Psilocybe cubensis

Psilocybe cubensis is a species of psychedelic mushroom whose principal active compounds are psilocybin and psilocin. Commonly called shrooms, magic mushrooms, golden tops, cubes, or gold caps, it belongs to the fungus family Hymenogastraceae and was previously known as Stropharia cubensis. It is the most well known psilocybin mushroom due to its wide distribution and ease of cultivation.

| Psilocybe cubensis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Agaricales |

| Family: | Hymenogastraceae |

| Genus: | Psilocybe |

| Species: | P. cubensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Psilocybe cubensis | |

| |

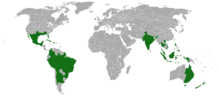

| Approximate Range of Psilocybe cubensis | |

| Psilocybe cubensis | |

|---|---|

float | |

| gills on hymenium | |

| cap is convex or flat | |

| hymenium is adnate or adnexed | |

| stipe has a ring | |

| spore print is purple | |

| ecology is saprotrophic | |

| edibility: psychoactive | |

Taxonomy and naming

The species was first described in 1906 as Stropharia cubensis by Franklin Sumner Earle in Cuba.[1] In 1907 it was identified as Naematoloma caerulescens in Tonkin by Narcisse Théophile Patouillard,[2] while in 1941 it was called Stropharia cyanescens by William Alphonso Murrill in Florida.[3] These synonyms were later assigned to the species Psilocybe cubensis.[4][5]

The name Psilocybe is derived from the Greek roots psilos (ψιλος) and kubê (κυβη),[6] and translates as "bare head". Cubensis means "coming from Cuba", and refers to the type locality published by Earle.

Description

- Pileus: 2–8 cm (1–3 in), conic to convex, becoming broadly convex to plane in age, may retain a slight umbo, margin even, reddish-cinnamon brown when young becoming golden brown in age, viscid when moist, hygrophanous, glabrous, sometimes with white universal veil remnants decorating the cap, more or less smooth. Flesh whitish, bruising blue in age or where injured.

- Gills: adnate to adnexed to sometimes seceding attachment, close, narrow to slightly wider towards the center, at first pallid to gray, becoming dark purplish to blackish in age, somewhat mottled, edges remaining whitish.

- Spore print: dark purple brown

- Stipe: 4–15 cm (2–6 in) long, 0.5–3.8 cm (0.2–1.5 in) thick, white to yellowish in age, hollow or somewhat stuffed, the well developed veil leaves a persistent white membranous annulus whose surface usually becomes concolorous with the gills because of falling spores, bruising blue or bluish-green when injured.

- Taste: farinaceous

- Odor: farinaceous

- Microscopic features: spores 11.5–17 x 8–11 µm, subellipsoid, basidia 4-spored but sometimes 2- or 3-, pleurocystidia and cheilocystidia present.[7]

Psychedelic and entheogenic use

Psilocybe cubensis is probably the most widely known of the psilocybin-containing mushrooms used for triggering psychedelic experiences after ingestion. Its major psychoactive compounds are:

- Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine)

- Psilocin (4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine)

- Baeocystin (4-phosphoryloxy-N-methyltryptamine)

- Norbaeocystin (4-phosphoryloxytryptamine)

The concentrations of psilocin and psilocybin, as determined by high-performance liquid chromatography, are in the range of 0.14–0.42% and 0.37–1.30% (dry weight) in the whole mushroom, 0.17–0.78% and 0.44–1.35% in the cap, and 0.09 and 0.30%/0.05–1.27% in the stem, respectively.[8]

Individual brain chemistry and psychological predisposition play a significant role in determining appropriate doses. For a modest psychedelic effect, a minimum of one gram of dried Psilocybe cubensis mushrooms is ingested orally, 0.25–1 gram is usually sufficient to produce a mild effect, 1–2.5 grams usually provides a moderate effect, and 2.5 grams and higher usually produces strong effects.[9] For most people, 3.5 dried grams (1/8 oz) would be considered a high dose and may produce an intense experience; this is, however, typically considered a standard dose among recreational users. For many individuals, doses above three grams may be overwhelming. For a few rare people, doses as small as 0.25 gram can produce full-blown effects normally associated with very high doses. For most people, however, that dose level would result in virtually no effects. Due to factors such as age and storage method, the psilocybin content of a given sample of mushrooms will vary. Effects usually start after approximately 20–60 minutes (depending on method of ingestion and stomach contents) and may last from four to ten hours, depending on dosage. Visual distortions often occur, including walls that seem to breathe, a vivid enhancement of colors and the animation of organic shapes.

