Beowulf

Beowulf (/ˈbeɪəwʊlf/;[2] Old English: Bēowulf [ˈbeːowulf]) is an Old English epic poem consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important works of Old English literature. The date of composition is a matter of contention among scholars; the only certain dating pertains to the manuscript, which was produced between 975 and 1025.[3] The anonymous poet is referred to by scholars as the "Beowulf poet".[4]

| Beowulf | |

|---|---|

| Bēowulf | |

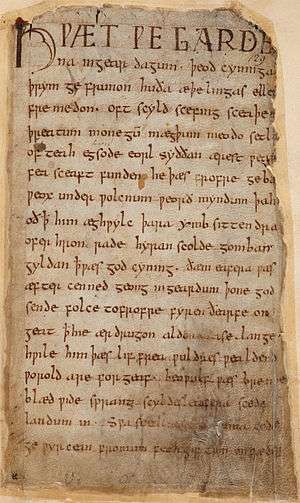

First page of Beowulf in Cotton Vitellius A. xv | |

| Author(s) | Unknown |

| Language | West Saxon dialect of Old English |

| Date | disputed (c. 700–1000 AD) |

| State of existence | Manuscript suffered damage from fire in 1731 |

| Manuscript(s) | Cotton Vitellius A. xv (c. 975–1010 AD)[1] |

| First printed edition | Thorkelin (1815) |

| Genre | Epic heroic writing |

| Verse form | Alliterative verse |

| Length | c. 3182 lines |

| Subject | The battles of Beowulf, the Geatish hero, in youth and old age |

| Personages | Beowulf, Hygelac, Hrothgar, Wealhþeow, Hrothulf, Æschere, Unferth, Grendel, Grendel's mother, Wiglaf, Hildeburh. |

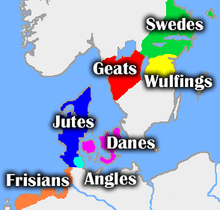

The story is set in Scandinavia in the 6th century. Beowulf, a hero of the Geats, comes to the aid of Hrothgar, the king of the Danes, whose mead hall in Heorot has been under attack by a monster known as Grendel. After Beowulf slays him, Grendel's mother attacks the hall and is then also defeated. Victorious, Beowulf goes home to Geatland (Götaland in modern Sweden) and becomes king of the Geats. Fifty years later, Beowulf defeats a dragon, but is mortally wounded in the battle. After his death, his attendants cremate his body and erect a tower on a headland in his memory.

The poem survives in a single copy in the manuscript known as the Nowell Codex. It has no title in the original manuscript, but has become known by the name of the story's protagonist.[5] In 1731, the manuscript was damaged by a fire that swept through Ashburnham House in London that had a collection of medieval manuscripts assembled by Sir Robert Bruce Cotton; the margins were charred, and a number of readings were lost.[6] The Nowell Codex is housed in the British Library.

Historical background

The events in the poem take place over most of the sixth century, and feature no English characters. Some suggest that Beowulf was first composed in the 7th century at Rendlesham in East Anglia, as the Sutton Hoo ship-burial shows close connections with Scandinavia, and the East Anglian royal dynasty, the Wuffingas, may have been descendants of the Geatish Wulfings.[7][8] Others have associated this poem with the court of King Alfred the Great or with the court of King Cnut the Great.[9]

The poem blends fictional, legendary and historic elements. Although Beowulf himself is not mentioned in any other Anglo-Saxon manuscript,[10] scholars generally agree that many of the other figures referred to in Beowulf also appear in Scandinavian sources (specific works are designated in the section titled "Sources and analogues").[11] This concerns not only individuals (e.g., Healfdene, Hroðgar, Halga, Hroðulf, Eadgils and Ohthere), but also clans (e.g., Scyldings, Scylfings and Wulfings) and certain events (e.g., the battle between Eadgils and Onela). The raid by King Hygelac into Frisia is mentioned by Gregory of Tours in his History of the Franks and can be dated to around 521.[12]

In Denmark, recent archaeological excavations at Lejre, where Scandinavian tradition located the seat of the Scyldings, i.e., Heorot, have revealed that a hall was built in the mid-6th century, exactly the time period of Beowulf.[13] Three halls, each about 50 metres (160 ft) long, were found during the excavation.[13]

The majority view appears to be that people such as King Hroðgar and the Scyldings in Beowulf are based on historical people from 6th-century Scandinavia.[14] Like the Finnesburg Fragment and several shorter surviving poems, Beowulf has consequently been used as a source of information about Scandinavian figures such as Eadgils and Hygelac, and about continental Germanic figures such as Offa, king of the continental Angles.

19th-century archaeological evidence may confirm elements of the Beowulf story. Eadgils was buried at Uppsala (Gamla Uppsala, Sweden) according to Snorri Sturluson. When the western mound (to the left in the photo) was excavated in 1874, the finds showed that a powerful man was buried in a large barrow, c. 575, on a bear skin with two dogs and rich grave offerings. The eastern mound was excavated in 1854, and contained the remains of a woman, or a woman and a young man. The middle barrow has not been excavated.[16][15]

Summary

The protagonist Beowulf, a hero of the Geats, comes to the aid of Hrothgar, king of the Danes, whose great hall, Heorot, is plagued by the monster Grendel. Beowulf kills Grendel with his bare hands and Grendel's mother with a giant's sword that he found in her lair.

Later in his life, Beowulf becomes king of the Geats, and finds his realm terrorized by a dragon, some of whose treasure had been stolen from his hoard in a burial mound. He attacks the dragon with the help of his thegns or servants, but they do not succeed. Beowulf decides to follow the dragon to its lair at Earnanæs, but only his young Swedish relative Wiglaf, whose name means "remnant of valour",[lower-alpha 1] dares to join him. Beowulf finally slays the dragon, but is mortally wounded in the struggle. He is cremated and a burial mound by the sea is erected in his honour.

Beowulf is considered an epic poem in that the main character is a hero who travels great distances to prove his strength at impossible odds against supernatural demons and beasts. The poem also begins in medias res or simply, "in the middle of things," which is a characteristic of the epics of antiquity. Although the poem begins with Beowulf's arrival, Grendel's attacks have been an ongoing event. An elaborate history of characters and their lineages is spoken of, as well as their interactions with each other, debts owed and repaid, and deeds of valour. The warriors form a kind of brotherhood linked by loyalty to their lord. The poem begins and ends with funerals: at the beginning of the poem for Scyld Scefing (26–45) and at the end for Beowulf (3140–3170).

First battle: Grendel

Beowulf begins with the story of Hrothgar, who constructed the great hall Heorot for himself and his warriors. In it, he, his wife Wealhtheow, and his warriors spend their time singing and celebrating. Grendel, a troll-like monster said to be descended from the biblical Cain, is pained by the sounds of joy.[19] Grendel attacks the hall and kills and devours many of Hrothgar's warriors while they sleep. Hrothgar and his people, helpless against Grendel, abandon Heorot.

Beowulf, a young warrior from Geatland, hears of Hrothgar's troubles and with his king's permission leaves his homeland to assist Hrothgar.[20]

Beowulf and his men spend the night in Heorot. Beowulf refuses to use any weapon because he holds himself to be the equal of Grendel.[21] When Grendel enters the hall, Beowulf, who has been feigning sleep, leaps up to clench Grendel's hand.[22] Grendel and Beowulf battle each other violently.[23] Beowulf's retainers draw their swords and rush to his aid, but their blades cannot pierce Grendel's skin.[24] Finally, Beowulf tears Grendel's arm from his body at the shoulder and Grendel runs to his home in the marshes where he dies.[25] Beowulf displays "the whole of Grendel's shoulder and arm, his awesome grasp" for all to see at Heorot. This display would fuel Grendel's mother's anger in revenge.[26]

Second battle: Grendel's mother

The next night, after celebrating Grendel's defeat, Hrothgar and his men sleep in Heorot. Grendel's mother, angry that her son has been killed, sets out to get revenge. "Beowulf was elsewhere. Earlier, after the award of treasure, The Geat had been given another lodging"; his assistance would be absent in this battle.[27] Grendel's mother violently kills Æschere, who is Hrothgar's most loyal fighter, and escapes.

