Little Ice Age

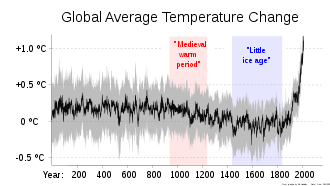

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of cooling that occurred after the Medieval Warm Period.[2] Although it was not a true ice age, the term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939.[3] It has been conventionally defined as a period extending from the 16th to the 19th centuries,[4][5][6] but some experts prefer an alternative timespan from about 1300[7] to about 1850.[8][9][10]

The NASA Earth Observatory notes three particularly cold intervals: one beginning about 1650, another about 1770, and the last in 1850, all separated by intervals of slight warming.[6] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Third Assessment Report considered the timing and areas affected by the Little Ice Age suggested largely independent regional climate changes rather than a globally synchronous increased glaciation. At most, there was modest cooling of the Northern Hemisphere during the period.[11]

Several causes have been proposed: cyclical lows in solar radiation, heightened volcanic activity, changes in the ocean circulation, variations in Earth's orbit and axial tilt (orbital forcing), inherent variability in global climate, and decreases in the human population (for example from the Black Death and the colonization of the Americas).[12]

Areas involved

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Third Assessment Report (TAR) of 2001 described the areas affected:

Evidence from mountain glaciers does suggest increased glaciation in a number of widely spread regions outside Europe prior to the twentieth century, including Alaska, New Zealand and Patagonia. However, the timing of maximum glacial advances in these regions differs considerably, suggesting that they may represent largely independent regional climate changes, not a globally-synchronous increased glaciation. Thus current evidence does not support globally synchronous periods of anomalous cold or warmth over this interval, and the conventional terms of "Little Ice Age" and "Medieval Warm Period" appear to have limited utility in describing trends in hemispheric or global mean temperature changes in past centuries.... [Viewed] hemispherically, the "Little Ice Age" can only be considered as a modest cooling of the Northern Hemisphere during this period of less than 1°C relative to late twentieth century levels.[11]

The IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) of 2007 discusses more recent research, giving particular attention to the Medieval Warm Period.

when viewed together, the currently available reconstructions indicate generally greater variability in centennial time scale trends over the last 1 kyr than was apparent in the TAR.... The result is a picture of relatively cool conditions in the seventeenth and early nineteenth centuries and warmth in the eleventh and early fifteenth centuries, but the warmest conditions are apparent in the twentieth century. Given that the confidence levels surrounding all of the reconstructions are wide, virtually all reconstructions are effectively encompassed within the uncertainty previously indicated in the TAR. The major differences between the various proxy reconstructions relate to the magnitude of past cool excursions, principally during the twelfth to fourteenth, seventeenth and nineteenth centuries.[13]

Dating

There is no consensus regarding the time when the Little Ice Age began,[14][15] but a series of events before the known climatic minima has often been referenced. In the 13th century, pack ice began advancing southwards in the North Atlantic, as did glaciers in Greenland. Anecdotal evidence suggests expanding glaciers almost worldwide. Based on radiocarbon dating of roughly 150 samples of dead plant material with roots intact, collected from beneath ice caps on Baffin Island and Iceland, Miller et al. (2012)[7] state that cold summers and ice growth began abruptly between 1275 and 1300, followed by "a substantial intensification" from 1430 to 1455.[7]

In contrast, a climate reconstruction based on glacial length[16][17] shows no great variation from 1600 to 1850 but strong retreat thereafter.

Therefore, any of several dates ranging over 400 years may indicate the beginning of the Little Ice Age:

- 1250 for when Atlantic pack ice began to grow; cold period possibly triggered or enhanced by the massive eruption of Samalas volcano in 1257[18]

- 1275 to 1300 based on the radiocarbon dating of plants killed by glaciation

- 1300 for when warm summers stopped being dependable in Northern Europe

- 1315 for the rains and Great Famine of 1315–1317

- 1550 for theorized beginning of worldwide glacial expansion

- 1650 for the first climatic minimum.

The Little Ice Age ended in the latter half of the 19th century or early in the 20th century.[19][20][21]

Geophysical and social impact by region

Europe

The Baltic Sea froze over twice, 1303 and 1306-07; years followed of "unseasonable cold, storms and rains, and a rise in the level of the Caspian Sea.”[22] The Little Ice Age brought colder winters to parts of Europe and North America. Farms and villages in the Swiss Alps were destroyed by encroaching glaciers during the mid-17th century.[23] Canals and rivers in Great Britain and the Netherlands were frequently frozen deeply enough to support ice skating and winter festivals.[23] The first River Thames frost fair was in 1608 and the last in 1814; changes to the bridges and the addition of the Thames Embankment affected the river flow and depth, greatly diminishing the possibility of further freezes. Freezing of the Golden Horn and the southern section of the Bosphorus took place in 1622. In 1658, a Swedish army marched across the Great Belt to Denmark to attack Copenhagen. The winter of 1794–1795 was particularly harsh: the French invasion army under Pichegru was able to march on the frozen rivers of the Netherlands, and the Dutch fleet was locked in the ice in Den Helder harbour.

Sea ice surrounding Iceland extended for miles in every direction, closing harbors to shipping. The population of Iceland fell by half, but that may have been caused by skeletal fluorosis after the eruption of Laki in 1783.[24] Iceland also suffered failures of cereal crops and people moved away from a grain-based diet.[25] The Norse colonies in Greenland starved and vanished by the early 15th century, as crops failed and livestock could not be maintained through increasingly harsh winters. Greenland was largely cut off by ice from 1410 to the 1720s.[26]

In his 1995 book the early climatologist Hubert Lamb said that in many years, "snowfall was much heavier than recorded before or since, and the snow lay on the ground for many months longer than it does today."[27] In Lisbon, Portugal, snowstorms were much more frequent than today; one winter in the 17th century produced eight snowstorms.[28] Many springs and summers were cold and wet but with great variability between years and groups of years. Crop practices throughout Europe had to be altered to adapt to the shortened, less reliable growing season, and there were many years of dearth and famine (such as the Great Famine of 1315–1317, but that may have been before the Little Ice Age).[29] According to Elizabeth Ewan and Janay Nugent, "Famines in France 1693–94, Norway 1695–96 and Sweden 1696–97 claimed roughly 10 percent of the population of each country. In Estonia and Finland in 1696–97, losses have been estimated at a fifth and a third of the national populations, respectively."[30] Viticulture disappeared from some northern regions and storms caused serious flooding and loss of life. Some of them resulted in permanent loss of large areas of land from the Danish, German, and Dutch coasts.[27]

The violin maker Antonio Stradivari produced his instruments during the Little Ice Age. The colder climate is proposed to have caused the wood used in his violins to be denser than in warmer periods, contributing to the tone of his instruments.[31] According to the science historian James Burke, the period inspired such novelties in everyday life as the widespread use of buttons and button-holes, and knitting of custom-made undergarments to better cover and insulate the body. Chimneys were invented to replace open fires in the centre of communal halls, so allowing houses with multiple rooms, separation of masters from servants and thus the development of social classes.[32]