The effects of very high doses can be overwhelming depending on the particular phenotype of cubensis, grow method, and the individual. It is recommended not to eat wild mushrooms as they may be poisonous.[10]

Legality

Psilocybin and psilocin are listed as Schedule I drugs under the United Nations 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[11] However, mushrooms containing psilocybin and psilocin are not illegal in some parts of the world. For example, in Brazil they are legal, but extractions from the mushroom containing psilocybin and psilocin remain illegal. In the United States, Psilocybe cubensis is illegal in all states. However, as of May 8, 2019 Denver, Colorado has decriminalized it for those 21 and up. On June 4, 2019, Oakland, California followed suit, decriminalizing psilocybin containing mushrooms as well as the Peyote cactus. On January 29, 2020, Santa Cruz, California decriminalized naturally-occurring psychedelics, including psilocybin mushrooms.[12]

Cultivation

Personal-scale cultivation of Psilocybe cubensis mushrooms ranges from the relatively simple and small-scale PF Tek and other "cake" methods, that produce a limited amount of mushrooms, to advanced techniques utilizing methods of professional mushroom cultivators. These advanced methods require a greater investment of time, money, and knowledge, but reward the diligent cultivator with far larger and much more consistent harvests.

Terence and Dennis McKenna made Psilocybe cubensis particularly famous when they published Psilocybin: The Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide in the 1970s upon their return from the Amazon rainforest, having deduced new methods (based on pre-existing techniques originally described by J.P. San Antonio[13]) for growing psilocybin mushrooms and assuring their audience that Psilocybe cubensis were amongst the easiest psilocybin-containing mushrooms to cultivate.[14]

Potency of cultivated specimens can vary widely in accordance with each flush (harvest). In a classic paper published by Jeremy Bigwood and M.W. Beug, it was shown that with each flush, psilocybin levels varied somewhat unpredictably but were much the same on the first flush as they were on the last flush; however, psilocin was typically absent in the first two flushes but peaked by the fourth flush, making it the most potent. Two strains were also analyzed to determine potency in caps and stems: In one strain the caps contained generally twice as much psilocybin as the stems, but the small amount of psilocin present was entirely in the stems. In the other strain, a trace of psilocin was present in the cap but not in the stem; the cap and stem contained equal amounts of psilocybin. The study concluded that the levels of psilocybin and psilocin vary by over a factor of four in cultures of Psilocybe cubensis grown under controlled conditions.[15]

Relationship with cattle

With cow dung being the preferred habitat of Psilocybe cubensis, its circumtropical distribution is largely encouraged, if not caused, by the worldwide cattle ranching industry.[16]

Because Psilocybe cubensis is intimately associated with cattle ranching, the fungus has found unique dispersal niches not available to most other members of the family Strophariaceae. Of particular interest is the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis), a colonizer of Old World origin (via S. America), whose range of distribution overlaps much of that of Psilocybe cubensis. Cattle egrets typically walk alongside cattle, preying on insects; they track through spore-laden vegetation and cow dung, and transfer the spores to suitable habitat, often thousands of miles away during migration activities. This type of spore dispersal is known as zoochory, and it enables a parent species to propagate over a much greater range than it could achieve alone. The relationship between cattle, cattle egrets, and Psilocybe cubensis is an example of symbiosis—a situation in which dissimilar organisms live together in close association.[17]

See also

- List of psilocybin mushrooms

- Psilocybin mushrooms

- Botanical identity of soma-haoma

References

- Earle FS (1906). "Algunos hongos cubanos". Información Anual Estación Central Agronomica Cuba (in Spanish). 1: 225–42 (p.240–241).

