient (good aesthetic results, less pain, etc.)[51]

ELA and ERA require specialized training for doctors and special equipment. ELA is performed as an outpatient procedure and does not require an operating theatre, nor does the patient need a general anaesthetic. Doctors use high-frequency ultrasound during the procedure to visualize the anatomical relationships between the saphenous structures. Some practitioners also perform phlebectomy or ultrasound guided sclerotherapy at the time of endovenous treatment. Follow-up treatment to smaller branch varicose veins is often needed in the weeks or months after the initial procedure. Steam is a very promising treatment for both doctors (easy introduction of catheters, efficient on recurrences, ambulatory procedure, easy and economic procedure) and patients (less post-operative pain, a natural agent, fast recovery to daily activities).

Epidemiology

This condition is most common after age 50.[52] It is more prevalent in females. There is a hereditary role. It has been seen in smokers, those who have chronic constipation, and in people with occupations which necessitate long periods of standing such as lecturers, nurses, conductors (musical and bus), stage actors, umpires (cricket, javelin, etc.), the Queen's guard, lectern orators, security guards, traffic police officers, vendors, surgeons, etc.[53]

References

- "Varicose Veins". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- "Varicose Veins - Cardiovascular Disorders". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- "Varicose Veins". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Buttaro, Terry Mahan; Trybulski, JoAnn; Polgar-Bailey, Patricia; Sandberg-Cook, Joanne (2016). BOPOD - Primary Care: A Collaborative Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 609. ISBN 9780323355216.

- Lumley, E; Phillips, P; Aber, A; Buckley-Woods, H; Jones, GL; Michaels, JA (April 2019). "Experiences of living with varicose veins: A systematic review of qualitative research". Journal of clinical nursing. 28 (7–8): 1085–1099. doi:10.1111/jocn.14720. PMID 30461103.

- "Varicose veins and spider veins". womenshealth.gov. 15 December 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- "Varicose veins Introduction - Health encyclopaedia". NHS Direct. 8 November 2007. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Gloviczki, Peter (2008). Handbook of Venous Disorders : Guidelines of the American Venous Forum Third Edition. CRC Press. p. 6. ISBN 9781444109689.

- Tisi, Paul V (5 January 2011). "Varicose veins". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2011. ISSN 1752-8526. PMC 3217733. PMID 21477400.

- Chandra, Abe. "Clinical review of varicose veins: epidemiology, diagnosis and management | GPonline". www.gponline.com.

- Goldman M. (1995) Sclerotherapy, Treatment of Varicose and Telangiectatic Leg Veins. Hardcover Text, 2nd Ed.

- Ng M, Andrew T, Spector T, Jeffery S (2005). "Linkage to the FOXC2 region of chromosome 16 for varicose veins in otherwise healthy, unselected sibling pairs". Journal of Medical Genetics. 42 (3): 235–9. doi:10.1136/jmg.2004.024075. PMC 1736007. PMID 15744037.

- Kate Griesmann (March 16, 2011). "Myth or Fact: Crossing Your Legs Causes Varicose Veins". Duke University Health System. Archived from the original on 2014-03-05. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- Franceschi, Claude (1996) "Physiopathologie Hémodynamique de l'Insuffisance veineuse", p. 49 in Chirurgie des veines des Membres Inférieurs, AERCV editions 23 rue Royale 75008 Paris France.

- Hobbs JT (October 2005). "Varicose veins arising from the pelvis due to ovarian vein incompetence". Int J Clin Pract. Int J Clin Pract. 59 (10): 1195–203. doi:10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00631.x. PMID 16178988.

- Giannoukas AD, Dacie JE, Lumley JS (July 2000). "Recurrent varicose veins of both lower limbs due to bilateral ovarian vein incompetence". Ann Vasc Surg. 14 (4): 397–400. doi:10.1007/s100169910075. PMID 10943794.

- Marsh P, Holdstock J, Harrison C, Smith C, Price BA, Whiteley MS (June 2009). "Pelvic vein reflux in female patients with varicose veins: comparison of incidence between a specialist private vein clinic and the vascular department of a National Health Service District General Hospital". Phlebology. 24 (3): 108–13. doi:10.1258/phleb.2008.008041. PMID 19470861.