The Little Ice Age, by anthropologist Brian Fagan of the University of California at Santa Barbara, tells of the plight of European peasants during the 1300 to 1850 chill: famines, hypothermia, bread riots and the rise of despotic leaders brutalizing an increasingly dispirited peasantry. In the late 17th century, agriculture had dropped off dramatically: "Alpine villagers lived on bread made from ground nutshells mixed with barley and oat flour." [33] Historian Wolfgang Behringer has linked intensive witch-hunting episodes in Europe to agricultural failures during the Little Ice Age.[34]

The Frigid Golden Age, by environmental historian Dagomar Degroot of Georgetown University, by contrast, reveals that some societies thrived while others faltered during the Little Ice Age. In particular, the Little Ice Age transformed environments around the Dutch Republic — the precursor to the present-day Netherlands — so that they were easier to exploit in commerce and conflict. The Dutch were resilient, even adaptive, in the face of weather that devastated neighboring countries. Merchants exploited harvest failures, military commanders took advantage of shifting wind patterns, and inventors developed technologies that helped them profit from the cold. The 17th-century "Golden Age" of the Republic therefore owed much to the flexibility of the Dutch in coping with a changing climate.[35]

Cultural responses

Historians have argued that cultural responses to the consequences of the Little Ice Age in Europe consisted of violent scapegoating.[36][37][38][34][39] The prolonged cold, dry periods brought drought upon many European communities, resulting in poor crop growth, poor livestock survival, and increased activity of pathogens and disease vectors.[40] Disease tends to intensify under the same conditions that unemployment and economic difficulties arise: prolonged, cold, dry seasons. Both of these outcomes – disease and unemployment – enhance each other, generating a lethal positive feedback loop.[40] Although these communities had some contingency plans, such as better crop mixes, emergency grain stocks, and international food trade, these did not always prove effective.[36] Communities often lashed out via violent crimes, including robbery and murder; sexual offense accusations increased as well, such as adultery, bestiality, and rape.[37] Europeans sought explanations for the famine, disease, and social unrest that they were experiencing, and blamed the innocent. Evidence from several studies indicate that increases in violent actions against marginalized groups that were held responsible for the Little Ice Age overlap with years of particularly cold, dry weather.[38][34][36]

One example of the violent scapegoating occurring during the Little Ice Age was the resurgence of witchcraft trials, as argued by Oster (2004) and Behringer (1999). Oster and Behringer argue that this resurgence was brought upon by the climatic decline. Prior to the Little Ice Age, "witchcraft" was considered an insignificant crime and victims were rarely accused.[34] But beginning in the 1380s, just as the Little Ice Age began, European populations began to link magic and weather-making.[34] The first systematic witch hunts began in the 1430s, and by the 1480s it was widely believed that witches should be held accountable for poor weather.[34] Witches were blamed for direct and indirect consequences of the Little Ice Age: livestock epidemics, cows that gave too little milk, late frosts, and unknown diseases.[37] In general, as the temperature dropped, the number of witchcraft trials rose, and trials decreased when temperature increased.[36][34] The peaks of witchcraft persecutions overlap with hunger crises that occurred in 1570 and 1580, the latter lasting a decade.[34] These trials primarily targeted poor women, many of whom were widows. Not everybody agreed that witches should be persecuted for weather-making, but such arguments primarily focused not upon whether witches existed, but upon whether witches had the capability to control the weather.[34][36] The Catholic Church in the Early Middle Ages argued that witches could not control the weather because they were mortals, not God, but by the mid-13th-century most populations agreed with the idea that witches could control natural forces.[36]

Historians have argued that Jewish populations were also blamed for climatic deterioration during the Little Ice Age.[37][39] Christianity was the official religion of Western Europe, and within these populations there was a great degree of anti-Semitism.[37] There was no direct link made between Jews and weather conditions, they were only blamed for indirect consequences such as disease.[37] For example, outbreaks of the plague were often blamed on Jews; in Western European cities during the 1300s Jewish populations were murdered in an attempt to stop the spread of the plague.[37] Rumors were spread that either Jews were poisoning wells themselves, or conspiring against Christians by telling those with leprosy to poison the wells.[37] As a response to such violent scapegoating, Jewish communities sometimes converted to Christianity or migrated to the Ottoman Empire, Italy, or to territories of the Holy Roman Empire.[37]

In addition to blaming marginalized groups and individuals, some populations blamed the cold periods and the resulting famine and disease during the Little Ice Age on general divine displeasure.[38] Oppressed groups, however, took the brunt of the burden in attempts to cure it.[38] For example, in Germany, regulations were imposed upon activities such as gambling and drinking, which disproportionately affected the lower class, and women were forbidden from showing their knees.[38] Other regulations affected the wider population, such as prohibiting dancing and sexual activities, as well as moderating food and drink intake.[38]

In Ireland, Catholics blamed the Reformation for the bad weather. The Annals of Loch Cé, in its entry for the year 1588, describes a midsummer snowstorm: "a wild apple was not larger than each stone of it," blaming it on the presence of a "wicked, heretical, bishop in Oilfinn"; that is, the Protestant Bishop of Elphin, John Lynch.[41][42]

Depictions of winter in European painting

William James Burroughs analyses the depiction of winter in paintings, as does Hans Neuberger.[43] Burroughs asserts that it occurred almost entirely from 1565 to 1665 and was associated with the climatic decline from 1550 onwards. Burroughs claims that there had been almost no depictions of winter in art, and he "hypothesizes that the unusually harsh winter of 1565 inspired great artists to depict highly original images and that the decline in such paintings was a combination of the 'theme' having been fully explored and mild winters interrupting the flow of painting".[44] Wintry scenes, which entail technical difficulties in painting, have been regularly and well handled since the early 15th century by artists in illuminated manuscript cycles showing the Labours of the Months, typically placed on the calendar pages of books of hours. January and February are typically shown as snowy, as in February in the famous cycle in the Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, painted 1412–1416 and illustrated below. Since landscape painting had not yet developed as an independent genre in art, the absence of other winter scenes is not remarkable. On the other hand, snowy winter landscapes and stormy seascapes in particular became artistic genres in the Dutch Republic during the coldest and stormiest decades of the Little Ice Age. At the time when the Little Ice Age was at its height, Dutch observations and reconstructions of similar weather in the past caused artists consciously paint local manifestations of a cooler, stormier climate. This was a break from European conventions as Dutch paintings and realistic landscapes depicted scenes from everyday life, which most modern scholars believe that were full of symbolic messages and metaphors that would have been clear to contemporary customers.[45]

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

The famous winter landscape paintings by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, such as The Hunters in the Snow, are all thought to have been painted in 1565. His son Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564–1638) also painted many snowy landscapes, but according to Burroughs, he "slavishly copied his father's designs. The derivative nature of so much of this work makes it difficult to draw any definite conclusions about the influence of the winters between 1570 and 1600...".[44][46]