- Patouillard NT (1907). "Champignons nouveaux du Tonkin". Bulletin de la Société Mycologique de France (in French). 23 (1).

- Murrill, W.A. (May–June 1941). "Some Florida Novelties". Mycologia. 33 (3): 279–287. doi:10.2307/3754763. JSTOR 3754763.

- "Naematoloma caerulescens Pat. 1907". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- "Stropharia cyanescens Murrill 1941". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- Cornelis, Schrevel (1826). Schrevelius' Greek lexicon, tr. into Engl. with numerous corrections. p. 358. Retrieved 2011-10-04.

- Stamets, Paul (1996). Psilocybin Mushrooms of the World. Ten Speed Press. pp. g. 108. ISBN 0-89815-839-7.

- Tsujikawa, K.; Kanamori, T.; Iwata, Y.; Ohmae, Y.; Sugita, R.; Inoue, H.; Kishi, T. (December 2003). "Morphological and chemical analysis of magic mushrooms in Japan" (PDF). Forensic Science International. 138 (1–3): 85–90. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2003.08.009. PMID 14642723.

- Erowid (2006). "Erowid Psilocybin Mushroom Vault: Dosage" (shtml). Erowid. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- Phillips, Roger (2010). Mushrooms and Other Fungi of North America. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-55407-651-2.

- "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. August 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2005. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- "Breaking: Santa Cruz City Council Votes to Decriminalize Entheogenic Plants and Fungi". DoubleBlind Magazine. 2020-01-29. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- San Antonio, J.P. "A Laboratory Method to Obtain Fruit from Cased Grain Spawn of the Cultivated Mushroom Agaricus bisporus". Mycologia 63: 16-21 (1971).

- "Terence McKenna's books in print". Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- Bigwood, J. and M.W. Beug. "Variation of psilocybin and psilocin levels in repeated flushes (harvests) of mature sporocarps of Psilocybe cubensis (Earle) Singer." Journal of Ethnopharmacology 5(3): 287-291 (1982).

- http://www.psilosophy.info/resources/Psilocybin.magic.mushroom.growers.guide.pdf

- Smith, D. "The cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis): colonizer of Old World origin and a vector of Psilocybe cubensis spores." Stain Blue Press, Spring, Texas (1996). http://www.stainblue.com/cubensis.html

Further reading

- Guzman, G. The Genus Psilocybe: A Systematic Revision of the Known Species Including the History, Distribution and Chemistry of the Hallucinogenic Species. Beihefte zur Nova Hedwigia Heft 74. J. Cramer, Vaduz, Germany (1983) [now out of print].

- Guzman, G. "Supplement to the genus Psilocybe." Bibliotheca Mycologica 159: 91-141 (1995).

- Haze, Virginia & Dr, K. Mandrake, PhD. The Psilocybin Mushroom Bible: The Definitive Guide to Growing and Using Magic Mushrooms. Green Candy Press: Toronto, Canada, 2016. ISBN 978-1937866-28-0. www.greencandypress.com.

- Nicholas, L.G.; Ogame, Kerry (2006). Psilocybin Mushroom Handbook: Easy Indoor and Outdoor Cultivation. Quick American Archives. ISBN 0-932551-71-8.

- Oss, O.T.; O.N. Oeric (1976). Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide. Quick American Publishing Company. ISBN 0-932551-06-8.

- Stamets, Paul; Chilton, J.S. (1983). Mushroom Cultivator, The. Olympia: Agarikon Press. ISBN 0-9610798-0-0.

- Stamets, Paul (1996). Psilocybin Mushrooms of the World. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 0-9610798-0-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Psilocybe cubensis. |

- The Ones That Stain Blue Studies in ethnomycology including the contributions of Maria Sabina, Dr. Albert Hofmann and Dr. Gaston Guzman.

- Erowid Psilocybin Mushroom Vault

- Mushroom John's Tale of the Shrooms: Psilocybe cubensis (200 photographs and Description

- Stamets, Paul (1983). The Mushroom Cultivator. Olympia, Washington, 98507, USA: Agarikon Press. ISBN 0-96 1 0798-0-0.CS1 maint: location (link)