Cherokee Commission

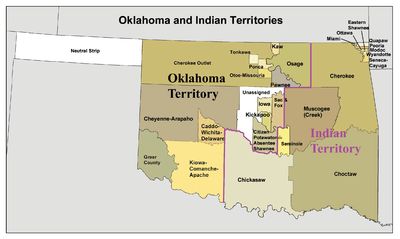

The Cherokee Commission, was a three-person bi-partisan body created by President Benjamin Harrison to operate under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, as empowered by Section 14 of the Indian Appropriations Act of March 2, 1889. Section 15 of the same Act empowered the President to open land for settlement. The Commission's purpose was to legally acquire land occupied by the Cherokee Nation and other tribes in the Oklahoma Territory for non-indigenous homestead acreage.

Eleven agreements involving nineteen tribes were signed over the period of May 1890 through November 1892. The tribes resisted cession. Not all understood the terms of the agreements. The Commission tried to dissuade tribes from retaining the services of attorneys. Not all interpreters were literate. Agreement terms varied by tribe. As negotiations with the Cherokee Nation snagged, the United States House Committee on Territories recommended bypassing negotiations and annexing the Cherokee Outlet.

The Commission continued to function until August 1893. Lawsuits, Supreme Court rulings, investigations and mandated compensation for irregularities ensued through the end of the 20th Century. Congress failed to respond to a legal protest from the Tonkawa, or to an Indian Rights Association investigation that condemned the Commission's actions with the Cheyenne and Arapaho. Commission attempts to negotiate signed agreements produced no results with the Osage, Kaw, Otoe and Ponca.

The 1887 Dawes Act[1] empowered the President of the United States to survey commonly held tribal lands and allot the land to individual tribal members, with the individual land patents to be held in trust as non-taxable by the government for 25 years.

Indian Appropriations Act

On March 2, 1889, President Grover Cleveland signed the Indian Appropriations Act into law. Section 14 of the Act authorized the President to appoint a three-person bi-partisan commission to negotiate with the Cherokee and other tribes in Indian Territory for cession of their lands to the United States. Benjamin Harrison became President on March 4.[2][3] The body was officially named the Cherokee Commission, and its existence ended in August 1893.[4][5][6] Section 15 of the same Act empowered the President to open land for settlement.[2] On May 2, 1890, President Harrison signed into law the Oklahoma Organic Act creating the Oklahoma Territory.[7][8][9]

On July 1, 1889, the Commission received its initial funding. Food, transportation and lodging were all compensated, plus $5 per diem. The commissioners received an additional $10 per diem while they were actually in service.[10] Congress appropriated an additional $20,000 for the Commission to continue its work.[11] In 1892, Congress appropriated another $15,000 for the Commission.[12] March 1893, Commission got $15,000 additional appropriation.[13]

Commission organization

The Cherokee Commission was to operate under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, John Willock Noble, and his successor, Michael Hoke Smith. Noble's directive to the Commission was to offer $1.25 per acre, but to adjust that amount if the situation favored it.[10] Lucius Fairchild of Wisconsin was appointed the first Chairman of the Commission.[14] Fairchild submitted his resignation to President Harrison after the committee's first endeavor failed in negotiations with the Cherokee.[15][16] Angus Cameron of Wisconsin was appointed to replace Fairchild as Chairman of the Commission, and resigned after three weeks. David H. Jerome of Michigan was appointed to fill the chairman vacancy.[17] The lone Democrat on the Commission was Judge Alfred M. Wilson of Arkansas.[18] John F. Hartranft, recipient of the Medal of Honor[19] and former Governor of Pennsylvania, became the initial third person on the committee.[14] Hartranft died on October 17, 1889.[20] President Harrison appointed his friend Warren G. Sayre of Indiana to replace Hartranft.[21]

Tribal agreements with the Commission

Iowa – May 20, 1890

The Iowa tribe is believed to have originated in Wisconsin. To avoid white settlers on their lands, the tribe moved to Iowa and Missouri, but later ceded their land and relocated to the Kansas-Nebraska border. In 1878, the full-bloods of the tribe moved to Indian Territory.[22]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Col. S.L. Patrick, the total Iowa reservation population was counted at 102.[23] Reservation acreage was reported as 225,000 acres (910 km2; 352 sq mi), west of the Sac and Fox reservation with comparable land. The population had members who were conversant in the English language, and some wore what was termed "citizens' clothes". Income was estimated at $50 per capita annually.[24]

Lucius Fairchild and the Commission approached the Iowa on October 18, 1889, and were rebuffed.[25] In May 1890, the Commission under David H. Jerome returned for negotiations, notifying the tribe of an October cessation to cattle grazing leases. Jerome told them the President was offering individual homesteads, and offering to take the resulting surplus land off their hands. Chief William Tohee stood firm that the Iowa preferred to keep their entire reservation for future generations. Jerome warned that failure to acquiesce would force the government to employ the Dawes Act. The Iowa felt that allotment and money was not good for the tribe, and they were still awaiting past government monies owed them. Many Iowa expressed concern about their children's forced assimilation in white schools, and were distrusting of the government. The Commission reiterated the threat of forced Congressional allotments. Jefferson White Cloud announced that the Iowa would sign the agreement.[26]

On May 20, 1890, at the Iowa Village on their reservation, the tribe signed the Agreement with the Iowa (1890) to cede all their land, in return for $60,000 (less than 27 cents per acre) divided per capita and paid in five installments, spread out over a 25-year period. The allotment was 80 acres (0.32 km2; 0.13 sq mi) per person. Land patents to the individual land allotted were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. The allotments were to be selected by the individual tribal members within 60 days of government agents initiating the process. If any member failed to make the selection within that time frame, the selection would be made for them by the special agent. Article IX of the agreement addressed the frail situation with Chief William Tohee and his wife Maggie. Due to his blindness and advanced age, the childless couple were to be paid $350 for their care and well-being. Tribal member Kirwan Murray acted as interpreter. Congress ratified the agreement on February 13, 1891.[27]

In 1929, the United States Court of Claims rendered a judgment that the tribe had been underpaid, due to irregularities. The tribe was awarded $254,632,59.[28]

