History of music

Music is found in every known society, past and present, and is considered to be a cultural universal[1][2]. Since all people of the world, including the most isolated tribal groups, have a form of music, it may be concluded that music is likely to have been present in the ancestral population prior to the dispersal of humans around the world. Consequently, the first music may have been invented in Africa and then evolved to become a fundamental constituent of human life, using various different materials to make various instruments.[3][4]

A culture's music is influenced by all other aspects of that culture, including social and economic organization and experience, climate, access to technology and what religion is believed. The emotions and ideas that music expresses, the situations in which music is played and listened to, and the attitudes toward music players and composers all vary between regions and periods. "Music history" is the distinct subfield of musicology and history which studies music (particularly Western art music) from a chronological perspective.

Eras of music

| Western classical music eras | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prehistoric music

Prehistoric music, once more commonly called primitive music, is the name given to all music produced in preliterate cultures (prehistory), beginning somewhere in very late geological history. Prehistoric music is followed by ancient music in most of Europe (1500 BC) and later music in subsequent European-influenced areas, but still exists in isolated areas.

Prehistoric music thus technically includes all of the world's music that has existed before the advent of any currently extant historical sources concerning that music, for example, traditional Native American music of preliterate tribes and Australian Aboriginal music. However, it is more common to refer to the "prehistoric" music of non-European continents – especially that which still survives – as folk, indigenous or traditional music. The origin of music is unknown as it occurred prior to recorded history. Some suggest that the origin of music likely stems from naturally occurring sounds and rhythms. Human music may echo these phenomena using patterns, repetition and tonality. Even today, some cultures have certain instances of their music intending to imitate natural sounds. In some instances, this feature is related to shamanistic beliefs or practice.[5][6] It may also serve entertainment (game)[7][8] or practical (luring animals in hunt)[7] functions.

It is probable that the first musical instrument was the human voice itself, which can make a vast array of sounds, from singing, humming and whistling through to clicking, coughing and yawning. As for other musical instruments, in 2008 archaeologists discovered a bone flute in the Hohle Fels cave near Ulm, Germany.[9][10][11] Considered to be about 35,000 years old, the five-holed flute has a V-shaped mouthpiece and is made from a vulture wing bone. The oldest known wooden pipes were discovered near Greystones, Ireland, in 2004. A wood-lined pit contained a group of six flutes made from yew wood, between 30 and 50 cm long, tapered at one end, but without any finger holes. They may once have been strapped together.[12]

It has been suggested that the "Divje Babe Flute", a cave bear femur dated to be between 50,000 and 60,000 years old, is the world's oldest musical instrument and was produced by Neanderthals.[13][14] Claims that the femur is indeed a musical instrument are, however, contested by alternative theories including the suggestion that the femur may have been gnawed by carnivores to produce holes.[15]

Ancient music

"Ancient music" is the name given to the music that follows music of the prehistoric era. The "oldest known song" was written in cuneiform, dating to 3400 years ago from Ugarit in Syria. It was a part of the Hurrian songs, more specifically Hurrian hymn no. 6. It was deciphered by Anne Draffkorn Kilmer, and was demonstrated to be composed in harmonies of thirds, like ancient gymel,[16] and also was written using a Pythagorean tuning of the diatonic scale. The oldest surviving example of a complete musical composition, including musical notation, from anywhere in the world, is the Seikilos epitaph, dated to either the 1st or the 2nd century AD.

Double pipes, such as those used by the ancient Greeks, and ancient bagpipes, as well as a review of ancient drawings on vases and walls, etc., and ancient writings (such as in Aristotle, Problems, Book XIX.12) which described musical techniques of the time, indicate polyphony. One pipe in the aulos pairs (double flutes) likely served as a drone or "keynote," while the other played melodic passages. Instruments, such as the seven holed flute and various types of stringed instruments have been recovered from the Indus valley civilization archaeological sites.[17]

Indian classical music (marga) can be found from the scriptures of the Hindu tradition, the Vedas. Samaveda, one of the four vedas, describes music at length.

Ravanahatha (ravanhatta, rawanhattha, ravanastron or ravana hasta veena) is a bowed fiddle popular in Western India. It is believed to have originated among the Hela civilization of Sri Lanka in the time of King Ravana. This string instrument has been recognised as one of the oldest string instruments in world history.

