Muhammad in Medina

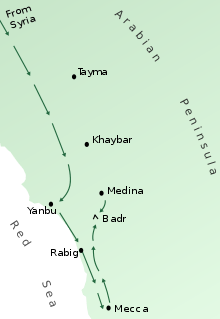

The Islamic prophet Muhammad came to Medina following the migration of his followers in what is known as the Hijra (migration to Medina) in 622. He had been invited to Medina by city leaders to adjudicate disputes between clans from which the city suffered.[1] He left Medina to return to and conquer Mecca in December 629.

Part of a series on Islam Islamic prophets |

|---|

|

|

Listed by Islamic name and Biblical name.

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

|

|

Views |

|

Related |

|

Hijra to Medina

A delegation from Medina, consisting of the representatives of the twelve important clans of Medina, invited Muhammad as a neutral outsider to serve as the chief arbitrator for the entire community.[1][2] There was fighting in Yathrib (Medina) mainly involving its Arab and Jewish inhabitants for around a hundred years before 620.[1] The recurring slaughters and disagreements over the resulting claims, especially after the battle of Bu'ath in which all the clans were involved, made it obvious to them that the tribal conceptions of blood-feud and an eye for an eye were no longer workable unless there was one man with authority to adjudicate in disputed cases.[1] The delegation from Medina pledged themselves and their fellow-citizens to accept Muhammad into their community and physically protect him as one of themselves.[3]

Muhammad instructed his followers to emigrate to Medina until virtually all of his followers had left Mecca. Being alarmed at the departure of Muslims, according to the tradition, the Meccans plotted to assassinate him. He instructed his cousin and future son-in-law Ali to sleep in his bed to trick the assassins that he had stayed (and to fight them off in his stead) and secretly slipped away from the town.[4] By 622, Muhammad had emigrated to Medina, then known as Yathrib, a large agricultural oasis.[3] Following the emigration, the Meccans seized the properties of the Muslim emigrants in Mecca.[5]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Among the things Muhammad did in order to settle the longstanding grievances among the tribes of Medina was drafting a document known as the Constitution of Medina (date debated), establishing a kind of brotherhood among the eight Medinan tribes and Muslim emigrants from Mecca, which specified the rights and duties of all citizens and the relationship of the different communities in Medina (including that of the Muslim community to other communities specifically the Jews and other "Peoples of the Book").[1][2] The community defined in the Constitution of Medina, umma, had a religious outlook but was also shaped by the practical considerations and substantially preserved the legal forms of the old Arab tribes.[3] Muhammad's adoption of facing north towards Jerusalem when performing the daily prayers (qibla) however need not to necessarily be a borrowing from the Jews as the reports about the direction of prayer before migration to Medina are contradictory and further this direction of prayer was also practiced among other groups in Arabia.

The first group of pagan converts to Islam in Medina were the clans who had not produced great leaders for themselves but had suffered from warlike leaders from other clans. This was followed by the general acceptance of Islam by the pagan population of Medina, apart from some exceptions. This was, according to Ibn Ishaq, influenced by the conversion to Islam of Sa'd ibn Mua'dh, one of the prominent leaders in Medina.

Relationship with followers of Abrahamic religions

In the course of Muhammad proselytizing in Mecca, he viewed Christians and Jews (both of whom he referred to as "People of the Book") as natural allies, part of the Abrahamic religions, sharing the core principles of his teachings, and anticipated their acceptance and support. Muslims, like Jews, were at that time praying towards Jerusalem. In the Constitution of Medina, Muhammad demanded the Jews' political loyalty in return for religious and cultural autonomy in many treaties.[6]

The Jewish clans however did not obey these treaties because of a feud with the Muslims though in the course of time there were a few converts from them.[7] After his migration to Medina, Muhammad's attitude towards Christians and Jews changed "because of experience of treachery". Norman Stillman states:[8]

During this fateful time, fraught with tension after the Hijra [migration to Medina], when Muhammad encountered contradiction, ridicule and rejection from the Jewish scholars in Medina, he came to adopt a radically more negative view of the people of the Book who had received earlier scriptures. This attitude was already evolving in the third Meccan period as the Prophet became more aware of the antipathy between Jews and Christians and the disagreements and strife amongst members of the same religion. The Qur'an at this time states that it will "relate [correctly] to the Children of Israel most of that about which they differ" (XXVII, 76).