Sac and Fox – June 12, 1890

The Sac and Fox Nation in Oklahoma. also called Sauk and Fox, were moved to Indian Territory as a result of Article 6, in the Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes (1867).[29] In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Col. S.L. Patrick, the total Sac and Fox reservation population was counted at 515. Reservation acreage was reported as 479,667 acres (1,941.14 km2; 749.480 sq mi), juxtaposed between the Cimarron, North Fork and Canadian rivers. It was in use as grazing, farming and orchards.[23] Living conditions were reported as tipis or bark houses, with their main clothing being blankets. The Fox and Sac National Council was credited with uplifting the morality of the tribe by prohibiting polygamy, and requiring lawful marriages.[24]

The Commission under Lucius Fairchild first met Moses Keokuk and the Sac and Fox in October 1889. Fairchild offered the tribe its choice of land for the allotments, and $1.25 per acre for surplus land.[30] When Jerome assumed the Chairmanship, the Commission returned for negotiations on May 28, 1890. Principal chief Maskosatoe was in attendance, but Keokuk, who spoke no English, led the tribal negotiations through an interpreter. Keokuk inquired about the allotment acreage and how much land the Commission wanted them to cede. Jerome cited the Dawes Act allotment directive of 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi) to heads of household, 80 acres (0.32 km2; 0.13 sq mi) for single persons over 18 years of age, and 40 acres (0.16 km2; 0.063 sq mi) for persons under 18 years of age. Keokuk countered with 200 acres (0.81 km2; 0.31 sq mi) per person and a cession at $2.00 per acre. Jerome balked at the suggestion. Keokuk and the Sac and Fox National Council forced the Commission to agree to 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi) per person, regardless of age or marital status. The twist was that the Commission required land patents for only half the per person acreage to be held in trust for 25 years, with the other half held in trust for only 5 years. The deal would allow tribal members to sell half their acreage after 5 years.[31]

At the seat of government of the Sac and Fox Nation, the tribe signed the Agreement with the Sauk and Fox (1890) on June 12, 1890 to cede their land in return for $485,000 (slightly over $1 per acre). $300,000 of the total payment was to be placed in the United States Treasury, $5,000 to be paid to the local Indian agent to be expended under the direction of the National Council of the Sac and Fox, and the remaining $180,000 to be paid per capita within three months of Congressional ratification of the agreement. The allotments were to be selected by the individual tribal members within four months of allotting agents arriving to begin the process. If any member failed to make the selection within that time frame, the selection would be made for them by the local agent. The number of allotments was limited to 528, and any allotment over that limit would result in $200 per excess allotment being deducted from the $485,000. Congress ratified the agreement on February 13, 1891.[32]

In 1964, in response to an appeal of the tribal claim, the United States Court of Claims ruled the tribe had been underpaid, and awarded them $692, 564.14.[33]

Citizen Band of Potawatomi – June 25, 1890

The Citizen Band of Potawatomi were so named because of the Treaty with the Potawatomi (1887), which promised the band full citizenship in exchange for their agreement to move to a reservation.[34] In 1872, the United States Congress authorized the Potawatomi reservation to be in Indian Territory.[35]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Col. S.L. Patrick, the total Citizen Band of Potawatomi reservation population was counted at 480.[23] The reservation was reported at 575,000 acres (2,330 km2; 898 sq mi), most of it between Little River and the South Canadian.[24] The band were reported as having white blood, almost all conversant in both written and spoken knowledge of the English language. They were reported as a wealthy populace. Allotments assigned by N.S. Porter had been happening for two years.[36]

On June 25, 1890, at Shawneetown, the tribe signed the Agreement with the Citizen Band of Potawatomi (1890) and ceded their 575,870.42 acres (2,330.4649 km2; 899.79753 sq mi) for $160,000 (slightly less than 28 cents per acre) . An attorney had been engaged for the tribe during the negotiations.[37] Many Potawatomi allotments had already been done in accordance with the Dawes Act. Land patents to the individual land allotted were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. Those allotments, added to additional allotments were limited to a total of 1,400. The agreement stated that if additional allotments were needed, that $1 for each acre of land needed was to be deducted from the $160,000 paid the tribe, and divided per capita, for its land cession. After February 8, 1891, right to allotment ceased. Tribal member Joseph Moose acted as interpreter. Congress ratified the agreement on March 3, 1891.[38]

In 1968, the Indian Claims Commission awarded the Potawatomi $797,508.99, as part of its ruling that the land sold in 1890 had actually been worth $3 an acre.[39]

Absentee Shawnee – June 26, 1890

The Treaty with the Shawnee (1825) provided for a reservation in Kansas.[40] The Shawnee who were living on the Oklahoma Potawatomi reservation were given the name Absentee-Shawnee, because they were absent from the Shawnee reservation in Kansas.[41]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Col. S.L. Patrick, the total Absentee-Shawnee population was counted at 640.[23] Their acreage was reported as being part of the Potawatomi reservation, on fertile ground between the North Fork and Canadian rivers. They were reported as having advanced to what was considered civilized clothing, living in log houses, and owning livestock. Populace was split between two bands. The Lower Shawnee under Chief White Turkey and the Upper Shawnee under Big Jim. Allotments assigned by N.S. Porter had been happening for two years.[36]

On June 26, 1890, at Shawneetown, The Absentee-Shawnee signed the Agreement with the Absentee Shawnee (1890) and ceded 578,870.42 acres (2,342.6055 km2; 904.48503 sq mi) for $65,000 (less than 11 cents an acre).[37] Big Jim of the Upper Shawnee refused to sign the agreement.[39] The Shawnee allotments were done in accordance with the Dawes Act, and limited to 650 allotments, including the allotments made prior to the agreement. If additional allotments over 650 were made, $1 for each acre of land therein was to be deducted from the $65,000 paid the tribe. Tribal members had until January 1, 1891 to select their allotments. If any member failed to make the selection within that time frame, the selection would be made for them by the local agent by February 8, 1891. After that date, right to allotment ceased. Land patents to the individual land allotted were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. Tribal member Thomas W. Alford acted as interpreter. Congress ratified the agreement on March 3, 1891.[42]

In 1999, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that only the Potawatomi had proprietary rights to the reservation land ceded in 1890, so the Absentee-Shawnee were unable to share in the 1968 award for under payment.[43]

Cheyenne and Arapaho – October 1890

The 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie set the Cheyenne and Arapaho boundaries as between the North Platte and the Arkansas rivers in Colorado. The 1861 Treaty of Fort Wise ceded most of the tribal land from the 1851 treaty.[44] In the 1865 Treaty of Little Arkansas, the tribes were removed to the southern boundary of Kansas.[45] The Treaty of Medicine Lodge, signed by the southern Arapaho and Cheyenne on October 28, 1867, assigned the two tribes to live on the same reservation within the Cherokee Outlet, and also stipulated that any land cession required the signature of three-fourths of all the adult males of the reservation population.[46][47]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Charles F. Ashley, the total reservation population was Cheyenne 2, 272 and Arapaho 1,100. There had been much trouble with the Dog Soldiers preventing rations being issued to those who allowed their children to be enrolled in school.[48]

