Endoscopy

An endoscopy (looking inside) is a procedure used in medicine to look inside the body.[1] The endoscopy procedure uses an endoscope to examine the interior of a hollow organ or cavity of the body. Unlike many other medical imaging techniques, endoscopes are inserted directly into the organ.

| Endoscope | |

|---|---|

An example of a flexible endoscope | |

| MeSH | D004724 |

| OPS-301 code | 1-40...1-49, 1-61...1-69 |

| MedlinePlus | 003338 |

There are many types of endoscopes. Depending on the site in the body and type of procedure an endoscopy may be performed either by a doctor or a surgeon. A patient may be fully conscious or anaesthetised during the procedure. Most often the term endoscopy is used to refer to an examination of the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract, known as an esophagogastroduodenoscopy.[2]

For non-medical use, similar instruments are called borescopes.

History

The self-illuminated endoscope was developed at Glasgow Royal Infirmary in Scotland (one of the first hospitals to have mains electricity) in 1894/5 by Dr John Macintyre as part of his specialization in investigation of the larynx.[3]

Medical uses

Endoscopy may be used to investigate symptoms in the digestive system including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, difficulty swallowing, and gastrointestinal bleeding.[4] It is also used in diagnosis, most commonly by performing a biopsy to check for conditions such as anemia, bleeding, inflammation, and cancers of the digestive system.[4] The procedure may also be used for treatment such as cauterization of a bleeding vessel, widening a narrow esophagus, clipping off a polyp or removing a foreign object.[4]

Specialty professional organizations which specialize in digestive problems advise that many patients with Barrett's esophagus are too frequently receiving endoscopies.[5] Such societies recommend that patients with Barrett's esophagus and no cancer symptoms after two biopsies receive biopsies as indicated and no more often than the recommended rate.[6][7]

Applications

Health care providers can use endoscopy to review any of the following body parts:

- The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract):

- oesophagus, stomach and duodenum (esophagogastroduodenoscopy)

Esophageal Bougie Dilator

Esophageal Bougie Dilator - small intestine (enteroscopy)

- large intestine/colon (colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy)

- Magnification endoscopy

- bile duct

- endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), duodenoscope-assisted cholangiopancreatoscopy, intraoperative cholangioscopy

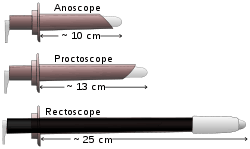

- rectum (rectoscopy) and anus (anoscopy), both also referred to as (proctoscopy)

- The respiratory tract

- The nose (rhinoscopy)

- The upper respiratory tract (laryngoscopy)

- The lower respiratory tract (bronchoscopy)

- The ear (otoscope)

- The urinary tract (cystoscopy)

- The female reproductive system (gynoscopy)

- The cervix (colposcopy)

- The uterus (hysteroscopy)

- The fallopian tubes (falloposcopy)

- Normally closed body cavities (through a small incision):

- The abdominal or pelvic cavity (laparoscopy)

- The interior of a joint (arthroscopy)

- Organs of the chest (thoracoscopy and mediastinoscopy)

Endoscopy is used for many procedures:

- During pregnancy

- Plastic surgery

- Panendoscopy (or triple endoscopy)

- Combines laryngoscopy, esophagoscopy, and bronchoscopy

- Orthopedic surgery

- Hand surgery, such as endoscopic carpal tunnel release

- Knee surgery, such as anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Epidural space (Epiduroscopy)

- Bursae (Bursectomy)

- Endodontic surgery

- Maxillary sinus surgery

- Apicoectomy

- Endoscopic endonasal surgery

- Endoscopic spinal surgery

An Endoscopy is a simple procedure which allows a doctor to look inside human bodies using an instrument called an endoscope. A cutting tool can be attached to the end of the endoscope, and the apparatus can then be used to perform surgery. This type of surgery is called Key hole surgery, and usually leaves only a tiny scar externally.