Hrothgar, Beowulf, and their men track Grendel's mother to her lair under a lake. Unferð, a warrior who had earlier challenged him, presents Beowulf with his sword Hrunting. After stipulating a number of conditions to Hrothgar in case of his death (including the taking in of his kinsmen and the inheritance by Unferth of Beowulf's estate), Beowulf jumps into the lake, and while harassed by water monsters gets to the bottom, where he finds a cavern. Grendel's mother pulls him in, and she and Beowulf engage in fierce combat.

At first, Grendel's mother appears to prevail, and Hrunting proves incapable of hurting the woman; she throws Beowulf to the ground and, sitting astride him, tries to kill him with a short sword, but Beowulf is saved by his armour. Beowulf spots another sword, hanging on the wall and apparently made for giants, and cuts her head off with it. Travelling further into Grendel's mother's lair, Beowulf discovers Grendel's corpse and severs his head with the sword, whose blade melts because of the "hot blood". Only the hilt remains. Beowulf swims back up to the rim of the pond where his men wait. Carrying the hilt of the sword and Grendel's head, he presents them to Hrothgar upon his return to Heorot. Hrothgar gives Beowulf many gifts, including the sword Nægling, his family's heirloom. The events prompt a long reflection by the king, sometimes referred to as "Hrothgar's sermon", in which he urges Beowulf to be wary of pride and to reward his thegns.[28]

Third battle: The dragon

Beowulf returns home and eventually becomes king of his own people. One day, fifty years after Beowulf's battle with Grendel's mother, a slave steals a golden cup from the lair of a dragon at Earnanæs. When the dragon sees that the cup has been stolen, it leaves its cave in a rage, burning everything in sight. Beowulf and his warriors come to fight the dragon, but Beowulf tells his men that he will fight the dragon alone and that they should wait on the barrow. Beowulf descends to do battle with the dragon, but finds himself outmatched. His men, upon seeing this and fearing for their lives, retreat into the woods. One of his men, Wiglaf, however, in great distress at Beowulf's plight, comes to his aid. The two slay the dragon, but Beowulf is mortally wounded. After Beowulf dies, Wiglaf remains by his side, grief-stricken. When the rest of the men finally return, Wiglaf bitterly admonishes them, blaming their cowardice for Beowulf's death. Afterward, Beowulf is ritually burned on a great pyre in Geatland while his people wail and mourn him, fearing that without him, the Geats are defenceless against attacks from surrounding tribes. Afterwards, a barrow, visible from the sea, is built in his memory (Beowulf lines 2712–3182).[29]

Authorship and date

The dating of Beowulf has attracted considerable scholarly attention and opinion differs as to whether it was first written in the 8th century or whether the composition of the poem was nearly contemporary with its eleventh century manuscript and whether a proto-version of the poem (possibly a version of the Bear's Son Tale) was orally transmitted before being transcribed in its present form. Albert Lord felt strongly that the manuscript represents the transcription of a performance, though likely taken at more than one sitting.[30] J. R. R. Tolkien believed that the poem retains too genuine a memory of Anglo-Saxon paganism to have been composed more than a few generations after the completion of the Christianisation of England around AD 700,[31] and Tolkien's conviction that the poem dates to the 8th century has been defended by Tom Shippey, Leonard Neidorf, Rafael J. Pascual, and R.D. Fulk, among others.[32][33][34] An analysis of several Old English poems by a team including Neidorf suggests that Beowulf is the work of a single author.[35]

The claim to an early 11th-century date depends in part on scholars who argue that, rather than the transcription of a tale from the oral tradition by an earlier literate monk, Beowulf reflects an original interpretation of an earlier version of the story by the manuscript's two scribes. On the other hand, some scholars argue that linguistic, palaeographical, metrical, and onomastic considerations align to support a date of composition in the first half of the eighth century;[36][37][38][39] in particular, the poem's apparent observation of etymological vowel-length distinctions in unstressed syllables (described by Kaluza's law) has been thought to demonstrate a date of composition prior to the earlier ninth century.[33][34] However, scholars disagree about whether the metrical phenomena described by Kaluza's Law prove an early date of composition or are evidence of a longer prehistory of the Beowulf meter;[40] B.R. Hutcheson, for instance, does not believe Kaluza's Law can be used to date the poem, while claiming that "the weight of all the evidence Fulk presents in his book[lower-alpha 2] tells strongly in favour of an eighth-century date."[41]

From an analysis of creative genealogy and ethnicity, Craig R. Davis suggests a composition date in the AD 890s, when King Alfred of England had secured the submission of Guthrum, leader of a division of the Great Heathen Army of the Danes, and of Aethelred, ealdorman of Mercia. In this thesis, the trend of appropriating Gothic royal ancestry, established in Francia during Charlemagne's reign, influenced the Anglian kingdoms of Britain to attribute to themselves a Geatish descent. The composition of Beowulf was the fruit of the later adaptation of this trend in Alfred's policy of asserting authority over the Angelcynn, in which Scyldic descent also was attributed to the West-Saxon royal pedigree. This date of composition largely agrees with Lapidge's positing of a West-Saxon exemplar c.900.[42]

Manuscript

Beowulf survives in a single parchment manuscript dated on palaeographical grounds to the late 10th or early 11th century. The manuscript measures 245 × 185 mm.[43]

Provenance

The poem is known only from a single manuscript, which is estimated to date from around 975–1025, in which it appears with other works.[3] The manuscript therefore dates either to the reign of Æthelred the Unready, characterised by strife with the Danish king Sweyn Forkbeard, or to the beginning of the reign of Sweyn's son Cnut the Great from 1016. The Beowulf manuscript is known as the Nowell Codex, gaining its name from 16th-century scholar Laurence Nowell. The official designation is "British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.XV" because it was one of Sir Robert Bruce Cotton's holdings in the Cotton library in the middle of the 17th century. Many private antiquarians and book collectors, such as Sir Robert Cotton, used their own library classification systems. "Cotton Vitellius A.XV" translates as: the 15th book from the left on shelf A (the top shelf) of the bookcase with the bust of Roman Emperor Vitellius standing on top of it, in Cotton's collection. Kevin Kiernan argues that Nowell most likely acquired it through William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, in 1563, when Nowell entered Cecil's household as a tutor to his ward, Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford.[44]

The earliest extant reference to the first foliation of the Nowell Codex was made sometime between 1628 and 1650 by Franciscus Junius (the younger).[45]:91 The ownership of the codex before Nowell remains a mystery.[45]:120

The Reverend Thomas Smith (1638–1710) and Humfrey Wanley (1672–1726) both catalogued the Cotton library (in which the Nowell Codex was held). Smith's catalogue appeared in 1696, and Wanley's in 1705.[46] The Beowulf manuscript itself is identified by name for the first time in an exchange of letters in 1700 between George Hickes, Wanley's assistant, and Wanley. In the letter to Wanley, Hickes responds to an apparent charge against Smith, made by Wanley, that Smith had failed to mention the Beowulf script when cataloguing Cotton MS. Vitellius A. XV. Hickes replies to Wanley "I can find nothing yet of Beowulph."[47] Kiernan theorised that Smith failed to mention the Beowulf manuscript because of his reliance on previous catalogues or because either he had no idea how to describe it or because it was temporarily out of the codex.[48]