The history of musical development in Iran (Persian music) dates back to the prehistoric era. The great legendary king, Jamshid, is credited with the invention of music. Music in Iran can be traced back to the days of the Elamite Empire (2500–644 BC). Fragmentary documents from various periods of the country's history establish that the ancient Persians possessed an elaborate musical culture. The Sassanid period (AD 226–651), in particular, has left us ample evidence pointing to the existence of a lively musical life in Persia. The names of some important musicians such as Barbod, Nakissa and Ramtin, and titles of some of their works have survived.

The Early music era may also include contemporary but traditional or folk music, including Asian music, Persian music, music of India, Jewish music, Greek music, Roman music, the music of Mesopotamia, the music of Egypt, and Muslim music.

Greece

Greek written history extends far back into Ancient Greece, and was a major part of ancient Greek theatre. In ancient Greece, mixed-gender choruses performed for entertainment, celebration and spiritual reasons. Instruments included the double-reed aulos and the plucked string instrument, the lyre, especially the special kind called a kithara. Music was an important part of education in ancient Greece, and boys were taught music starting at age six.

Biblical period

c. 960, Constantinople

According to Easton's Bible Dictionary, Jubal was named by the Bible as the inventor of musical instruments (Gen. 4:21). The Hebrews were much given to the cultivation of music. Their whole history and literature afford abundant evidence of this. After the Deluge, the first mention of music is in the account of Laban's interview with Jacob (Gen. 31:27). After their triumphal passage of the Red Sea, Moses and the children of Israel sang their song of deliverance (Ex. 15). But the period of Samuel, David, and Solomon was the golden age of Hebrew music, as it was of Hebrew poetry. Music was now for the first time systematically cultivated. It was an essential part of training in the schools of the prophets (1 Sam. 10:5). There now arose also a class of professional singers (2 Sam. 19:35; Eccl. 2:8). Solomon's Temple, however, was the great school of music. In the conducting of its services large bands of trained singers and players on instruments were constantly employed (2 Sam. 6:5; 1 Chr. 15:16; 23;5; 25:1–6). In private life also music seems to have held an important place among the Hebrews (Eccl. 2:8; Amos 6:4–6; Isa. 5:11, 12; 24:8, 9; Ps. 137; Jer. 48:33; Luke 15:25).[18]

Music and theatre scholars studying the history and anthropology of Semitic and early Judeo-Christian culture, have also discovered common links between theatrical and musical activity in the classical cultures of the Hebrews with those of the later cultures of the Greeks and Romans. The common area of performance is found in a "social phenomenon called litany," a form of prayer consisting of a series of invocations or supplications. The Journal of Religion and Theatre notes that among the earliest forms of litany, "Hebrew litany was accompanied by a rich musical tradition:"[19]

- While Genesis 4.21 identifies Jubal as the "father of all such as handle the harp and pipe", the Pentateuch is nearly silent about the practice and instruction of music in the early life of Israel. Then, in I Samuel 10 and the texts which follow, a curious thing happens. "One finds in the biblical text", writes Alfred Sendrey, "a sudden and unexplained upsurge of large choirs and orchestras, consisting of thoroughly organized and trained musical groups, which would be virtually inconceivable without lengthy, methodical preparation." This has led some scholars to believe that the prophet Samuel was the patriarch of a school which taught not only prophets and holy men, but also sacred-rite musicians. This public music school, perhaps the earliest in recorded history, was not restricted to a priestly class—which is how the shepherd boy David appears on the scene as a minstrel to King Saul.[19]

Early music

Early music is music of the European classical tradition from after the fall of the Roman Empire, in 476 AD, until the end of the Baroque era in the middle of the 18th century. Music within this enormous span of time was extremely diverse, encompassing multiple cultural traditions within a wide geographic area; many of the cultural groups out of which medieval Europe developed already had musical traditions, about which little is known. What unified these cultures in the Middle Ages was the Roman Catholic Church, and its music served as the focal point for musical development for the first thousand years of this period.

Western art music

| Periods, eras, and movements of Western classical music | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early period | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Common practice period | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Late 19th-century to 20th- and 21st-centuries | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Medieval music

While musical life was undoubtedly rich in the early Medieval era, as attested by artistic depictions of instruments, writings about music, and other records, the only repertory of music which has survived from before 800 to the present day is the plainsong liturgical music of the Roman Catholic Church, the largest part of which is called Gregorian chant. Pope Gregory I, who gave his name to the musical repertory and may himself have been a composer, is usually claimed to be the originator of the musical portion of the liturgy in its present form, though the sources giving details on his contribution date from more than a hundred years after his death. Many scholars believe that his reputation has been exaggerated by legend. Most of the chant repertory was composed anonymously in the centuries between the time of Gregory and Charlemagne.