The Ghost Dance religion, as practiced by a Northern Paiute named Wovoka made its influence felt among the Arapaho at this time. Wovoka was the son of a prophet named Tavibo, and according to historian James Mooney, was considered "The Messiah" of the Ghost Dance.[49] The Cheyenne first learned about this Messiah in 1889. He was alleged to live near the Shoshone in Wyoming and would bring back the buffalo and remove the white people from tribal land. A delegation led by Porcupine was sent to observe the Ghost Dance. In his account upon their return, Porcupine had become a full believer in both the Messiah and the dance. When questioned by the military authority, Porcupine gave a total accounting, but Mooney notes that in his enthusiasm, Porcupine might have embellished a bit.[50] Some abandoned their work in favor of the dancing. Agent Ashley tried to put a halt to it.[51]

On July 5, 1890, the Commission held a preliminary meeting with Old Crow, Whirlwind and Little Medicine, all opposed to cession. Jerome received instructions from Noble to follow the Treaty of Medicine Lodge directive in getting three-fourths of adult males to sign the agreement. On July 7, the Commission opened negotiations with the 1887 Dawes Act, which empowered the President to make allotments. The tribes refused to negotiate, citing their land as having been given to them by the Great Spirit and by the terms of the Treaty of Medicine Lodge. At the July 9 meeting, Sayre presented the Commission's proposal and told the tribes they, "...will be the richest people on earth." The crowd balked.[52] On July 14, Jerome threatened the government's right to cut off rations. The Cheyenne began boycotting the sessions on July 15. Both Jerome and Sayre threatened them with the Dawes Act.[53] On July 21, the Arapaho Army scouts walked out of the negotiations.[54]

Jerome, Sayre and Noble met in New York to agree on requests for the President: 1) Amend the Dawes Act to implement a time limit for acceptance; 2) Forbid outside cattle on the land; and 3) Cancel the attorney contracts if the attorneys were influencing the tribal resistance.[55] Noble learned that Cheyenne chiefs Whirlwind, Old Crow, Little Medicine, Howling Wolf and Little Big Jake were in disagreement with the Commission over the attorney contract. On October 7, the Cheyennes boycotted the negotiations, and the Arapaho refused to continue.[56]

Collecting of signatures began in Darlington, on October 13. By November 12, Noble declared sufficient signatures for the Agreement with the Cheyenne and Arapaho (1890). Tribal members complained of fraud, citing signatures of women and underage males counted. It was also alleged that rather than counting the number of signatures separately by tribe, the Commission had used the aggregate total halved.[57] Under the terms of the agreement signed October 1890, the tribes were to receive $1,500,000. Two payments were to be $250,000 each, and the remaining $1,000,000 to be retained by the Treasury of the United States at five percent interest. Allotments of 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi) per person were to be selected by the individual tribal members within 90 days of Congressional ratification of the agreement. Failed to make the selection within the time frame, would cede selection for them to the local agent. Land patents to the individual land allotted were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. Congress ratified the agreement on March 3, 1891.[58]

Tribal attorneys

Former Indian agents John D. Miles and D.B. Dwyer, Secretary Noble's law firm associate M.J. Reynolds, and former Kansas Governor Samuel J. Crawford were contracted by the tribes, and approved by Secretary Noble, to represent the Cheyenne and Arapaho.[59] Their original fees were 10% of the cession agreement, deducted from the second cash installment paid to the tribes.[60] Jerome questioned the wisdom of having attorneys whom the tribes distrusted as acting solely in the government's interest. Noble and the attorneys revised their contracts to adjust the 10% commission to a sliding scale.[56] When the tribes refused to deal with contracted attorneys, the team of lawyers mainly assisted with the gathering of signatures to approve the contract.[61] The government deducted $67,000 for attorneys fees from the 1892 second installment payment to the Cheyenne and Arapaho.[62]

Tribal claims

The deduction for attorney fees, led the tribes to address the grievance to the government. Among their supporters were John H. Seger, former Indian agent Captain J.M. Lee, and Charles Painter of the Indian Rights Association. Painter's investigative findings were published by the Indian Rights Association in 1893 as Cheyennes and Araphos Revisited and a Statement of Their Contract with Attorneys. Therein, Captain Lee accused the contractual arrangement as being "...misrepresentation, fraud and bribery." Painter also accused the attorneys of bribery, and of causing the tribes to lose three-fourths of the value of their land. As a result of the investigation, Congress did nothing. In 1951, the tribes brought suit against the United States, through the Indian Claims Commission. The findings were that the 51,210,000 acres (207,200 km2; 80,020 sq mi) involved were worth $23,500,000 at the time of the agreement. The tribes reached a settlement with the government in the amount of $15,000,000.[62][63]

Wichita and affiliated bands – June 4, 1891

Article 9 of the Treaty with the Choctaw and Chickasaw (1855) provided for the United States to lease the area between the 98th and 100th Meridians and the South Canadian River and Red River, for the purpose of permanent settlement of the Wichita and other tribes, and became officially titled the Leased District.[64][65] After the Civil War, Article 3 of the Treaty with the Choctaw and Chickasaw (1866) ceded the Leased District to the United States for the sum of $300,000.[66][67] In 1867, the Kiowa and Comanche received reservations in the district. In 1868, the Wichita and Caddo received district reservations. The Cheyenne and Arapaho received district reservations in 1869.[68][69] Because the Wichita felt threatened by having these other tribes so near to them, in 1872 the government negotiated an agreement with the Wichita to increase their own reservation to 743,610 acres (3,009.3 km2; 1,161.89 sq mi). The agreement was never ratified by Congress, and the Wichita claim to the acreage would become a point of legal dispute with the Choctaw and Chickasaw upon the signing of the Commission agreement with the Wichita.[70][71]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Charles E. Adams, the total Wichita reservation population of 991 was divided into six bands: 174 Wichitas, 538 Caddo, 150 Tawakoni, 66 Kichai, 95 Delaware and 34 Waco.[72]