- A.M. Whiteley; D.C. Taylor; S.J. Dos Santos; M.S. Whiteley (2014). "Pelvic Venous Reflux is a Major Contributory Cause of Recurrent Varicose Veins in More Than a Quarter of Women". Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders. 2 (4): 390–396. doi:10.1016/j.jvsv.2014.05.003. PMID 26993544.

- Whiteley MS (September 2014). "Part One: For the Motion. Venous Perforator Surgery is Proven and Does Reduce Recurrences". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 48 (3): 239–42. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.06.044. PMID 25132056.

- Rutherford EE, Kianifard B, Cook SJ, Holdstock JM, Whiteley MS (May 2001). "Incompetent perforating veins are associated with recurrent varicose veins". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 21 (5): 458–60. doi:10.1053/ejvs.2001.1347. PMID 11352523.

- Pathophysiology for the Boards and Wards, Fourth Edition

- Blomgren L, Johansson G, Emanuelsson L, Dahlberg-Åkerman A, Thermaenius P, Bergqvist D (Aug 2011). "Late follow-up of a randomized trial of routine duplex imaging before varicose vein surgery". Br J Surg. 98 (8): 1112–6. doi:10.1002/bjs.7579. PMID 21618499.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Diagnosis and management of varicose veins in the legs: NICE guideline" British Journal of General Practice, 2014, Norma O’Flynn, Mark Vaughan and Kate Kelley, accessed 5 November 2018

- "Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders" by B Eklöf, jvascsurg.org, 2004, accessed 5 November 2018

- Bailey & Love's Short Practice of Surgery (26th ed.).

- Nesbitt, C; Bedenis, R; Bhattacharya, V; Stansby, G (Jul 30, 2014). "Endovenous ablation (radiofrequency and laser) and foam sclerotherapy versus open surgery for great saphenous vein varices". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD005624. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005624.pub3. PMID 25075589.

- NICE (July 23, 2013). "Varicose veins in the legs: The diagnosis and management of varicose veins. 1.2 Referral to a vascular service". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- Campbell B (2006). "Varicose veins and their management". BMJ. 333 (7562): 287–92. doi:10.1136/bmj.333.7562.287. PMC 1526945. PMID 16888305.

- Curri SB et al. (1989) "Changes of cutaneous microcirculation from elasto-compression in chronic venous insufficiency". In Davy A and Stemmer R (eds.) Phlebology '89, Montrouge, France, 'John Libbey Eurotext.

- van Rij AM, Chai J, Hill GB, Christie RA (2004). "Incidence of deep vein thrombosis after varicose vein surgery". Br J Surg. 91 (12): 1582–5. doi:10.1002/bjs.4701. PMID 15386324.

- Munasinghe A, Smith C, Kianifard B, Price BA, Holdstock JM, Whiteley MS (2007). "Strip-tract revascularization after stripping of the great saphenous vein". Br J Surg. 94 (7): 840–3. doi:10.1002/bjs.5598. PMID 17410557.

- Hammarsten J, Pedersen P, Cederlund CG, Campanello M (1990). "Long saphenous vein saving surgery for varicose veins. A long-term follow-up". Eur J Vasc Surg. 4 (4): 361–4. doi:10.1016/S0950-821X(05)80867-9. PMID 2204548.

- Bellmunt-Montoya, S; Escribano, JM; Dilme, J; Martinez-Zapata, MJ (29 June 2015). "CHIVA method for the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD009648. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009648.pub3. PMC 7097730. PMID 26121003.

- Shouten R, Mollen RM, Kuijpers HC (2006). "A comparison between cryosurgery and conventional stripping in varicose vein surgery: perioperative features and complications". Annals of Vascular Surgery. 20 (3): 306–11. doi:10.1007/s10016-006-9051-x. PMID 16779510.

- Pak, L. K. et al. "Veins & Lymphatics," in Lange's Current Surgical Diagnosis & Treatment, 11th ed., McGraw-Hill.

- Tisi, Paul V; Beverley, Catherine; Rees, Angie (2006). Tisi, Paul V (ed.). "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Chapter: Injection sclerotherapy for varicose veins". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD001732. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001732.pub2. PMID 17054141.