During the 9th century several important developments took place. First, there was a major effort by the Church to unify the many chant traditions, and suppress many of them in favor of the Gregorian liturgy. Second, the earliest polyphonic music was sung, a form of parallel singing known as organum. Third, and of greatest significance for music history, notation was reinvented after a lapse of about five hundred years, though it would be several more centuries before a system of pitch and rhythm notation evolved having the precision and flexibility that modern musicians take for granted.

Several schools of polyphony flourished in the period after 1100: the St. Martial school of organum, the music of which was often characterized by a swiftly moving part over a single sustained line; the Notre Dame school of polyphony, which included the composers Léonin and Pérotin, and which produced the first music for more than two parts around 1200; the musical melting-pot of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, a pilgrimage destination and site where musicians from many traditions came together in the late Middle Ages, the music of whom survives in the Codex Calixtinus; and the English school, the music of which survives in the Worcester Fragments and the Old Hall Manuscript. Alongside these schools of sacred music a vibrant tradition of secular song developed, as exemplified in the music of the troubadours, trouvères and Minnesänger. Much of the later secular music of the early Renaissance evolved from the forms, ideas, and the musical aesthetic of the troubadours, courtly poets and itinerant musicians, whose culture was largely exterminated during the Albigensian Crusade in the early 13th century.

Forms of sacred music which developed during the late 13th century included the motet, conductus, discant, and clausulae. One unusual development was the Geisslerlieder, the music of wandering bands of flagellants during two periods: the middle of the 13th century (until they were suppressed by the Church); and the period during and immediately following the Black Death, around 1350, when their activities were vividly recorded and well-documented with notated music. Their music mixed folk song styles with penitential or apocalyptic texts. The 14th century in European music history is dominated by the style of the ars nova, which by convention is grouped with the medieval era in music, even though it had much in common with early Renaissance ideals and aesthetics. Much of the surviving music of the time is secular, and tends to use the formes fixes: the ballade, the virelai, the lai, the rondeau, which correspond to poetic forms of the same names. Most pieces in these forms are for one to three voices, likely with instrumental accompaniment: famous composers include Guillaume de Machaut and Francesco Landini.

Renaissance music

The beginning of the Renaissance in music is not as clearly marked as the beginning of the Renaissance in the other arts, and unlike in the other arts, it did not begin in Italy, but in northern Europe, specifically in the area currently comprising central and northern France, the Netherlands, and Belgium. The style of the Burgundian composers, as the first generation of the Franco-Flemish school is known, was at first a reaction against the excessive complexity and mannered style of the late 14th century ars subtilior, and contained clear, singable melody and balanced polyphony in all voices. The most famous composers of the Burgundian school in the mid-15th century are Guillaume Dufay, Gilles Binchois, and Antoine Busnois.

By the middle of the 15th century, composers and singers from the Low Countries and adjacent areas began to spread across Europe, especially into Italy, where they were employed by the papal chapel and the aristocratic patrons of the arts (such as the Medici, the Este, and the Sforza families). They carried their style with them: smooth polyphony which could be adapted for sacred or secular use as appropriate. Principal forms of sacred musical composition at the time were the mass, the motet, and the laude; secular forms included the chanson, the frottola, and later the madrigal.

The invention of printing had an immense influence on the dissemination of musical styles, and along with the movement of the Franco-Flemish musicians, contributed to the establishment of the first truly international style in European music since the unification of Gregorian chant under Charlemagne. Composers of the middle generation of the Franco-Flemish school included Johannes Ockeghem, who wrote music in a contrapuntally complex style, with varied texture and an elaborate use of canonical devices; Jacob Obrecht, one of the most famous composers of masses in the last decades of the 15th century; and Josquin des Prez, probably the most famous composer in Europe before Palestrina, and who during the 16th century was renowned as one of the greatest artists in any form. Music in the generation after Josquin explored increasing complexity of counterpoint; possibly the most extreme expression is in the music of Nicolas Gombert, whose contrapuntal complexities influenced early instrumental music, such as the canzona and the ricercar, ultimately culminating in Baroque fugal forms.