The Commission opened negotiations with the Wichita on May 9, 1891, by presenting the dictates of the Dawes Act, and asking the Wichita to commit to cession. David Jerome was immediately challenged by Tawakoni Jim, who argued for an attorney to represent the tribes. Jerome tried to dissuade the idea as a waste of money and time. Tawakoni Jim also challenged the acreage being offered under allotments. Caddo Jake stated that the priority should be educating the children before any negotiations could take place.[73] Comments from tribal members reflected on the distrust of the government's word, based on broken treaty promises of the past. Caddo Jake made reference to the indigenous people's experience with Christopher Columbus, which provoked a retort from Jerome that Christopher Columbus had never been on the North American continent. Caddo Jake would also draw the parallel between the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and the American tribes. Sayre presented a Commission proposal that was the standard 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi) allotment, and a payment of $286,000 for surplus land. The crowd pressed for the price per acre, and Sayre finally conceded they were offering the Wichita only 50 cents per acre. When it became evident that the Wichita would not negotiate without an attorney, the government produced Luther H. Pike to represent them.who had persuaded [74] Eventually, Pike and the Wichita agreed to the Commission's terms, with the exception of the price per acre. Jerome agreed to allow Congress to set the price.[75]

On June 4, 1891 at Anadarko, the Agreement with the Wichita and Affiliated Bands (1891) ceded their surplus land, with Congress setting the price per acre. Allotments were 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi), and limited to a total 1,060 allotments. Each allotments in excess of that amount was to reduce the total amount Congress approved for payment of the surplus land. The allotments were to be selected by the individual tribal members within 90 days of Congressional ratification of the agreement. If any member failed to make the selection within that time frame, the selection would be made for them by the local agent. Land patents to the individual land allotted were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. Interpreters Cora West and Robert M. Dunlap attested to having fully interpreted the terms of the agreement to the tribes before signing began. Congress ratified the agreement March 2, 1895.[76]

In 1899, the Court of Claims rendered a judgment, that only the Choctaw and Chicksaw were entitled to the payment for the surplus land. The Wichita appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which overturned the ruling. The Court of Claims awarded the Wichitas $673.371.91 ($1.25 an acre) for their surplus land. When Congress finally appropriated the funding in 1902, it deducted 43,332.93 from the total payment for attorney fees.[77]

Kickapoo – September 9, 1891

The nomadic Kickapoo were first known to inhabit Michigan, and by the 19th Century were split between Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. The Texas band migrated to Mexico.[78] In 1873, Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie, under orders from General Philip H. Sheridan, raided the Kickapoo camps in Mexico. The captured Kickapoo were forcibly removed to Indian Territory.[79]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Col. S.L. Patrick, the total Kickapoo reservation population was counted at 325.[23] Reservation acreage was reported as approximately200,000 acres (810 km2; 310 sq mi), west of the Sac and Fox reservation. It was reported that $5,000 was appropriated annually for basic medical care, supplies and farming implements. The population was reported as good farmers.[24]

The Kickapoo were first approached by the Commission, with Lucius Fairchild as Chairman, in October 1889. The tribe was not interested in allotments.[80] On June 27, 1890, the Commission under Jerome returned to negotiate with the Kickpoo. The tribe had since been under advisement by Cherokee Chief Joel B. Mayes, and once again rebuffed the Commission.[81] In June 1891, the Commission returned to negotiate with the tribe. The Kickapoo refused to anger the Great Spirit by ceding their land.[82]

Jerome moved the negotiations to Washington, D.C. Okanokasie, Keshokame and five headmen were authorized to represent the tribe. A white man named John T. Hill acted as tribal advisor.[83] On September 9, 1891 in Washington, D.C., the Kickapoo signed the Agreement with the Kickapoo (1891) to cede their lands for $64,650 (about 32 cents per acre). Their allotments were 80 acres (0.32 km2; 0.13 sq mi) per person. and not to exceed a total of 300 allotments. Each allotment over the 300 limit would result in $50 being deducted from the $64,650 paid to the tribe. The allotments were to be selected by the individual tribal members within 90 days of Congressional ratification of the agreement. If any member failed to make the selection within that time frame, the selection would be made for them by the local agent. Land patents to the individual allotments land were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. Joseph Whipple, testified that he was chosen by the Kickapoo as interpreter because of his fluency with the tribal language. He also attested that he was neither able to read nor write, and that what he conveyed to the Kickapoo was a translation of what had been read to him by Sayre. Congress ratified the agreement March 1893.[84]

Quaker field matron Elizabeth Test reported in August 1894, that most Kickapoo did not understand that the agreement meant they were giving up their land. With the assistance of advocate Charles C. Painter of the Indian Rights Association, the Kickapoo presented their case to the House Committee on Indian Affairs Painter alleged the Commission had used, "trickery, coercion, threats and cunning," and had also, "over-reached and defrauded" the Kickapoo. In 1908, Congress appropriated another $215,000 for the tribe, but deducted $26, 875 for payment of the services of a Martin J. Bentley.[85]

Tonkawa – October 21, 1891

Originally a Texas tribe, the Tonkawa came close to extinction with the dwindling herds of buffalo. In 1859, the United States government moved them to the Leased District in Indian Territory. During the Civil War, the tribe aligned with the Confederacy. In 1862, the Tonkawa Massacre decimated the tribe.[86] In 1885, the Tonkawa relocated to the Outlet in the area currently known as Kay County and served as scouts for the United States Army.[87] The land had been conveyed by the Cherokee Nation in 1883 to the United States, to be held in trust for the Nez Perce, and later abandoned by the Nez Perce when they returned to their homeland.[88]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent D.J.M. Wood, the total Tonkawa reservation population was counted at 76. Of this number, 14 were school children. They were described as a group who dressed in the white society's attire and attempted to speak only English. Many in the populace were identified as retired Government scouts and their wives. The agent stipulated these people should be cared for, in recognition of their government service. The only problem reported was alcohol and mescal bean addiction. The report called the Tonkawa "ready and anxious" to accept allotments.[89]

On October 21, 1891 at the Ponca Indian Agency, the Tonkawa signed the Agreement with the Tonkawa (1891) to cede their entire 90,710.89 acres (367.0939 km2; 141.73577 sq mi) to the United States government, in return for $30, 600 (approximately 34 cents an acre). $25 was to be paid in cash to each person within sixty days of ratification by Congress. An additional $50 was to be paid to each tribal member within six months of ratification. The remainder of the money was to be held in trust at the United States Treasury at 5% per annum, payable annually. Sixty-nine allotments of land were agreed to, plus a like allotment for any future tribal member born after the agreement was signed, but alive by the date of Congressional ratification. Land patents to the individual land allotted were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. Peter Dupee, adopted member of the Tonkawa tribe, acted as interpreter. Congress ratified the agreement on February 3, 1893.[90]