Beginnings of armed conflict

Economically uprooted by their Meccan persecutors and with no available profession, the Muslim migrants turned to raiding Meccan caravans to respond to their persecution and to provide sustenance for their Muslim families, thus initiating armed conflict between the Muslims and the pagan Quraysh of Mecca.[9][10] Muhammad delivered Qur'anic verses permitting the Muslims, "those who have been expelled from their homes", to fight the Meccans in opposition to persecution (see Qur'an Sura 22 (Al-Hajj) Ayat 39-40[11]).[12] These attacks provoked and pressured Mecca by interfering with trade, and allowed the Muslims to acquire wealth, power and prestige while working toward their ultimate goal of inducing Mecca's submission to the new faith.[13][14]

In March 624, Muhammad led some three hundred warriors in a raid on a Meccan merchant caravan. The Muslims set an ambush for the Meccans at Badr.[15] Aware of the plan, the Meccan caravan eluded the Muslims. Meanwhile, a force from Mecca was sent to protect the caravan. The force did not return home upon hearing that the caravan was safe. The battle of Badr began in March 624.[16] Though outnumbered more than three to one, the Muslims won the battle, killing at least forty-five Meccans and taking seventy prisoners for ransom; only fourteen Muslims died. They had also succeeded in killing many of the Meccan leaders, including Abu Jahl.[17] Muhammad himself did not fight, directing the battle from a nearby hut alongside Abu Bakr.[18] In the weeks following the battle, Meccans visited Medina in order to ransom captives from Badr. Many of these had belonged to wealthy families, and were likely ransomed for a considerable sum. Those captives who were not sufficiently influential or wealthy were usually freed without ransom. Muhammad's decision was that those prisoners who refused to end their persecution of Muslims and were wealthy but did not ransom themselves should be killed.[19][20] Muhammad ordered the immediate execution of two Quraysh men without entertaining offers for their release.[20] Both men, which included Uqba ibn Abu Mu'ayt, had personally attempted to kill Muhammad in Mecca.[19] The raiders had won a lot of treasure, and the battle helped to stabilize the Medinan community.[21] Muhammad and his followers saw in the victory a confirmation of their faith and a prime importance in the affairs of Medina. Those remaining pagans in Medina were very bitter about the advance of Islam. In particular Asma bint Marwan and Abu 'Afak had composed verses insulting some of the Muslims and thereby violated the Constitution of Medina to which they belonged. These two were assassinated and Muhammad did not disapprove of it. No one dared to take vengeance on them, and some of the members of the clan of Asma bint Marwan who had previously converted to Islam in secret, now professed openly. This marked an end to the overt opposition to Muhammad among the pagans in Medina.[22]

Muhammad expelled from Medina the Banu Qaynuqa, one of the three main Jewish tribes.[3] Jewish opposition "may well have been for political as well as religious reasons".[23] On religious grounds, the Jews were skeptical of the possibility of a non-Jewish prophet,[24] and also had concerns about possible incompatibilities between the Qur'an and their own scriptures.[24][25] The Qur'an's response regarding the possibility of a non-Jew being a prophet was that Abraham was not a Jew. The Qur'an also stated that it was "restoring the pure monotheism of Abraham which had been corrupted in various, clearly specified, ways by Jews and Christians".[24] According to Francis Edward Peters, "The Jews also began secretly to connive with Muhammad's enemies in Mecca to overthrow him."[26]

Following the battle of Badr, Muhammad also made mutual-aid alliances with a number of Bedouin tribes to protect his community from attacks from the northern part of Hejaz.[3]

Conflict with Mecca

The attack at Badr committed Muhammad to total war with Meccans, who were now eager to avenge their defeat. To maintain their economic prosperity, the Meccans needed to restore their prestige, which had been lost at Badr.[27] The Meccans sent out a small party for a raid on Medina to restore confidence and reconnoitre. The party retreated immediately after a surprise and speedy attack but with minor damages; there was no combat.[28] In the ensuing months, Muhammad led expeditions on tribes allied with Mecca and sent out a raid on a Meccan caravan.[29] Abu Sufyan ibn Harb subsequently gathered an army of three thousand men and set out for an attack on Medina.[30] They were accompanied by some prominent women of Mecca, such as Hind bint Utbah, Abu Sufyan's wife, who had lost family members at Badr. These women provided encouragement in keeping with Bedouin custom, calling out the names of the dead at Badr.[31]