It suffered damage in the Cotton Library fire at Ashburnham House in 1731. Since then, parts of the manuscript have crumbled along with many of the letters. Rebinding efforts, though saving the manuscript from much degeneration, have nonetheless covered up other letters of the poem, causing further loss. Kevin Kiernan, in preparing his electronic edition of the manuscript, used fibre-optic backlighting and ultraviolet lighting to reveal letters in the manuscript lost from binding, erasure, or ink blotting.[49]

Writing

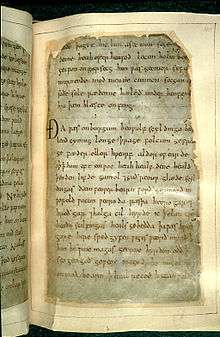

The Beowulf manuscript was transcribed from an original by two scribes, one of whom wrote the prose at the beginning of the manuscript and the first 1939 lines before breaking off in mid sentence. The first scribe made a point of carefully regularizing the spelling of the original document by using the common West Saxon language and by avoiding any archaic or dialectical features. The second scribe, who wrote the remainder, with a difference in handwriting noticeable after line 1939, seems to have written more vigorously and with less interest. As a result, the second scribe's script retains more archaic dialectic features, which allow modern scholars to ascribe the poem a cultural context.[50] While both scribes appear to have proofread their work, there are nevertheless many errors.[51] The second scribe was ultimately the more conservative copyist as he did not modify the spelling of the text as he wrote but copied what he saw in front of him. In the way that it is currently bound, the Beowulf manuscript is followed by the Old English poem Judith. Judith was written by the same scribe that completed Beowulf as evidenced through similar writing style. Wormholes found in the last leaves of the Beowulf manuscript that are absent in the Judith manuscript suggest that at one point Beowulf ended the volume. The rubbed appearance of some leaves also suggest that the manuscript stood on a shelf unbound, as is known to have been the case with other Old English manuscripts.[50] From knowledge of books held in the library at Malmesbury Abbey and available as source works, as well as from the identification of certain words particular to the local dialect found in the text, the transcription may have taken place there.[52]

Debate over oral tradition

The question of whether Beowulf was passed down through oral tradition prior to its present manuscript form has been the subject of much debate, and involves more than simply the issue of its composition. Rather, given the implications of the theory of oral-formulaic composition and oral tradition, the question concerns how the poem is to be understood, and what sorts of interpretations are legitimate.

Scholarly discussion about Beowulf in the context of the oral tradition was extremely active throughout the 1960s and 1970s. The debate might be framed starkly as follows: on the one hand, we can hypothesise a poem put together from various tales concerning the hero (the Grendel episode, the story of Grendel's mother, and the fire drake narrative). These fragments would have been told for many years in tradition, and learned by apprenticeship from one generation of illiterate poets to the next. The poem is composed orally and extemporaneously, and the archive of tradition on which it draws is oral, pagan, Germanic, heroic, and tribal. On the other hand, one might posit a poem which is composed by a literate scribe, who acquired literacy by way of learning Latin (and absorbing Latinate culture and ways of thinking), probably a monk and therefore profoundly Christian in outlook. On this view, the pagan references would be a sort of decorative archaising.[53][54] There is a third view that sees merit in both arguments above and attempts to bridge them, and so cannot be articulated as starkly as they can; it sees more than one Christianity and more than one attitude towards paganism at work in the poem; it sees the poem as initially the product of a literate Christian author with one foot in the pagan world and one in the Christian, himself perhaps a convert (or one whose forebears had been pagan), a poet who was conversant in both oral and literary composition and was capable of a masterful "repurposing" of poetry from the oral tradition.

However, scholars such as D.K. Crowne have proposed the idea that the poem was passed down from reciter to reciter under the theory of oral-formulaic composition, which hypothesises that epic poems were (at least to some extent) improvised by whoever was reciting them, and only much later written down. In his landmark work, The Singer of Tales, Albert Lord refers to the work of Francis Peabody Magoun and others, saying "the documentation is complete, thorough, and accurate. This exhaustive analysis is in itself sufficient to prove that Beowulf was composed orally."[55]

Examination of Beowulf and other Old English literature for evidence of oral-formulaic composition has met with mixed response. While "themes" (inherited narrative subunits for representing familiar classes of event, such as the "arming the hero",[56] or the particularly well-studied "hero on the beach" theme[57]) do exist across Anglo-Saxon and other Germanic works, some scholars conclude that Anglo-Saxon poetry is a mix of oral-formulaic and literate patterns, arguing that the poems both were composed on a word-by-word basis and followed larger formulae and patterns.[58]

Larry Benson argued that the interpretation of Beowulf as an entirely formulaic work diminishes the ability of the reader to analyse the poem in a unified manner, and with due attention to the poet's creativity. Instead, he proposed that other pieces of Germanic literature contain "kernels of tradition" from which Beowulf borrows and expands upon.[59][60] A few years later, Ann Watts argued against the imperfect application of one theory to two different traditions: traditional, Homeric, oral-formulaic poetry and Anglo-Saxon poetry.[60][61] Thomas Gardner agreed with Watts, arguing that the Beowulf text is of too varied a nature to be completely constructed from set formulae and themes.[60][62]

John Miles Foley wrote, referring to the Beowulf debate,[63] that while comparative work was both necessary and valid, it must be conducted with a view to the particularities of a given tradition; Foley argued with a view to developments of oral traditional theory that do not assume, or depend upon, ultimately unverifiable assumptions about composition, and instead delineate a more fluid continuum of traditionality and textuality.[64][65][66][56]

Finally, in the view of Ursula Schaefer, the question of whether the poem was "oral" or "literate" becomes something of a red herring.[67] In this model, the poem is created, and is interpretable, within both noetic horizons. Schaefer's concept of "vocality" offers neither a compromise nor a synthesis of the views which see the poem as on the one hand Germanic, pagan, and oral and on the other Latin-derived, Christian, and literate, but, as stated by Monika Otter: "... a 'tertium quid', a modality that participates in both oral and literate culture yet also has a logic and aesthetic of its own."[68]

Transcriptions and translations

Transcriptions

Icelandic scholar Grímur Jónsson Thorkelin made the first transcriptions of the manuscript in 1786 and published the results in 1815, working as part of a Danish government historical research commission. He made one himself, and had another done by a professional copyist who knew no Anglo-Saxon. Since that time, however, the manuscript has crumbled further, making these transcripts a prized witness to the text. While the recovery of at least 2000 letters can be attributed to them, their accuracy has been called into question,[lower-alpha 3] and the extent to which the manuscript was actually more readable in Thorkelin's time is uncertain.

Translations and adaptations

A great number of translations and adaptations are available, in poetry and prose. Andy Orchard, in A Critical Companion to Beowulf, lists 33 "representative" translations in his bibliography,[70] while the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies published Marijane Osborn's annotated list of over 300 translations and adaptations in 2003.[71] Beowulf has been translated into at least 23 other languages.[72]

19th century

In 1805, the historian Sharon Turner translated selected verses into modern English.[73] This was followed in 1814 by John Josias Conybeare who published an edition "in English paraphrase and Latin verse translation."[73] In 1815, Grímur Jónsson Thorkelin published the first complete edition in Latin.[73] N. F. S. Grundtvig reviewed this edition in 1815 and created the first complete verse translation in Danish in 1820.[73] In 1837, John Mitchell Kemble created an important literal translation in English.[73] In 1895, William Morris & A. J. Wyatt published the ninth English translation.[73] Many retellings of Beowulf for children began appearing in the 20th century.[74]

20th century

In 1909, Francis Barton Gummere's full translation in "English imitative meter" was published,[73] and was used as the text of Gareth Hinds's graphic novel based on Beowulf in 2007.