- Thibault, Paul (2007) Sclerotherapy and Ultrasound-Guided Sclerotherapy, The Vein Book, John J. Bergan (ed.).

- Padbury A, Benveniste GL (December 2004). "Foam echosclerotherapy of the small saphenous vein". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Phlebology. 8 (1).

- Kanter A, Thibault P (1996). "Saphenofemoral incompetence treated by ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy". Dermatol Surg. 22 (7): 648–52. doi:10.1016/1076-0512(96)00173-2. PMID 8680788.

- Rigby KA, Palfreyman SJ, Beverley C, Michaels JA (2004). Rigby, Kathryn A (ed.). "Surgery versus sclerotherapy for the treatment of varicose veins". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD004980. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004980. PMID 15495134.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Michaels JA; Campbell WB; Brazier JE; MacIntyre, JB; Palfreyman, SJ; Ratcliffe, J; Rigby, K (2006). "Randomised clinical trial, observational study and assessment of cost-effectiveness of the treatment of varicose veins (REACTIV trial)". Health Technol Assess. 10 (13): 1–196, iii–iv. doi:10.3310/hta10130. PMID 16707070. Archived from the original on 2010-12-29. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- Finkelmeier, William R. (2004) "Sclerotherapy", Ch. 12 in ACS Surgery: Principles & Practice, WebMD, ISBN 0-9748327-4-X.

- Scurr JR, Fisher RK, Wallace SB (2007). "Anaphylaxis Following Foam Sclerotherapy: A Life Threatening Complication of Non Invasive Treatment For Varicose Veins". EJVES Extra. 13 (6): 87–89. doi:10.1016/j.ejvsextra.2007.02.005.

- Malskat WS, Stokbroekx MA, van der Geld CW, Nijsten TE, van den Bos RR (March 29, 2014). "Temperature Profiles of 980- and 1,470-nm Endovenous Laser Ablation, Endovenous Radiofrequency Ablation and Endovenous Steam Ablation". Lasers Med Sci. 29 (2): 423–9. doi:10.1007/s10103-013-1449-4. PMID 24292197.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Medical Services Advisory Committee, ELA for varicose veins. MSAC application 1113, Dept of Health and Ageing, Commonwealth of Australia, 2008.

- Elmore FA, Lackey D (2008). "Effectiveness of ELA in eliminating superficial venous reflux". Phlebology. 23 (1): 21–31. doi:10.1258/phleb.2007.007019. PMID 18361266.

- Rautio TT, Perälä JM, Wiik HT, Juvonen TS, Haukipuro KA (2002). "Endovenous obliteration with radiofrequency-resistive heating for greater saphenous vein insufficiency: a feasibility study". J Vasc Interv Radiol. 13 (6): 569–75. doi:10.1016/S1051-0443(07)61649-2. PMID 12050296.

- Lurie F; Creton D; Eklof B; Kabnick, L.S.; Kistner, R.L.; Pichot, O.; Sessa, C.; Schuller-Petrovic, S. (2005). "Prospective randomised study of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration (closure) versus ligation and vein stripping (EVOLVeS): two-year follow-up". Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 29 (1): 67–73. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.09.019. PMID 15570274.

- Myers, Kenneth (December 2004). "An opinion — surgery for small saphenous reflux is obsolete!". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Phlebology. 8 (1).

- Van den Bos, RR; Malskat, WS; De Maeseneer, MG; De Roos, KP; Groeneweg, DA; Kockaert, MA; Neumann, HA; Nijsten, T (2014-06-30). "Randomized clinical trial of endovenous laser ablation versus steam ablation (LAST trial) for great saphenous veins". Br J Surg. 101 (9): 1077–1083. doi:10.1002/bjs.9580. PMID 24981585.

- Milleret, René (2011). "Obliteration of varicose veins with superheated steam". Phlebolymphology. 19 (4): 174–181.

- Tamparo, Carol (2011). Fifth Edition: Diseases of the Human Body. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Company. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-8036-2505-1.

- Bailey and Love textbook of Surgery

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |