Edmund Kirby Smith

Edmund Kirby Smith (May 16, 1824 – March 28, 1893) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the Mexican–American War. He later joined the Confederate States Army in the Civil War, and was promoted to general in the first months of the war. He was notable for his command of the Trans-Mississippi Department after the fall of Vicksburg to the United States

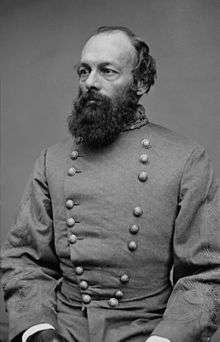

Edmund Kirby Smith | |

|---|---|

Smith in uniform, ca. 1861 | |

| Nickname(s) | "Ted", "Seminole" |

| Born | May 16, 1824 St. Augustine, Florida |

| Died | March 28, 1893 (aged 68) Sewanee, Tennessee |

| Place of burial | University Cemetery, Sewanee, Tennessee |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1845–1861 (USA) 1861–1865 (CSA) |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Third Corps, Army of Tennessee Trans-Mississippi Department |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War American Civil War |

| Signature | |

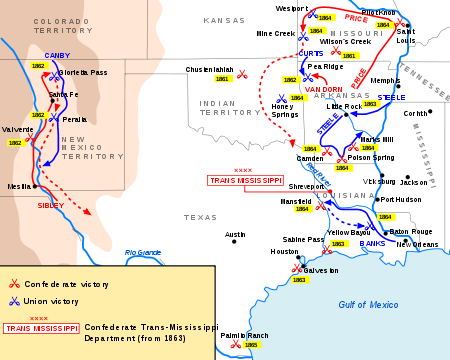

Smith was wounded at First Bull Run and distinguished himself during the Heartland Offensive, the Confederacy's unsuccessful attempt to capture Kentucky in 1862. He was appointed as commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department in January 1863. The area included most actions east of the Rocky Mountains and west of the Mississippi River. In 1863, Smith dispatched troops in an unsuccessful attempt to relieve the Siege of Vicksburg. After Vicksburg was captured by the Union in July, the isolated Trans-Mississippi zone was cut off from the rest of the Confederacy, and became virtually an independent nation, nicknamed 'Kirby Smithdom'. In the Red River Campaign of Spring 1864, he commanded victorious Confederate troops under General Richard Taylor, who defeated a combined Union army/navy assault under Nathaniel P. Banks.

On June 2, 1865, Smith surrendered his army at Galveston, Texas, the last general with a major field force. He quickly escaped to Mexico and then to Cuba to avoid arrest for treason. His wife negotiated his return during the period when the federal government offered amnesty to those who would take an oath of loyalty. After the war, Smith worked in the telegraph and railway industries. He also served as a college professor of mathematics at the University of the South in Tennessee. He botanized plant specimens and bequeathed his collection to the University of Florida.[1][2][3]

Early life

Edmund Kirby Smith was born in 1824 in St. Augustine, Florida, as the youngest child of Joseph Lee Smith, an attorney, and Frances Kirby Smith. Both his parents were natives of Litchfield, Connecticut, where their older children were born. The family moved to Florida in 1821, as the senior Smith was appointed as a Superior Court judge in the new Florida Territory, acquired by the U.S. from Spain.[4][5] Older siblings included Ephraim, born in 1807; and sisters Frances, born in 1809,[4] and Josephine, who died in 1835, likely of tuberculosis.[6][7] He was interested in botany and nature,[8] but in 1836, Smith's parents sent their second son to a military boarding school in Virginia,[9] and strongly encouraged a military career. He later enrolled in the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York.

In 1837, his sister Frances married Lucien Bonaparte Webster, a West Point graduate from Vermont and career Army artillery officer, whom she met when he was stationed at Fort Marion in St. Augustine. His commanding officer at the fort was the young Smiths' uncle. Webster later served in the Mexican–American War and died of yellow fever in 1853, when stationed on the Texas frontier at Fort Brown.[10]

Military education and career

On July 1, 1841, Kirby Smith entered West Point and graduated four years later in 1845, ranking 25th out of 41 cadets.[8] While there he was nicknamed "Seminole", after the Seminole people of Florida who had successfully resisted removal by the US. He was commissioned as a brevet second lieutenant in the 5th U.S. Infantry on July 1, 1845. Smith was promoted to second lieutenant on August 22, 1846, now serving in the 7th U.S. Infantry.[11]