First published in 1928, Frederick Klaeber's Beowulf and The Fight at Finnsburg[75] (which included the poem in Old English, an extensive glossary of Old English terms, and general background information) became the "central source used by graduate students for the study of the poem and by scholars and teachers as the basis of their translations."[76]

Seamus Heaney's 1999 translation of the poem (referred to by Howell Chickering and many others as "Heaneywulf"[77]) was both praised and criticized. The US publication was commissioned by W. W. Norton & Company, and was included in the Norton Anthology of English Literature.

21st century

R. D. Fulk, of Indiana University, published the first facing-page edition and translation of the entire Nowell Codex manuscript in the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library series in 2010.[78]

Following research in the King's College London Archives, Carl Kears proposed that John Porter's translation, published in 1975 by Bill Griffiths' Pirate Press, was the first complete verse translation of the poem entirely accompanied by facing-page Old English.[79]

Translating Beowulf is one of the subjects of the 2012 publication Beowulf at Kalamazoo, containing a section with 10 essays on translation, and a section with 22 reviews of Heaney's translation (some of which compare Heaney's work with that of Anglo-Saxon scholar Roy Liuzza).[80]

J. R. R. Tolkien's long-awaited translation (edited by his son, Christopher) was published in 2014 as Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary.[81][82] This also includes Tolkien's own retelling of the story of Beowulf in his tale, Sellic Spell.

The Mere Wife, by Maria Dahvana Headley, was published in 2018. It relocates the action to a wealthy community in 20th century America and is told primarily from the point of view of Grendel's mother.[83]

Sources and analogues

Neither identified sources nor analogues for Beowulf can be definitively proven, but many conjectures have been made. These are important in helping historians understand the Beowulf manuscript, as possible source-texts or influences would suggest time-frames of composition, geographic boundaries within which it could be composed, or range (both spatial and temporal) of influence (i.e. when it was "popular" and where its "popularity" took it).

There are Scandinavian sources, international folkloric sources, and Celtic sources.[lower-alpha 4][84]

Scandinavian parallels and sources

19th century studies proposed that Beowulf was translated from a lost original Scandinavian work, but this idea was quickly abandoned. But Scandinavian works have continued to be studied as a possible source.[85] Proponents included Gregor Sarrazin writing in 1886 that an Old Norse original version of Beowulf must have existed,[86] but that view was later debunked by Carl Wilhelm von Sydow (1914) who pointed out that Beowulf is fundamentally Christian and written at a time when any Norse tale would have most likely been pagan.[87]

Grettis saga

The epic's possible connection to Grettis saga, an Icelandic family saga, was made early on by Guðbrandur Vigfússon (1878).[88]

Grettis saga is a story about Grettir Ásmundarson, a great-grandson of an Icelandic settler, and so cannot be as old as Beowulf. Axel Olrik (1903) claimed that on the contrary, this saga was a reworking of Beowulf, and others followed suit.[86]

However, Friedrich Panzer (1910) wrote a thesis in which both Beowulf and Grettis saga drew from a common folkloric source, and this encouraged even a detractor such as W. W. Lawrence to reposition his view, and entertain the possibility that certain elements in the saga (such as the waterfall in place of the mere) retained an older form.[86]

The viability of this connection has enjoyed enduring support, and was characterized as one of the few Scandinavian analogues to receive a general consensus of potential connection by Theodore M. Andersson (1998).[89] But that same year, Magnús Fjalldal published a volume challenging the perception that there is a close parallel, and arguing that tangential similarities were being overemphasized as analogies.[90]

Hrolf kraki and Bodvar Bjarki

Another candidate for an analogue or possible source is the story of Hrolf kraki and his servant, the legendary bear-shapeshifter Bodvar Bjarki. The story survives in Old Norse Hrólfs saga kraka and Saxo's Gesta Danorum. Hrolf kraki, one of the Skjöldungs, even appears as "Hrothulf" in the Anglo-Saxon epic. Hence a story about him and his followers may have developed as early as the 6th century.[91]

International folktale sources

Bear's Son Tale

Friedrich Panzer (1910) wrote a thesis that the first part of Beowulf (the Grendel Story) incorporated preexisting folktale material, and that the folktale in question was of the Bear's Son Tale (Bärensohnmärchen) type, which has surviving examples all over the world.[92][86]

This tale type was later catalogued as international folktale type 301, now formally entitled "The Three Stolen Princesses" type in Hans Uther's catalogue, although the "Bear's Son" is still used in Beowulf criticism, if not so much in folkloristic circles.[86]

However, although this folkloristic approach was seen as a step in the right direction, "The Bear's Son" tale has later been regarded by many as not a close enough parallel to be a viable choice.[93] Later, Peter A. Jorgensen, looking for a more concise frame of reference, coined a "two-troll tradition" that covers both Beowulf and Grettis saga: "a Norse 'ecotype' in which a hero enters a cave and kills two giants, usually of different sexes";[94] which has emerged as a more attractive folk tale parallel, according to a 1998 assessment by Andersson.[95][96]

Celtic folktales

Similarity of the epic to the Irish folktale "The Hand and the Child" had already been noted by Albert S. Cook (1899), and others even earlier,[lower-alpha 5][97][87][lower-alpha 6] Swedish folklorist Carl Wilhelm von Sydow (1914) then made a strong argument for the case of parallelism in "The Hand and the Child", because the folktale type demonstrated a "monstrous arm" motif that corresponded with Beowulf wrenching off Grendel's arm. For no such correspondence could be perceived in the Bear's Son Tale or Grettis saga.[lower-alpha 7][98][97]

James Carney and Martin Puhvel also agree with this "Hand and the Child" contextualisation.[lower-alpha 8] Puhvel supported the "Hand and the Child" theory through such motifs as (in Andersson's words) "the more powerful giant mother, the mysterious light in the cave, the melting of the sword in blood, the phenomenon of battle rage, swimming prowess, combat with water monsters, underwater adventures, and the bear-hug style of wrestling."[99]

In the Mabinogion Teyrnon discovers the otherworldly boy child Pryderi fab Pwyll, the principle character of the cycle, after cutting off the arm of a monstrous beast which is stealing foals from his stables, an episode which is highly reminiscent in its description of the Grendel tale.