Application in other fields

- The planning and architectural community use architectural endoscopy for pre-visualization of scale models of proposed buildings and cities

- Internal inspection of complex technical systems (borescope)

- Endoscopes are also a tool helpful in the examination of improvised explosive devices by bomb disposal personnel.

- The FBI uses endoscopes for conducting surveillance via tight spaces.

Risks

The main risks are infection, over-sedation, perforation, or a tear of the stomach or esophagus lining and bleeding.[8] Although perforation generally requires surgery, certain cases may be treated with antibiotics and intravenous fluids. Bleeding may occur at the site of a biopsy or polyp removal. Such typically minor bleeding may simply stop on its own or be controlled by cauterisation. Seldom does surgery become necessary. Perforation and bleeding are rare during gastroscopy. Other minor risks include drug reactions and complications related to other diseases the patient may have. Consequently, patients should inform their doctor of all allergic tendencies and medical problems. Occasionally, the site of the sedative injection may become inflamed and tender for a short time. This is usually not serious and warm compresses for a few days are usually helpful. While any of these complications may possibly occur, it is good to remember that each of them occurs quite infrequently. A doctor can further discuss risks with the patient with regard to the particular need for gastroscopy.

After the endoscopy

After the procedure, the patient will be observed and monitored by a qualified individual in the endoscopy room, or a recovery area, until a significant portion of the medication has worn off. Occasionally the patient is left with a mild sore throat, which may respond to saline gargles, or chamomile tea. It may last for weeks or not happen at all. The patient may have a feeling of distention from the insufflated air that was used during the procedure. Both problems are mild and fleeting. When fully recovered, the patient will be instructed when to resume their usual diet (probably within a few hours) and will be allowed to be taken home. Where sedation has been used, most facilities mandate that the patient be taken home by another person and that he or she not drive or handle machinery for the remainder of the day. Patients who have had an endoscopy without sedation are able to leave unassisted.

Endoscope

An endoscope can consist of:

- a rigid or flexible tube.

- a light delivery system to illuminate the organ or object under inspection. The light source is normally outside the body and the light is typically directed via an optical fiber system.

- a lens system transmitting the image from the objective lens to the viewer, typically a relay lens system in the case of rigid endoscopes or a bundle of fiberoptics in the case of a fiberscope.

- an eyepiece. Modern instruments may be videoscopes, with no eyepiece. A camera transmits image to a screen for image capture.

- an additional channel to allow entry of medical instruments or manipulators.

Patients undergoing the procedure may be offered sedation, which includes its own risks.

History

The first endoscope was developed in 1806 by Philipp Bozzini in Mainz with his introduction of a "Lichtleiter" (light conductor) "for the examinations of the canals and cavities of the human body".[9] However, the Vienna Medical Society disapproved of such curiosity.[10] The first to use an endoscope in a successful operation was Antonin Jean Desormeaux whose invention was the state of the art before the invention of electricity.

The use of electric light was a major step in the improvement of endoscopy. The first such lights were external although sufficiently capable of illumination to allow cystoscopy, hysteroscopy and sigmoidoscopy as well as examination of the nasal (and later thoracic) cavities as was being performed routinely in human patients by Sir Francis Cruise (using his own commercially available endoscope) by 1865 in the Mater Misericordiae Hospital in Dublin, Ireland.[11] Later, smaller bulbs became available making internal light possible, for instance in a hysteroscope by Charles David in 1908.[12]

Hans Christian Jacobaeus has been given credit for the first large published series of endoscopic explorations of the abdomen and the thorax with laparoscopy (1912) and thoracoscopy (1910)[13] although the first reported thoracoscopic examination in a human was also by Cruise.[14]

Laparoscopy was used in the diagnosis of liver and gallbladder disease by Heinz Kalk in the 1930s.[15] Hope reported in 1937 on the use of laparoscopy to diagnose ectopic pregnancy.[16] In 1944, Raoul Palmer placed his patients in the Trendelenburg position after gaseous distention of the abdomen and thus was able to reliably perform gynecologic laparoscopy.[17]