Burroughs says that snowy subjects return to Dutch Golden Age painting with works by Hendrick Avercamp from 1609 onwards. There is then a hiatus between 1627 and 1640, before the main period of such subjects from the 1640s to the 1660s, which relates well with climate records for the later period. The subjects are less popular after about 1660, but that does not match any recorded reduction in severity of winters and may reflect only changes in taste or fashion. In the later period between the 1780s and 1810s, snowy subjects again became popular.[44]

Neuberger analysed 12,000 paintings, held in American and European museums and dated between 1400 and 1967, for cloudiness and darkness.[43] His 1970 publication shows an increase in such depictions that corresponds to the Little Ice Age,[43] peaking between 1600 and 1649.[47]

Paintings and contemporary records in Scotland demonstrate that curling and ice skating were popular outdoor winter sports, with curling dating back to the 16th century and becoming widely popular in the mid-19th century.[48] As an example, an outdoor curling pond constructed in Gourock in the 1860s remained in use for almost a century, but increasing use of indoor facilities, problems of vandalism, and milder winters led to the pond being abandoned in 1963.[49]

North America

Early European explorers and settlers of North America reported exceptionally severe winters. For example, according to Lamb, Samuel Champlain reported bearing ice along the shores of Lake Superior in June 1608. Both Europeans and indigenous peoples suffered excess mortality in Maine during the winter of 1607–1608, and extreme frost was reported in the Jamestown, Virginia, settlement at the same time.[27] Native Americans formed leagues in response to food shortages.[26] The journal of Pierre de Troyes, Chevalier de Troyes, who led an expedition to James Bay in 1686, recorded that the bay was still littered with so much floating ice that he could hide behind it in his canoe on 1 July.[50] In the winter of 1780, New York Harbor froze, allowing people to walk from Manhattan Island to Staten Island.

The extent of mountain glaciers had been mapped by the late 19th century. In the north and the south temperate zones, Equilibrium Line Altitude (the boundaries separating zones of net accumulation from those of net ablation) were about 100 metres (330 ft) lower than they were in 1975.[51] In Glacier National Park, the last episode of glacier advance came in the late 18th and the early 19th centuries.[52] In 1879, John Muir found that Glacier Bay ice had retreated 48 miles.[53] In Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, large temperature excursions were possibly related to changes in the strength of North Atlantic thermohaline circulation.[54]

Mesoamerica

An analysis of several climate proxies undertaken in Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula, linked by its authors to Maya and Aztec chronicles relating periods of cold and drought, supports the existence of the Little Ice Age in the region.[55]

Atlantic Ocean

In the North Atlantic, sediments accumulated since the end of the last ice age, nearly 12,000 years ago, show regular increases in the amount of coarse sediment grains deposited from icebergs melting in the now open ocean, indicating a series of 1–2 °C (2–4 °F) cooling events recurring every 1,500 years or so.[56] The most recent of these cooling events was the Little Ice Age. These same cooling events are detected in sediments accumulating off Africa, but the cooling events appear to be larger, ranging between 3–8 °C (6–14 °F).[57]

Asia

Although the original designation of a Little Ice Age referred to reduced temperature of Europe and North America, there is some evidence of extended periods of cooling outside this region, but it is not clear whether they are related or independent events. Mann states:[4]

While there is evidence that many other regions outside Europe exhibited periods of cooler conditions, expanded glaciation, and significantly altered climate conditions, the timing and nature of these variations are highly variable from region to region, and the notion of the Little Ice Age as a globally synchronous cold period has all but been dismissed.

In China, warm-weather crops such as oranges were abandoned in Jiangxi Province, where they had been grown for centuries.[58] Also, the two periods of most frequent typhoon strikes in Guangdong coincide with two of the coldest and driest periods in northern and central China (1660–1680, 1850–1880).[59] Scholars have argued that the fall of the Ming dynasty may have been partially caused by the droughts and famines caused by the Little Ice Age.[60]

In Pakistan, the Balochistan province became colder and the native Baloch people started mass migration and settled along the Indus River in Sindh and Punjab provinces.[61]

Africa

In Ethiopia and North Africa, permanent snow was reported on mountain peaks at levels where it does not occur today.[58] Timbuktu, an important city on the trans-Saharan caravan route, was flooded at least 13 times by the Niger River; there are no records of similar flooding before or since.[58]

In Southern Africa, sediment cores retrieved from Lake Malawi show colder conditions between 1570 and 1820, suggesting the Lake Malawi records "further support, and extend, the global expanse of the Little Ice Age."[62] A novel 3,000-year temperature reconstruction method, based on the rate of stalagmite growth in a cold cave in South Africa, further suggests a cold period from 1500 to 1800 "characterizing the South African Little Ice age."[63] Periglacial features in the eastern Lesotho Highlands might have been reactivated by the Little Ice Age.[64]

Antarctica

2 mixing ratios at Law Dome

Kreutz et al. (1997) compared results from studies of West Antarctic ice cores with the Greenland Ice Sheet Project Two GISP2 and suggested a synchronous global cooling.[65] An ocean sediment core from the eastern Bransfield Basin in the Antarctic Peninsula shows centennial events that the authors link to the Little Ice Age and Medieval Warm Period.[66] The authors note "other unexplained climatic events comparable in duration and amplitude to the LIA and MWP events also appear."

The Siple Dome (SD) had a climate event with an onset time that is coincident with that of the Little Ice Age in the North Atlantic based on a correlation with the GISP2 record. The event is the most dramatic climate event in the SD Holocene glaciochemical record.[67] The Siple Dome ice core also contained its highest rate of melt layers (up to 8%) between 1550 and 1700, most likely because of warm summers.[68] Law Dome ice cores show lower levels of CO

2 mixing ratios from 1550 to 1800, which Etheridge and Steele conjecture are "probably as a result of colder global climate."[69]

Sediment cores in Bransfield Basin, Antarctic Peninsula, have neoglacial indicators by diatom and sea-ice taxa variations during the Little Ice Age.[70] Stable isotope records from the Mount Erebus Saddle ice core site suggests that the Ross Sea region experienced 1.6 ± 1.4 °C cooler average temperatures during the Little Ice Age, compared to the last 150 years.[71]

Australia and New Zealand

Limited evidence describes conditions in Australia. Lake records in Victoria suggest that conditions, at least in the south of the state, were wet and/or unusually cool. In the north, evidence suggests fairly dry conditions, but coral cores from the Great Barrier Reef show similar rainfall as today but with less variability. A study that analyzed isotopes in Great Barrier Reef corals suggested that increased water vapor transport from southern tropical oceans to the poles contributed to the Little Ice Age.[19] Borehole reconstructions from Australia suggest that over the last 500 years, the 17th century was the coldest on the continent, but the borehole temperature reconstruction method does not show good agreement between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.[72]