In the Mexican–American War, Smith served under General Zachary Taylor at the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Resaca de la Palma.[5] He served under General Winfield Scott later, and received brevet promotions to first lieutenant for Cerro Gordo and to captain for Contreras and Churubusco. His older brother, Ephraim Kirby Smith (1807–1847), who graduated from West Point in 1826 and was a captain in the regular army, served with him in the 5th U.S. Infantry in the campaigns with both Taylor and Scott. Ephraim died in 1847 from wounds suffered at the Battle of Molino del Rey.[9]

After that war, Kirby Smith served as a captain (from 1855) in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, primarily in Texas. (From that year on through the war, Smith was accompanied by the youth Alexander Darnes, then 15, a mixed-race slave owned by his family, who served as his valet until emancipation and who may have been his half-brother.) [12][13]

Kirby Smith also taught at West Point after the war. He collected and studied materials as a botanist; like many other military officers, he was also a scientist. He donated to the Smithsonian Institution some of his collection and reports from his time at West Point.[14] Smith continued his botanical studies as an avocation for the remainder of his life. He is credited with collecting and describing several species of plants native to Tennessee and Florida.[15]

Kirby Smith was assigned to teaching mathematics at West Point, from 1849 to 1852. According to his letters to his mother, he was happy with this environment.[16]

Returning to troop-leading assignments, Smith served in the Southwest. On May 13, 1859, he was wounded in his thigh while fighting Comanche in the Nescutunga Valley of Kansas. also known as the Battle of Crooked Creek (Kansas).[5] When Texas seceded from the Union in 1861, Smith, promoted to major on January 31, 1861, refused to surrender his command at Camp Colorado in what is now Coleman, Texas, to the Texas State forces under Col. Benjamin McCulloch; he expressed his willingness to fight to hold it.[9] On April 6, he resigned his commission in the U.S. Army to join the Confederacy.[11]

American Civil War

On March 16, 1861, Smith entered the Confederate forces as a major in the regular artillery; that day he was transferred to the regular cavalry with the rank of lieutenant colonel.[11] After serving briefly as Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's assistant adjutant general in the Shenandoah Valley,[17] Smith was promoted to brigadier general on June 17, 1861. He was given command of a brigade in the Army of the Shenandoah, which he led at the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21.[18] Wounded severely in the neck and shoulder, he recuperated while commanding the Department of Middle and East Florida. He returned to duty on October 11 as a major general and division commander in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.[19]

In February 1862, Smith was sent west to command the eastern division of the Army of Tennessee. Cooperating with Gen. Braxton Bragg in the invasion of Kentucky, he scored a victory at the Battle of Richmond, Kentucky on August 30, 1862, but did not link up with Bragg's army until after the Battle of Perryville. On October 9, he was promoted to the newly created grade of lieutenant general, becoming a corps commander in Bragg's Army of Tennessee.[19] Smith received the Confederate "Thanks of Congress" on February 17, 1864, for his actions at Richmond.[lower-alpha 1]

Trans-Mississippi Department

On January 14, 1863, Smith was transferred to command the Trans-Mississippi Department (primarily Arkansas, Western Louisiana, and Texas) and he remained west of the Mississippi River for the balance of the war, based part of this time in Shreveport, Louisiana. As forces under Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant tightened their grip on the river, Smith attempted to intervene. However, his department never had more than 30,000 men stationed over an immense area and he was not able to concentrate forces adequately to challenge Grant nor the Union Navy on the river.[19]

Following the Union capture of the remaining strongholds at Vicksburg and Port Hudson and their closing of the Mississippi to the enemy, Smith was virtually cut off from the Confederate capital at Richmond. He had to command a nearly independent area of the Confederacy, with all of the inherent administrative problems. The area became known in the Confederacy as "Kirby Smithdom".[20] He was thought of as a virtual military dictator, and negotiated directly with foreign countries.[21]

In the spring of 1864, Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, directly under Smith's command, soundly defeated Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks at the Battle of Mansfield in the Red River Campaign on April 8, 1864.[22] After the Battle of Pleasant Hill on April 9, Smith joined Taylor and dispatched half of Taylor's army, Walker's Greyhounds, under the command of Maj. Gen. John George Walker, northward to defeat Union Maj. Gen. Frederick Steele's incursion into Arkansas. This decision, strongly opposed by Taylor, caused great enmity between the two men.[23]

With the pressure relieved to the north, Smith attempted to send reinforcements east of the Mississippi. But, as in the case of his earlier attempts to relieve Vicksburg, it proved impossible due to Union naval control of the river. Instead he dispatched Maj. Gen. Sterling Price, with all available cavalry, on an unsuccessful invasion of Missouri. Thereafter he conducted the war west of the river principally through small raids and guerrilla activity.[24]