Classical sources

Attempts to find classical or Late Latin influence or analogue in Beowulf are almost exclusively linked with Homer's Odyssey or Virgil's Aeneid. In 1926, Albert S. Cook suggested a Homeric connection due to equivalent formulas, metonymies, and analogous voyages.[100] In 1930, James A. Work also supported the Homeric influence, stating that encounter between Beowulf and Unferth was parallel to the encounter between Odysseus and Euryalus in Books 7–8 of the Odyssey, even to the point of both characters giving the hero the same gift of a sword upon being proven wrong in their initial assessment of the hero's prowess. This theory of Homer's influence on Beowulf remained very prevalent in the 1920s, but started to die out in the following decade when a handful of critics stated that the two works were merely "comparative literature",[101] although Greek was known in late 7th century England: Bede states that Theodore of Tarsus, a Greek, was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 668, and he taught Greek. Several English scholars and churchmen are described by Bede as being fluent in Greek due to being taught by him; Bede claims to be fluent in Greek himself.[102]

Frederick Klaeber, among others, argued for a connection between Beowulf and Virgil near the start of the 20th century, claiming that the very act of writing a secular epic in a Germanic world represents Virgilian influence. Virgil was seen as the pinnacle of Latin literature, and Latin was the dominant literary language of England at the time, therefore making Virgilian influence highly likely.[103] Similarly, in 1971, Alistair Campbell stated that the apologue technique used in Beowulf is so rare in epic poetry aside from Virgil that the poet who composed Beowulf could not have written the poem in such a manner without first coming across Virgil's writings.[104]

Biblical influences

It cannot be denied that Biblical parallels occur in the text, whether seen as a pagan work with "Christian colouring" added by scribes or as a "Christian historical novel, with selected bits of paganism deliberately laid on as 'local colour'," as Margaret E. Goldsmith did in "The Christian Theme of Beowulf".[105] Beowulf channels the Book of Genesis, the Book of Exodus, and the Book of Daniel[106] in its inclusion of references to the Genesis creation narrative, the story of Cain and Abel, Noah and the flood, the Devil, Hell, and the Last Judgment.[105]

Dialect

| Part of a series on |

| Old English |

|---|

|

Dialects

|

|

History |

The poem mixes the West Saxon and Anglian dialects of Old English, though it predominantly uses West Saxon, as do other Old English poems copied at the time.[107]

There is a wide array of linguistic forms in the Beowulf manuscript. It is this fact that leads some scholars to believe that Beowulf has endured a long and complicated transmission through all the main dialect areas.[108] The poem retains a complicated mix of the following dialectical forms: Mercian, Northumbrian, Early West Saxon, Kentish and Late West Saxon.[45]:20–21 There are in Beowulf more than 3100 distinct words, and almost 1300 occur exclusively, or almost exclusively, in this poem and in the other poetical texts. Considerably more than one-third of the total vocabulary is alien from ordinary prose use. There are, in round numbers, three hundred and sixty uncompounded verbs in Beowulf, and forty of them are poetical words in the sense that they are unrecorded or rare in the existing prose writings. One hundred and fifty more occur with the prefix ge- (reckoning a few found only in the past-participle), but of these one hundred occur also as simple verbs, and the prefix is employed to render a shade of meaning which was perfectly known and thoroughly familiar except in the latest Anglo-Saxon period. The nouns number sixteen hundred. Seven hundred of them, including those formed with prefixes, of which fifty (or considerably more than half) have ge-, are simple nouns, at the highest reckoning not more than one-quarter is absent in prose. That this is due in some degree to accident is clear from the character of the words, and from the fact that several reappear and are common after the Norman Conquest.[109]

Form and metre

An Old English poem such as Beowulf is very different from modern poetry. Anglo-Saxon poets typically used alliterative verse, a form of verse in which the first half of the line (the a-verse) is linked to the second half (the b-verse) through similarity in initial sound. In addition, the two-halves are divided by a caesura: "Oft Scyld Scefing \\ sceaþena þreatum" (l. 4). This verse form maps stressed and unstressed syllables onto abstract entities known as metrical positions. There is no fixed number of beats per line: the first one cited has three (Oft SCYLD SCEFING, with ictus on the suffix -ING) whereas the second has two (SCEAþena ÞREATum).

The poet has a choice of epithets or formulae to use in order to fulfil the alliteration. When speaking or reading Old English poetry, it is important to remember for alliterative purposes that many of the letters are not pronounced in the same way as in modern English. The letter ⟨h⟩, for example, is always pronounced (Hroðgar: [ˈhroðgar]), and the digraph ⟨cg⟩ is pronounced [dʒ], as in the word edge. Both ⟨f⟩ and ⟨s⟩ vary in pronunciation depending on their phonetic environment. Between vowels or voiced consonants, they are voiced, sounding like modern ⟨v⟩ and ⟨z⟩, respectively. Otherwise they are unvoiced, like modern ⟨f⟩ in fat and ⟨s⟩ in sat. Some letters which are no longer found in modern English, such as thorn, ⟨þ⟩, and eth, ⟨ð⟩ – representing both pronunciations of modern English ⟨th⟩, as /θ/ in thing and /ð/ this – are used extensively both in the original manuscript and in modern English editions. The voicing of these characters echoes that of ⟨f⟩ and ⟨s⟩. Both are voiced (as in this) between other voiced sounds: oðer, laþleas, suþern. Otherwise they are unvoiced (as in thing): þunor, suð, soþfæst.

Kennings are also a significant technique in Beowulf. They are evocative poetic descriptions of everyday things, often created to fill the alliterative requirements of the metre. For example, a poet might call the sea the "swan-road" or the "whale-road"; a king might be called a "ring-giver." There are many kennings in Beowulf, and the device is typical of much of classic poetry in Old English, which is heavily formulaic. The poem also makes extensive use of elided metaphors.[110]

J. R. R. Tolkien argued in Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics that the poem is not an epic, and, while no conventional term exactly fits, the nearest would be elegy.[111]

Interpretation and criticism

The history of modern Beowulf criticism is often said to begin with J. R. R. Tolkien,[112] author and Merton professor of Anglo-Saxon at University of Oxford, who in his 1936 lecture to the British Academy criticised his contemporaries' excessive interest in its historical implications.[113] He noted in Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics that as a result the poem's literary value had been largely overlooked and argued that the poem "is in fact so interesting as poetry, in places poetry so powerful, that this quite overshadows the historical content..."[114]

Paganism and Christianity

In historical terms, the poem's characters would have been Norse pagans (the historical events of the poem took place before the Christianisation of Scandinavia), yet the poem was recorded by Christian Anglo-Saxons who had mostly converted from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism around the 7th century – both Anglo-Saxon paganism and Norse paganism share a common origin as both are forms of Germanic paganism. Beowulf thus depicts a Germanic warrior society, in which the relationship between the lord of the region and those who served under him was of paramount importance.[115]

In terms of the relationship between characters in Beowulf to God, one might recall the substantial amount of paganism that is present throughout the work. Literary critics such as Fred C. Robinson argue that the Beowulf poet tries to send a message to readers during the Anglo-Saxon time period regarding the state of Christianity in their own time. Robinson argues that the intensified religious aspects of the Anglo-Saxon period inherently shape the way in which the poet alludes to paganism as presented in Beowulf. The poet calls on Anglo-Saxon readers to recognize the imperfect aspects of their supposed Christian lifestyles. In other words, the poet is referencing their "Anglo-Saxon Heathenism." In terms of the characters of the epic itself, Robinson argues that readers are "impressed" by the courageous acts of Beowulf and the speeches of Hrothgar (181). But one is ultimately left to feel sorry for both men as they are fully detached from supposed "Christian truth" (181). The relationship between the characters of Beowulf, and the overall message of the poet, regarding their relationship with God is debated among readers and literary critics alike.

