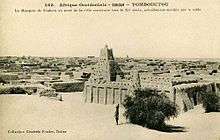

Sankore Madrasah

Sankoré Madrasah (also called the University of Sankoré, or Sankore Masjid) is one of three ancient centers of learning located in Timbuktu, Mali. The three mosques of Sankoré, Djinguereber and Sidi Yahya compose the University of Timbuktu. Madrasah (مدرسة) means school/university in Arabic and also in other languages that have been influenced by Islam.

History

The University of Sankore has its roots in the Sankore Mosque which was founded in 989 AD by Al-Qadi Aqib ibn Mahmud ibn Umar, the Supreme Judge of Timbuktu. The Sankore University prospered and became a very significant seat of learning in the Muslim world, especially under the reign of Mansa Musa (1307–1332) and the Askia Dynasty (1493–1591).[1]

Growth as a center of learning

Timbuktu had long been a destination or stop for merchants from the Middle East and North Africa. It wasn't long before ideas as well as merchandise began passing through the fabled city. Since most if not all these traders were Muslim, the mosque would see visitors constantly. The temple accumulated a wealth of books from throughout the Muslim world becoming not only a center of worship but a center of learning. Books became more valuable than any other commodity in the city, and private libraries sprouted up in the homes of local scholars.

Apex

By the end of Mansa Musa's reign (early 14th century CE), the Sankoré Masjid had been converted into a fully staffed Madrassa (Islamic school or in this case university) with the largest collections of books in Africa since the Library of Alexandria. The level of learning at Timbuktu's Sankoré University was superior to that of many other Islamic centers in the world. The Sankoré Masjid was capable of housing 25,000 students and had one of the largest libraries in the world with between 400,000 and 700,000 manuscripts.[2]

Organization

As the center of an Islamic scholarly community, the University was very different in organization from the universities of medieval Europe. It had no central administration other than the Emperor. It had no student registers but kept copies of its students' publishing. It was composed of several entirely independent schools or colleges, each run by a single master or imam. Students associated themselves with a single teacher, and courses took place in the open courtyard of the mosque or at private residences.

Curriculum

The curriculum of Sankoré and other masjids in the area had four levels of schooling or "degrees". On graduating from each level, students would receive a turban symbolizing their mastery. The schooling was not secular as arguments that could not be backed by the Qur'an were inadmissible in debates. However, secular teaching (geometry, mathematics) were included and stressed to develop well-rounded individuals.

Qur'anic School

The first or primary degree (Qur'anic school) required a mastery of Arabic and certain African languages and writing along with complete memorization of the Qur'an. Students were also introduced to basic sciences at this level.

General Studies

The secondary degree or General Studies degree focused on full immersion in the basic sciences. Students learned grammar, mathematics, geography, history, physics, astronomy, chemistry alongside more advanced learnings of the Qur'an. At this level they learned Hadiths, jurisprudence and the sciences of spiritual purification according to Islam. Finally, they began an introduction to trade school and business ethics. On graduation day, students were given turbans symbolizing Divine light, wisdom, knowledge and excellent moral conduct. After receiving their diplomas the students would gather outside the examination building or the main campus library and throw their turbans high into the air cheering and holding each other's hands to show that they were all brothers and sisters.[3]

Superior Degree

The Superior degree required students to study under specialized professors doing research work. Much of the learning centered on debates to philosophic or religious questions. Before graduating from this level, students attached themselves to a Sheik (Islamic teacher) and demonstrated a strong character.

Alumni Level

The last level of learning at Sankoré or any of the Masjids was the level of Judge or Professor. These men worked mainly as judges for the city and eventually the region dispersing learned men to all the principal cities in Mali. A third level student who had impressed his Sheik enough was admitted into a "circle of knowledge" and valued as a truly learned individual and expert in his field. The members of this scholar's club were the equivalent of tenured professors. Those who did not leave Timbuktu remained there to teach or counsel the leading people of the region on important legal and religious matters. They would receive questions from the region's powerful (kings or governors) and distribute them to the third level students as research assignments. After discussing the findings among themselves, the scholars would issue a fatwa on the best way to deal with the problem at hand.

Scholars of Sankoré

Scholars wrote their own books as part of a socioeconomic model. Students were charged with copying these books and any other books they could get their hands on. Today there are over 700,000 manuscripts in Timbuktu with many dating back to West Africa's Golden Age (12th to 16th centuries).[4]

- Ahmed Baba

- Mohammed Bagayogo

- Modibo Mohammed Al Kaburi

See also

- Ancient university

- List of oldest universities in continuous operation

- Medieval university

- Songhai Empire

- Timbuktu Manuscripts Project

References

- Woods, Michael (2009). Seven Wonders of Ancient Africa. London: Lerner. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7613-4320-2.

- See Hamdun, Said; King, Noël, eds. (1975). Ibn Battuta in Black Africa. London: Rex Collins. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-901720-57-7.

- See Cissoko, Sékéné Mody (1969). "L'intelligentsia de Tombouctou aux 15e et 16e siècles". Présence Africaine. 72: 48–72, and Triaud, Jean-Louis (1973). Islam et sociétés soudanaises au Moyen-Âge: Étude historique. Étdues voltaïques. vol. 16. Paris – Adidjan – Niamey. pp. 167 sq.

- Olajide, Olayanju (2013). The Complete Concise History of the Slave Trade. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4817-8159-6.

Further reading

- Saad, Elias N. (1983). Social History of Timbuktu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables 1400–1900. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24603-2.

External links

- Ancient Manuscripts from the Desert Libraries of Timbuktu, Library of Congress — exhibition of manuscripts from the Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library