Wolf and Storz

Georg Wolf (1873–1938) a Berlin manufacturer of rigid endoscopes, established in 1906, produced the Sussmann flexible gastroscope in 1911 (Modlin, Farhadi-Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 2000).[18] Karl Storz began producing instruments for ENT specialists in 1945 through his company, Karl Storz GmbH.[19]

Fiber optics

Basil Hirschowitz and Larry Curtiss invented the first fiber optic endoscope in 1957.[20] Earlier in the 1950s Harold Hopkins had designed a "fibroscope" consisting of a bundle of flexible glass fibres able to coherently transmit an image. This proved useful both medically and industrially, and subsequent research led to further improvements in image quality. Further innovations included using additional fibres to channel light to the objective end from a powerful external source, thereby achieving the high level of full spectrum illumination that was needed for detailed viewing, and colour photography.

The previous practice of a small filament lamp on the tip of the endoscope had left the choice of either viewing in a dim red light or increasing the light output - which carried the risk of burning the inside of the patient. Alongside the advances to the optics, the ability to 'steer' the tip was developed, as well as innovations in remotely operated surgical instruments contained within the body of the endoscope itself. This was the beginning of "key-hole surgery" as we know it today.

Rod-lens endoscopes

There were physical limits to the image quality of a fibroscope. A bundle of say 50,000 fibers gives effectively only a 50,000-pixel image, and continued flexing from use breaks fibers and so progressively loses pixels. Eventually so many are lost that the whole bundle must be replaced (at considerable expense). Harold Hopkins realised that any further optical improvement would require a different approach. Previous rigid endoscopes suffered from low light transmittance and poor image quality. The surgical requirement of passing surgical tools as well as the illumination system within the endoscope's tube - which itself is limited in dimensions by the human body - left very little room for the imaging optics. The tiny lenses of a conventional system required supporting rings that would obscure the bulk of the lens area; they were difficult to manufacture and assemble and optically nearly useless.

The elegant solution that Hopkins invented was to fill the air-spaces between the 'little lenses' with rods of glass. These fitted exactly the endoscope's tube, making them self-aligning, and required no other support. This allowed the little lenses to be dispensed with altogether. The rod-lenses were much easier to handle and used the maximum possible diameter available.

With the appropriate curvature and coatings to the rod ends and optimal choices of glass-types, all calculated and specified by Hopkins, the image quality was transformed - even with tubes of only 1mm in diameter. With a high quality 'telescope' of such small diameter the tools and illumination system could be comfortably housed within an outer tube. Once again it was Karl Storz who produced the first of these new endoscopes as part of a long and productive partnership between the two men.[21]

Whilst there are regions of the body that will always require flexible endoscopes (principally the gastrointestinal tract), the rigid rod-lens endoscopes have such exceptional performance that they are still the preferred instrument and have enabled modern key-hole surgery. (Harold Hopkins was recognized and honoured for his advancement of medical-optic by the medical community worldwide. It formed a major part of the citation when he was awarded the Rumford Medal by the Royal Society in 1984.)

By measuring absorption of light by the blood (by passing the light through one fibre and collecting the light through another fibre) a doctor can estimate the proportion of haemoglobin in the blood and diagnose ulceration in the stomach.

Endoscope reprocessing

High level disinfection of flexible endoscopes is required by all national guideline issuing bodies.[22] The high level disinfection of endoscopes occurs during a multi-step process called reprocessing. Reprocessing endoscopes involves over 100 individuals steps.[23] These steps can be broken down into broad categories of pre-cleaning, leak testing, manual cleaning, cleaning verification, visual inspection, high level disinfection, rinsing, drying, and storage.[24] Failure to perform all of these steps correctly can lead to residual contamination remaining on endoscopes.

In the UK, stringent guidelines exist regarding the decontamination and disinfection of flexible endoscopes, the most recent being CfPP 01–06, released in 2013[25]

Rigid endoscopes, such as an Arthroscope, can be sterilized in the same way as surgical instruments, whereas heat labile flexible endoscopes cannot.[26]

Recent developments

With the application of robotic systems, telesurgery was introduced as the surgeon could be at a site far removed from the patient. The first transatlantic surgery has been called the Lindbergh Operation.