At the same time, Richard North argues that the Beowulf poet interpreted "Danish myths in Christian form" (as the poem would have served as a form of entertainment for a Christian audience), and states: "As yet we are no closer to finding out why the first audience of Beowulf liked to hear stories about people routinely classified as damned. This question is pressing, given... that Anglo-Saxons saw the Danes as 'heathens' rather than as foreigners."[116] Grendel's mother and Grendel are described as descendants of Cain, a fact which some scholars link to the Cain tradition.[117]

Other scholars disagree, however, as to the meaning and nature of the poem: is it a Christian work set in a Germanic pagan context? The question suggests that the conversion from the Germanic pagan beliefs to Christian ones was a prolonged and gradual process over several centuries, and it remains unclear the ultimate nature of the poem's message in respect to religious belief at the time it was written. Robert F. Yeager notes the facts that form the basis for these questions:

That the scribes of Cotton Vitellius A.XV were Christian beyond doubt, and it is equally sure that Beowulf was composed in a Christianised England since conversion took place in the sixth and seventh centuries. The only Biblical references in Beowulf are to the Old Testament, and Christ is never mentioned. The poem is set in pagan times, and none of the characters is demonstrably Christian. In fact, when we are told what anyone in the poem believes, we learn that they are pagans. Beowulf's own beliefs are not expressed explicitly. He offers eloquent prayers to a higher power, addressing himself to the "Father Almighty" or the "Wielder of All." Were those the prayers of a pagan who used phrases the Christians subsequently appropriated? Or, did the poem's author intend to see Beowulf as a Christian Ur-hero, symbolically refulgent with Christian virtues?[118]

The location of the composition of the poem is also intensely disputed. In 1914, F.W. Moorman, the first professor of English Language at University of Leeds, claimed that Beowulf was composed in Yorkshire,[119] but E. Talbot Donaldson claims that it was probably composed more than twelve hundred years ago, during the first half of the eighth century, and that the writer was a native of what was then called West Mercia, located in the Western Midlands of England. However, the late tenth-century manuscript "which alone preserves the poem" originated in the kingdom of the West Saxons – as it is more commonly known.[120] Donaldson wrote that "the poet who put the materials into their present form was a Christian and ... poem reflects a Christian tradition".[121]

Politics and warfare

Stanley B. Greenfield has suggested that references to the human body throughout Beowulf emphasise the relative position of thanes to their lord. He argues that the term "shoulder-companion" could refer to both a physical arm as well as a thane (Aeschere) who was very valuable to his lord (Hrothgar). With Aeschere's death, Hrothgar turns to Beowulf as his new "arm."[122] Also, Greenfield argues the foot is used for the opposite effect, only appearing four times in the poem. It is used in conjunction with Unferð (a man described by Beowulf as weak, traitorous, and cowardly). Greenfield notes that Unferð is described as "at the king's feet" (line 499). Unferð is also a member of the foot troops, who, throughout the story, do nothing and "generally serve as backdrops for more heroic action."[123]

Daniel Podgorski has argued that the work is best understood as an examination of inter-generational vengeance-based conflict, or feuding.[124] In this context, the poem operates as an indictment of feuding conflicts as a function of its conspicuous, circuitous, and lengthy depiction of the Geatish-Swedish wars—coming into contrast with the poem's depiction of the protagonist Beowulf as being disassociated from the ongoing feuds in every way.[124]

See also

- List of Beowulf characters

- On Translating Beowulf

- Sutton Hoo helmet § Beowulf

- Heliand, a Germanic epic and the largest known work of written Old Saxon

References

Notes

- "wíg" means "fight, battle, war, conflict"[17] and "láf" means "remnant, left-over"[18]

- That is, R.D. Fulk's 1992 A History of Old English Meter.

- For instance, by Chauncey Brewster Tinker in The Translations of Beowulf,[69] a comprehensive survey of 19th-century translations and editions of Beowulf.

- Ecclesiastical or biblical influences are only seen as adding "Christian color", in Andersson's survey. Old English sources hinges on the hypothesis that Genesis A predates Beowulf.

- Ludwig Laistner (1889), II, p. 25; Stopford Brooke, I, p. 120; Albert S. Cook (1899) pp. 154–156.

- In the interim, Max Deutschbein (1909) is credited by Andersson to be the first person to present the Irish argument in academic form. He suggested the Irish Feast of Bricriu (which is not a folktale) as a source for Beowulf—a theory that was soon denied by Oscar Olson.[87]

- von Sydow was also anticipated by Heinz Dehmer in the 1920s as well besides the writers from the 19th century in pointing out "The Hand and the Child" as a parallel.[98]

- Carney also sees the Táin Bó Fráech story (where a half-fairy hero fights a dragon in the "Black Pool (Dubh linn)"), but this has not received much support for forty years, as of Andersson's writing.

Citations

- Hanna, Ralph (2013). Introducing English Medieval Book History: Manuscripts, their Producers and their Readers. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9780859898713. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- "Beowulf". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins.

- Chase, Colin (1997). The dating of Beowulf. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 9–22.

- Robinson 2001, p. 143: "The name of the author who assembled from tradition the materials of his story and put them in their final form is not known to us."

- Robinson 2001: "Like most Old English stories, Beowulf has no title in the unique manuscript in which it survives (British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, which was copied round the year 1000 AD), but modern scholars agree in naming it after the hero whose life is its subject".

- Mitchell & Robinson 1998, p. 6.

- Chickering, Howell D. (1977). Beowulf (dual-language ed.). New York: Doubleday.

- Newton, Sam (1993). The Origins of Beowulf and the Pre-Viking Kingdom of East Anglia. Woodbridge, Suffolk, ENG: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-361-4.

- Waugh, Robin (1997). "Literacy, Royal Power, and King-Poet Relations in Old English and Old Norse Compositions". Comparative Literature. 49 (4): 289–315. doi:10.2307/1771534. JSTOR 1771534.

- Noted, for example, by John Grigsby, Beowulf & Grendel 2005:12.

- Shippey, TA (Summer 2001). "Wicked Queens and Cousin Strategies in Beowulf and Elsewhere, Notes and Bibliography". The Heroic Age (5).

- Carruthers, Leo M. (1998). Beowulf. Didier Erudition. p. 37. ISBN 9782864603474. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Niles, John D. (October 2006). "Beowulf's Great Hall". History Today. 56 (10): 40–44.

- Anderson, Carl Edlund (1999). "Formation and Resolution of Ideological Contrast in the Early History of Scandinavia" (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge, Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse & Celtic (Faculty of English). p. 115. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- Nerman, Birger (1925). Det svenska rikets uppkomst. Stockholm.

- Klingmark, Elisabeth. Gamla Uppsala, Svenska kulturminnen 59 (in Swedish). Riksantikvarieämbetet.

- "Wíg". Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- "Láf". Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Beowulf, 87–98

- Beowulf, 199–203

- Beowulf, 675–687

- Beowulf, 757–765

- Beowulf, 766–789

- Beowulf, 793–804

- Beowulf, 808–823

- Simpson, James (2012). The Norton Anthology of English Literature vol. A. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 58.

- Simpson, James (2012). The Norton Anthology of English Literature vol. A. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 70.

- Hansen, E. T. (2008). "Hrothgar's 'sermon' in Beowulf as parental wisdom". Anglo-Saxon England. 10: 53–67. doi:10.1017/S0263675100003203.

- Beowulf (PDF), SA: MU, archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2014.

- Lord, Albert (2000). The Singer of Tales, Volume 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 200. ISBN 9780674002838.

- Tolkien, J.R.R. (1997). Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics. Gale.

- Shippey, Tom (2007), "Tolkien and the Beowulf-poet", Roots and Branches, Walking Tree Publishers, ISBN 978-3-905703-05-4

- Neidorf, Leonard; Pascual, Rafael (2014). "The Language of Beowulf and the Conditioning of Kaluza's Law". Neophilologus. 98 (4). pp. 657–73. doi:10.1007/s11061-014-9400-x.

- Fulk, R.D. (2007). "Old English Meter and Oral Tradition: Three Issues Bearing on Poetic Chronology". Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 106. pp. 304–24. JSTOR 27712658.

- Davis, Nicola (8 April 2019). "Beowulf the work of single author, research suggests". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Neidorf, Leonard, ed. (2014), The Dating of Beowulf: A Reassessment, Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, ISBN 978-1-84384-387-0

- Lapidge, M. (2000). "The Archetype of Beowulf". Anglo-Saxon England. 29. pp. 5–41. doi:10.1017/s0263675100002398.

