Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War

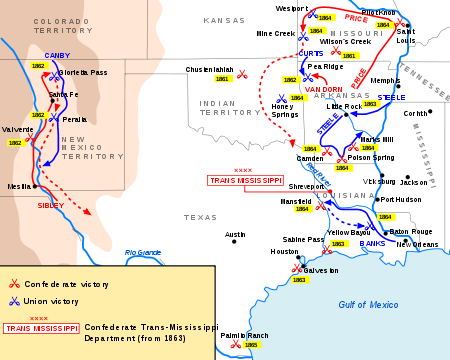

The Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War consists of the major military operations west of the Mississippi River. The area is often thought of as excluding the states and territories bordering the Pacific Ocean, which formed the Pacific Coast Theater of the American Civil War (1861-1865).

The campaign classification established by the National Park Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior[1] is more fine-grained than the one used in this article. Some minor NPS campaigns have been omitted and some have been combined into larger categories. Only a few of the 75 major battles the NPS classifies for this theater are described. Boxed text in the right margin show the NPS campaigns associated with each section.

Activity in this theater in 1861 was dominated largely by the dispute over the status of the border state of Missouri. The Missouri State Guard, allied with the Confederacy, won important victories at the Battle of Wilson's Creek and the First Battle of Lexington. However, they were driven back at the First Battle of Springfield. A Union army under Samuel Ryan Curtis defeated the Confederate forces at the Battle of Pea Ridge in northwest Arkansas in March 1862, solidifying Union control over most of Missouri. The areas of Missouri, Kansas, and the Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma) were marked by extensive guerrilla activity throughout the rest of the war, the most well-known incident being the infamous Lawrence massacre in the Unionist town of Lawrence, Kansas of August 1863.

In the spring of 1862, Confederate forces pushed north along the Rio Grande River from El Paso, Texas through the New Mexico Territory, but were stopped at the Battle of Glorieta Pass (March 26–28, 1862). In 1863, General Edmund Kirby Smith took command of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department, and unsuccessfully tried to relieve the Siege of Vicksburg by Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant on the opposite eastern banks of the Mississippi River in the state of Mississippi. As a result of the long campaign / siege and surrender in July 1863 by Gen. John C. Pemberton, the Union gained control of the entire Mississippi River, splitting the Confederacy. This left the Trans-Mississippi Department almost completely isolated from the rest of the Confederate States to the east. It became nicknamed and known as "Kirby Smithdom", emphasizing the Confederate Government's lack of direct control over the region.

In the 1864 Red River Campaign, a U.S. force under Major General Nathaniel P. Banks tried to gain control over northwestern Louisiana, but was thwarted by Confederate troops commanded by Richard Taylor. Price's Raid, an attempt led by Major General Sterling Price to recapture Missouri for the Confederacy, ended when Price's troops were defeated in the Battle of Westport that October. On June 2, 1865, after all other major Confederate armies in the field to the east had surrendered, Kirby Smith officially surrendered his command in Galveston, Texas. On June 23, Stand Watie, who commanded Southern troops in the Indian Territory, became the last Confederate general to surrender.

Principal Union Commanders of the Trans-Mississippi Theater

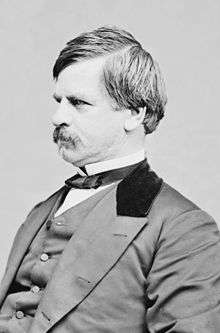

Maj. Gen.

Nathaniel P. Banks,

USA

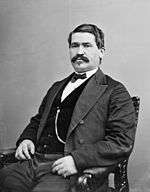

Maj. Gen.

James G. Blunt,

USA

Maj. Gen.

Edward Canby,

USA

Maj. Gen.

Samuel R. Curtis,

USA

Maj. Gen.

John C. Frémont,

USA

Maj. Gen.

Nathaniel Lyon,

USA

Maj. Gen.

John Pope,

USA

Maj. Gen.

William S. Rosecrans,

USA

Maj. Gen.

John Schofield,

USA

Principal Confederate Commanders of the Trans-Mississippi Theater

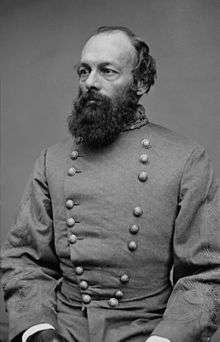

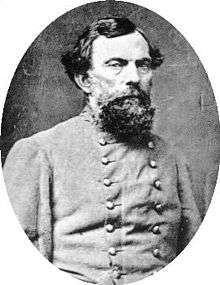

Gen.

Edmund Kirby Smith,

CSA

Lt. Gen.

Theophilus H. Holmes,

CSA

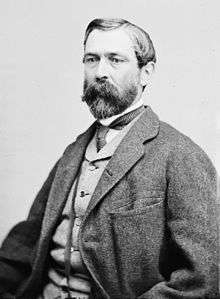

Lt. Gen.

Richard Taylor,

CSA

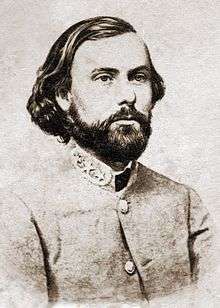

Maj. Gen.