A scout alerted Muhammad of the Meccan army's presence and numbers a day later. The next morning, at the Muslim conference of war, there was dispute over how best to repel the Meccans. Muhammad and many of the senior figures suggested that it would be safer to fight within Medina and take advantage of its heavily fortified strongholds. Younger Muslims argued that the Meccans were destroying their crops, and that huddling in the strongholds would destroy Muslim prestige. Muhammad eventually conceded to the wishes of the latter, and readied the Muslim force for battle. Thus, Muhammad led his force outside to the mountain of Uhud (where the Meccans had camped) and fought the Battle of Uhud on March 23.[32][33]

Although the Muslim army had the best of the early encounters, indiscipline on the part of tactically placed archers led to a tactical defeat for the Muslim army, with 75 Muslims killed. However, the Meccans failed to achieve their goal of destroying the Muslims completely.[34] The Meccans did not occupy the town and withdrew to Mecca, since they were unable to attack Muhammad's position again, owing to military losses, low morale and the possibility of Muslim resistance in the town. There was also hope that Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy leading a group of Muslims in Medina could be won over by diplomacy.[35] Following the defeat, Muhammad's detractors in Medina said that if the victory at Badr was proof of the genuineness of his mission, then the defeat at Uhud was proof that his mission was not genuine.[36] Muhammad subsequently delivered Qur'anic verses 133-135 and 160-162 from the Al-i-Imran sura[37] indicating that the loss, however, was partly a punishment for disobedience and partly a test for steadfastness.[38]

The rousing of the nomads

In the battle of Uhud, the Meccans had collected all the available men from the Quraysh and the neighboring tribes friendly to them but had not succeeded in destroying the Muslim community. In order to raise a more powerful army, Abu Sufyan attracted the support of the great nomadic tribes to the north and east of Medina, using propaganda about Muhammad's weakness, promises of treasure, memories of the prestige of Quraysh and straight bribes.[39]

Muhammad's policy in the next two years after the battle of Uhud was to prevent as best he could the formation of alliances against him. Whenever alliances of tribesmen against Medina were formed, he sent out an expedition to break it up.[39] When Muhammad heard of men massing with hostile intentions against Medina, he reacted with severity.[40] One example is the assassination of Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf, a member of the Jewish tribe of Banu Nadir who had gone to Mecca and written poems that had helped rouse the Meccans' grief, anger and desire for revenge after the battle of Badr (see the main article for other reasons for killing of Ka'b given in the historiographical sources).[41] Around a year later, Muhammad expelled the Jewish Banu Nadir from Medina.[42]

Muhammad's attempts to prevent formation of confederation against him were not successful, although he was able to augment his own forces and keep many tribes from joining the confederation.[43]

Siege of Medina

Abu Sufyan, the military leader of the Quraysh, with the help of Banu Nadir, the exiled Jewish tribe from Medina, had mustered a force of numbering 10,000 men. Muhammad was able to prepare a force of about 3,000 men. He had however adopted a new form of defense, unknown in Arabia at that time: Muslims had dug trenches wherever Medina lay open to cavalry attack. The idea is credited to a Persian convert to Islam, Salman. The siege of Medina began on 31 March 627 and lasted for two weeks.[44] Abu Sufyan's troops were unprepared for the fortifications they were confronted with, and after an ineffectual siege, the coalition decided to go home.[45] The Qur'an discusses this battle in verses 9-27 of sura 33, Al-Ahzab.[46][47]

During the Battle of the Trench, the Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza who were located at the south of Medina were charged with treachery. After the retreat of the coalition, Muslims besieged Banu Qurayza, the remaining major Jewish tribe in Medina. The Banu Qurayza surrendered and all the men, apart from a few who converted to Islam, were beheaded, while all the women and children were enslaved.[48][49] In dealing with Muhammad's treatment of the Jews of Medina, aside from political explanations, Arab historians and biographers have explained it as "the punishment of the Medina Jews, who were invited to convert and refused, perfectly exemplify the Quran's tales of what happened to those who rejected the prophets of old."[50] F.E. Peters, a western scholar of Islam, states that Muhammad's treatment of Jews of Medina was essentially political being prompted by what Muhammad read as treasonous and not some transgression of the law of God.[26] Peters adds that Muhammad was possibly emboldened by his military successes and also wanted to push his advantage. Economical motivations according to Peters also existed since the poorness of the Meccan migrants was a source of concern for Muhammad.[51] Peters argues that Muhammad's treatment of the Jews of Medina was "quite extraordinary", "matched by nothing in the Qur'an", and is "quite at odds with Muhammad's treatment of the Jews he encountered outside Medina."[26] According to Welch, Muhammad's treatment of the three major Jewish tribes brought Muhammad closer to his goal of organizing a community strictly on a religious basis. He adds that some Jews from other families were, however, allowed to remain in Medina.[3]