By now a full general (as of February 19, 1864, one of seven generals in the Confederate Army),[19] Smith negotiated the surrender of his department on May 26, 1865. While Brigadier General Stand Watie and the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles regiment did not surrender until 23 June 1865, Kirby was the last full general to do so and signed the terms of surrender in Galveston, Texas, on June 2, nearly 8 weeks after Robert E. Lee's surrender.[5] He immediately left the country for Mexico and then to Cuba, to escape potential prosecution for treason.[25] In August that year, General Beauregard's house near New Orleans was surrounded by Federal troops who suspected the general of harboring Smith. All the inhabitants were locked in a cotton press overnight. Beauregard complained to General Sheridan, who expressed his annoyance at the treatment of the high-ranking officer, his erstwhile enemy.[26] Smith returned to the United States later that year to take an oath of amnesty at Lynchburg, Virginia, on November 14, 1865.[11]

Personal life

In August 1861, Kirby Smith met Cassie Selden (1836–1905), the daughter of Samuel S. Selden of Lynchburg. While recovering from being wounded at the First Battle of Manassas, he still found time for wooing. The couple married on September 24. Cassie wrote on October 10, 1862 from Lynchburg, asking what to name their first child. She suggested "something uncommon as I consider her an uncommon baby." The new baby was later named Caroline.[27]

The couple briefly reunited when Cassie followed her husband to Shreveport in February 1863. In the spring of 1864, she moved to Hempstead, Texas, where she remained for the duration of the war. After the war's end, Cassie traveled to Washington to negotiate for her husband's return to the United States from Cuba where he had fled.[28]

In 1875 Kirby Smith accepted an appointment as a professor at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. There the family lived happily until the end of his life. They had five sons and six daughters: Caroline (1862–1941), Frances (1864–1930), Edmund (1866–1938), Lydia (1868–1962), Nina (1870–1965), Elizabeth (1872–1937), Reynold (1874–1962), William (1876–1967), Josephine (1878–1961), Joseph Lee (1882–1939), and Ephraim (1884–1938).

Reynold, William, Joseph, and Ephraim all played for the Sewanee Tigers football team. Joseph and Ephraim both achieved All-Southern status in football. Joseph was a member of the famed 1899 "Iron Men" and Ephraim was selected for Sewanee's All-Time football team.[29]

Later life

After the war, Kirby Smith was active in the telegraph business and in higher education. From 1866 to 1868, he was president of the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Company. When that effort ended in failure, he started a preparatory school in New Castle, Kentucky, which he directed until it burned in 1870.[9] In 1870, he combined efforts with former Confederate General Bushrod Johnson.[30] He served as the chancellor of the University of Nashville from 1870 to 1875.[31]

In 1875, Kirby Smith left that post to become professor of mathematics and botany at the University of the South at Sewanee, Tennessee.[8] Part of his collection from those years was donated to the universities of North Carolina and Harvard, and to the Smithsonian Institution. He kept up a correspondence with botanists at other institutions. He taught at the University of the South until he died of pneumonia in 1893. He was the last surviving full general from the Civil War. He is buried in the University Cemetery at Sewanee.[9]

Legacy

- His papers have been collected at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, in Edmund Kirby-Smith Papers, 1776–1906 (bulk 1840–1866).[7]

- A dormitory building on the campus of LSU in Baton Rouge is named Edmund Kirby Smith Hall.

- A portrait of Edmund Kirby Smith by Cornelius Hankins hangs in the Wyatt Center at Vanderbilt University.[31]

- In 1922, the state of Florida erected a statue honoring General Smith as one of Florida's two statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.[32][33] (The other is of Dr. John Gorrie, inventor of mechanical refrigeration and air conditioning.) On March 19, 2018, Florida Governor Rick Scott signed legislation to replace the statue with one of African-American civil rights activist and educator Mary McLeod Bethune.[34] The statue was to be moved to the Lake County Historical Museum in Tavares, after residents of his birthplace, St. Augustine, expressed no interest.[35] While Smith never lived in Lake County, when he was born it was a part of St. Johns County, whose seat is St. Augustine. At a County Commission meeting on July 24, 2018, about 24 residents spoke against, and none in favor, of bringing the statue to Lake County. Chairman Sullivan assured the crowd that the commission would tell the Historical Museum "that there is no longer a want or desire to bring this statue to Lake County".[36] Despite the strong opposition from the public and 9 mayors in the county, the Board of County Commissioners voted on August 6, 2019 to approve the statue installation.[37] Hundreds protested the transfer of the statue to Lake County on August 10, 2019, and citizen groups posted an online petition voicing opposition to the project, whose local sponsor was the Sons of Confederate Veterans.[38] On July 7, 2020, Lake County commissioners voted 4–1 against accepting the statue.[39]

- At the University of the South, in Sewanee, Tennessee, where he taught, he is commemorated by the Kirby-Smith Memorial on University Avenue, by Kirby-Smith Point.