On the west coast of the Southern Alps of New Zealand, the Franz Josef glacier advanced rapidly during the Little Ice Age and reached its maximum extent in the early 18th century, in one of the few cases of a glacier thrusting into a rainforest.[33] Based on dating of a yellow-green lichen of the Rhizocarpon subgenus, the Mueller Glacier, on the eastern flank of the Southern Alps within Aoraki / Mount Cook National Park, is considered to have been at its maximum extent between 1725 and 1730.[73]

Pacific Islands

Sea-level data for the Pacific Islands suggest that sea level in the region fell, possibly in two stages, between 1270 and 1475. This was associated with a 1.5 °C fall in temperature (determined from oxygen-isotope analysis) and an observed increase in El Niño frequency.[74] Tropical Pacific coral records indicate the most frequent, intense El Niño-Southern Oscillation activity in the mid-seventeenth century.[75]

South America

Tree-ring data from Patagonia show cold episodes between 1270 and 1380 and from 1520 to 1670, contemporary with the events in the Northern Hemisphere.[76][77] Eight sediment cores taken from Puyehue Lake have been interpreted as showing a humid period from 1470 to 1700, which the authors describe as a regional marker of the onset of the Little Ice Age.[78] A 2009 paper details cooler and wetter conditions in southeastern South America between 1550 and 1800, citing evidence obtained via several proxies and models.[79] 18O records from three Andean ice cores show a cool period from 1600–1800.[80]

Although only anecdotal evidence, in 1675 the Spanish Antonio de Vea expedition entered San Rafael Lagoon through Río Témpanos (Spanish for "Ice Floe River") without mentioning any ice floe but stating that the San Rafael Glacier did not reach far into the lagoon. In 1766, another expedition noticed that the glacier reached the lagoon and calved into large icebergs. Hans Steffen visited the area in 1898, noticing that the glacier penetrated far into the lagoon. Such historical records indicate a general cooling in the area between 1675 and 1898: "The recognition of the LIA in northern Patagonia, through the use of documentary sources, provides important, independent evidence for the occurrence of this phenomenon in the region."[81] As of 2001, the border of the glacier had significantly retreated as compared to the borders of 1675.[81]

Possible causes

Scientists have tentatively identified seven possible causes of the Little Ice Age: orbital cycles; decreased solar activity; increased volcanic activity; altered ocean current flows;[82] fluctuations in the human population in different parts of the world causing reforestation, or deforestation; and the inherent variability of global climate.

Orbital cycles

Orbital forcing from cycles in the earth's orbit around the sun has, for the past 2,000 years, caused a long-term northern hemisphere cooling trend that continued through the Middle Ages and the Little Ice Age. The rate of Arctic cooling is roughly 0.02 °C per century.[83] This trend could be extrapolated to continue into the future, possibly leading to a full ice age, but the twentieth-century instrumental temperature record shows a sudden reversal of this trend, with a rise in global temperatures attributed to greenhouse gas emissions.[83]

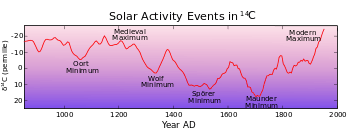

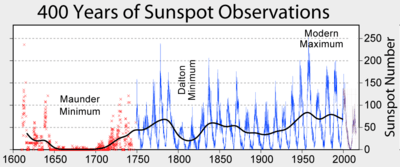

Solar activity

There is still a very poor understanding of the correlation between low sunspot activity and cooling temperatures.[84][85] During the period 1645–1715, in the middle of the Little Ice Age, there was a period of low solar activity known as the Maunder Minimum. The Spörer Minimum has also been identified with a significant cooling period between 1460 and 1550.[86] Other indicators of low solar activity during this period are levels of the isotopes carbon-14 and beryllium-10.[87]

Volcanic activity

In a 2012 paper, Miller et al. link the Little Ice Age to an "unusual 50-year-long episode with four large sulfur-rich explosive eruptions, each with global sulfate loading >60 Tg" and notes that "large changes in solar irradiance are not required."[7]

Throughout the Little Ice Age, the world experienced heightened volcanic activity.[88] When a volcano erupts, its ash reaches high into the atmosphere and can spread to cover the whole earth. The ash cloud blocks out some of the incoming solar radiation, leading to worldwide cooling that can last up to two years after an eruption. Also emitted by eruptions is sulfur, in the form of sulfur dioxide gas. When it reaches the stratosphere, it turns into sulfuric acid particles, which reflect the sun's rays, further reducing the amount of radiation reaching Earth's surface.

A recent study found that an especially massive tropical volcanic eruption in 1257, possibly of the now-extinct Mount Samalas near Mount Rinjani, both in Lombok, Indonesia, followed by three smaller eruptions in 1268, 1275, and 1284 did not allow the climate to recover. This may have caused the initial cooling, and the 1452–53 eruption of Kuwae in Vanuatu triggered a second pulse of cooling.[7] The cold summers can be maintained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks long after volcanic aerosols are removed.

Other volcanoes that erupted during the era and may have contributed to the cooling include Billy Mitchell (ca. 1580), Huaynaputina (1600), Mount Parker (1641), Long Island (Papua New Guinea) (ca. 1660), and Laki (1783).[23] The 1815 eruption of Tambora, also in Indonesia, blanketed the atmosphere with ash; the following year, 1816, came to be known as the Year Without a Summer,[89] when frost and snow were reported in June and July in both New England and Northern Europe.

Ocean circulation

Another possibility is that there was a slowing of thermohaline circulation.[51][82][90][91] The circulation could have been interrupted by the introduction of a large amount of fresh water into the North Atlantic, possibly caused by a period of warming before the Little Ice Age known as the Medieval Warm Period.[33][92][93] There is some concern that a shutdown of thermohaline circulation could happen again as a result of the present warming period.[94][95]

Decreased human populations

Some researchers have proposed that human influences on climate began earlier than is normally supposed (see Early anthropocene for more details) and that major population declines in Eurasia and the Americas reduced this impact, leading to a cooling trend.