Thomas C. Hindman,

CSA

Maj. Gen.

John B. Magruder,

CSA

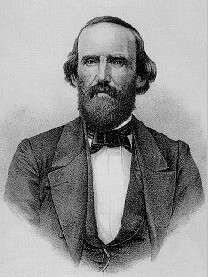

Maj. Gen.

Sterling Price,

MSG, CSA

Maj. Gen.

Earl Van Dorn,

CSA

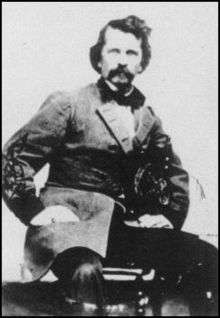

Brig. Gen.

Henry Hopkins Sibley,

CSA

Brig. Gen.

Benjamin McCulloch,

CSA

Brig. Gen.

Stand Watie,

CSA

Trans-Mississippi Department

The Confederate States Army's Trans-Mississippi Department was formed May 26, 1862, to include Missouri, Arkansas, Texas, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), and Louisiana west of the Mississippi River. It absorbed the previous Trans-Mississippi District (Department Number Two), which had been organized January 10, 1862, to include that part of Louisiana north of the Red River, the Indian Territory (later State of Oklahoma, 1907), and the states of Missouri and Arkansas, except for the country east of St. Francis County, Arkansas, to Scott County, Missouri. The combined department had its headquarters at Shreveport, Louisiana, and Marshall, Texas.

Commanders

- Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn, CSA, (January 10, 1862 – May 23, 1862, District part of Department Number Two)

- Brig. Gen. Paul O. Hébert, CSA, (May 26, 1862 – June 20, 1862)

- Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder, CSA, (assigned June 20, 1862, but did not accept)

- Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman, CSA, (June 20, 1862 – July 16, 1862)

- Lt. Gen. Theophilus H. Holmes, CSA, (July 30, 1862 – February 9, 1863)

- Lt. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, CSA, (March 7, 1863 – April 19, 1865)

- Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, CSA, (April 19, 1865 – April 22, 1865)

- General Edmund Kirby Smith, CSA, (April 22, 1865 – May 26, 1865)

Confederate Territory of Arizona and Federal New Mexico Territory

In 1861, the Confederate States Army launched a successful campaign into the United States' recently organized Territory of New Mexico (1851), of the present day states of Arizona and New Mexico. Residents in the southern portions of this Territory adopted a secession ordinance of their own and requested that Confederate States of America military forces stationed further east in nearby Texas assist them in removing Union Army forces still stationed there. The Confederate Territory of Arizona was proclaimed by Col. John Baylor after victories in the First Battle of Mesilla on July 25, 1861, at Mesilla, New Mexico, and the capture of several Union forces. Southern forces advanced northward through the Rio Grande Valley, capturing Albuquerque and Santa Fe in March 1862. Attempts to press further northward in the territory were unsuccessful, and Confederate forces withdrew from Arizona completely in 1862 when Union reinforcements arrived from California.

The Battle of Glorieta Pass on March 26–28, 1862, was a relatively small skirmish in terms of both numbers involved and losses (140 Union, 190 Confederate). Yet the military/political strategic issues were large, and the battle was decisive in resolving them. The Confederates might well have taken Fort Union further north in the Rio Grande river valley and even Denver, the territorial capital of the northern Colorado Territory had they not been stopped at Glorieta. As one Texan put it, "If it had not been for those devils from Pike's Peak, this country would have been ours."

This small battle dissolved any possibility of the Confederacy taking New Mexico and the far west territories. In April, the California Column, Union volunteers from California, pushed the remaining Confederates out of present-day Arizona at the Battle of Picacho Pass. In the Eastern United States, the fighting dragged on for three more years, but in the Southwest the war against the Confederacy was over, but the war against the Apache, Navaho and Comanche continued for the California garrisons until they were replaced by U. S. Army troops after the Civil War ended.

Several battles occurred between Confederate soldiers and or militia within Confederate Arizona, the height of the Apache campaigns against rebel forces was during mid to late 1861.

Missouri, Arkansas, and Kansas

Though a slave state with a highly organized and militant secessionist movement, thanks to the pro-slavery "border ruffians" who battled antislavery militias in Kansas in the 1850s, Missourians sided with the Union by a ratio of two or three to one. Pro-Confederate Governor Claiborne F. Jackson and his small state guard under General Sterling Price linked up with Confederate forces under General Ben McCulloch. After victories at the Battle of Wilson's Creek and at Lexington, Missouri, Confederate forces were driven out of the state by the arrival of large Union forces in February 1862 and were effectively locked out by defeat at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, on March 6–8.

