Chickasaw Nation

The Chickasaw Nation is a federally recognized Native American nation, located in Oklahoma in the United States. The Chickasaw Nation originated in its homeland of the American Southeast, with territory in what is defined as modern-day Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama and Kentucky.

Flag | |

Seal of the Chickasaw Nation Seal | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 66,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Chickasaw language | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional tribal religion, Protestantism (Baptist, Methodist)[2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Choctaw |

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European Americans knew the Chickasaw as one of the historic Five Civilized Tribes, all of whom were based in what became the Southeastern United States.

History

Hernando de Soto is credited as being the first European to contact the Chickasaw, during his travels of 1540. He discovered them to have an agrarian society with a sophisticated governmental system, complete with their own laws and religion. They lived in towns.[3]

During the colonial period, some Chickasaw towns traded with French colonists from La Louisiane, including their settlements at Biloxi, or Mobile. They were also reached by Scots or English traders coming west from Georgia or the Carolinas.

After the American Revolutionary War, the new state of Georgia was trying to strengthen its claim to western lands, which it said went to the Mississippi River under its colonial charter. It also wanted to satisfy a great demand by planters for land to develop, and the state government, including the governor, made deals to favor political insiders. Various development companies formed to speculate in land sales. After a scandal in the late 1780s, another developed in the 1790s. In what was referred to as the Yazoo land scandal of January 1795, the state of Georgia sold 22 million acres of its western lands to four land companies, although this territory was occupied by the Chickasaw and other tribes, and there were other European nations with some sovereignty in the area.[4] This was the second Yazoo land sale, which generated outrage when the details were publicized. Reformers passed a state law forcing the annulment of this sale in February 1796.[5] But the Georgia-Mississippi Company had already sold part of its holdings to the New England Mississippi Company, and it had sold portions to settlers. Conflicts arose as settlers tried to claim and develop these lands. Georgia finally ceded its claim to the US in 1810, but the issues took nearly another decade to resolve.

Abraham Bishop of New Haven, Connecticut, wrote a 1797 pamphlet to address the land speculation initiated by the Georgia-Mississippi Company. Within this discussion, he wrote about the Chickasaw and their territory in what became Mississippi:

The Chickasaws are a nation of Indians who inhabit the country on the east side of the Mississippi, on the head branches of the Tombeckbe (sic), Mobille (sic) and Yazoo rivers. Their country is an extensive plain, tolerably well watered from springs, and a pretty good soil. They have seven towns, and their number of fighting men is estimated at 575.[6]

The Chickasaw sold a section of their lands with the Treaty of Tuscaloosa, resulting in the loss of what became known as the Jackson Purchase, in 1818. This area included western Kentucky and western Tennessee, both areas not heavily populated by members of the tribe. They remained in their primary homeland of northern Mississippi and northwest Alabama until the 1830s. After decades of increasing pressure by federal and state governments to cede their land, as European Americans were eager to move into their territory and had already begun to do so as squatters or under fraudulent land sales, the Chickasaw finally agreed to cede their remaining Mississippi Homeland to the U.S. under the Treaty of Pontotoc Creek and relocate west of the Mississippi River to Indian Territory.

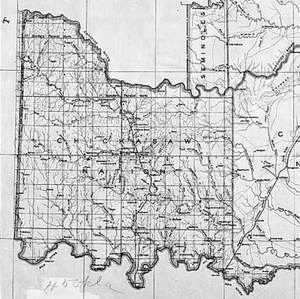

During Indian Removal of the 1830s, the Chickasaw and Choctaw signed the Treaty of Doaksville, by which the Chickasaw purchased the western lands of the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory. Their area in the western area of the nation was called the Chickasaw District. It consisted of what are now Panola, Wichita, Caddo, and Perry counties.

Although originally the western boundary of the Choctaw Nation extended to the 100th meridian, virtually no Chickasaw lived west of the Cross Timbers, due to continual raiding by the Plains Indians of the southern region. The United States eventually leased the area between the 100th and 98th meridians for the use of the Plains tribes. The area was referred to as the "Leased District".[7]

The division of the Choctaw Nation was ratified by the Choctaw–Chickasaw Treaty of 1854. The Chickasaw constitution, establishing the nation as separate from the Choctaw, was signed August 30, 1856, in their new capital of Tishomingo (now Tishomingo, Oklahoma). The first Chickasaw governor was Cyrus Harris. The nation consisted of four divisions; Tishomingo County, Pontotoc County, Pickens County, and Panola County. Law enforcement in the nation was provided by the Chickasaw Lighthorsemen. Non-Indians fell under the jurisdiction of the Federal court at Fort Smith.

Following the Civil War, the United States forced the Chickasaw Nation into a new peace treaty due to their support for the Confederacy. Under the new treaty, the Chickasaw (and Choctaw) ceded the "Leased District" to the United States.

