Native Americans in the American Civil War

Native Americans in the American Civil War participated as individuals, bands, tribes, and nations in numerous skirmishes and battles.[1] 28,693 Native Americans served during the war,[2] mostly in the Confederate military and a minority in the Union.[3] They participated in battles such as Pea Ridge, Second Manassas, Antietam, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and in Federal assaults on Petersburg.[1] They were found in the Eastern, Western, and Trans-Mississippi Theaters. At the outbreak of the war, for example, most Cherokees sided with the Union, but they soon allied with the Confederacy.[4] Native Americans fought knowing they might jeopardize their sovereignty, unique cultures, and ancestral lands if they ended up on the losing side of the Civil War.[1][4]

Overview

Many Native American tribes fought for either side in the war including: the Delaware, Catawba, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Huron, Iroquois Confederacy, Kickapoo, Lumbee, Odawa, Ojibwe (Chippewa), Osage, Pamunkey, Pequot, Powhatan, Potawatomi, Seminole and Shawnee. Like other American communities, some tribes had members fighting on both sides of the war.[6]

During November 1861, the Creek, Black Creek Indians, and White Creek Indians of their tribe were led by Creek Chief Opothleyahola, fought three pitched battles (Battle of Round Mountain),[7] and the Battle of Chusto-Talasah[8] and the Battle of Chustenahlah [9] against Confederate troops and other Native Americans that joined the Confederates to reach Union lines in Kansas, and offer their services.[10]

Some Civil War battles occurred in Indian Territory.[11] The First Battle of Cabin Creek occurred July 1–2, 1863, along the Grand River in modern-day Mayes County, Oklahoma which involved the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry.[11] The Confederate force was led by General Stand Watie. A second battle was fought near the same location on September 19, 1864. This time the Union forces under Major Henry M. Hopkins were defeated by a Confederate force under Brigadier Generals Richard Gano and Stand Watie. This was the last major battle of the Civil War in Indian Territory.[12]

The Delaware demonstrated their "loyalty, daring and hardihood" during the attack of the Wichita Agency, or the Tonkawa Massacre in October 1862. A minor skirmish, Union Native Americans attacked Confederate Native Americans, and also killed five Confederate agents, took the Rebel flag and $1200 in Confederate currency, 100 ponies, and burned correspondence along with the Agency buildings.[1]

The Cherokee Nation had an internal civil war.[1] The Nation divided, with one side led by Principal Chief John Ross and the other by renegade Stand Watie.[1] Chief John Ross wanted to remain neutral throughout the war, but Confederate victories at First Manassas and Wilson's Creek forced the Cherokee to reassess their position.[1][6]

Stand Watie, along with many Cherokee, sided with the Confederate Army, in which he was made Colonel and commanded a battalion of Cherokee.[1] Reluctantly, on October 7, 1861, Chief Ross signed a treaty transferring all obligations due to the Cherokee from the U.S. Government to the Confederate States.[1] In the treaty, the Cherokee were guaranteed protection, rations of food, livestock, tools and other goods, as well as a delegate to the Confederate Congress at Richmond.[1] In exchange, the Cherokee would furnish ten companies of mounted men, and allow the construction of military posts and roads within the Cherokee Nation. However, no Indian regiment was to be called on to fight outside Indian Territory.[1] As a result of the Treaty, the 2nd Cherokee Mounted Rifles, led by Col. John Drew, was formed. Following the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, March 7–8, 1862, Drew's Mounted Rifles defected to the Union forces in Kansas, where they joined the Indian Home Guard. In the summer of 1862, Federal troops captured Chief Ross, who was paroled and spent the remainder of the war in Washington and Philadelphia proclaiming Cherokee loyalty to the Union army.[1]

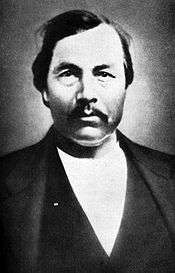

In his absence, Col. Stand Watie was chosen principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. He immediately drafted all Cherokee males aged 18–50 into Confederate military service.[1] Watie was a daring cavalry rider who was skilled at hit-and-run tactics. He was considered a genius in guerrilla warfare and the most successful field commander in the Trans-Mississippi West.[1] Promoted to brigadier general in May 1864, Watie was placed in charge of the Indian Cavalry Brigade, which was composed of the 1st and 2nd Cherokee Cavalry and battalions of Creek, Osage and Seminole. He achieved one of his more notable raids in the ambush of the steamboat J.R. Williams, which was bound for Fort Gibson. at Pleasant Bluff on the Arkansas River, near the present-day town of Tamaha, Oklahoma, on June 10, 1864, capturing the steamboat and its supplies, valued at $120,000. At the Second Battle of Cabin Creek (Indian Territory), Watie's cavalry brigade captured 129 supply wagons and 740 mules, took 120 prisoners, and left 200 casualties.[1]

