Valley campaigns of 1864

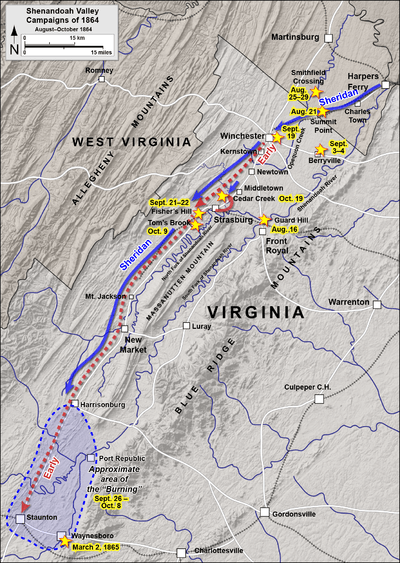

The Valley campaigns of 1864 were American Civil War operations and battles that took place in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia from May to October 1864. While some military historians divide this period into three separate campaigns, they interacted in several ways, so this article considers all three together.

Background

As 1864 began, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to lieutenant General and given command of all Union armies. He chose to make his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, although Maj. Gen. George G. Meade remained the actual commander of that army. He left Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman in command of most of the western armies. Grant understood the concept of total war and believed, as did Sherman and President Abraham Lincoln, that only the utter defeat of Confederate forces and their economic base would bring the war to an end. Therefore, scorched earth tactics would be required in some important theaters. Grant devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the heart of the Confederacy from multiple directions: he would join with Meade and Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler to fight against Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia near Richmond; Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel would invade the Shenandoah Valley and destroy Lee's supply lines; Maj. Gen. Sherman would attack Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee, invade Georgia and capture Atlanta; and finally Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks was assigned to capture Mobile, Alabama.

Lynchburg campaign (May–June 1864)

The first campaign started with Grant's planned invasion of the Shenandoah Valley from the Department of West Virginia, which Gen. Sigel commanded. West Virginia remained loyal and had been admitted to the Union, despite the Confederate Jones-Imboden Raid the previous summer. Grant ordered Sigel to move "up the Valley" (i.e., southwest to the higher elevations) with 10,000 men to destroy the Confederate railroad, hospital and supply center at Lynchburg, Virginia.

New Market (May 15)

Sigel was intercepted by 4,000 troops and cadets from the Virginia Military Institute under Confederate Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge and defeated. His forces retreated to Strasburg, Virginia. Maj. Gen. David Hunter replaced Sigel, and as discussed below would again strike southward, eventually burning VMI in retaliation for the Jones-Imboden Raid as well as subsequent actions of VMI cadets.[1]

Piedmont (June 5–6)

Hunter resumed the Union offensive and defeated William E. "Grumble" Jones at the Battle of the Piedmont. Jones died in the battle, and Hunter occupied Staunton, Virginia.[2]

On June 11 Hunter, who had continued to strike southward, fought at Lexington against John McCausland's Confederate cavalry, which retreated to the mountains and Buchanan. Hunter ordered Col. Alfred N. Duffié's cavalry division to join him in Lexington. While awaiting their arrival, Union forces burned former Governor John Letcher's home, as well as shelled and burned the Virginia Military Institute. They seized the statue of George Washington,[3] and nearly destroyed the campus (VMI moved classes to the Richmond Alms House).[4]

Joined by Duffié on June 13, Hunter sent Averell to drive McCausland out of Buchanan and capture the James River bridge. However, McCausland burned the bridge and fled. Hunter joined Averell in Buchanan on June 14 and on June 15 advanced via the road between the Peaks of Otter to occupy Liberty that evening. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge sent Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden and his cavalry to join McCausland. Breckinridge arrived in Lynchburg the next day. Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill and Brig. Gen. Harry T. Hays constructed a defense line in the hills just southwest of the city. When McCausland fell back, Averell's cavalry pursued, engaging in the afternoon Skirmish at New London Academy.[5] Union forces launched another attack on McCausland and Imboden that evening, and the Confederates retreated from New London.