The Tonkawa hired legal counsel and claimed they had been pressured into signing the agreement, under the threat that all their allotments would be canceled if they failed to capitulate. They claimed they had demanded $1.25 per acre. Congress failed to act on their claim.[91]

Cherokee – December 1891

During the 1836–1839 Cherokee removal from all tribal lands west of the Mississippi, the tribe signed the 1835 Treaty of New Echota that created their reservation in Oklahoma, "including the Outlet" specifically named as part of the Cherokee reservation.[92] The acreage west of the 96th Meridian was known as the Cherokee Outlet, or Cherokee Strip. When cattlemen began leasing grazing land on the Outlet, the Cherokees levied taxes on the cattlemen. Some of the cattlemen ignored the levies, and began building fences made of Outlet timber. In 1883, the Interior Department forced removal of the fences. The cattlemen formed the Cherokee Strip Livestock Association to work with the tribes.[93]

Tribal chief Joel B. Mayes was a graduate of Cherokee Male Seminary, a former school teacher, and a veteran of the Confederate First Indian Regiment during the Civil War. Before and after the war, Mayes ran a farm, oversaw his fruit orchards, and raised livestock.[94] In 1883, he was elevated to Chief Justice of the Cherokee Supreme Court, and became Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation in 1888. Mayes was responsible for renegotiation of the grazing lease on the Outlet.[95] He was re-elected as Chief in 1891, and died on December 14 of that year.[96] Upon his death, Colonel Johnson Harris was elected chief.[97]

At the Commission's organizational meeting on July 1, 1889, Interior Secretary Noble directed the Commission to begin negotiations with the Cherokees for cession of the Outlet.[10] The majority of Cherokees did not want to sell the Outlet land, and Chief Mayes was focused on potential increase in tribal income by hiking taxes to cattlemen.[98] Lucius Fairchild and the Commission first arrived in Tahlequah on July 29, and made an offer for the Outlet on August 2.[99] Commission efforts did not bear fruition, and the Cherokees were notified on December 27, 1889, that the Commission's offer was to be withdrawn.[16] At the urging of Noble and Fairchild, President Harrison issued a proclamation on February 17, 1890 banning all cattle and livestock from the Outlet, and ordering removal of any existing cattle and livestock no later than October 1, 1890, eliminating Cherokee income from the Outlet.[100][101]

In November 1890, with Jerome as Chairman, the Commission returned to resume negotiations. Empowered by the Cherokee National Council, Mayes appointed a nine-member committee: Stan W. Gray as Chairman, William P. Ross, Johnson Spade, Rabbit Bunch, L.B. Bell, Stephen Tehee, John Wickliffe, Arch Scrapper and George Downing. E. C. Boudinot acted as clerk, and Captain H. Benge acted as interpreter.[102] By December 26, 1890, the negotiations once again aborted with no results.[103]

The United States House Committee on Territories recommended in February 1891 bypassing negotiations and annexing the Outlet, paying the Cherokees $1.25 an acre as a settlement. In the Oklahoma Territory, judges ruled that the Cherokees had no legal ownership of the Outlet. Cherokee delegates submitted documentation as proof of Outlet ownership. The Commission re-opened negotiations with the Cherokees in November 1891.[104] The Commission presented its basic proposal to the tribe. The Cherokees requested the boundary of the Outlet be moved from the 96th to the 100th Meridian, and that the government estimate the acreage involved in the negotiations. A main point of contention in the negotiations was the question of intruders, outside workers residing on Cherokee land, and the history of the United States failing to handle the problem. The Cherokee Nation presented a counter-proposal that called for $3 an acre. Both Jerome and Sayre ridiculed the Cherokee proposal. The Commission threatened that Congress could remove the tribe from Trade and Intercourse acts.[105] On December 11, the Commission and the tribe came close to terms, with the Cherokees asking for $2 an acre. E. C. Boudinot continued to debate with the Commission over details, and said the tribe had a copy of the 1889 Indian Office's instructions to the Commission.[106]

On December 19, a compromise was reached.[107][108] The Agreement with the Cherokee (1891) was ratified by the Cherokee National Council at Talequah on January 4, 1892. The Cherokees ceded 8,144,682.91 acres (32,960.3623 km2; 12,726.06705 sq mi), for $8,595,736.12.[109] Congress ratified the agreement on March 4, 1893.[110]

In 1961, the Indian Claims Commission awarded the Cherokee Nation $14,364,476.15 compensation for underpayment by the government. The commission ruled that the land had actually been worth $3.75 an acre in 1892.[111]

Comanche, Kiowa and Apache – October 6–21, 1892

On October 21, 1867, the Kiowa and Comanche tribes signed the Treaty of Medicine Lodge, which removed them to a shared reservation in Indian Territory, and also stipulated that any land cession required the signature of three-fourths of all the adult males of the reservation population.[112][113] Not all tribal members immediately went to the reservation. Many continued to live on the plains, only brought to conformity by the Red River War campaign. Quanah Parker and his Quahada Comanche band surrendered near Fort Sill on June 2, 1875.[114] Two years later, Parker was responsible for bringing a renegade band of Comanches to surrender.[115] Once on the reservation, Parker became wealthy through cattle leasing. He was paid $35 a month by cattlemen as their spokesperson, and sent to Washington D.C. to represent them.[116] The cattlemen also helped finance the building of Parker's eight-bedroom two-story reservation Star House.[117]

In the August 1892 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent George D. Day, the total reservation population was counted as Kiowa 1,014, Comanche 1,531 and Apache 241.[118]

The Commission opened negotiations with the Kiowa, Comanche and Apache at Fort Sill on September 26, 1892.[119] Jerome made an opening presentation, and Quanah Parker asked specifically how much money per acre, and what were the terms offered. Jerome stalled on the details of money. Other tribal members preferred to defer the negotiations until the Treaty of Medicine Lodge expired. At the next day's session, Parker continued to press Jerome for financial details, as Jerome avoided discussing the money. Sayre detailed the overall offer of $2,000,000 and per capita distribution. Parker once again asked how much per acre.[120] Sayre didn't have an answer, and Parker asked him how he arrived at $2,000,000. To that, Sayre replied, "...we just guess at it." Parker stated that he had heard about price per acre differential between the various tribal agreements. Lone Wolf added that many wanted to defer until the expiration of the Medicine Lodge treaty.[121]