The Cherokee who had not been removed were also caught in the middle of the Civil War. Some chose to side with the Confederate Army since they were located in the southern states.[1] The Thomas Legion, an Eastern Band of Confederate Cherokee, led by Col. William Holland Thomas, fought in the mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina.[1] Another 200 Cherokee formed the Junaluska Zouaves.[1] Nearly all Catawba adult males served the South in the 5th, 12th and 17th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry, Army of Northern Virginia. They distinguished themselves in the Peninsula Campaign, at Second Manassas, and Antietam, and in the trenches at Petersburg. A monument in Columbia, South Carolina, honors the Catawbas' service in the Civil War.[1] As a consequence of the regiments' high rate of dead and wounded, the continued existence of the Catawba people was jeopardized.[1]

In Virginia and North Carolina, the Pamunkey and Lumbee chose to serve the Union.[1] The Pamunkey served as civilian and naval pilots for Union warships and transports, while the Lumbee acted as guerrillas.[1] Members of the Iroquois Confederacy joined Company K, 5th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, while the Powhatan served as land guides, river pilots, and spies for the Army of the Potomac.[1]

During the Civil War, there was no distinction made when a Native American joined the U.S. Colored Troops. Well into the twentieth century, the word "colored" included not only African Americans, but Native Americans as well.[1] Individual accounts revealed that many Pequot from New England served in the 31st U.S. Colored Infantry of the Army of the Potomac, as well as other U.S.C.T. regiments.[1]

The most famous Native American unit in the Union army in the east was Company K of the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters.[1] The bulk of this unit was Ottawa, Delaware, Huron, Oneida, Potawami and Ojibwe.[1] They were assigned to the Army of the Potomac just as Gen. Ulysses S. Grant assumed command. Company K participated in the Battle of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, and captured 600 Confederate troops at Shand House east of Petersburg.[1] In their final military engagement at the Battle of the Crater, Petersburg, Virginia, on July 30, 1864, the Sharpshooters found themselves surrounded with little ammunition.[1] A lieutenant of the 13th United States Colored Infantry quoted their actions as:

[S]plendid work. Some of them were mortally wounded, and drawing their blouses over their faces, they chanted a death song and died – four of them in a group.[1]

General Ely S. Parker, a member of the Seneca tribe, created the articles of surrender which General Robert E. Lee signed at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Gen. Parker, who served as Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's military secretary and was a trained attorney, was once rejected for Union military service because of his race. At Appomattox, Lee is said to have remarked to Parker, "I am glad to see one real American here", to which Parker replied, "We are all Americans."[1]

The Cherokee Nation was the most negatively affected of all Native American tribes during the Civil War, its population declining from 21,000 to 15,000 by 1865. Despite the Federal government's promise to pardon all Cherokee involved with the Confederacy, the entire Nation was considered disloyal, and their rights were revoked. At the end of the war, Gen. Stand Watie was the last Confederate general to surrender, laying down arms two months after Gen. Robert E. Lee, and a month after Gen. E. Kirby Smith, commander of all troops west of the Mississippi.[1]

Problems in the Midwest and West

The west was mostly peaceful during the war due to the lack of U.S. occupation troops. The federal government was still taking control of native land, and there were continuous fights.[4] From January to May 1863, there were almost continuous fights in the New Mexico territory, as part of a concerted effort by the Federal government to contain and control the Apache; in the midst of all this, President Abraham Lincoln met with representatives from several major tribes, and informed them he felt concerned they would never attain the prosperity of the white race unless they turned to farming as a way of life.[1] The fighting led to the Sand Creek Massacre caused by Colonel J. M. Chivington, of the Colorado Territorial Militia, whom settlers asked to retaliate against natives.[4] With 900 volunteer militiamen, Chivington attacked a peaceful village of some 500 or more Arapaho and Cheyenne natives, killing women and children as well as warriors.[4] There were few survivors of the massacre.[4]