Wireless oesophageal pH measuring devices can now be placed endoscopically, to record ph trends in an area remotely.

Endoscopy VR simulators

Virtual reality simulators are being developed for training doctors on various endoscopy skills.[27]

Disposable endoscopy

Disposable endoscopy is an emerging category of endoscopic instruments. Recent developments[28] have allowed the manufacture of endoscopes inexpensive enough to be used on a single patient only. It is meeting a growing demand to lessen the risk of cross contamination and hospital acquired diseases. A European consortium of the SME is working on the DUET (disposable use of endoscopy tool) project to build a disposable endoscope.[29]

Capsule endoscopy

Capsule endoscopes are pill-sized imaging devices that are swallowed by a patient and then record images of the gastrointestinal tract as they pass through naturally. Images are typically retrieved via wireless data transfer to an external receiver.

Augmented reality

The endoscopic image can be combined with other image sources to provide the surgeon with additional information. For instance, the position of an anatomical structure or tumor might be shown in the endoscopic video.[30]

New imaging modalities

Emerging endoscope technologies measure additional properties of light to improve contrast, such as optical polarization,[31] optical phase,[32] and additional wavelengths of light (hyperspectral endoscopy).[33]

See also

References

- "Endoscopy". British Medical Association Complete Family Health Encyclopedia. Dorling Kindersley Limited. 1990.

- "Endoscopy". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "The Scottish Society of the History of Medicine" (PDF).

- Staff (2012). "Upper endoscopy". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- American Gastroenterological Association, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Gastroenterological Association, archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2012, retrieved August 17, 2012

- Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, Inadomi JM, Shaheen NJ (March 2011). "American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett's esophagus". Gastroenterology. 140 (3): 1084–91. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.030. PMID 21376940.

- Wang KK, Sampliner RE (March 2008). "Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett's esophagus". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 103 (3): 788–97. PMID 18341497.

- "Endoscopy". NHS Choices. NHS Gov.UK. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- Bozzini, Philipp (1806). "Lichtleiter, eine Erfindung zur Anschauung innerer Teile und Krankheiten, nebst der Abbildung" [Light conductor, an invention for examining internal parts and diseases, together with illustrations]. Journal der Practischen Arzneykunde und Wundarzneykunst (in German). 24: 107–24.

- Yamada T (2009-01-22). Atlas of Gastroenterology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-0342-1.

- Caniggia A, Nuti R, Lore F, Martini G, Turchetti V, Righi G (April 1990). "Long-term treatment with calcitriol in postmenopausal osteoporosis". Metabolism. 39 (4 Suppl 1): 43–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.223.345. JSTOR 25204557. PMC 2325571. PMID 2325571.

- Shawki O, Deshmukh S, Pacheco LA (2017). Mastering the Techniques in Hysteroscopy. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-93-86150-49-3.

- Litynski GS (Jan–Mar 1997). "Laparoscopy--the early attempts: spotlighting Georg Kelling and Hans Christian Jacobaeus". JSLS. 1 (1): 83–5. PMC 3015224. PMID 9876654.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Gordon S (2014). "Art. VIII.—Clinical reports of rare cases, occurring in the Whitworth and Hardwicke Hospitals". Dublin Quarterly Journal of Medical Science. 41 (1): 83–99. doi:10.1007/BF02946459.

- Wildhirt E, Kalk H (1977). Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 11. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. p. 60. ISBN 978-3-428-00192-7.

- Balen AH, Creighton SM, Davies MC, MacDougall J, Stanhope R (2004-04-01). Paediatric and Adolescent Gynaecology: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Cambridge University Press. pp. 131–. ISBN 978-1-107-32018-5.