A guerrilla conflict began to wrack Missouri. Gangs of Confederate insurgents, commonly known as "bushwhackers", ambushed and battled Union troops and Unionist state militia forces. Much of the fighting was between Missourians of different persuasions; both sides carried out large-scale atrocities against civilians, ranging from forced resettlement to murder. Historians estimate that the population of the state fell by one-third during the war; most survived but fled or were driven out by one side or the other. Many of the most brutal bushwhacker leaders, such as William C. Quantrill and William T. "Bloody Bill" Anderson, won national notoriety. A group of their followers remained under arms and carried out robberies and murders (which they may have considered to be ongoing guerilla resistance) for sixteen years after the war, under the leadership of Jesse James, his brother Frank James, and Cole Younger and his brothers.

By most measures, the Confederate guerrilla insurgency in Missouri during the Civil War was the worst such conflict ever to occur on American soil. By one calculation, nearly twenty-seven thousand Missourians died in the violence. Historians have offered various explanations for the anomalously high level of guerrilla activity in Missouri, including the possibility that the violence was linked to thousands of court-ordered sales of property belonging to the state's Confederate sympathizers, beginning in 1862 and continuing throughout the war. The property sales arose from court judgments for defaulted debts incurred early in the war to arm rebel troops.[2]

Kansas was admitted to the Union as a free state on January 29, 1861, three months before the opening battle of the war at Fort Sumter. In August, 1863, Quantrill led his raiders into Kansas destroying much of the city of Lawrence and murdering over 150 unarmed men and boys in what became known as the Lawrence Massacre. On October 25, 1864, during Confederate Major General Sterling Price's raid into Kansas and Missouri, in three interconnected actions, Price's forces were defeated at the Battles of Marais des Cygnes, Mine Creek (one of the largest cavalry engagements of the war), and a final battle at Marmiton River, sealing the fate of Price's campaign and forcing his withdrawal into Indian Territory, and eventually Texas, before returning to Arkansas.

Texas and Louisiana

The Union mounted several attempts to capture the trans-Mississippi regions of Texas and Louisiana from 1862 until the war's end. With ports to the east under blockade or captured, Texas in particular became a blockade-running haven. Referred to as the "back door" of the Confederacy, Texas and western Louisiana continued to provide cotton crops that were transferred overland to the Mexican border towns of Matamoros and the port of Bagdad, and shipped to Europe by means of blockade runners in exchange for supplies.

Determined to close this trade, the Union mounted several invasion attempts of Texas, each of them unsuccessful. Confederate victories at Galveston, Texas, the Battle of Sabine Pass and the Second Bayou Teche Campaign repulsed invasion forces. The Union's disastrous Red River Campaign in western Louisiana, including a defeat at the Battle of Mansfield, effectively ended the Union's final invasion attempt of the region until the fall of the Confederacy. Jeffery Prushankin argues that Kirby Smith's "pride, poor judgment, and lack of military skill" prevented General Richard Taylor from potentially winning a victory that could have greatly affected the military and political situation east of the Mississippi River.[3]

Isolated from events in the east, the Civil War continued at a low level in the Trans-Mississippi theater for several months after Lee's surrender in April 1865. The last battle of the war occurred at Palmito Ranch in southern Texas from May 12–13. The battle ended in a Confederate victory.

Indian Territory

Indian Territory occupied most land of the current U.S. state of Oklahoma and served as an unorganized region set aside for Native American tribes of the Southeastern United States after being removed from their lands more than thirty years before the war. The area hosted numerous skirmishes and seven officially recognized battles[4] involving Native American units allied with the Confederate States of America, Native Americans loyal to the United States government, and Union and Confederate troops. A campaign led by Union General James G. Blunt to secure Indian Territory culminated with the Battle of Honey Springs on July 17, 1863. Though his force included Native Americans, the Union did not incorporate Native American soldiers into its regular army.[5] Officers and soldiers supplied to the Confederacy from Native American lands numbered at 7,860[5] and came largely from the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole nations.[6] Among these was Brig. Gen. Stand Watie, a Cherokee who raided Union positions in Indian Territory with his 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles regiment well after most of the Confederate forces abandoned the area. Watie led his troops in guerrilla warfare by attacking Union positions, supply wagons, and by attacking other Cherokee and Native Americans who supported the Union. He became the last Confederate General to surrender when he signed a cease-fire agreement with Union representatives on June 23, 1865.[7]

See also

Notes

- U.S. National Park Service, Civil War Battle Studies by Campaign.

- Geiger, Mark W. Financial Fraud and Guerrilla Violence in Missouri's Civil War, 1861–1865. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-300-15151-0.

- Prushankin, p. 233.

- "Civil War Sites in Oklahoma". National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- American Civil War Resource Database

- Confer, Clarissa. The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War (University of Oklahoma Press, 2007) pg.4

- "Stand Watie, Cherokee". Native American Heritage Project. June 16, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

References

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Prushankin, Jeffrey S., A Crisis in Confederate Command: Edmund Kirby Smith, Richard Taylor, and the Army of the Trans-Mississippi, Louisiana State University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-8071-3088-5.

- Prushankin, Jeffrey S., The Civil War in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, 1861-1865, United States Army Center of Military History, 2015.

- Smith, Stacey L. "Beyond North and South: Putting the West in the Civil War and Reconstruction." Journal of the Civil War Era 6.4 (2016): 566-591. online

- National Park Service campaign descriptions

- National Park Service lesson plan on Glorieta