In the siege of Medina, the Meccans had exerted their utmost strength towards the destruction of the Muslim community. Their failure resulted in a significant loss of prestige; their trade with Syria was gone.[52] Following the battle of trench, Muhammad made two expeditions to the north which ended without any fighting.[3] While returning from one of these two expeditions (or some years earlier according to other early accounts), an accusation of adultery was made against Aisha, Muhammad's wife. Aisha was exonerated from the accusations when Muhammad announced that he had received a revelation, verse4 in the An-Nur sura,[53] confirming Aisha's innocence and directing that charges of adultery be supported by four eyewitnesses.[54]

Truce of Hudaybiyya

Although Qur'anic verses had been received from God commanding the Hajj,[55] the Muslims had not performed it due to the enmity of the Quraysh. In the month of Shawwal 628, Muhammad ordered his followers to obtain sacrificial animals and to make preparations for a pilgrimage (umrah) to Mecca, saying that God had promised him the fulfillment of this goal in a vision where he was shaving his head after the completion of the Hajj.[56] According to Lewis, Muhammad felt strong enough to attempt an attack on Mecca, but on the way it became clear that the attempt was premature and the expedition was converted into a peaceful pilgrimage.[57] Andrae disagrees, writing that the Muslim state of ihram (which restricted their freedom of action) and the paucity of arms carried indicated that the pilgrimage was always intended to be pacific. Most Islamic scholars agree to Andrae's view.[58] Upon hearing of the approaching 1,400 Muslims, the Quraysh sent out a force of 200 cavalry to halt them. Muhammad evaded them by taking a more difficult route, thereby reaching al-Hudaybiyya, just outside Mecca.[59] According to Watt, although Muhammad's decision to make the pilgrimage was based on his dream, he was at the same time demonstrating to the pagan Meccans that Islam does not threaten the prestige of their sanctuary, and that Islam was an Arabian religion.[60]

Negotiations commenced with emissaries going to and from Mecca. While these continued, rumors spread that one of the Muslim negotiators, Uthman ibn Affan, had been killed by the Quraysh. Muhammad responded by calling upon the pilgrims to make a pledge not to flee (or to stick with Muhammad, whatever decision he made) if the situation descended into war with Mecca. This pledge became known as the "Pledge of Good Pleasure" (Arabic: بيعة الرضوان, bay'at al-ridhwān) or the "Pledge of the Tree." News of Uthman's safety, however, allowed for negotiations to continue, and the treaty of Hudaybiyyah, scheduled to last ten years was eventually signed between the Muslims and the Quraysh.[57][59] The main points of treaty were the following:

- The two parties and their allies should desist from hostilities against each other.[61]

- Muhammad, should not perform Hajj this year but in the next year, Mecca will be evacuated for three days for Muslims to perform Hajj.[62]

- Muhammad should send back any Meccan who had gone to Medina without the permission of his or her protector (according to William Montgomery Watt, this presumably refers to minors or women).[62]

- It was allowed for both Muhammad and the Quraysh to enter into alliance with others.[62]

Many Muslims were not satisfied with the terms of the treaty. However, the Qur'anic sura Al-Fath (The Victory)[63] assured the Muslims that the expedition from which they were now returning must be considered a victorious one.[64] It was only later that Muhammad's followers would realise the benefit behind this treaty. These benefits, according to Welch, included the inducing of the Meccans to recognise Muhammad as an equal; a cessation of military activity posing well for the future; and gaining the admiration of Meccans who were impressed by the incorporation of the pilgrimage rituals.[3]

After signing the truce, Muhammad made an expedition against the Jewish oasis of Khaybar. The explanation given by western scholars of Islam for this attack ranges from the presence of the Banu Nadir in Khaybar, who were inciting hostilities along with neighboring Arab tribes against Muhammad, to deflecting from what appeared to some Muslims as the inconclusive result of the truce of Hudaybiyya, increasing Muhammad's prestige among his followers and capturing booty.[30][65] According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad also sent letters to many rulers of the world, asking them to convert to Islam (the exact date are given variously in the sources).[3][66][67] Hence he sent messengers (with letters) to Heraclius of the Byzantine Empire (the eastern Roman Empire), Khosrau of Persia, the chief of Yemen and to some others.[66][67] Most critical scholars doubt this tradition, however.[68] In the years following the truce of Hudaybiyya, Muhammad sent his forces against the Arabs of Mu'tah on Byzantine soil in Transjordania since according to the tradition, they had murdered Muhammad's envoy." Muslims scored victory in this battle.[69]