- The Kirby-Smith Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy at Sewanee, and the Kirby-Smith Camp 1209, Sons of Confederate Veterans, in Jacksonville, Florida, are named for him.

- Kirby Smith Middle School in Jacksonville was named for him.

- During World War II the 422-foot (129 m) liberty ship SS E. Kirby Smith was built in Panama City, Florida, in 1943 and named in his honor.[40]

- In 2004, a life-sized statue of Kirby Smith and Alexander Darnes in an imaginary meeting (see below) was made by Maria Kirby Smith, a great-granddaughter of Smith.[8] It is installed in the courtyard of the Segui-Kirby Smith House, now owned by the St. Augustine Historical Society. This is the first public sculpture in the city to commemorate an African-American man.[12] Kirby-Smith said that she suspected Darnes was related to Smith as a half-brother or nephew, as her detailed work on the statues made her aware of the two men's close physical resemblance.[13]

Notes

- "... for the signal victory achieved by him in the battle of Richmond, Kentucky, on the thirtieth of August, and to all officers and soldiers of his command engaged in that battle" (Eicher 2001, p. 494).

- Carol Ann McCormick. Stars and Bars ... and Botany: E. Kirby Smith, UNC Herbarium Report, August 2011

- Chester, Edward W. Guide to the vascular plants of Tennessee. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2015, p. 72. ISBN 9781621901006

- General Kirby Smith Collection, Florida Museum of Natural History

- Webster & Webster 2000, p. .

- Chisholm 1911, p. 260.

- Webster & Webster 2000, p. 14.

- Edmund Kirby-Smith Papers, 1776–1906 (bulk 1840–1866), The Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, accessed November 25, 2013

- Matthew White, "Science, Race and Reunion: The Memorialization of Edmund Kirby Smith and His Slave Alexander Darnes", 2011 Phi Alpha Theta Biennial Conference, Orlando, Florida; Academia website

- Nofi 1995, pp. 347–48.

- [Frances Marvin Smith Webster and Lucien Bonaparte Webster, The Websters: Letters of an American Army Family in Peace and War, 1836–1853], ed. by Van R. Baker, Kent State University, 2000

- Eicher 2001, pp. 493–94.

- "Alexander Darnes and Kirby Smith Share Rare History" Archived September 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Jacksonville Historical Society

- Call, James (June 5, 2016). "What if Gen. Kirby Smith's statue was replaced by one of his former slave, Alex Darnes, M.D.?". Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- Julie B. Maglio, "Sculpture of Confederate General to be removed from Statuary Hall in D.C.", Hernando Sun, May 31, 2016

- Small, John K. "Studies in the Botany of the Southeastern United States.-Ix. I. The Sessile-Flowered Trillia of the Southern States." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 24, no. 4 (1897): 169–178

- "Letter from Edmund K. Smith to Frances K. Smith, February 14, 1849", Edmund Kirby-Smith Papers, Record Group #404 Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina

- Lossing 1881, p. 1306.

- Wagner, Gallagher & Finkelman 2002, p. 422.

- Cunningham 1992, p. 166.

- Davis 1999, p. 94.

- Monaghan, Jay (April 1974). "Review of Robert L. Kerby, Kirby Smith's Confederacy : the Trans-Mississippi South, 1863-1865". American Historical Review. 79 (2): 588–589. JSTOR 1850453.

- Maritime Activity Reports 1942, pp. 101–2.

- Sheehan-Dean 2007, pp. 145–47.

- Mechem & Malin 1964, p. 281.

- Townsend 2006, pp. 136–37.

- "AMERICA: ARRIVAL OF 'THE CUBA' ", The Manchester Guardian, September 4, 1865

- Jones 1955, pp. 177–79.

- "Mrs. Cassie Kirby-Smith". Confederate Veteran. 15: 563. 1907 – via archive.org.

- "Sewanee's All-Time Football Team". Sewanee Alumni News. February 1949.