The Black Death is estimated to have killed 30% to 60% of Europe's population.[96] In total, the plague may have reduced the world population from an estimated 475 million to 350–375 million in the 14th century.[97] It took 200 years for the world population to recover to its previous level.[98] William Ruddiman proposed that these large population reductions in Europe, East Asia, and the Middle East caused a decrease in agricultural activity. Ruddiman suggests reforestation took place, allowing more carbon dioxide uptake from the atmosphere, which may have been a factor in the cooling noted during the Little Ice Age. Ruddiman further hypothesized that a reduced population in the Americas after European contact in the 16th century could have had a similar effect.[99][100] Other researchers supported depopulation in the Americas as a factor, asserting that humans had cleared considerable amounts of forest to support agriculture in the Americas before the arrival of Europeans brought on a population collapse.[101][102] Richard Nevle, Robert Dull and colleagues further suggested that not only anthropogenic forest clearance played a role in reducing the amount of carbon sequestered in Neotropical forests, but that human-set fires played a central role in reducing biomass in Amazonian and Central American forests before the arrival of Europeans and the concomitant spread of diseases during the Columbian exchange.[103][104][105] Dull and Nevle calculated that reforestation in the tropical biomes of the Americas alone from 1500 to 1650 accounted for net carbon sequestration of 2-5 Pg.[104] Brierley conjectured that European arrival in the Americas caused mass deaths from epidemic disease, which caused much abandonment of farmland, which caused much return of forest, which sequestered greater levels of carbon dioxide.[12] A study of sediment cores and soil samples further suggests that carbon dioxide uptake via reforestation in the Americas could have contributed to the Little Ice Age.[106] The depopulation is linked to a drop in carbon dioxide levels observed at Law Dome, Antarctica.[101] A 2011 study by the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology asserts that the Mongol invasions and conquests, which lasted almost two centuries, contributed to global cooling by depopulating vast regions and allowing for the return of carbon absorbing forest over cultivated land.[107]

Increased human populations

It has been speculated that increased human populations living at high latitudes caused the Little Ice Age through deforestation. The increased albedo due to this deforestation (more reflection of solar rays from snow-covered ground than dark, tree-covered area) could have had a profound effect on global temperatures.[108]

Inherent variability of climate

Spontaneous fluctuations in global climate might explain past variability. It is very difficult to know what the true level of variability from internal causes might be given the existence of other forces, as noted above, whose magnitude may not be known. One approach to evaluating internal variability is to use long integrations of coupled ocean-atmosphere global climate models. They have the advantage that the external forcing is known to be zero, but the disadvantage is that they may not fully reflect reality. The variations may result from chaos-driven changes in the oceans, the atmosphere, or interactions between the two.[109] Two studies have concluded that the demonstrated inherent variability is not great enough to account for the Little Ice Age.[109][110] The severe winters of 1770 to 1772 in Europe, however, have been attributed to an anomaly in the North Atlantic oscillation.[111]

See also

- 1500-year climate cycle

- 8.2 kiloyear event – Sudden decrease in global temperatures c. 6200 BCE

- Historical climatology

- Late Antique Little Ice Age

- Paleoclimatology – Study of changes in ancient climate

- Retreat of glaciers since 1850 – Shortening of glaciers by melting

- Year Without a Summer – 1816, a volcanic winter event during the Little Ice Age

- Younger Dryas – Time period

References

- Hawkins, Ed (30 January 2020). "2019 years". climate-lab-book.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. ("The data show that the modern period is very different to what occurred in the past. The often quoted Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age are real phenomena, but small compared to the recent changes.")

- Ladurie, Emmanuel Le Roy (1971). Times of Feast, Times of Famine: a History of Climate Since the Year 1000. Barbara Bray. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-374-52122-6. OCLC 164590.

- Matthes, François E. (1939). "Report of Committee on Glaciers, April 1939". Transactions, American Geophysical Union. 20 (4): 518. Bibcode:1939TrAGU..20..518M. doi:10.1029/TR020i004p00518. Matthes described glaciers in the Sierra Nevada of California that he believed could not have survived the hypsithermal; his usage of "Little Ice Age" has been superseded by "Neoglaciation".

- Mann, Michael (2003). "Little Ice Age" (PDF). In Michael C MacCracken; John S Perry (eds.). Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change, Volume 1, The Earth System: Physical and Chemical Dimensions of Global Environmental Change. John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- Lamb, HH (1972). "The cold Little Ice Age climate of about 1550 to 1800". Climate: present, past and future. London: Methuen. p. 107. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.408.1689. ISBN 978-0-416-11530-7. (noted in Grove 2004:4).

- "Earth observatory Glossary L-N". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Green Belt MD: NASA. Retrieved 17 July 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Miller, Gifford H.; Geirsdóttir, Áslaug; Zhong, Yafang; Larsen, Darren J.; Otto-Bliesner, Bette L.; Holland, Marika M.; Bailey, David A.; Refsnider, Kurt A.; Lehman, Scott J.; Southon, John R.; Anderson, Chance; Björnsson, Helgi; Thordarson, Thorvaldur (2012). "Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks". Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (2): n/a. Bibcode:2012GeoRL..39.2708M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.639.9076. doi:10.1029/2011GL050168. Lay summary – Science Daily (30 January 2012).

- Grove, J.M., Little Ice Ages: Ancient and Modern, Routledge, London (2 volumes) 2004.

- Matthews, John A.; Briffa, Keith R. (2005). "The 'little ice age': Re‐evaluation of an evolving concept". Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography. 87: 17–36. doi:10.1111/j.0435-3676.2005.00242.x. S2CID 4832081.

- "1.4.3 Solar Variability and the Total Solar Irradiance – AR4 WGI Chapter 1: Historical Overview of Climate Change Science". Ipcc.ch. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". UNEP/GRID-Arendal. Archived from the original on 29 May 2006. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- Koch, Alexander; Brierley, Chris; Maslin, Mark M.; Lewis, Simon L. (2019). "Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492". Quaternary Science Reviews. 207: 13–36. Bibcode:2019QSRv..207...13K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.004.

- AR4 WG1 Section 6.6: The Last 2,000 Years, 2007.

- Jones, Philip D. (2001). History and climate: memories of the future?. Springer. p. 154.

- According to JM Lamb of Cambridge University the little ice age was already under way in Canada and Switzerland and in the wider North Atlantic region in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries

- "Worldwide glacier retreat". RealClimate. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- Oerlemans, J. (2005). "Extracting a Climate Signal from 169 Glacier Records". Science. 308 (5722): 675–677. Bibcode:2005Sci...308..675O. doi:10.1126/science.1107046. PMID 15746388. S2CID 26585604.

- Jonathan Amos (30 September 2013). "Mystery 13th Century eruption traced to Lombok, Indonesia". BBC.

The mystery event in 1257 was so large its chemical signature is recorded in the ice of both the Arctic and the Antarctic. European medieval texts talk of a sudden cooling of the climate, and of failed harvests.

- Hendy, Erica J.; Gagan, Michael K.; Alibert, Chantal A.; McCulloch, Malcolm T.; Lough, Janice M.; Isdale, Peter J. (2002). "Abrupt Decrease in Tropical Pacific Sea Surface Salinity at End of Little Ice Age". Science. 295 (5559): 1511–4. Bibcode:2002Sci...295.1511H. doi:10.1126/science.1067693. PMID 11859191. S2CID 25698190.

- Ogilvie, A.E.J.; Jónsson, T. (2001). "'Little Ice Age' Research: A Perspective from Iceland". Climatic Change. 48: 9–52. doi:10.1023/A:1005625729889.

- "About INQUA:Quaternary Science (By S.C. Porter)". INQUA. Archived from the original on 15 April 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- Meacham, Jon (7 May 2020). "Pandemics of the Past". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Jonathan Cowie (2007). Climate change: biological and human aspects. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-521-69619-7.