Conquest of Mecca

The truce of Hudaybiyya had been enforced for two years.[70][71] The tribe of Khuz'aah had a friendly relationship with Muhammad, while on the other hand their enemies, the Banu Bakr, had an alliance with the Meccans.[70][71] A clan of the Bakr made a night raid against the Khuz'aah, killing a few of them.[70][71] The Meccans helped their allies (i.e., the Banu Bakr) with weapons and, according to some sources, a few Meccans also took part in the fighting.[70] After this event, Muhammad sent a message to Mecca with three conditions, asking them to accept one of them. These were the following[72]

- The Meccans were to pay blood money for those slain among the Khuza'ah tribe, or

- They should have nothing to do with the Banu Bakr, or

- They should declare the truce of Hudaybiyya null.

The Meccans replied that they would accept only the third condition.[72] However, soon they realized their mistake and sent Abu Safyan to renew the Hudaybiyya treaty, but now his request was declined by Muhammad. Muhammad began to prepare for a campaign.[73]

In 630, Muhammad marched on Mecca with an enormous force, said to number more than ten thousand men. With minimal casualties, Muhammad took control of Mecca.[74] He declared an amnesty for past offences, except for ten men and women who had mocked and made fun of him in songs and verses. Some of these were later pardoned.[75] Most Meccans converted to Islam, and Muhammad subsequently destroyed all of the statues of Arabian gods in and around the Kaaba, without any exception.[76][77] The Qur'an discusses the conquest of Mecca in verses 1-3 of the An-Nasrsura.[47][78]

Conquest of Arabia

Soon after the conquest of Mecca, Muhammad was alarmed by a military threat from the confederate tribes of Hawazin who were collecting an army twice the size of Muhammad's. The Hawzain were old enemies of Meccans. They were joined by the tribe of Banu Thaqif inhabiting in the city of Ta’if who had adopted an anti-Meccan policy due to the decline of the prestige of Meccans.[79] Muhammad defeated the Hawzain and Thaqif in the battle of Hunayn.[3]

In the same year, Muhammad launched an expedition against northern Arabia, the battle of Tabouk, because of their previous defeat at the battle of Mu'tah, as well as the reports of the hostile attitude adopted against Muslims. Although Muhammad did not make contact with hostile forces at Tabuk, he received the submission of some of the local chiefs of the region.[3][81] A year after the battle of Tabuk, the tribe of Thaqif, inhabiting in the city of Ta’if, sent emissaries to Medina to surrender to Muhammad and adopt Islam. Many Bedouins submitted to Muhammad in order to be safe from attack and to benefit from the bounty of the wars.[3] The Bedouins however were alien to the system of Islam and wanted to maintain their independence, their established code of virtue and their ancestral traditions. Consequently, Muhammad demanded of them a military and political agreement according to which they "acknowledge the suzerainty of Medina, [promise] to refrain from attacking the Muslims and their allies, and to pay the Zakat, the Muslim religious levy."[82]

Farewell Pilgrimage

At the end of the tenth year after the migration to Medina, Muhammad performed his first truly Islamic pilgrimage, thereby teaching his followers the rules governing the various ceremonies of the annual Great Pilgrimage (hajj). On this occasion, he uttered the Quranic verse:[3]

This day have I perfected your religion for you, completed My favour upon you, and have chosen for you Islam as your religion.

Death

A few months after the farewell pilgrimage, Muhammad fell ill and suffered for several days with head pain and weakness. He died on Monday, June 8, 632, in the city of Medina. His tomb had previously been the home of his wife Aisha. It is now enclosed within Al-Masjid al-Nabawi (Mosque of the Prophet) in Medina.[3][84]

See also

- Muslim history

- Timeline of Muslim history

Notes

- The Cambridge History of Islam (1977), p. 39

- Esposito (1998), p. 17.

- Alford Welch, Muhammad, Encyclopedia of Islam

- Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shi'i Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shiʻism, Yale University Press, p. 5

- Fazlur Rahman (1979), p. 21

- See:

- Esposito (1998), p.17

- Neusner (2003), p.153

- Watt (1956), p. 175, p. 177.