20th century to present

The role of tribal governments in Indian Territory came to an end in 1907 when Oklahoma entered the union as the 46th state. As a result, Chickasaws were granted United States citizenship. From that point until 1971, the president of the United States appointed the representative of the Chickasaw Nation. Douglas H. Johnston was the first man to serve in this capacity. Governor Johnston served the Chickasaw Nation from 1906 until his death in 1939 at age 83.

During the 1960s and the period of the civil rights movement, Native American Indian activism was also on the rise. A group of Chickasaw met at Seeley Chapel, a small country church near Connerville, Oklahoma, to work toward the reestablishment of its government. With the passage of Public Law 91-495, their tribal government was recognized by the United States.

In 1971, the people held their first tribal election since 1904. They elected Overton James by a landslide as governor of the Chickasaw Nation.

Since the 1980s, tribal government has focused on building an economically diverse base to generate funds that will support programs and services to Indian people.

Government and politics

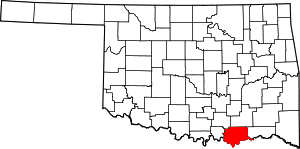

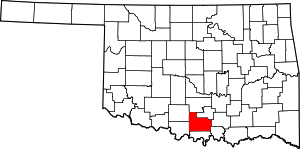

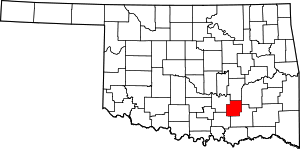

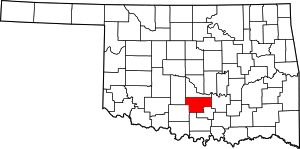

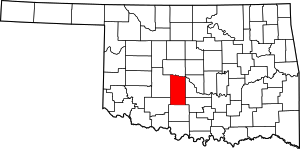

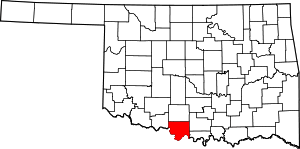

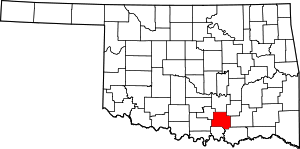

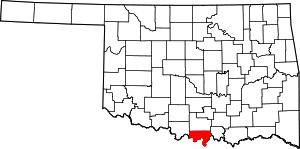

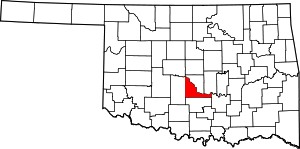

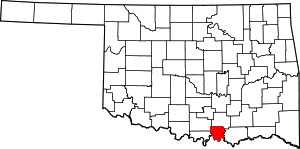

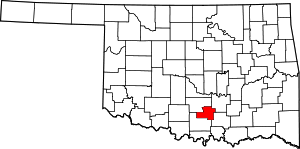

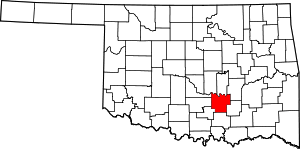

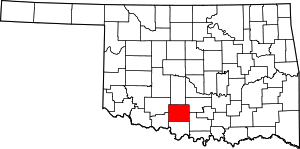

The Chickasaw Nation is headquartered in Ada, Oklahoma. Their tribal jurisdictional area is in Bryan, Carter, Coal, Garvin, Grady, Jefferson, Johnston, Love, McClain, Marshall, Murray, Pontotoc, and Stephens counties in Oklahoma. The tribal governor is Bill Anoatubby.[1]

The Chickasaw Nation’s current three-department system of government was established with the ratification of the 1983 Chickasaw Nation Constitution. The elected officials provided for in the Constitution believe in a unified commitment, whereby government policy serves the common good of all Chickasaw citizens. This common good extends to future generations as well as today’s citizens.

The structure of the current government encourages and supports infrastructure for strong business ventures and an advanced tribal economy. The use of new technologies and dynamic business strategies in a global market are also encouraged.

Monies generated in business are divided between investments for further diversification of enterprises and support of tribal government operations, programs and services for Indian people. This unique system is key to the Chickasaw Nation’s efforts to pursue self-sufficiency and self-determination, which helps ensure that Chickasaws stay a united and thriving people.

Revenues generated by Chickasaw Nation tribal business endeavors fund more than 200 programs and services. These programs cover education, health care, youth, aging, housing and more, all of which directly benefit Chickasaw families, Oklahomans and their communities.

Governor Bill Anoatubby appointed Charles W. Blackwell as the Chickasaw Nation's first Ambassador to the United States in 1995.[8] (Blackwell had previously served as the Chickasaw delegate to the United States from 1990 to 1995).[8] At the time of his appointment in 1995, Blackwell became the first Native American tribal ambassador to the United States government.[8] Blackwell served in Washington as ambassador from 1995 until his death on January 3, 2013.[8] Governor Bill Anoatubby named Neal McCaleb ambassador-at-large in 2013, a role similar to that of the late Charles Blackwell.