- Stone, R. (2004). "VOLCANOLOGY: Iceland's Doomsday Scenario?". Science. 306 (5700): 1278–1281. doi:10.1126/science.306.5700.1278. PMID 15550636.

- "What Did They Eat? — Icelandic food from the Settlement through the Middle Ages". Archived from the original on 20 February 2012.

- "SVS Science Story: Ice Age". NASA Scientific Visualization Studio. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- Lamb, Hubert H. (1995). "The little ice age". Climate, history and the modern world. London: Routledge. pp. 211–241. ISBN 978-0-415-12734-9.

- "Arquivo de eventos históricos – Página 4 – MeteoPT.com – Fórum de Meteorologia". MeteoPT.com. 17 July 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- Cullen, Karen J. (30 May 2010). Famine in Scotland: The 'Ill Years' of The 1690s. Edinburgh University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7486-3887-1.

- Ewanu, Elizabeth; Nugent, Janay (2 November 2008). Finding the Family in Medieval and Early Modern Scotland. Ashgate. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-7546-6049-1.

- Whitehouse, David (17 December 2003). "Stradivarius' sound 'due to Sun'". BBC.

- Burke, James (21 September 1978). "Thunder in the Skies". Connections. BBC.

- Fagan 2001

- Behringer, Wolfgang (1999). "Climatic change and witch-hunting: the impact of the Little Ice Age on mentalities". Climatic Change. 43: 335–351. doi:10.1023/A:1005554519604.

- Dagomar Degroot, The Frigid Golden Age: Climate Change, the Little Ice Age, and the Dutch Republic, 1560–1720 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018) ISBN 9781108419314

- Oster, Emily (2004). "Witchcraft, weather and economic growth in Renaissance Europe". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 18 (1): 215–228. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.526.7789. doi:10.1257/089533004773563502. JSTOR 3216882. SSRN 522403.

- Behringer, Wolfgang (2009). "Cultural Consequences of the Little Ice Age". A Cultural History of Climate. Wiley. pp. 121–167. ISBN 978-0-745-64529-2.

- Parker, Geoffrey (2013). "The Little Ice Age". Global Crisis: War, Climate Change, & Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century. Yale University Press. pp. 3–25. ISBN 978-0-300-20863-4.

- Lehmann, Hartmut (1988). "The Persecution of Witches as Restoration of Order: The Case of Germany, 1590s–1650s". Central European History. 21 (2): 107–121. doi:10.1017/S000893890001270X.

- Post, John D. (1984). "Climatic Variability and the European Mortality Wave of the Early 1740s". The Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 15 (1): 1–30. doi:10.2307/203592. JSTOR 203592. PMID 11617361.

- "Part 12 of Annals of Loch Cé". Corpus of Electronic Texts. University College Cork.

- Meigs, Samantha A. (13 October 1997). Reformations in Ireland: Tradition and Confessionalism, 1400–1690. Springer. ISBN 9781349257102 – via Google Books.

- Macdougall, Douglas (2004). Frozen Earth: The Once and Future Story of Ice Ages. University of California Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-520-24824-3.

- Huddart, David; Stott, Tim (6 April 2010). Earth Environments: Past, Present and Future. Wiley. p. 863. ISBN 978-0-470-74960-9.

- Dagomar Degroot (2018). The Frigid Golden Age: Climate Change, the Little Ice Age, and the Dutch Republic, 1560–1720. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108419314.

- Burroughs, William (18 December 1980). New Scientist. Reed Business Information. pp. 768–. ISSN 0262-4079. 1980 article in the New Scientist

- John E. Thornes; John Constable (1999). John Constable's skies: a fusion of art and science. Continuum International. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-902459-02-8.

- "Kilsyth Curling". Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- "The Story so Far!!!". Gourock Curling Club. 2009. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- Kenyon W.A.; Turnbull J.R. (1971). The Battle for James Bay. Toronto: Macmillan Company of Canada Limited.

- Broecker, Wallace S. (2000). "Was a change in thermohaline circulation responsible for the Little Ice Age?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (4): 1339–42. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.1339B. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.4.1339. JSTOR 121471. PMC 34299. PMID 10677462.

- "Ice Ages". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 12 April 2005.

- https://www.nps.gov/glba/learn/historyculture/people.htm

- Cronin, T. M.; Dwyer, G. S.; Kamiya, T.; Schwede, S.; Willard, D. A. (2003). "Medieval Warm Period, Little Ice Age and 20th century temperature variability from Chesapeake Bay" (PDF). Global and Planetary Change. 36 (1): 17. Bibcode:2003GPC....36...17C. doi:10.1016/S0921-8181(02)00161-3. hdl:10161/6578.

- Hodell, David A.; Brenner, Mark; Curtis, Jason H.; Medina-González, Roger; Ildefonso-Chan Can, Enrique; Albornaz-Pat, Alma; Guilderson, Thomas P. (2005). "Climate change on the Yucatan Peninsula during the Little Ice Age". Quaternary Research. 63 (2): 109. Bibcode:2005QuRes..63..109H. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2004.11.004.

- Bond et al., 1997

- "Abrupt Climate Changes Revisited: How Serious and How Likely?". USGCRP Seminar. US Global Change Research Program. 23 February 1998.

- Reiter, Paul (2000). "From Shakespeare to Defoe: Malaria in England in the Little Ice Age". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 6 (1): 1–11. doi:10.3201/eid0601.000101. PMC 2627969. PMID 10653562.

- Liu, Kam-biu; Shen, Caiming; Louie, Kin-Sheun (2001). "A 1,000-Year History of Typhoon Landfalls in Guangdong, Southern China, Reconstructed from Chinese Historical Documentary Records". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 91 (3): 453–464. doi:10.1111/0004-5608.00253. S2CID 53066209.

- Fan, Ka-wai (2010). "Climatic change and dynastic cycles in Chinese history: A review essay". Climatic Change. 101 (3–4): 565–573. Bibcode:2010ClCh..101..565F. doi:10.1007/s10584-009-9702-3.

- "From Zardaris to Makranis: How the Baloch came to Sindh". The Express Tribune. 28 March 2014.

- Johnson, Thomas C.; Barry, Sylvia L.; Chan, Yvonne; Wilkinson, Paul (2001). "Decadal record of climate variability spanning the past 700 yr in the Southern Tropics of East Africa". Geology. 29 (1): 83. Bibcode:2001Geo....29...83J. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0083:DROCVS>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 20364249.

- Holmgren, K., Tyson, P.D., Moberg, A., Svanered, O. (2001). "A preliminary 3000-year regional temperature reconstruction for South Africa". South African Journal of Science. 97: 49–51. hdl:10520/EJC97278.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- MacKay, Anson W.; Bamford, Marion K.; Grab, Stefan W.; Fitchett, Jennifer M. (2016). "A multi-disciplinary review of late Quaternary palaeoclimates and environments for Lesotho". South African Journal of Science. 112. doi:10.17159/sajs.2016/20160045.