- Cronan, D (2004). "Poetic Words, Conservatism, and the Dating of Old English Poetry". Anglo-Saxon England. 33. pp. 23–50.

- Fulk, R.D. (1992), A History of Old English Meter

- Weiskott, Eric (2013). "Phantom Syllables in the English Alliterative Tradition". Modern Philology. 110 (4). pp. 441–58. doi:10.1086/669478.

- Hutcheson, B.R. (2004), "Kaluza's Law, The Dating of "Beowulf," and the Old English Poetic Tradition", The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 103 (3): 297–322, JSTOR 27712433

- DAVIS, CRAIG R. (2006). "An ethnic dating of "Beowulf"". Anglo-Saxon England. 35: 111–129. ISSN 0263-6751.

- "Cotton MS Vitellius A XV". British Library. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- Kiernan, Kevin S. (1998). "Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the "Beowulf"-Manuscript.Andy Orchard". Speculum. 73 (3): 879–881. doi:10.2307/2887546. JSTOR 2887546.

- Kiernan, Kevin (1981). Beowulf and the Beowulf Manuscript (1 ed.). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780472084128. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- Joy 2005, p. 2.

- Joy 2005, p. 24.

- Kiernan 1996, pp. 73–74.

- Kiernan, Kevin (16 January 2014). "Electronic Beowulf 3.0". U of Kentucky. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- Swanton, Michael (1997). Beowulf: Revised Edition. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0719051463. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Leonard Neidorf (2013). "Scribal errors of proper names in the Beowulf manuscript". Anglo-Saxon England. 42. pp. 249–69. doi:10.1017/s0263675113000124.

- Lapidge, Michael (1996). Anglo-Latin literature, 600–899. London: Hambledon Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-85285-011-1.

- Blackburn, FA (1897), "The Christian Coloring of Beowulf", PMLA, 12 (2): 210–17, doi:10.2307/456133, JSTOR 456133

- Benson, Larry D (1967), Creed, RP (ed.), "The Pagan Coloring of Beowulf", Old English Poetry: fifteen essays, Providence, Rhode Island: Brown University Press, pp. 193–213

- Lord 1960, p. 198.

- Zumthor 1984, pp. 67–92.

- Crowne, DK (1960), "The Hero on the Beach: An Example of Composition by Theme in Anglo-Saxon Poetry", Neuphilologische Mitteilungen, 61

- Benson, Larry D (1966), "The Literary Character of Anglo-Saxon Formulaic Poetry", Publications of the Modern Language Association, 81 (5): 334–41, doi:10.2307/460821, JSTOR 460821

- Benson, Larry (1970), "The Originality of Beowulf", The Interpretation of Narrative, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, pp. 1–44

- Foley, John M. Oral-Formulaic Theory and Research: An Introduction and Annotated Bibliography. New York: Garland, 1985. p. 126

- Watts, Ann C. (1969), The Lyre and the Harp: A Comparative Reconsideration of Oral Tradition in Homer and Old English Epic Poetry, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p. 124, ISBN 978-0-300-00797-8

- Gardner, Thomas. "How Free Was the Beowulf Poet?" Modern Philology. 1973. pp. 111–27.

- Foley, John Miles (1991), The Theory of Oral Composition: History and Methodology, Bloomington: IUP, pp. 109ff

- Bäuml, Franz H. "Varieties and Consequences of Medieval Literacy and Illiteracy", Speculum, Vol. 55, No. 2 (1980), pp. 243–44.

- Havelock, Eric Alfred (1963), A History of the Greek Mind, vol. 1. Preface to Plato, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Curschmann, Michael (1977), "The Concept of the Formula as an Impediment to Our Understanding of Medieval Oral Poetry", Medievalia et Humanistica, 8: 63–76

- Schaefer, Ursula (1992), "Vokalitat: Altenglische Dichtung zwischen Mundlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit", ScriptOralia (in German), Tübingen, 39

- Otter, Monika. "Vokalitaet: Altenglische Dichtung zwischen Muendlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit". Bryn Mawr Classical Review (9404). Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- Tinker, Chauncey Brewster (1903), The Translations of Beowulf, Gutenberg

- Orchard 2003a, pp. 4, 329–30.

- Osborn, Marijane (2003). "Annotated List of Beowulf Translations: Introduction". Arizona Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Schulman & Szarmach 2012, p. 4.

- Osborn, Marijane. "Annotated List of Beowulf Translations". Archived from the original on 21 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- Jaillant (2013)

- Beowulf (in Old English), Fordham

- Bloomfield, Josephine (June 1999). "Benevolent Authoritarianism in Klaeber's Beowulf: An Editorial Translation of Kingship" (PDF). Modern Language Quarterly. 60 (2): 129–159. doi:10.1215/00267929-60-2-129.

- Chickering 2002.

- Sims, Harley J. (2012). "Rev. of Fulk, Beowulf". The Heroic Age. 15.

- Kears, Carl (10 January 2018). "Eric Mottram and Old English: Revival and Re-Use in the 1970s" (PDF). The Review of English Studies. 69 (290): 430–454. doi:10.1093/res/hgx129 – via Oxford Academic.

- Geremia, Silvia (2007). "A Contemporary Voice Revisits the past: Seamus Heaney's Beowulf". Journal of Irish Studies (2): 57.

- Flood, Alison (17 March 2014). "JRR Tolkien translation of Beowulf to be published after 90-year wait". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- Acocella, Joan (2 June 2014). "Slaying Monsters: Tolkien's 'Beowulf'". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- Kay, Jennifer (16 July 2018). "Review: 'The Mere Wife' explores 'Beowulf' in the suburbs". Washington Post. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Andersson 1998, pp. 125, 129.

- Andersson 1998, pp. 130–131.

- Andersson 1998, p. 130.

- Andersson 1998, p. 135.

- Andersson 1998, pp. 130–31.

- Andersson 1998, p. 125.

- Magnús Fjalldal (1998). The long arm of coincidence: the frustrated connection between Beowulf and Grettis saga. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-4301-6.

- Chambers 1921, p. 55.

- Panzer 1910.

- Andersson 1998, pp. 137, 146.

- Andersson 1998, p. 134.

- Andersson 1998, p. 146.

- (Vickrey 2009, p. 209): "I shall continue to use the term Bear's Son for the folktale in question; it is established in Beowulf criticism and certainly Stitt has justified its retention".

- Puhvel 1979, p. 2–3.

- Andersson 1998, p. 136.

- Andersson 1998, p. 137.

- Cook 1926.

- Andersson 1998, p. 138.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, V.24

- Haber, Tom Burns (1931), A Comparative Study of the Beowulf and the Aeneid, Princeton

- Andersson 1998, pp. 140–41.

- Irving, Edward B., Jr. "Christian and Pagan Elements." A Beowulf Handbook. Eds. Bjork, Robert E. and John D. Niles. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1998. 175–92. Print.

- Andersson 1998, pp. 142–43.

- Slade, Benjamin (21 December 2003). "An Introduction to the Structure & Making of the Old English poem known as Beowulf or The Beowulf and the Beowulf-codex of the British Museum MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv". Beowulf on Steorarume. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- Tuso, Joseph F (1985). "Beowulf's Dialectal Vocabulary and the Kiernan Theory". South Central Review. 2 (2): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3189145. JSTOR 3189145.

- Girvan, Ritchie (1971), Beowulf and the Seventh Century Language and Content (print), New Feller Lane: London EC4: Methuen & CoCS1 maint: location (link)

- Greenblatt, Stephen; Abrams, Meyer Howard, eds. (2006). The Norton Anthology of English Literature (8th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 29. ISBN 9780393928303. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

The Norton Anthology of English Literature 8.