By the middle of the 16th century, the international style began to break down, and several highly diverse stylistic trends became evident: a trend towards simplicity in sacred music, as directed by the Counter-Reformation Council of Trent, exemplified in the music of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina; a trend towards complexity and chromaticism in the madrigal, which reached its extreme expression in the avant-garde style of the Ferrara School of Luzzaschi and the late century madrigalist Carlo Gesualdo; and the grandiose, sonorous music of the Venetian school, which used the architecture of the Basilica San Marco di Venezia to create antiphonal contrasts. The music of the Venetian school included the development of orchestration, ornamented instrumental parts, and continuo bass parts, all of which occurred within a span of several decades around 1600. Famous composers in Venice included the Gabrielis, Andrea and Giovanni, as well as Claudio Monteverdi, one of the most significant innovators at the end of the era.

Most parts of Europe had active and well-differentiated musical traditions by late in the century. In England, composers such as Thomas Tallis and William Byrd wrote sacred music in a style similar to that written on the continent, while an active group of home-grown madrigalists adapted the Italian form for English tastes: famous composers included Thomas Morley, John Wilbye and Thomas Weelkes. Spain developed instrumental and vocal styles of its own, with Tomás Luis de Victoria writing refined music similar to that of Palestrina, and numerous other composers writing for the new guitar. Germany cultivated polyphonic forms built on the Protestant chorales, which replaced the Roman Catholic Gregorian Chant as a basis for sacred music, and imported the style of the Venetian school (the appearance of which defined the start of the Baroque era there). In addition, German composers wrote enormous amounts of organ music, establishing the basis for the later Baroque organ style which culminated in the work of J.S. Bach. France developed a unique style of musical diction known as musique mesurée, used in secular chansons, with composers such as Guillaume Costeley and Claude Le Jeune prominent in the movement.

One of the most revolutionary movements in the era took place in Florence in the 1570s and 1580s, with the work of the Florentine Camerata, who ironically had a reactionary intent: dissatisfied with what they saw as contemporary musical depravities, their goal was to restore the music of the ancient Greeks. Chief among them were Vincenzo Galilei, the father of the astronomer, and Giulio Caccini. The fruits of their labors was a declamatory melodic singing style known as monody, and a corresponding staged dramatic form: a form known today as opera. The first operas, written around 1600, also define the end of the Renaissance and the beginning of the Baroque eras.

Music prior to 1600 was modal rather than tonal. Several theoretical developments late in the 16th century, such as the writings on scales on modes by Gioseffo Zarlino and Franchinus Gaffurius, led directly to the development of common practice tonality. The major and minor scales began to predominate over the old church modes, a feature which was at first most obvious at cadential points in compositions, but gradually became pervasive. Music after 1600, beginning with the tonal music of the Baroque era, is often referred to as belonging to the common practice period.

Baroque music

.jpg)

| J.S. Bach Toccata and Fugue |

|---|

The Baroque era took place from 1600 to 1750, as the Baroque artistic style flourished across Europe and, during this time, music expanded in its range and complexity. Baroque music began when the first operas (dramatic solo vocal music accompanied by orchestra) were written. During the Baroque era, polyphonic contrapuntal music, in which multiple, simultaneous independent melody lines were used, remained important (counterpoint was important in the vocal music of the Medieval era). German, Italian, French, Dutch, Polish, Spanish, Portuguese, and English Baroque composers wrote for small ensembles including strings, brass, and woodwinds, as well as for choirs and keyboard instruments such as pipe organ, harpsichord, and clavichord. During this period several major music forms were defined that lasted into later periods when they were expanded and evolved further, including the fugue, the invention, the sonata, and the concerto.[20] The late Baroque style was polyphonically complex and richly ornamented. Important composers from the Baroque era include Johann Sebastian Bach, Arcangelo Corelli, François Couperin, Girolamo Frescobaldi, George Frideric Handel, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Claudio Monteverdi, Georg Philipp Telemann and Antonio Vivaldi.

Classical music era

The music of the Classical period is characterized by homophonic texture, or an obvious melody with accompaniment. These new melodies tended to be almost voice-like and singable, allowing composers to actually replace singers as the focus of the music. Instrumental music therefore quickly replaced opera and other sung forms (such as oratorio) as the favorite of the musical audience and the epitome of great composition. However, opera did not disappear: during the classical period, several composers began producing operas for the general public in their native languages (previous operas were generally in Italian).