- Kreutz, K. J. (1997). "Bipolar Changes in Atmospheric Circulation During the Little Ice Age". Science. 277 (5330): 1294–1296. doi:10.1126/science.277.5330.1294. S2CID 129868172.

- Khim, Boo-Keun; Yoon, Ho Il; Kang, Cheon Yun; Bahk, Jang Jun (2002). "Unstable Climate Oscillations during the Late Holocene in the Eastern Bransfield Basin, Antarctic Peninsula". Quaternary Research. 58 (3): 234. Bibcode:2002QuRes..58..234K. doi:10.1006/qres.2002.2371.

- "Siple Dome Glaciochemistry". Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- Sarah B. Das; Richard B. Alley. "Clues to changing WAIS Holocene summer temperatures from variations in melt-layer frequency in the Siple Dome ice core". Archived from the original on 7 October 2006.

- D.M. Etheridge; L.P. Steele; R.L. Langenfelds; R.J. Francey; J.-M. Barnola; V.I. Morgan. "Historical CO

2 Records from the Law Dome DE08, DE08-2, and DSS Ice Cores". Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, Tenn. - Bárcena, M. Angeles; Gersonde, Rainer; Ledesma, Santiago; Fabrés, Joan; Calafat, Antonio M.; Canals, Miquel; Sierro, F. Javier; Flores, Jose A. (1998). "Record of Holocene glacial oscillations in Bransfield Basin as revealed by siliceous microfossil assemblages". Antarctic Science. 10 (3): 269. Bibcode:1998AntSc..10..269B. doi:10.1017/S0954102098000364.

- Rhodes, R. H.; Bertler, N. A. N.; Baker, J. A.; Steen-Larsen, H. C.; Sneed, S. B.; Morgenstern, U.; Johnsen, S. J. (2012). "Little Ice Age climate and oceanic conditions of the Ross Sea, Antarctica from a coastal ice core record". Climate of the Past. 8 (4): 1223. Bibcode:2012CliPa...8.1223R. doi:10.5194/cp-8-1223-2012.

- Pollack, Henry N.; Huang, Shaopeng; Smerdon, Jason E. (2006). "Five centuries of climate change in Australia: The view from underground". Journal of Quaternary Science. 21 (7): 701. Bibcode:2006JQS....21..701P. doi:10.1002/jqs.1060.

- Winkler, Stefan (2000). "The 'Little Ice Age' maximum in the Southern Alps, New Zealand: Preliminary results at Mueller Glacier". The Holocene. 10 (5): 643–647. Bibcode:2000Holoc..10..643W. doi:10.1191/095968300666087656.

- Nunn, Patrick D. (2000). "Environmental catastrophe in the Pacific Islands around A.D. 1300". Geoarchaeology. 15 (7): 715–740. doi:10.1002/1520-6548(200010)15:7<715::AID-GEA4>3.0.CO;2-L.

- Kim M. Cobb; Chris Charles; Hai Cheng; R. Lawrence Edwards. "The Medieval Cool Period and the Little Warm Age in the Central Tropical Pacific? Fossil Coral Climate Records of the Last Millennium". Archived from the original on 20 November 2003.

- Villalba, Ricardo (1990). "Climatic fluctuations in northern Patagonia during the last 1000 years as inferred from tree-ring records". Quaternary Research. 34 (3): 346–360. Bibcode:1990QuRes..34..346V. doi:10.1016/0033-5894(90)90046-N.

- Villalba, Ricardo (1994). "Tree-ring and glacial evidence for the medieval warm epoch and the little ice age in southern South America". Climatic Change. 26 (2–3): 183–197. Bibcode:1994ClCh...26..183V. doi:10.1007/BF01092413.

- Bertrand, Sébastien; Boës, Xavier; Castiaux, Julie; Charlet, François; Urrutia, Roberto; Espinoza, Cristian; Lepoint, Gilles; Charlier, Bernard; Fagel, Nathalie (2005). "Temporal evolution of sediment supply in Lago Puyehue (Southern Chile) during the last 600 yr and its climatic significance". Quaternary Research. 64 (2): 163. Bibcode:2005QuRes..64..163B. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2005.06.005.

- Meyer, Inka; Wagner, Sebastian (2009). "The Little Ice Age in Southern South America: Proxy and Model Based Evidence". Past Climate Variability in South America and Surrounding Regions. Developments in Paleoenvironmental Research. 14. pp. 395–412. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2672-9_16. ISBN 978-90-481-2671-2.

- Thompson, L. G.; Mosley-Thompson, E.; Davis, M. E.; Lin, P. N.; Henderson, K.; Mashiotta, T. A. (2003). "Tropical Glacier and Ice Core Evidence of Climate Change on Annual to Millennial Time Scales". Climate Variability and Change in High Elevation Regions: Past, Present & Future. Advances in Global Change Research. 15. p. 137. doi:10.1007/978-94-015-1252-7_8. ISBN 978-90-481-6322-9.

- Araneda, Alberto; Torrejón, Fernando; Aguayo, Mauricio; Torres, Laura; Cruces, Fabiola; Cisternas, Marco; Urrutia, Roberto (2007). "Historical records of San Rafael glacier advances (North Patagonian Icefield): Another clue to 'Little Ice Age' timing in southern Chile?". The Holocene. 17 (7): 987. Bibcode:2007Holoc..17..987A. doi:10.1177/0959683607082414.

- Wanamaker, Alan D.; Butler, Paul G.; Scourse, James D.; Heinemeier, Jan; Eiríksson, Jón; Knudsen, Karen Luise; Richardson, Christopher A. (2012). "Surface changes in the North Atlantic meridional overturning circulation during the last millennium". Nature Communications. 3: 899. Bibcode:2012NatCo...3..899W. doi:10.1038/ncomms1901. PMC 3621426. PMID 22692542.

- Kaufman, D. S.; Schneider, D. P.; McKay, N. P.; Ammann, C. M.; Bradley, R. S.; Briffa, K. R.; Miller, G. H.; Otto-Bliesner, B. L.; Overpeck, J. T.; Vinther, B. M.; Abbott, M.; Axford, M.; Bird, Y.; Birks, B.; Bjune, H. J. B.; Briner, A. E.; Cook, J.; Chipman, T.; Francus, M.; Gajewski, P.; Geirsdottir, K.; Hu, A.; Kutchko, F. S.; Lamoureux, B.; Loso, S.; MacDonald, M.; Peros, G.; Porinchu, M.; Schiff, D.; Seppa, C.; Seppa, H.; Arctic Lakes 2k Project Members (2009). "Recent Warming Reverses Long-Term Arctic Cooling" (PDF). Science. 325 (5945): 1236–1239. Bibcode:2009Sci...325.1236K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.397.8778. doi:10.1126/science.1173983. PMID 19729653.