Lynchburg (June 17–18)

Gen. Jubal A. Early and his troops arrived in Lynchburg on June 17 at 1 p.m. Although Hunter had planned to destroy railroads and hospitals in Lynchburg, as well as the James River Canal, when Early's initial units arrived, Hunter thought his forces outnumbered. Hunter, short on supplies, retreated back through West Virginia.[6]

Early's Washington Raid and operations against the B&O Railroad (June–August 1864)

Robert E. Lee was concerned about Hunter's advances in the Valley, which threatened critical railroad lines and provisions for the Virginia-based Confederate forces. He sent Jubal Early's corps to sweep Union forces from the Valley and, if possible, to menace Washington, D.C., hoping to compel Grant to dilute his forces against Lee around Petersburg, Virginia. Early was operating in the same area that Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson had in his successful 1862 Valley campaign. Early got off to a good start. He drove down the Valley without opposition, bypassed Harpers Ferry, crossed the Potomac River, and advanced into Maryland. Grant dispatched a corps under Horatio G. Wright and other troops under George Crook to reinforce Washington and pursue Early.

Monocacy (July 9)

Early defeated a smaller force under Lew Wallace near Frederick, Maryland, but this battle delayed his progress enough to allow time for reinforcing the defenses of Washington.[7]

Fort Stevens (July 11–12)

Early attacked a fort on the northwest defensive perimeter of Washington without success and withdrew back to Virginia.[8]

Heaton's Crossroads (July 16)

Union cavalry attacked Early's supply trains at Purcellville as the Confederates withdrew across the Loudoun Valley towards the Blue Ridge Mountains. Several small cavalry skirmishes occurred throughout the day as the Federals attempted to harass Early's column.[9]

Cool Spring (July 17–18)

Also known as Snicker's Ferry. Early attacked and repulsed pursuing Union forces under Wright.[10]

Rutherford's Farm (July 20)

A Union division attacked a Confederate division under Stephen Dodson Ramseur and routed it. Early withdrew his army south to Fisher's Hill, near Strasburg, Virginia.[11]

Second Kernstown (July 24)

Wright withdrew, thinking Early was no longer a threat. Early attacked him to prevent or delay his return to Grant's forces besieging Petersburg. Union troops were routed, streaming through the streets of Winchester. Early pursued and burned Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, along the way in retaliation for Hunter's previous destruction in the Valley.[12]

Folck's Mill (August 1)

Also known as the Battle of Cumberland. An inconclusive small cavalry battle in Maryland.[13]

Moorefield (August 7)

Also known as the Battle of Oldfields. Confederate cavalry returning from the Chambersburg burning were surprised in the early morning and defeated by Union cavalry.[14]

Sheridan's Shenandoah Valley campaign (August–October 1864)

Grant finally lost patience with Hunter, particularly his allowing Early to burn Chambersburg, and knew that Washington remained vulnerable if Early was still on the loose. He found a new commander aggressive enough to defeat Early: Philip Sheridan, the cavalry commander of the Army of the Potomac, who was given command of all forces in the area, calling them the Army of the Shenandoah. Sheridan initially started slowly, primarily because the impending presidential election of 1864 demanded a cautious approach, avoiding any disaster that might lead to the defeat of Abraham Lincoln.

Guard Hill (August 16)

Also known as Front Royal or Cedarville. Confederate forces under Richard H. Anderson were sent from Petersburg to reinforce Early. Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt's Union cavalry division surprised the Confederate columns while they were crossing the Shenandoah River, capturing about 300. The Confederates rallied and advanced, gradually pushing back Merritt's men to Cedarville. The battle was inconclusive.[15]

Summit Point (August 21)

Also known as Flowing Springs or Cameron's Depot. Early and Anderson struck Sheridan near Charles Town, West Virginia. Sheridan conducted a fighting withdrawal.[16]

Smithfield Crossing (August 25–29)

Two Confederate divisions crossed Opequon Creek and forced a Union cavalry division back to Charles Town; Confederate offensive against the city was then repulsed and their advance permanently halted.[17]

Berryville (September 3–4)

A minor engagement in which Early attempted to stop Sheridan's march up the Valley. Early withdrew back to Opequon Creek when he realized he was in a poor position for attacking Sheridan's full force.[18]

Third Winchester (September 19)

.png)