Along with the gradual displacement of the voice in favor of stronger, clearer melodies, counterpoint also typically became a decorative flourish, often used near the end of a work or for a single movement. In its stead, simple patterns, such as arpeggios and, in piano music, Alberti bass (an accompaniment with a repeated pattern typically in the left hand), were used to liven the movement of the piece without creating a confusing additional voice. The now-popular instrumental music was dominated by several well-defined forms: the sonata, the symphony, and the concerto, though none of these were specifically defined or taught at the time as they are now in music theory. All three derive from sonata form, which is both the overlying form of an entire work and the structure of a single movement. Sonata form matured during the Classical era to become the primary form of instrumental compositions throughout the 19th century.

The early Classical period was ushered in by the Mannheim School, which included such composers as Johann Stamitz, Franz Xaver Richter, Carl Stamitz, and Christian Cannabich. It exerted a profound influence on Joseph Haydn and, through him, on all subsequent European music. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was the central figure of the Classical period, and his phenomenal and varied output in all genres defines our perception of the period. Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert were transitional composers, leading into the Romantic period, with their expansion of existing genres, forms, and even functions of music.

Romantic music

In the Romantic period, music became more expressive and emotional, expanding to encompass literature, art, and philosophy. Famous early Romantic composers include Schumann, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Bellini, Donizetti, and Berlioz. The late 19th century saw a dramatic expansion in the size of the orchestra, and in the role of concerts as part of urban society. Famous composers from the second half of the century include Johann Strauss II, Brahms, Liszt, Tchaikovsky, Verdi, and Wagner. Between 1890 and 1910, a third wave of composers including Grieg, Dvořák, Mahler, Richard Strauss, Puccini, and Sibelius built on the work of middle Romantic composers to create even more complex – and often much longer – musical works. A prominent mark of late 19th century music is its nationalistic fervor, as exemplified by such figures as Dvořák, Sibelius, and Grieg. Other prominent late-century figures include Saint-Saëns, Fauré, Rachmaninoff, Franck, Debussy and Rimsky-Korsakov.

20th and 21st-century music

.jpg)

Music of all kinds also became increasingly portable. The 20th century saw a revolution in music listening as the radio gained popularity worldwide and new media and technologies were developed to record, capture, reproduce and distribute music. Music performances became increasingly visual with the broadcast and recording of performances.[21]

20th-century music brought a new freedom and wide experimentation with new musical styles and forms that challenged the accepted rules of music of earlier periods. The invention of musical amplification and electronic instruments, especially the synthesizer, in the mid-20th century revolutionized classical and popular music, and accelerated the development of new forms of music.[22]

As for classical music, two fundamental schools determined the course of the century: that of Arnold Schoenberg and that of Igor Stravinsky.[23]

Popular music

Popular music is music with wide appeal[24] that is typically distributed to large audiences through the music industry. These forms and styles can be enjoyed and performed by people with little or no musical training.[25]

The original application of the term is to music of the 1880s Tin Pan Alley period in the United States.[25] Although popular music sometimes is known as "pop music", the two terms are not interchangeable.[26] Popular music is a generic term for a wide variety of genres of music that appeal to the tastes of a large segment of the population,[27] whereas pop music usually refers to a specific musical genre within popular music.[28] Popular music songs and pieces typically have easily singable melodies. The song structure of popular music commonly involves repetition of sections, with the verse and chorus or refrain repeating throughout the song and the bridge providing a contrasting and transitional section within a piece.[29]

In an essay on popular music's history for Collier's Encyclopedia (1984), Robert Christgau explained, "Some sort of popular music has existed for as long as there has been an urban middle class to consume it. What distinguishes it above all is the aesthetic level it is aimed at. The cultural elite has always endowed music with an exalted if not self-important religious or aesthetic status, while for the rural folk, it has been practical and unselfconscious, an accompaniment to fieldwork or to the festivals that provide periodic escape from toil. But since Rome and Alexandria, professional entertainers have diverted and edified city dwellers with songs, marches, and dances, whose pretensions fell somewhere in between."[30]

Classical music outside Europe

Africa

Sub-Saharan African music is by a strong rhythmic interest that exhibits common characteristics in all regions of this vast territory, so that Arthur Morris Jones (1889–1980) has described the many local approaches as constituting one main system. C. K. also affirms the profound homogeneity of approach. West African rhythmic techniques carried over the Atlantic were fundamental ingredients in various musical styles of the Americas.