In July 1862, settlers fought against Santee Sioux in Minnesota.[4][13] Because the war absorbed so many government resources, the annuities owed to the Santee Sioux in Minnesota were not paid on time in the summer of 1862.[13] In addition, Long Trader Sibley refused the Santee Sioux access to food until the funds were delivered. In frustration, the Santee Sioux, led by Little Crow (Ta-oya-te-duta), attacked settlers in order to get supplies.[13] The Sioux killed 450–800 civilians.[14] After the Sioux lost, they were tried (without defense lawyers) and many were sentenced to death.[13]

When President Lincoln found out about the incident, he immediately requested full information about the convictions. He assigned two attorneys to examine the cases and differentiate between those guilty of murder and those who simply engaged in battle.[13] General Pope, as well as Long Trader Sibley, whose refusal to allow the Sioux access to food had been largely responsible for the war, were angered by Lincoln's failure to immediately authorize the executions.[13] They threatened that the local settlers would take action against the Sioux unless the President allowed the executions, and they quickly tried to push forward with them.[13] In addition, they arrested the rest of the Santee Sioux, 1,700 people, of whom most were women and children, although they were accused of no crime.

On December 6, 1861, based on information he was given, Lincoln authorized the execution of 39 Sioux, and ordered that the others be held pending further orders, "taking care that they neither escape nor are subjected to any unlawful violence."[13] On December 26, 39 men were taken. At the last minute, one was given a reprieve. It was not until years later that information became public that two men were executed who had not been authorized for punishment by President Lincoln.[13] In fact, one of these two men had saved a white woman's life during the fighting.[13] Little Crow was then murdered in July 1863, the year in which the Santees were transported to a reservation in Dakota Territory.[13]

Native Americans in the Confederate Army

Native Americans served in both the Union and Confederate military during the American Civil War.[1][2] Many of the tribes viewed the Confederacy as the better choice due to its opposition to a central federal system which lacked a respect for the sovereignty of Indian nations. In addition, some Native American tribes, such as the Creek and the Choctaw, were slaveholders and found a political and economic commonality with the Confederacy.[15]

Sir: To enable the Secretary of War most advantageously to perform the duties devolved upon him in relation to the Indian tribes by the second section of the Act to establish the War Department of February 21, 1861, it is deemed desirable that there should be established a Bureau of Indian Affairs, and, if the Congress concur in this view, I have the honor respectfully to recommend that provision be made for the appointment of a Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and for one clerk to aid him in the discharge of his official duties.

— Jefferson Davis to Howell Cobb, Confederate States of America – Message to Congress, March 1861[16]

At the beginning of the war, Albert Pike was appointed as Confederate envoy to Native Americans. In this capacity he negotiated several treaties, one such treaty was the Treaty with Choctaws and Chickasaws conducted in July 1861. The treaty covered sixty-four terms covering many subjects like Choctaw and Chickasaw nation sovereignty, Confederate States of America citizenship possibilities, and an entitled delegate in the House of Representatives of the Confederate States of America. The Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Catawba, and Creek tribes were the only tribes to fight on the Confederate side.

Cherokee

Cherokee in the Trans Mississippi Theater

Stand Watie, along with many Cherokee, sided with the Confederate Army, in which he was made colonel and commanded a battalion of Cherokee.[1] Reluctantly, on October 7, 1861, Chief Ross signed a treaty transferring all obligations due to the Cherokee from the U.S. Government to the Confederate States.[1] In the treaty, the Cherokee were guaranteed protection, rations of food, livestock, tools and other goods, as well as a delegate to the Confederate Congress at Richmond.[1] In exchange, the Cherokee would furnish ten companies of mounted men, and allow the construction of military posts and roads within the Cherokee Nation. However, no Indian regiment was to be called on to fight outside Indian Territory.[1] As a result of the treaty, the 2nd Cherokee Mounted Rifles, led by Col. John Drew, was formed. Following the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, March 7–8, 1862, Drew's Mounted Rifles defected to the Union forces in Kansas, where they joined the Indian Home Guard. In the summer of 1862, Federal troops captured Chief Ross, who was paroled and spent the remainder of the war in Washington and Philadelphia proclaiming Cherokee loyalty to the Union army.[1]

North Carolina Cherokee in the Western Theater

William Holland Thomas, the only white chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, recruited hundreds of Cherokees for the Confederacy, particularly for Thomas' Legion. The Legion, raised in September 1862, fought until the end of the war.