On October 3, Wilson cited the 1887 Dawes Act, reminding the tribes that the government could force allotment on them. Parker proposed one elected representative from each tribe meet with an attorney of his choosing, with two months to prepare a tribal proposal.[122] Indian agent George D. Day spoke on October 5, telling the assemblage that the commissioners were their friends, and they could either accept the Commission's offer, or be forced into allotment by the Dawes Act. Jerome pointed to Parker's wealth erroneously as an example of what allotment would bring to the average tribal member.[123] Parker had proposed that $500,000 be added to the $2,000,000 offer, and that Congress make the decision about it. Kiowa chief Tohauson spoke on October 6, saying that neither he nor many in his tribe would sign the agreement.[124] At the final Fort Sill meeting on October 11, the Commission pressed for signatures from reluctant Kiowas.[125]

Anadarko was the location for the October 14, 15, 17 sessions, which were noted for the Kiowa reluctance to sign the document.[126] On October 22 on Fort Sill, the Commission notified the President they had the required number of signatures for the Agreement with the Comanche, Kiowa and Apache (1892).[127][128]

Protests began immediately that there had been irregularity in obtaining signatures, and that individuals had been misled about the terms of the agreement.[127] Lone Wolf and Quanah Parker joined others many times in Washington D.C. meetings to air their viewpoints.[129] From 1893 each succeeding Congress attempted to amend the agreement before its final ratification in 1900.[130]

Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock

Once the Commission laid claim to a sufficient number of signatures for passage, Lone Wolf and other Kiowa alleged fraud. In October 1899, a petition of a majority of Kiowa males was presented to Congress questioning the validity of the agreement. Upon the onset of the allotment process, Lone Wolf filed a complaint with the Supreme Court in the District of Columbia, seeking an injunction against the Department of Interior. Former Congressman William Springer acted as the tribal attorney. The Indian Rights Association also became involved. The complaint alleged that the agreement was unconstitutional on the grounds that it conflicted with the Treaty of Medicine Lodge requirement of signatures of three-fourths of all tribal adult males.[131]

In the 1903 Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock decision, the Court ruled against Lone Wolf, stating that the Congress acted in good faith, and the judiciary branch of government should not question its motives. The Court ruled that Congress was within its plenary powers to abrogate treaties when it acts in the best interests of the tribes.[132]

Pawnee – November 23, 1892

The Pawnee had four bands:Chaui (Grand Pawnee), Kitkahahki (Republican Pawnee), Pitahawirata (Tapage Pawnee) and Skidi (Loups).[133] In 1876, the Pawnee ceded their reservation in Nebraska, sold by the United States government through a public sale. Proceeds of the sale of the Nebraska reservation were used to relocate the tribe to Indian Territory, on land purchased from the Cherokee. Surplus funds remaining after the purchase and relocation were to be credited to the Pawnee at the United States Treasury. The Pawnee owned 230,014 acres (930.83 km2; 359.397 sq mi) in the Outlet, and 53,006 acres (214.51 km2; 82.822 sq mi) south of there.[134][135]

In the August 1892 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent D.J.M. Wood, the total Pawnee reservation population was counted at 798, of which 382 were male and 416 were female. Of the total population, 400 were considered of mixed blood. The number under the age of 24 who were considered literate was reported at 160. And 225 of the Pawnee were reported as being able to use the English language. Of 283,020 acres (1,145.3 km2; 442.22 sq mi), 1,986 acres (8.04 km2; 3.103 sq mi) were under cultivation. The report contains a section on the Pawnee participation in the Ghost Dance, which promised to bring a new messiah to force intruders off their land, and return the buffalo. The named prophet on the reservation was Frank White, whom the agent had arrested. The agent refers to having avoided a Wounded Knee disaster.[136] The Ghost Dance religion took root among the Pawnee in 1891, after Frank White became a convert while participating in it with the Comanches and the Wichitas. By the date mentioned in the agent's report, two-thirds of the Pawnee had become participants. Many within the tribe had given up reservation labors in favor of serving the new messiah with the dancing. When the government objected, the Pawnee practiced their religion covertly. White's arrest was a government attempt to quash the religion.[137][138]

In attendance at the first October 31, 1892 Commission session were Jerome, Wilson and Helen P. Clarke, of the Piegan tribe, to facilitate the allotments. Harry Coons acted as monitor on behalf of the Pawnee. Jerome began the sessions by referring to the dictates of the Dawes Act. Jerome told the Pawnee they had no option but to capitulate, and that leasing to cattlemen was forbidden. The Pawnee were concerned about being deprived of their livelihood, and about future generations of Pawnee not being beneficiaries of the agreement. Jerome threatened them with cutting off food rations, and told them their only protection from white intruders on their land was to cede the land to the government.[139]

On November 2, Jerome presented the terms of the government's offer. Sticking points were the $1.25 per acre being proposed, and the stipulation that of the 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi) person, only 80 acres (0.32 km2; 0.13 sq mi) could be used for agriculture.[139] The Pawnee wanted the 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi) with no restrictions, and $2.50 per acre for ceded land. Sun Chief had heard that Quanah Parker had negotiated $1.50 per acre, but Jerome said the Comanches only received 80 cents per acre. After five days, on November 9 and 10, the Pawnee decided to lower their price to $1.50 an acre. Jerome refused. Sun Chief offered to split the difference between the government's offer and the Pawnee demand. Jerome refused. When the tribal representatives expressed dissatisfaction with the quality of government clothing allotments, Warren Sayre offered to give the tribe half of the clothing allowance in cash. Brave Chief wanted assurances that the government would support the tribe's right to conduct the Ghost Dances. Sayre confirmed it vocally but refused to put it in writing.[138]

Sun Chief announced that he had given his approval for the Commission agreement. On November 23, Agreement with the Pawnee (1892) was voted upon and signed. From the 283,020 acres (1,145.3 km2; 442.22 sq mi) that made up the Pawnee reservation, 111,932 acres (452.97 km2; 174.894 sq mi) were converted to individual allotments. 171,088 acres (692.37 km2; 267.325 sq mi) ceded as surplus ($1.25 per acre). $80,000 was to be paid in cash upon Congressional ratification of the agreement. The remainder would be held in the United States Treasury at 5% per annum, with annual per capita distributions. The allotments were to be selected by the individual tribal members within four months of Congressional ratification of the agreement. If any member failed to make the selection within that time frame, the selection would be made for them by the local agent. Land patents to the individual land allotted were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. Pawnee Ralph C. Weeks served as interpreter. Congress ratified the document on March 3, 1893.[140][141]