"Arctic Warming Overtakes 2,000 Years of Natural Cooling". UCAR. 3 September 2009. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

Bello, David (4 September 2009). "Global Warming Reverses Long-Term Arctic Cooling". Scientific American. Retrieved 19 May 2011. - Radiative Forcing of Climate Change: Expanding the Concept and Addressing Uncertainties, National Research Council, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., p. 29, 2005.

- Sunspot Activity at 8,000-Year High Space.com Astronomy 27 October 2004

- Geoffrey Parker; Lesley M. Smith (1997). The general crisis of the seventeenth century. Routledge. pp. 287, 288. ISBN 978-0-415-16518-1.

- Crowley, Thomas J. (2000). "Causes of Climate Change over the Past 1000 Years". Science. 289 (5477): 270–277. Bibcode:2000Sci...289..270C. doi:10.1126/science.289.5477.270. PMID 10894770. S2CID 1416961.

- Robock, Alan (1979). "The "Little Ice Age": Northern Hemisphere Average Observations and Model Calculations". Science. 206 (4425): 1402–1404. Bibcode:1979Sci...206.1402R. doi:10.1126/science.206.4425.1402. PMID 17739301.

- "Is the Meghalayan Event a Tipping Point in Geology?". The Wire.

- "A Chilling Possibility – NASA Science". Science.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- Hopkin, Michael (29 November 2006). "Gulf Stream weakened in 'Little Ice Age'". BioEd Online. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Villanueva, John Carl (19 October 2009). "Little Ice Age". Universe Today. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- Pittenger, Richard F.; Gagosian, Robert B. (October 2003). "Global Warming Could Have a Chilling Effect on the Military" (PDF). Defense Horizons. 33. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- Leake, Jonathan (8 May 2005). "Britain faces big chill as ocean current slows". The Times. London. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- "Little Ice Age, on season 15, episode 5". Scientific American Frontiers. Chedd-Angier Production Company. 2005. PBS. Archived from the original on 2006.

- Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A pest in the land: new world epidemics in a global perspective. University of New Mexico Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8263-2871-7.

- "Historical Estimates of World Population". Census.gov. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- Jay, Peter (17 July 2000). "A Distant Mirror". TIME Europe. 156 (3). Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Ravilious, Kate (27 February 2006). "Europe's chill linked to disease". BBC.

- Ruddiman, William F. (2003). "The Anthropogenic Greenhouse Era Began Thousands of Years Ago". Climatic Change. 61 (3): 261–293. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.651.2119. doi:10.1023/B:CLIM.0000004577.17928.fa.

- Faust, Franz X.; Gnecco, Cristóbal; Mannstein, Hermann; Stamm, Jörg (2006). "Evidence for the Postconquest Demographic Collapse of the Americas in Historical CO2 Levels" (PDF). Earth Interactions. 10 (11): 1. Bibcode:2006EaInt..10k...1F. doi:10.1175/EI157.1.

- R.J. Nevle et al., "Ecological-hydrological effects of reduced biomass burning in the neotropics after A.D. 1500," Geological Society of America Meeting, Minneapolis MN, 11 October 2011. abstract. Popular summary: "Columbus' arrival linked to carbon dioxide drop: Depopulation of Americas may have cooled climate," Science News, 5 November 2011. (access date 2 January 2012)

- Nevle, Richard J.; Bird, Dennis K. (7 July 2008). "Effects of syn-pandemic fire reduction and reforestation in the tropical Americas on atmospheric CO2 during European conquest". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 264 (1): 25–38. Bibcode:2008PPP...264...25N. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.03.008. ISSN 0031-0182.

- Dull, Robert A.; Nevle, Richard J.; Woods, William I.; Bird, Dennis K.; Avnery, Shiri; Denevan, William M. (31 August 2010). "The Columbian Encounter and the Little Ice Age: Abrupt Land Use Change, Fire, and Greenhouse Forcing". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 100 (4): 755–771. doi:10.1080/00045608.2010.502432. ISSN 0004-5608.

- Nevle, R.J.; Bird, D.K.; Ruddiman, W.F.; Dull, R.A. (1 August 2011). "Neotropical human–landscape interactions, fire, and atmospheric CO2 during European conquest". The Holocene. 21 (5): 853–864. Bibcode:2011Holoc..21..853N. doi:10.1177/0959683611404578. ISSN 0959-6836.

- Bergeron, Louis (17 December 2008). "Reforestation helped trigger Little Ice Age, researchers say". Stanford News Service.

- "War, Plague No Match For Deforestation In Driving CO2 Buildup". Carnegie Institution for Science. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Ellis, Erle C.; Kaplan, Jed O.; Fuller, Dorian Q.; Vavrus, Steve; Klein Goldewijk, Kees; Verburg, Peter H. (2013). "Used planet: A global history". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (20): 7978–85. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.7978E. doi:10.1073/pnas.1217241110. PMC 3657770. PMID 23630271.

- Free, Melissa; Robock, Alan (1999). "Global warming in the context of the Little Ice Age". Journal of Geophysical Research. 104 (D16): 19, 057. Bibcode:1999JGR...10419057F. doi:10.1029/1999JD900233.

- Hunt, B. G. (2006). "The Medieval Warm Period, the Little Ice Age and simulated climatic variability". Climate Dynamics. 27 (7–8): 677–694. Bibcode:2006ClDy...27..677H. doi:10.1007/s00382-006-0153-5.

- Collet, Dominik (2020). "Hungern und handeln". Damals (in German). No. 6. pp. 72–76.

Further reading

- Fagan, Brian M. (2001). The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History, 1300–1850. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02272-4.

- Parker, Geoffrey (2013). Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15323-1.

- White, Sam (2017). A Cold Welcome: The Little Ice Age and Europe's Encounter with North America. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97192-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Little Ice Age. |

- Abrupt Climate Change Information from the Ocean & Climate Change Institute, links to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution articles

- "The Next Ice Age". Discover. September 2002. (discussion of Woods Hole research)

- "Huascaran (Peru) Ice Core Data". NOAA/NGDC Paleoclimatology Program. 1995.

- Dansgaard cycles and the Little Ice Age (LIA) (It is not easy to see a LIA in the graphs.)

- Tyson, P.D.; Karlen, W.; Holmgren, K.; Heiss, G.A. (2000). "The Little Ice Age and Medieval Warming in South Africa" (PDF). South African Journal of Science. 96 (3): 121–6.

- Was El Niño unaffected by the Little Ice Age? (2002)

- Evidence for the Little Ice Age in Spain, circa 2003

- The Little Ice Age in Europe, updated 2009

- "The Little Ice Age, Ca. 1300–1870". Timeline of European Environmental History. undated review article

- What's wrong with the sun? (Nothing) (2008)

- HistoricalClimatology.com, links, resources, and feature articles on the Little Ice Age and its present-day relevance.

- Climate History Network, association of historical climatologists and climate historians, many of whom study the Little Ice Age and its social consequences.