Choctaw

Choctaw Confederate battalions were formed in Indian Territory and later in Mississippi in support of the southern cause.

Choctaw in the Trans Mississippi Theater

The Choctaws, who were expecting support from the Confederates, got little. Webb Garrison, a Civil War historian, describes their response: when Confederate Brigadier General Albert Pike authorized the raising of regiments during the fall of 1860, Creeks, Choctaws, and Cherokees responded with considerable enthusiasm. Their zeal for the Confederate cause, however, began to evaporate when they found that neither arms nor pay had been arranged for them. A disgusted officer later acknowledged that "with the exception of a partial supply for the Choctaw regiment, no tents, clothing, or camp and garrison equippage was furnished to any of them."[17]

Albert Pike negotiated several treaties with Native American tribes, including the Treaty with Choctaws and Chickasaws in July 1861. The treaty covered sixty-four terms, covering many subjects like Choctaw and Chickasaw nation sovereignty, Confederate States of America citizenship possibilities, and an entitled delegate in the House of Representatives of the Confederate States of America.[18]

Up to this time, our protection was in the United States troops stationed at Fort Washita, under the command of Colonel Emory. But he, as soon as the Confederate troops had entered our country, at once abandoned us and the Fort; and, to make his flight more expeditious and his escape more sure, employed Black Beaver, a Shawnee Indian, under a promise to him of five thousand dollars, to pilot him and his troops out of the Indian country safely without a collision with the Texas Confederates; which Black Beaver accomplished. By this act the United States abandoned the Choctaws and Chickasaws.

[...]

Then, there being no other alternative by which to save their country and property, they, as the less of the two evils that confronted them, went with the Southern Confederacy.

— Julius Folsom, September 5, 1891, letter to H. B. Cushman

In Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory, Jackson McCurtain, who would later become a district chief, was elected as representative from Sugar Loaf County to the National Council in October 1859. On June 22, 1861, he enlisted in the First Regiment of Choctaw and Chickasaw Mounted Rifles. He was commissioned captain of Company G under the command of Colonel Douglas H. Cooper of the Confederate Army. In 1862 he became a lieutenant colonel of the First Choctaw Battalion.[19] The Choctaw probably owned over 2,000 slaves.[20]

Mississippi Choctaw in the Western Theater

In 1862, John W. Pierce created and financed his 1st Choctaw Battalion.[21] The battalion was headquartered at Newton Station, Mississippi in the early part of 1863. They were sent to rescue and assist surviving train crash victims on the Chunky Creek/River on February 19, 1863. After their rescue efforts, the Indian battalion tracked deserters in central Mississippi. When a massive federal expedition (out of New Orleans) was sent to Ponchatoula, Louisiana, the 1st Choctaw Battalion was sent as reinforcement for the Battle of Ponchatoula. The 1st Choctaw Battalion, identified as "Indian troops," was given credit for pushing back the "yankees" in southern newspapers. Not long after the battle, over half of the Choctaw soldiers deserted the battalion. After their desertion, Brigadier General John Adams recommended that the battalion be disbanded. On May 9, 1863, the 1st Choctaw Battalion was disbanded.

However, a number of 1st Choctaw Battalion members remained. Another federal expedition (once again out of New Orleans) surprised the 1st Choctaw Battalion remnant. Some were captured just north of Ponchatoula. Fourteen Indian prisoners were sent to New York.[22] They were incarcerated at Castle Williams during the entire summer of 1863. On occasion, the prisoners were showcased as entertainment for New Yorkers. Two died at a hospital on Governor's Island.[23] At the end of summer, the remaining members were sent back to New Orleans where they were never heard from again.

When members of the disbanded 1st Choctaw Battalion heard about the prisoners being sent to New York, they held a war council and drew a petition to be transferred to Samuel G. Spann's independent scouts. A delegation was sent to Richmond, Virginia, and the petition was granted. Spann's Battalion was headquartered in Mobile and, later, Tuscaloosa.[21] The Indians remained with Spann until the end of the War.