In 1950, the Indian Claims Commission ruled the Pawnee had been underpaid for sale of its Nebraska reservation, and awarded the tribe more than $7,000.000.[142]

Failure to negotiate treaties

Osage, Kaw and Otoe

In the August 1892 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, the Osage and Kaw report was submitted by Indian Agent L.J. Miles. The population on the Osage the reservation numbered 1,644. The Osage were described as being a religious people who were honest and having pride in their heritage. The Kaw on the reservation were counted at 209. The Kaw populace was described as a generous people who gave away their own possessions to others.[143] On June 22, 1893, the Commission attempted negotiation with the Osage, and the Kaw. Neither tribe was interested in negotiating. Section 8 of the Dawes act excluded the Osage, so they could not be compelled to accept allotments. The Osage had their own government with a written constitution. The Kaw refused to entertain the idea of allotments unless the Commission was able to secure an agreement with the Ponca.[144]

In the 1892 Indian Affairs report, the Otoe report was submitted by Indian Agent D.J.M. Wood, and the population was counted as 362, living on 129,113 acres (522.50 km2; 201.739 sq mi). Helen P. Clark had already made allotments to many Otoe. The Ghost Dance, which the agent refers to as "The Messiah Craze", was quashed by arresting one participant named Buffalo Black .[145] The Otoe refused to meet with the Commission.[146]

Ponca

Ponca Dakota Territory land was given to the Sioux in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. In 1877, the Ponca were forcibly removed to Indian Territory. President Rutherford B. Hayes denied the appeal to stop the removal, filed by Chiefs Standing Bear, Standing Buffalo, White Eagle and Big Chief.[147] The Ponca lived on 101,894 acres (412.35 km2; 159.209 sq mi) in the Outlet, purchased for $50,000 in 1878.[148] In the August 1892 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent D.J.M. Wood, the total Ponca reservation population was counted at 567. Two hundred of the Ponca were reported as being able to use the English language. Total tribal earnings during the previous year were reported as $325.71.[149]

During October 1891 and spring 1892, the Commission met with the Ponca. The commissioners read the Dawes Act. White Eagle suggested the white homesteaders "..stay on their own reservation." The Ponca felt there was no evidence that allotments, or lack thereof, made any difference in a tribe's standard of living. On April 12, Sayre presented the government's proposal. The Commission threatened that Congress could cut off Ponca annual appropriations.[150] A Ponca delegation visited the Cherokee Nation for advice, but the Cherokee were unable to help.[151]

In April 1893, negotiations resumed, during which Jerome threatened that the government can do anything it wants. On April 10, Jerome told the Ponca that they would stay until the Ponca agreed to allotments. Sayre threatened with possible cancellation of grass lease money. The Ponca held firm that they owned the land, and reminded the Commission of what happened to the Ponca's land in Dakota Territory. Jerome responded that the government would force the allotment on the Ponca, and threatened one attendee with jail. The Commission threatened to cut off all government services unless the Ponca capitulated. The Commission gave up on June 6, 1893, twenty months after they began.[152]

See also

Notes

- Johansen, Pritzker (2007) p. 278

- "Indian Appropriations Act 1889, Sec 14". Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- "Indian Appropriations Act 1889, Sec 15". Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- Hagan (2003) p. 235

- Hagan (2003) p. 13

- Chiorazzi, Michael; Most, Marguerite (2005). Prestatehood Legal Materials: A Fifty-State Research Guide, Including New York City and the District of Columbia. Taylor & Francis, Inc. p. 941. ISBN 978-0-7890-2056-7.

- Shearer, Benjamin F (2004). The Uniting States: Oklahoma to Wyoming. Greenwood. p. 977. ISBN 978-0-313-33107-7.

- "Organic Act for the Territory of Oklahoma". Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. University of Oklahoma Library. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- Brown, Kenny L. "Oklahoma Territory". Oklahoma Historical Society. Oklahoma State University Library. Archived from the original on 2011-11-14. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- Hagan (2003) p. 20

- Report of the Secretary of the Interior. United States government. 1891. p. 398.

- Hagan (2003) p. 182

- Hagan (2003) p. 223

- Hagan (2003) p. 19

- Hagan (2003) p. 38

- Hagan (2003) p. 37

- Hagan (2003) p. 42

- Hagan (2003) p. 18

- Owens, Ron (2004). Medal of Honor: Historical Facts and Figures. Turner Publishing Company. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-56311-995-8.

- Hagan (2003) p. 28

- Hagan (2003) p. 34

- May, Jon D. "Iowa". Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1890) p. 199

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1890) p. 200

- Hagan (2003) pp. 29–30

- Hagan (2003) pp. 44–48

- Deloria, DeMaille (1999) pp. 319–322

- "United States Court of Claims to the Iowa Tribe of Indians, Oklahoma". Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- "1867 Treaty with Sauk and Foxes". Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- Hagan (2003) p. 30

- Hagan (2003) pp. 51–52

- Deloria, DeMaille (1999) pp. 323–326

- Hagan (2003) p. 54

- "Treaty with the Potawatomi 1867". Kappler's Indian Affairs:Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Hagan (2003) p. 55

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1890) pp. 200–201

- Hagan (2003) p. 56

- Deloria, DeMaille (1999) pp. 326–329

- Hagan (2003) p. 57

- "Treaty with the Shawnee 1825". Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Smith, Pamela A. "Absentee Shawnee". Oklahoma Historical Society. Oklahoma State University Library. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Deloria, DeMaille (1999) pp. 329–331

- Hagan (2003) pp. 57–58

- Stewart, Omer C (1993). Peyote Religion: A History. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-8061-2457-5.

- "1861 Treaty of Little Arkansas". Kappler's Indian Affairs:Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- Brill, Charles J (1938). "Appendix C-Medicine Lodge Treaty". Custer, Black Kettle, and the Fight on the Washita. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 277–288. ISBN 978-0-8061-3416-1.

- Luebering, JE (2010). Native American History. Britannica Educational. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-61530-265-9.