- Morris, Roy Jr. (March 29, 2017). "Bushrod Johnson: Yankee Quaker, Confederate General". Warfare History Network. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- "Vanderbilt Collection – Peabody Campus – Wyatt Center: Edmund Kirby Smith". Tennessee Portrait Project. National Society of Colonial Dames of America in Tennessee. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- "Edmund Kirby Smith". Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- "Florida House panel OKs bill to remove Confederate statue". Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- Sexton, Christine; Saunders, Jim (March 21, 2018). "Florida to replace Confederate statue at US Capitol with civil-rights leader". Palm Beach Post.

- Commentary: Statue of Confederate general is no 'piece of art,' has no place in Lake County museum Retrieved July 2, 2018

- McNiff, Tim (July 24, 2018). "Lake County Commission does about-face on confederate statue". Daily Commercial.

- Ritchie, Lauren (August 5, 2019). "Lake County Commission Chairwoman Leslie Campione responsible for racial divide". Orlando Sentinel.

- https://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/breaking-news/os-ne-lake-county-statue-protest-20190810-t3mufcdejnclnh5722q6yg3jpe-story.html

- "Lake County asks Gov. DeSantis to move statue of Confederate out of their community". WOFL (FOX 35 Orlando). July 7, 2020.

- Maritime Activity Reports 1942, p. 135.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 25 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 260CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cunningham, Sumner A.; Sons of Confederate Veterans (Organization); Confederated Southern Memorial Association (U.S.); United Confederate Veterans; United Daughters of the Confederacy (1922), Confederate Veteran, S.A. Cunningham

- Davis, William C. (1999), The American Frontier: Pioneers, Settlers, & Cowboys, 1800–1899, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 978-0-8061-3129-0

- Eicher, John H.; Eicher, David J. (2001), Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1

- Jones, Katharine M. (1955), Heroines of Dixie, New York: Konecky & Konecky

- Lossing, Benson John (1881), Harpers' Popular Cyclopaedia of United States History from the Aboriginal Period to 1876, New York: Harper, OCLC 1446520

- Maritime Activity Reports (1942), Marine News, 29

- Mechem, Kirke; Malin, James Claude (1964), The Kansas Historical Quarterly, Kansas State Historical Society Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Nofi, Albert A. (1995), A Civil War Treasury: Being a Miscellany of Arms and Artillery, Facts and Figures, Legends and Lore, Muses and Minstrels, Personalities and People, New York: Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-0-306-80622-3.

- Sheehan-Dean, Aaron (2007), Struggle for a Vast Future: The American Civil War, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84603-213-4

- Townsend, Stephen A. (2006), The Yankee Invasion of Texas, College Station: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 978-1-58544-487-8

- Wagner, Margaret E.; Gallagher, Gary W.; Finkelman, Paul (2002), The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0-684-86350-4

- Webster, Frances Marvin Smith; Webster, Lucien Bonaparte (2000), Baker, Van R. (ed.), The Websters: Letters of an American Army Family in Peace and War, 1836-1853, Kent State University Press, ISBN 9780873386548

Further reading

- Forsyth, Michael J. (2003), The Camden Expedition of 1864 and the Opportunity Lost by the Confederacy to Change the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., ISBN 978-0-7864-1554-0.

- Kerby, Robert L (1991). Kirby Smith's Confederacy : the Trans-Mississippi South, 1863-1865. Reprint of 1972 edition. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0817305467.

- Parks, Joseph Howard (1954), General Edmund Kirby Smith, CSA. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, ISBN 978-0-8071-1800-9.

- Pollard, Edward Alfred (1867), Lee and His Lieutenants: Comprising the Early Life, Public Services, and Campaigns of General Robert E. Lee and His Companions in Arms, with a Record of Their Campaigns and Heroic Deeds. New York: E.B. Treat & Co, OCLC 1487259.

- Prushankin, Jeffery S. (2005), A Crisis in Confederate Command: Edmund Kirby Smith, Richard Taylor and the Army of the Trans-Mississippi. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, ISBN 978-0-8071-3088-9.

- Smith, Ephraim Kirby (2006), To Mexico with Scott: Letters of Captain E. Kirby Smith to His Wife, edited and with Introduction by R.M. Johnston, scanned and reissued.

- Sifakis, Stewart (1988), Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts on File, ISBN 978-0-8160-2202-1.

- Silkenat, David. Raising the White Flag: How Surrender Defined the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019. ISBN 978-1-4696-4972-6.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

External links

- Edmund Kirby Smith at Find a Grave

- Edmund Kirby-Smith Papers, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Architect of the Capitol description and photo of Smith's statue

- Kirby-Smith Middle School website in Jacksonville, Florida

- Memorials at Sewanee