Native Americans in the Union Army

The Delaware tribe had a long history of allegiance to the U.S. government, despite removal to the Wichita Indian Agency in Oklahoma and the Indian Territory in Kansas.[1] On October 1, 1861 the Delaware people proclaimed their alliance to the Union.[1] A journalist from Harper's Weekly described them as being armed with tomahawks, scalping knives, and rifles.[1]

In January 1862, William Dole, U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, asked Native American agents to "engage forthwith all the vigorous and able-bodied Native Americans in their respective agencies."[1] The request resulted in the assembly of the 1st and 2nd Indian Home Guard.[1]

In Oklahoma, much of the Creek peoples sided with the Union.[7] The majority of the Creek initially sided with the Union as two-thirds of the people preferred to be guided by the advice of their chief Opothleyahola. However, former Chief McIntosh sided with the South, whose leaders appointed him a colonel in the Confederate Army.[6]

New York

Early in the war, acceptance of Native Americans in the Union Army was uneven. In New York State, prominent Natives such as Peter Wilson, Eli Parker and his brother, Newton were rebuffed when they sought to volunteer, but in October 1861, 25 Saint Regis Mohawk enrolled in the 98th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Ultimately at least 162 and as many as 300 New York natives served the Union. Newton Parker enlisted in June 1862 as a non-commissioned officer in the 53rd New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, and later transferred to Company D of the 132nd New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, known as the Tuscarora Company, and grant was commissioned as assistant adjutant general of volunteers on the staff of John E. Smith, a division general under Ulysses S. Grant, with the rank of captain on May 25, 1863, although never put in command of infantry.[24]

Aftermath

Native American communities were totally devastated by the War. The Trans Mississippi Theater saw the Native Nations reduced to rubble. Historians claim they were hardest hit of all who participated in the War. Of the 3,530 Native Americans who fought for the Union, 1,108 were killed, an incredibly high rate.

In the Western Theater, the Mississippi Choctaw were ignored and forgotten for nearly twenty years. It wasn't until 1900 when Samuel G. Spann began writing about his wartime experiences that the Mississippi Choctaw got some acknowledgment. Spann later commanded a U.C.V. camp in Mississippi. The Florida Seminole's recognition during the War was barely recorded. The North Carolina Cherokee was well remembered for their role. They created a U.C.V. Camp. South Carolina's Catawba erected a memorial in honor of their deeds.

Most tribes among Indigenous nations were negatively affected by the Civil War. In particular, the Creeks and the Cherokees suffered devastating losses. The Cherokee nation was the most implicated Indigenous nation in the Civil War, whether on the Union side or the Confederacy. During the Creeks’ and Cherokees’ first two months in the war, almost 300 died in Kansas while around 4,000 were killed overall by the end of December 1861. By the end of the first summer of the war, more than one tenth of the Creeks deceased, which was a similar death rate compared to most other tribes. As a result of the war, the conditions of many refugees still seeking help remained disastrous for many months after the end of the war. Many of those refugees suffered from starvation.

Overall, the Cherokee nation suffered more losses than any other Indigenous tribe. As a result of the war, many Cherokees were forced to flee the nation and head towards foreign lands for safety and survival. Around 22% of the Cherokee nation perished during the war. Many children were severely affected psychologically as they watched their family members get brutally killed or die of deplorable conditions. Among the Cherokees, about 35% of adult females were left as widows and a large percentage of children became orphans. Besides the enormous death toll, a huge amount of land was lost and the plentiful crops and livestock once grown were completely gone. Many who survived were considered “homeless refugees.” Nearly all structures in the nation were destroyed and the only option left was to rebuild.[25][26]

Tribes involved in battles

See also

- Native Americans and World War II

- Slavery among Native Americans in the United States

- Indian Territory in the American Civil War

- African Americans in the American Civil War

- German Americans in the American Civil War

- Hispanics in the American Civil War

- Irish Americans in the American Civil War

- Italian Americans in the Civil War

- Foreign enlistment in the American Civil War

References

- W. David Baird; et al. (January 5, 2009). ""We are all Americans", Native Americans in the Civil War". Native Americans.com. Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- Rodmans, Leslie. The Five Civilized Tribes and the American Civil War (PDF). p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011.

- "PATRIOT NATIONS | Conflicting Loyalties". americanindian.si.edu. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- "Native Americans in the Civil War". Ethic Composition of Civil War Forces (C.S & U.S.A.). January 5, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- Ely Parker Famous Native Americans

- Wiley Britton (January 5, 2009). "Union and Confederate Indians in the Civil War "Battles and Leaders of the Civil War"". Civil War Potpourri. Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- Chad Williams, "Battle of Round Mountain" Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

- Michael A. Hughes, "Battle of Chusto-Talasah." Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

- Michael A. Hughes, "Battle of Chustenahlah," "'Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

- William Loren Katz (2008). "Africans and Indians: Only in America". William Loren Katz. Archived from the original on May 29, 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- Angela Y. Walton-Raji (2008). "Battles Fought in Indian Territory and Battles Fought by I.T. Freedmen outside of Indian Territory". Oklahoma's Black Indians. Retrieved October 24, 2008.