Also known as the Battle of Opequon. After learning from Quaker Unionist Rebecca Wright that Early had dispersed his forces to raid the B&O Railroad and had removed infantry and artillery from nearby Winchester, Virginia (an important town and transportation center that changed hands 75 times in the war), Sheridan attacked Early's camp at Opequon Creek just outside the town. Sustaining ruinous casualties, Early retreated from the largest battle in all three of the campaigns, taking up defensive positions at Fisher's Hill.[19]

Fisher's Hill (September 21–22)

Sheridan hit Early in an early-morning flanking attack, routing the Confederates with moderate losses. Early retreated to Waynesboro, Virginia.[20]

With Early damaged and pinned down, the Valley lay open to the Union. And because of Sherman's capture of Atlanta, Lincoln's re-election now seemed assured. Sheridan pulled back slowly down the Valley and conducted a scorched earth campaign that would presage Sherman's March to the Sea in November. The goal was to deny the Confederacy the means of feeding its armies in Virginia, and Sheridan's army did so ruthlessly, burning crops, barns, mills, and factories.

Tom's Brook (October 9)

As Early began a pursuit of Sheridan, Union cavalry routed two divisions of Confederate cavalry.[21]

Cedar Creek (October 19)

In a surprise attack, Early smashed two thirds of the Union army, but his troops were hungry and exhausted and fell out of their ranks to pillage the Union camp; Sheridan, in a ride from Winchester, managed to rally his troops and utterly rout Early's men, and the Confederates lost everything they had gained in the morning. This victory helped Lincoln get reelected.[22]

Aftermath

After his missions of neutralizing Early and suppressing the Valley's military-related economy, Sheridan returned to assist Grant at Petersburg. Most of the men of Early's corps rejoined Lee at Petersburg in December, while Early remained to command a skeleton force. His final action was defeat at the Battle of Waynesboro on March 2, 1865, after which Lee removed him from his command because the Confederate government and people had lost confidence in him.

See also

Notes

- NPS New Market

- NPS Piedmont

- "Hunter's Raid, Civil War Travels website". Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- VMI Archives

- http://www.newsadvance.com/news/local/civil_war/battle_of_lynchburg/brunch-at-new-london-helped-delay-union-march/article_a1e07efe-f255-11e3-95d5-0017a43b2370.html

- NPS Lynchburg

- NPS Monocacy

- NPS Fort Stevens

- Patchan, pp. 45-60.

- NPS Cool Spring

- NPS Rutherford's Farm

- NPS Kernstown II

- NPS Folck's Mill

- NPS Moorefield

- NPS Guard Hill

- NPS Summit Point

- NPS Smithfield Crossing

- NPS Berryville

- NPS Opequon

- NPS Fisher's Hill

- NPS Tom's Brook

- NPS Cedar Creek

References

- Gallagher, Gary W., ed. Struggle for the Shenandoah: Essays on the 1864 Valley Campaign. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-87338-429-6.

- Patchan, Scott C. Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8032-3754-4.

- National Park Service battle descriptions

Further reading

- Cooling, Benjamin Franklin. Jubal Early's Raid on Washington, 1864. Baltimore: Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America, 1989. ISBN 0-933852-86-X.

- Davis, Daniel T., and Phillip S. Greenwalt. Bloody Autumn: The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2013. ISBN 978-1-61121-165-8.

- Early, Jubal A., "General Jubal A. Early tells his story of his advance upon Washington, D.C.". Washington National Republican, 1864.

- Early, Jubal A. A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence in the Confederate States of America. Edited by Gary W. Gallagher. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2001. ISBN 1-57003-450-8.

- Gallagher, Gary W., ed. The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864. Military Campaigns of the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-8078-3005-5.

- Janda, Lance. "Shutting the gates of mercy: The American origins of total war, 1860-1880." Journal of Military History 59#1 (1995): 7-26. online

- Lewis, Thomas A., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Shenandoah in Flames: The Valley Campaign of 1864. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1987. ISBN 0-8094-4784-3.

- Patchan, Scott C. The Last Battle of Winchester: Phil Sheridan, Jubal Early, and the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, August 7–September 19, 1864. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2013. ISBN 978-1-932714-98-2.