- Norman Stillman, Yahud, Encyclopedia of Islam

- Lewis, "The Arabs in History," 2003, p. 44.

- Montgomery Watt, Muhammad, Prophet and Statesman, Oxford University Press, 1961, p. 105.

- Quran 22:39–40

- John Kelsay, Islam and War: A Study in Comparative Ethics, p. 21

- Watt, Muhammad, Prophet and Statesman, Oxford University Press, 1961, p. 105, 107

- Bernard Lewis (1993), p. 41.

- Rodinson (2002), p. 164.

- The Cambridge History of Islam, p. 45

- Glubb (2002), pp. 179–186.

- Watt (1961), pp. 122–3.

- Watt (1961), p. 123.

- Rodinson(2002), pp. 168–9.

- Lewis, "The Arabs in History," p. 44.

- Watt (1956), p. 179.

- Endress (2003), p. 29

- The Cambridge History of Islam (1977), pp. 43–44

- Cohen (1995), p. 23

- Francis Edward Peters (2003), p. 194.

- Watt (1961), p. 132.

- Watt (1964), pp. 124–125

- Watt (1961), p. 134

- Lewis (1960), p. 45.

- Rodinson (2002), pp. 177, 180.

- "Uhud", Encyclopedia of Islam.

- Watt (1964) p. 137

- Watt (1974) p. 137

- Watt (1974) p. 141

- Rodinson (2002), p. 183.

- Quran 3:133-135, Quran 3:160-162

- Watt (1964) p. 144.

- Watt (1956), p. 30.

- Watt (1956), p. 34

- Watt (1956), p. 18

- Watt (1956), pp. 220–221

- Watt (1956), p. 35

- Watt (1956), p. 36, 37

- Rodinson (2002), pp. 209–211.

- Quran 33:9–27

- Uri Rubin, Quraysh, Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an

- Peterson, Muhammad: the prophet of God, p. 126

- Tariq Ramadan, In the Footsteps of the Prophet, Oxford University Press, p. 141

- Francis Edward Peters (2003), p. 77

- F.E.Peters (2003), pp. 76–8.

- Watt (1956), p. 39

- Quran 24:4

- Watt, M. "Aisha bint Abi Bakr". In P.J. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

- Quran 2:196–210

- Lings (1987), p. 249

- Lewis (2002), p. 42.

- Andrae; Menzel (1960) p. 156; See also: Watt (1964) p. 183

- "al-Hudaybiya", Encyclopedia of Islam

- Watt, W. Montgomery. "al- Hudaybiya or al-Hudaybiyya." Encyclopaedia of Islam.

- Lings (1987), p. 253

- Watt, al- Ḥudaybiya or al-Hudaybiyya, Encyclopaedia of Islam

- Quran 48:1-29

- Lings (1987), p. 255

- Veccia Vaglieri, L. "Khaybar", Encyclopaedia of Islam

- Lings (1987), p. 260

- Khan (1998), pp. 250–251

- Gabriel Said Reynolds, The Emergence of Islam (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2012), p. 49.

- F. Buhl, Muta, Encyclopedia of Islam

- Khan (1998), p. 274

- Lings (1987), p. 291

- Khan (1998), pp. 274–5.

- Lings (1987), p. 292

- Watt (1956), p. 66.

- Rodinson (2002), p. 261.

- Harold Wayne Ballard, Donald N. Penny, W. Glenn Jonas, A Journey of Faith: An Introduction to Christianity, Mercer University Press, p.163

- F. E. Peters, Islam, a Guide for Jews and Christians, Princeton University Press, p.240

- Quran 110:1–3

- Watt, Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman, Oxford University Press, p.207

- Ali, Wijdan. "From the Literal to the Spiritual: The Development of Muhammad's Portrayal from 13th century Ilkhanid Miniatures to 17th century Ottoman Art Archived 2004-12-03 at the Wayback Machine". In Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Turkish Art, eds. M. Kiel, N. Landman, and H. Theunissen. No. 7, 1–24. Utrecht, The Netherlands, August 23–28, 1999, p. 7

- M.A. al-Bakhit, Tabuk, Encyclopedia of Islam

- Bernard Lewis, The Arabs in History, Oxford University Press, 1993, p.43-44

- Quran 5:3

- Leila Ahmed (Summer 1986). "Women and the Advent of Islam". Signs. 11 (4): 665–91 (686). doi:10.1086/494271. ISSN 0097-9740. JSTOR 3174138.