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1890) pp. 177–178

- Mooney (1991), p. 764

- Mooney (1991), pp. 817–819

- Berthrong (1992) pp. 138–139

- Berthrong (1992) pp. 150–152

- Hagan (2003) p. 72

- Berthrong (1992) p. 164

- Hagan (2003) p. 76

- Berthrong (1992) pp. 164–165

- Berthrong (1992) p. 167

- Deloria, DeMaille (1999) pp. 331–334

- Berthrong (1992) pp. 148–149

- Hagan (2003) p. 69

- Hagan (2003) p. 79

- Hagan (2003) pp. 80–82

- Berthrong (1992) pp. 175–176

- "Treaty with the Choctaw and Chickasaw 1855". Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- Prucha, Francis Paul (1997). American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly. University of California Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-520-20895-7.

- "Treaty with the Choctaw and Chickasaw 1866". Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- Robert Goins, Charles Robert; Goble, Danney; Anderson, James H; Morris, John Wesley (2011). The Historical Atlas of Oklahoma. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8061-3483-3.

- Franks, Lambert (1997) p. 18

- May, Jon D. "Leased District". Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- Hagan (2003) p. 124

- Pool, Carolyn Garrett. "Wichita". Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1890) p. 187

- Hagan (2003) p. 125

- Hagan (2003) pp. 126–128

- Hagan (2003) p. 132

- Deloria, DeMaille (1999) pp. 340–342

- Hagan (2003) p. 133

- Nunley, M. Christopher. "Kickapoo". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- Latorre, Dolores L. and Felipe A (1991). Mexican Kickapoo Indians. Dover Publications. pp. 21–24. ISBN 978-0-486-26742-5.

- Hagan (2003) pp. 31–32

- Hagan (2003) pp. 58–60

- Hagan (2003) pp. 134–136

- Hagan (2003) p. 137

- Deloria, DeMaille (1999) pp. 343–346

- Hagan (2003) pp. 138–140

- Stott, Kelly McMichael (2002). Waxahachie: Where Cotton Reigned King. Arcadia Publishing SC. pp. 12, 13. ISBN 978-0-7385-2389-7.

- Carlisle, Jeffrey D. "Tonkawa Indians". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- May, Jon D. "Tonkawa". Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on 21 February 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1890) p. 194

- Deloria, DeMaille (1999) pp. 346–348

- Hagan (2003) p. 142

- "Treaty of New Echota". Kapper's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Archived from the original on 26 April 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- United States Soil Service (1938). Soil Survey. p. 4.

- The Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory: The Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole Nations. United States Census Office. 1894. p. 48.

- Conley, Robert J (2008). A Cherokee Encyclopedia. University of New Mexico. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-8263-3951-5.

- Hagan (2003) pp. 148, 157

- Rogers, Will (1996). The Papers of Will Rogers: Wild West and Vaudeville, April 1904 – September 1908. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2745-3.

- Hagan (2003) p. 23

- Hagan (2003) pp. 24–25

- Fitchett, Allen D. "Early History of Noble County". Chronicles of Oklahoma. Oklahoma State University Library. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- Louis F. Burns, Louis F. Burns (2004). A History of the Osage People. University of Alabama Press. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-8173-5018-5.

- Hagan (2003) p. 86

- Hagan (2003) pp. 96–98

- Hagan (2003) pp. 144–149

- Hagan (2003) pp. 150–154

- Hagan (2003) pp. 156–157

- Deloria, DeMaille (1999) pp. 348–351

- Hagan (2003) p. 158

- Hagan (2003) p. 160

- Hagan (2003) p. 162

- Hagan (2003) p. 165

- "1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty-Kiowa, Comanche". Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- Gwynne (2010) pp. 229–230

- Gwynne (2010) p. 286

- Gwynne (2010) p. 293

- Gwynne (2010) p. 298

- Gwynne (2010) p. 302

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1892) p. 386

- Hagan (2003) p. 183

- Gwynne (2010) pp. 308–309

- Hagan (2003) p. 189

- Hagan (2003) p. 192

- Hagan (2003) p. 193

- Hagan (2003) p. 195

- Hagan (2003) p. 197

- Hagan (2003) pp. 198–202

- Hagan (2003) p. 203

- Deloria, DeMaille (1999) pp. 355–358

- Gwynne (2010) p. 310

- Hagan (2003) p. 205

- Johnson, John W (2001). Historic US Court Cases. Routledge. pp. 689–702. ISBN 978-0-415-93756-6.

- Johansen, Pritzker (2007) pp. 569–572

- Jensen, Richard E (2010). The Pawnee Mission Letters, 1834–1851. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2987-7.

- Hagan (2003) p. 208

- "1876 Pawee relocation from Nebraska to Oklahoma". Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1892) p. 396

- Kerstetter, Todd M (2006). God's Country, Uncle Sam's Land: Faith and Conflict in the American West. University of Illinois Press. pp. 119, 120. ISBN 978-0-252-03038-3.

- Hagan (2003) pp. 212–217

- Hagan (2003) pp. 209–211

- Hagan (2003) p. 218

- Deloria, DeMaille (1999) pp. 361–363

- Hagan (2003) p. 219

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1892) pp. 390–391

- Hagan (2003) pp. 232–233

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1892) pp. 398–399

- Hagan (2003) p. 231

- Robinson, Charles M (2001). General Crook and the Western Frontier. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3358-4.

- "1878 Ponca Land Purchase-OK". Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1892) p. 393

- Hagan (2003) pp. 169–180

- Hagan (2003) p. 178

- Hagan (2003) pp. 223–230

References

- Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior. United States Government. 1890.

- Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior. United States Government. 1892.

- Berthrong, Donald J (1992). The Cheyenne and Arapaho Ordeal Reservation and Agency Life in the Indian Territory, 1875–1907. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2416-2.

- Deloria Jr., Vine J; DeMaille, Raymond J (1999). Documents of American Indian Diplomacy Treaties, Agreements, and Conventions, 1775–1979. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3118-4.

- Franks, Kenny Arthur; Lambert, Paul F (1997). Oklahoma: The Land and Its People. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-9944-3.

- Gwynne, S.C. (2010). Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History. Scribner. ISBN 978-1-4165-9105-4.

- Hagan, William T. (2003). Taking Indian Lands: The Cherokee (Jerome) Commission, 1889–1893. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3513-7.

- Johansen, Bruce Elliott; Pritzker, Barry (2007). Encyclopedia of American Indian History. ABC-CLIO, Incorporated. p. 278. ISBN 978-1-85109-817-0.

- Mooney, James (1991). The Ghost-Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890 (Bison Book ed.). London, NE: University of Nebraska Press – via Questia (subscription required) . ISBN 978-0-8032-8177-6.