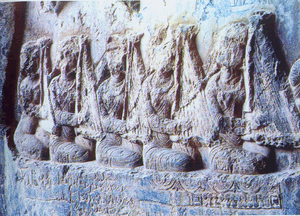

Byzantium

Byzantine music (Greek: Βυζαντινή Μουσική) is the music of the Byzantine Empire composed to Greek texts as ceremonial, festival, or church music. Greek and foreign historians agree that the ecclesiastical tones and in general the whole system of Byzantine music is closely related to the ancient Greek system. It remains the oldest genre of extant music, of which the manner of performance and (with increasing accuracy from the 5th century onwards) the names of the composers, and sometimes the particulars of each musical work's circumstances, are known.

Asia

Asian music covers the music cultures of Arabia, Central Asia, East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.

India

Indian music is one of the oldest musical traditions in the world.[31] The Indus Valley civilization left sculptures which show dance[32] and musical instruments (some no longer in use), like the seven holed flute. Various types of stringed instruments and drums have been recovered from Harrappa and Mohenjo Daro by excavations carried out by Sir Mortimer Wheeler.[33] The Rigveda has elements of present Indian music, with a musical notation to denote the metre and the mode of chanting.[34] Early Indian musical tradition also speaks of three accents and vocal music known as "Samagan" (Sama meaning melody and Gan meaning to sing).[35] The classical music of India includes two major traditions: the southern Carnatic music and the northern Hindustani classical music. India's classical music tradition is millennia long and remains important to the lives of Indians today as a source of religious inspiration, cultural expression, and entertainment.

Indian classical music (marga) is monophonic, and based on a single melody line or raga rhythmically organized through talas. Carnatic music is largely devotional; the majority of the songs are addressed to the Hindu deities. There are a lot of songs emphasising love and other social issues. In contrast to Carnatic music, Hindustani music was not only influenced by ancient Hindu musical traditions, Vedic philosophy and native Indian sounds but also by the Persian performance practices of the Afghan Mughals. The origins of Indian classical music can be found from the oldest of scriptures, part of the Hindu tradition, the Vedas. Samaveda, one of the four vedas describes music at length.

China

Chinese classical music is the traditional art or court music of China. It has a long history stretching for more than three thousand years. It has its own unique systems of musical notation, as well as musical tuning and pitch, musical instruments and styles or musical genres. Chinese music is pentatonic-diatonic, having a scale of twelve notes to an octave (5+7 = 12) as does European-influenced music.

Middle East

Persia

Persian music is the music of Persia and Persian language countries: musiqi, the science and art of music, and muzik, the sound and performance of music (Sakata 1983). See: Music of Iran, Music of Afghanistan, Music of Tajikistan, Music of Uzbekistan.

Samples

To the right are some music samples.

See also

- Music archaeology

Sources

- https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Sociology/Book%3A_Sociology_(Boundless)/03%3A_Culture/3.01%3A_Culture_and_Society/3.1C%3A_Cultural_Universals

- Gottlieb, Jed (2019-11-21). "Music everywhere". The Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 2020-08-04.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Wallin, Nils Lennart; Steven Brown; Björn Merker (2001). The Origins of Music. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-73143-0.

- Krause, Bernie (2012). The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World's Wild Places. New York: Little Brown/Hachette

- Hoppál 2006: 143 Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Diószegi 1960: 203

- Nattiez: 5

- Deschênes, Bruno (January 3, 2002). "Inuit Throat-Singing". www.mustrad.org.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- Conard, NJ (2009). "A female figurine from the basal Aurignacian of Hohle Fels Cave in southwestern Germany". Nature. 459 (7244): 248–52. doi:10.1038/nature07995. PMID 19444215.

- Wilford, John N. (June 24, 2009). "Flutes Offer Clues to Stone-Age Music". The New York Times. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- "Schwäbische Alb: Älteste Flöte vom Hohle Fels". epoc.de. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- "Wooden pipe find excites Irish archaeologists". abc.net.au. 10 May 2004. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- "The Neanderthal Flute". Divje-babe.si. 1 February 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- "Neanderthal flute – the oldest musical instrument in the world (60,000 years)". The National Museum of Slovenia. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- Cajus, Diedrich G. (1 April 2015). "'Neanderthal bone flutes': simply products of Ice Age spotted hyena scavenging activities on cave bear cubs in European cave bear dens". Royal Society Open Science. 2 – via Royal Society.