- Steven L. Warren, "Battles of Cabin Creek," Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History

- "Native Americans". History Central.com. January 5, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- Kenneth Carley. The Dakota War of 1862.

- Rodman, Leslie. The Five Civilized Tribes and the American Civil War (PDF). p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011.

- "Confederate States of America – Message to Congress March 12, 1861 (Indian Affairs)". Yale Law School. 1861. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- Garrison, Webb (1995). "Padday Some Day". More Civil War Curiosities. Rutledge Hill Press.

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. "Choctaw". Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- "Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma: 1880 – Jackson F. McCurtain". 1880. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- "The Choctaw". Museum of the Red River. 2005. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009.

- Ferguson, Robert. "Southeastern Indians During The Civil War". The Backwoodsman. Vol. 39 no. 2 (Mar/Apr 2018 ed.). Bandera, Texas: Charlie Richie Sr. pp. 63–65. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- Spann, S. G. (December 1905). "Choctaw Indians As Confederate Soldiers". Confederate Veteran Magazine. Vol. XIII no. 12. pp. 560–561. Archived from the original on October 25, 2007. Retrieved February 6, 2008.

- Kidwell, Clara (1995). "The Choctaws in Mississippi after 1830". Choctaws and Missionaries in Mississippi, 1818–1918. University of Oklahoma. p. 170. ISBN 0-8061-2691-4.

- Armstrong, William H. Warrior in Two Camps: Ely S. Parker, Union General and Seneca Chief. Syracuse University Press, 1990. p80-83

- Crowe, Clint. "War in the Nations: The Devastation of a Removed People during the American Civil War." Order No. 3361692 University of Arkansas, 2009. Ann Arbor: ProQuest. Web. 15 Apr. 2019.

- Fritz, Emma Elizabeth. “they are carried in our Blood”: Violence and memory in the Nineteenth-Century Cherokee Nation.” Order No. 10274127 Oklahoma State University, 2017. Ann Arbor: ProQuest. Web. 18 Apr. 2019.

Further reading

- Confer, Clarissa W. The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War (Univ.of Oklahoma Press, 2007)

- Connole, Joseph. The Civil War and the Subversion of American Indian Sovereignty (McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2017)

- Dale, Edward Everett. "The Cherokees in the Confederacy." Journal of Southern History 13.2 (1947): 159-185. in JSTOR

- Fisher, Paul Thomas. "Confederate empire and the Indian treaties: Pike, McCulloch, and the Five Civilized Tribes, 1861-1862" (MA thesis Baylor U. 2011). online; bibliography pp 107–19.

- Gibson, Arrell Morgan. "Native Americans and the Civil War," American Indian Quarterly (1985) 9#4 pp. 385–410 in JSTOR

- Gibson, Arrell (1981), Oklahoma, a History of Five Centuries, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-1758-3

- Hauptman, Laurence M. Between Two Fires: American Indians in the Civil War (1995) excerpt

- Johnston, Carolyn. Cherokee Women in Crisis: Trail of Tears, Civil War, and Allotment, 1838-1907 (University of Alabama Press, 2003).

- Minges, Patrick. Slavery in the Cherokee Nation: The Keetowah Society and the Defining of a People, 1855-1867 (Routledge, 2003)

- Moore, Jessie Randolph. "The Five Great Indian Nations: Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Creek: The Part They Played in Behalf of the Confederacy in the War Between the States." Chronicles of Oklahoma 29 (1951): 324-336.

- Smith, Troy. "The Civil War Comes to Indian Territory," Civil War History (Sept 2013) 59#3 pp 279–319 online

- Stevens, Scott Manning. "American Indians and the Civil War" in Why You Can't Teach United States' History without American Indians (Univ. of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Press, 2015).

- Wickett, Murray R. Contested Territory: Whites, Native Americans and African Americans in Oklahoma, 1865-1907 (Louisiana State Univ. Press, 2000)

Primary sources

- Edwards, Whit. "The Prairie Was on Fire": Eyewitness Accounts of the Civil War in the Indian Territory (Oklahoma Historical Society, 2001)