- Tolkien 1997, p. 31.

- Orchard 2003a, p. 7.

- Tolkien 2006, p. 7.

- Tolkien 1958, p. 7.

- Leyerle, John (1991). "The Interlace Structure of Beowulf". In Fulk, Robert Dennis (ed.). Interpretations of Beowulf: A Critical Anthology. Indiana UP. pp. 146–67. ISBN 978-0-253-20639-8. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- North 2006, p. 195.

- Williams, David (1982), Cain and Beowulf: A Study in Secular Allegory, University of Toronto Press

- Yeager, Robert F. "Why Read Beowulf?". National Endowment for the Humanities. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- F. W. Moorman, 'English Place Names and the Teutonic Sagas,'in Oliver Elton (ed.), English Association Essays and Studies, vol. 5 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1914) pp. 75ff

- Tuso, F Joseph (1975), Beowulf: The Donaldson Translation Backgrounds and Sources Criticism, New York: Norton & Co, p. 97

- Tuso, "Donaldson Translation," 98

- Greenfield 1989, p. 59.

- Greenfield 1989, p. 61.

- Podgorski, Daniel (3 November 2015). "Ending Unending Feuds: The Portent of Beowulf's Historicization of Violent Conflict". The Gemsbok. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

Sources

- Anderson, Sarah, ed. (2004), Introduction and historical/cultural contexts, Longman Cultural, ISBN 978-0-321-10720-6.

- Andersson, Theodore M. (1998), Bjork, Robert E.; Niles, John D. (eds.), "Sources and Analogues", A Beowulf Handbook, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 125–48, ISBN 9780803261501

- Carruthers, Leo (2011), "Rewriting Genres: Beowulf as Epic Romance", in Carruthers, Leo; Chai-Elsholz, Raeleen; Silec, Tatjana (eds.), Palimpsests and the Literary Imagination of Medieval England, New York: Palgrave, pp. 139–55, ISBN 9780230100268

- Chadwick, Nora K. (1959), "The Monsters and Beowulf", in Clemoes, Peter (ed.), The Anglo-Saxons: Studies in Some Aspects of Their History, London: Bowes & Bowes, pp. 171–203, OCLC 213750799

- Chambers, Raymond Wilson (1921), Beowulf: An Introduction to the Study of the Poem, The University Press}}

- Chance, Jane (1990), "The Structural Unity of Beowulf: The Problem of Grendel's Mother", in Damico, Helen; Olsen, Alexandra Hennessey (eds.), New Readings on Women in Old English Literature, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, pp. 248–61.

- Chickering, Howell D. (2002), "Beowulf and 'Heaneywulf': review" (PDF), The Kenyon Review, new, 24 (1): 160–78.

- Cook, Albert Stanburrough (1926), Beowulfian and Odyssean Voyages, New Haven: Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Creed, Robert P (1990), Reconstructing the Rhythm of Beowulf, University of Missouri, ISBN 9780826207227.

- Damico, Helen (1984), Beowulf's Wealhtheow and the Valkyrie Tradition, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 9780299095000.

- Greenfield, Stanley (1989), Hero and Exile, London: Hambleton Press.

- Heaney, Seamus (2000), Beowulf: A New Verse Translation, W.W. Norton & Company.

- Joy, Eileen A. (2005), "Thomas Smith, Humfrey Wanley, and the 'Little-Known Country' of the Cotton Library" (PDF), Electronic British Library Journal, retrieved 19 November 2014.

- "Anthropological and Cultural Approaches to Beowulf", The Heroic Age (5), Summer–Autumn 2001.

- Kiernan, Kevin (1996), Beowulf and the Beowulf Manuscript, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, ISBN 978-0-472-08412-8.

- Jaillant, Lise. "A Fine Old Tale of Adventure: Beowulf Told to the Children of the English Race, 1898–1908." Children's Literature Association Quarterly 38.4 (2013): 399–419

- Lerer, Seth (January 2012), "Dragging the Monster from the Closet: Beowulf and the English Literary Tradition", Ragazine.

- Lord, Albert (1960), The Singer of Tales, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, ISBN 9780674002838.

- Mitchell, Bruce; Robinson, Fred C (1998), Beowulf: an edition with relevant shorter texts, Oxford, UK; Malden, MA: Blackwell, ISBN 9780631172260.

- Neidorf, Leonard, ed. (2014), The Dating of Beowulf: A Reassessment, Cambridge: DS Brewer, ISBN 978-1-84384-387-0.

- Nicholson, Lewis E, ed. (1963), An Anthology of Beowulf Criticism, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, ISBN 978-0-268-00006-6.

- North, Richard (2006), "The King's Soul: Danish Mythology in Beowulf", Origins of Beowulf: From Vergil to Wiglaf, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Orchard, Andy (2003a), A Critical Companion to Beowulf, Cambridge: DS Brewer

- Orchard, Andy (2003b), Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript, Toronto: University of Toronto Press

- Panzer, Friedrich (1910), Studien zur germanischen Sagengeschichte - I. Beowulf, München: C. H. Beck (O. Beck), and II. Sigfrid (in German)

- Puhvel, Martin (2010). Beowulf and the Celtic Tradition. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. ISBN 9781554587698.

- Puhvel, Martin (1979), Beowulf and Celtic Tradition, Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, ISBN 9780889200630

- Robinson, Fred C (2001), The Cambridge Companion to Beowulf, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Robinson, Fred C (2002), "The Tomb of Beowulf", in the Norton Critical Edition of Beowulf: A Verse Translation, translated by Seamus Heaney and edited by Daniel Donoghue, New York, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, pp. 181–197

- Saltzman, Benjamin A (2018), "Secrecy and the Hermeneutic Potential in Beowulf", PMLA, 133: 36–55, doi:10.1632/pmla.2018.133.1.36.

- Schulman, Jana K; Szarmach, Paul E (2012), "Introduction", in Schulman, Jana K; Szarmach, Paul E (eds.), Beowulf and Kalamazoo, Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute, pp. 1–11, ISBN 978-1-58044-152-0.

- Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel (2006). Bliss, Alan (ed.). Finn and Hengest. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-261-10355-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel (2002). Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). Beowulf and the Critics. Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies.

- Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel (1997) [1958]. Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics and other essays. London: Harper Collins.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel (1958). Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics and other essays. London: Harper Collins.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trask, Richard M (1998), "Preface to the Poems: Beowulf and Judith: Epic Companions", Beowulf and Judith: Two Heroes, Lanham, MD: University Press of America, pp. 11–14

- Vickrey, John F. (2009), Beowulf and the Illusion of History, University of Delaware Press, ISBN 9780980149661

- Zumthor, Paul (1984), Englehardt, Marilyn C transl, "The Text and the Voice", New Literary History, 16: 67, doi:10.2307/468776, JSTOR 468776

External links

- Full digital facsimile of the manuscript on the British Library's Digitised Manuscripts website

- Electronic Beowulf, edited by Kevin Kiernan, 4th online edition (University of Kentucky/The British Library, 2015)

- Beowulf manuscript in The British Library's Online Gallery, with short summary and podcast

- Annotated List of Beowulf Translations: The List – Arizonal Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies

- online text (digitised from Elliott van Kirk Dobbie (ed.), Beowulf and Judith, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records, 4 (New York, 1953))

- Beowulf introduction Article introducing various translations and adaptations of Beowulf

- Beowulf translated by John Lesslie Hall at Standard Ebooks

- The tale of Beowulf (Sel.3.231); a digital edition of the proof-sheets with manuscript notes and corrections by William Morris in Cambridge Digital Library