- Litynski GS (Jul–Sep 1997). "Raoul Palmer, World War II, and transabdominal coelioscopy. Laparoscopy extends into gynecology". Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 1 (3): 289–92. PMC 3016739. PMID 9876691.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- "About Richard Wolf Germany". Richard Wolf Medical Instruments.

- Nezhat C (2005). "Chapter 19. 1960's". Nezhat's History of Endoscopy. Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons.

- Edmonson JM (March 1991). "History of the instruments for gastrointestinal endoscopy". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 37 (2 Suppl): S27–56. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(91)70910-3. PMID 2044933.

- "History". Harold Hopkins Society.

- Ofstead CL, Wetzler HP, Heymann OL, Johnson EA, Eiland JE, Shaw MJ (February 2017). "Longitudinal assessment of reprocessing effectiveness for colonoscopes and gastroscopes: Results of visual inspections, biochemical markers, and microbial cultures". American Journal of Infection Control. 45 (2): e26–e33. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2016.10.017. PMID 28159069.

- Ofstead CL, Wetzler HP, Snyder AK, Horton RA (2010). "Endoscope reprocessing methods: a prospective study on the impact of human factors and automation". Gastroenterology Nursing. 33 (4): 304–11. doi:10.1097/SGA.0b013e3181e9431a. PMID 20679783.

- Herrin A, Loyola M, Bocian S, Diskey A, Friis CM, Herron-Rice L, Juan MR, Schmelzer M, Selking S (2016). "Standards of Infection Prevention in Reprocessing Flexible Gastrointestinal Endoscopes". Gastroenterology Nursing. 39 (5): 404–18. doi:10.1097/SGA.0000000000000266. PMID 27684640. S2CID 37069977.

- "Health Technical Memorandum 01-06: Decontamination of exible endoscopes Part C: Operational management" (PDF). United Kingdom Department of Health. March 2016.

- Sabnis RB, Bhattu A, Vijaykumar M (March 2014). "Sterilization of endoscopic instruments". Current Opinion in Urology. 24 (2): 195–202. doi:10.1097/MOU.0000000000000034. PMID 24451088.

- "Overview of Endoscopy Haptics Simulator Project". M2D2 Laboratory, Indian Institute of Science. YouTube.

- "Dokument nicht gefunden". Archived from the original on 2011-07-20.

- "Development of a Disposable Use Endoscopy Tool". 2018-03-26. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23.

- Augmented Reality: Path guidance to craniopharyngioma on YouTube

- Manhas S, Vizet J, Deby S, Vanel JC, Boito P, Verdier M, De Martino A, Pagnoux D (February 2015). "Demonstration of full 4×4 Mueller polarimetry through an optical fiber for endoscopic applications". Optics Express. 23 (3): 3047–54. Bibcode:2015OExpr..23.3047M. doi:10.1364/OE.23.003047. PMID 25836165.

- Gordon, GSD; Joseph, J; Alcolea, MP; Sawyer, T; Macfaden, AJ; Williams, C; Fitzpatrick, CRM; Jones, PH; di Pietro, M; Fitzgerald, RC; Wilkinson, TD; Bohndiek, SE (2018). "Quantitative phase and polarisation endoscopy applied to detection of early oesophageal tumourigenesis". Journal of Biomedical Optics. 24 (12): 1–13. arXiv:1811.03977. doi:10.1117/1.JBO.24.12.126004. PMC 7006047. PMID 31840442.

- Kester RT, Bedard N, Gao L, Tkaczyk TS (May 2011). "Real-time snapshot hyperspectral imaging endoscope". Journal of Biomedical Optics. 16 (5): 056005–056005–12. Bibcode:2011JBO....16e6005K. doi:10.1117/1.3574756. PMC 3107836. PMID 21639573.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Endoscopy. |

- The Atlas of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy endoatlas.com

- El Salvador Atlas of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

- Gastrolab: Site in English, Swedish and Finnish with gastrointestinal endoscopy photolibrary

- Preventing cross-contamination from flexible endoscopes massdevice.com

- Advances in Endoscopy advancedimagingpro.com