- Kilmer, Crocker, Brown, Sounds from Silence, 1976, Bit Enki, Berkeley, Calif., LCCN 76--16729

- Massey, Reginald; Massey, Jamila (28 March 1996). The Music of India. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-332-8. Retrieved 28 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- Easton's Bible Dictionary, "Music", 1897

- "A Theatre Before the World: Performance History at the Intersection of Hebrew, Greek, and Roman Religious Processional" The Journal of Religion and Theatre, Vol. 5, No. 1, Summer 2006.

- "Baroque Music by Elaine Thornburgh and Jack Logan, Ph.D." trumpet.sdsu.edu. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World: Performance and production. Volume II. A&C Black. 2003. p. 431.

- Michael Campbell (2012). Popular Music in America:The Beat Goes On. p. 24.

- Edward T. Cone, ed., Perspectives on Schoenberg and Stravinsky (1972)

- "Definition of "popular music" | Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Popular Music. (2015). Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia

- Lamb, Bill. "Pop Music Defined". About Entertainment. About.com. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- Allen, Robert. "Popular music". Pocket Fowler's Modern English Usage. 2004.

- Laurie, Timothy (2014). "Music Genre As Method". Cultural Studies Review. 20 (2), pp. 283-292.

- Sadie, Stanley, ed. (2001). "Popular Music: Form". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 20. New York: Grove. pp. 142–144. ISBN 978-0333608005.

- Christgau, Robert (1984). "Popular Music". In Halsey, William Darrach (ed.). Collier's Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 19, 2020 – via robertchristgau.com.

- World Music: The Basics By Nidel Nidel, Richard O. Nidel (p. 219)

- World History: Societies of the Past By Charles Kahn (p. 98)

- World History: Societies of the Past By Charles Kahn (p. 11)

- World Music: The Basics By Nidel Nidel, Richard O. Nidel (p. 10)

- The Music of India By Jamila Massey, Reginald Massey (p. 13)

- Sakata. 1983. .

Further reading

- Lee, Yuan-Yuan and Shen, Sinyan. (1999). Chinese Musical Instruments (Chinese Music Monograph Series). Chinese Music Society of North America Press. ISBN 1-880464-03-9

- Shen, Sinyan (1987). "Acoustics of Ancient Chinese Bells". Scientific American. 256 (4): 94. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0487-104.

- Merker, Brown, Steven, eds. (2000). The Origins of Music. The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-23206-5.

- Reese, Gustave (1954). Music in the Renaissance. New York, W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-09530-4.

- Bangayan, Phil, Bonet, Giselle and Ghosemajumder, Shuman (2002) "Digital Music Distribution" (History of the Recorded Music Industry), MIT Sloan School of Management.

- Hoppin, Richard H. (1978). Medieval Music. New York, W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-09090-6.

- Schwartz, Elliot and Godfrey, Daniel (1993). Music Since 1945. Simon & Schuster Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-873040-2

- Kilmer, Crocker, Brown, Sounds from Silence, 1976, Bit Enki, Berkeley, Calif., LCCN 76--16729.

- Helmholtz, Sensations of Tone Dover.

- Green, Emily. Dedicating Music, 1785–1850. University of Rochester Press, 2019.

- Harman, Carter (1956). A Popular History of Music: From Gregorian Chant to Jazz. Dell. The author was a music reporter for the New York Times and music editor of Time, as well as a composer.

External links

- The Dictionary of the History of Ideas see Music and Science, Music as a Demonic Art, Music as a Divine Art

- Edinburgh University Collection of Historic Musical Instruments

- Essentials of Music Classical Music eras, composers, glossary from Sony Music Entertainment

- Glossary of Musical Instruments & Styles and Quotes from OddMusic.com

- Historic American Sheet Music

- Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection popular American music, 1780–1960

- Music History Resources at GeoCities.com

- The Music History Webring

- The New Baroque and Renaissance Music Website at GeoCities.com

- National Music Museum from the University of South Dakota

- Tim Gracyk's Phonographs and Old Records

- U.S. popular music timeline

- Music History on Enjoy the Music.com

- Music Dedications Database