Economy

The Chickasaw Nation operates more than 100 diversified businesses in a variety of services and industries, including manufacturing, energy, health care, media, technology, hospitality, retail and tourism. Among these are Bedré Fine Chocolate in Davis, Lazer Zone Family Fun Center and the McSwain Theatre in Ada; The Artesian Hotel in Sulphur; Chickasaw Nation Industries in Norman, Oklahoma; Global Gaming Solutions, LLC; KADA (AM), KADA-FM, KCNP, KTLS, KXFC, and KYKC radio stations in Ada; and Treasure Valley Inn and Suites in Davis. In 2002, the Chickasaw Nation purchased Bank2 with headquarters in Oklahoma City. It was renamed Chickasaw Community Bank in January of 2020. It started with $7.5 million in assets and has grown to $135 million in assets today.[9] Chickasaw Community Bank

The estimated annual tribal economic impact in the region from all sources is more than $3.18 billion.[1] In addition, the Chickasaw Nation operates historical sites and museums, including the Chickasaw Cultural Center, Chickasaw Nation Capitols, and Kullihoma Grounds.

Their casinos include Ada Gaming Center, Artesian Casino, Black Gold Casino, Border Casino, Chisholm Trail Casino, Gold Mountain Casino, Goldsby Gaming Center, Jet Stream Casino, Madill Gaming Center, Newcastle Casino, Newcastle Travel Gaming, RiverStar Casino, Riverwind Casino, Treasure Valley Casino, Texoma Casino, SaltCreek Casino, Washita Casino and WinStar World Casino. They also own Lone Star Park in Grand Prairie, Texas and Remington Park Casino in Oklahoma City.

Notable people

- Bill Anoatubby, Governor of the Chickasaw Nation since 1987

- Jodi Byrd, Literary and political theorist

- Jack Brisco and Gerry Brisco, pro-wrestling tag team

- Jeff Carpenter, Recording artist and co-founder of the Native American music group Injunuity

- Edwin Carewe (1883–1940), movie actor and director[10]

- Charles David Carter, Democratic U. S. Congressman from Oklahoma[11]

- Travis Childers, U.S. Congressman from Mississippi

- Helen Cole (1922-2004), politician from Oklahoma, served in both the state house of Representatives and the state Senate, in addition to mayor of Moore, Oklahoma. One of her sons, Tom Cole, is a member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

- Tom Cole, Republican US Congressman from Oklahoma

- Hiawatha Estes, architect

- Cyrus Harris, first Governor of the Chickasaw nation

- John Herrington, astronaut, first enrolled Native American to travel in space

- Linda Hogan, author, writer-in-residence of the Chickasaw Nation

- Overton James, Governor of the Chickasaw Nation (1963-1987)

- Douglas H. Johnston, Governor of Chickasaw Nation (1898-1902 and 1904-1939)

- Neal McCaleb, civil engineer and politician

- Bryce Petty, quarterback for the Miami Dolphins

- Eula Pearl Carter Scott, pilot, later elected to the Chickasaw legislature, where she served three terms[12][13]

- Jerod Impichchaachaaha' Tate, composer and pianist

- Rebecca Sandefur, sociologist and winner of a MacArthur "Genius" Fellowship

- Te Ata Fisher storyteller and actress[14]

- Fred Waite (1853 - 1895), politician representative, senator, Speaker of the House and Attorney General of Chickasaw Nation

- Estelle Chisholm Ward, first woman to represent tribal interests in Washington, D.C.

- Kevin K. Washburn, attorney, federal government official and law professor

Notes

- 2011 Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory. Archived April 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. 2011: 8. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- Pritzker, 373

- "Official Site of the Chickasaw. Retrieved December 26, 2012". Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- Lamplugh, George R. (2010). "James Gunn: Georgia Federalist, 1789-1801". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 94 (3): 313.

- George R. Lamplugh (1986). Politics on the Periphery: Factions and Parties in Georgia, 1783-1806. University of Delaware Press. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-0-87413-288-5.

- Bishop, Abraham (1797), Georgia Speculation Unveiled; In Two Numbers, New Haven: Elisha Babcock, p. 42

- Arrell Morgan Gibson (1981). "The Federal Government in Oklahoma". Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-8061-1758-3.

- "Chickasaw Nation Ambassador Charles W. Blackwell – a Man of Vision". KXII. January 4, 2013. Archived from the original on January 8, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- "Native American Data for Jay J Fox". RootsWeb. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- "Carter, Charles David (1868–1929)." Archived November 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "Chickasaw Nation Hall of Fame - Eula Pearl Carter Scott". Hof.chickasaw.net. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- oklahoma state senate staff. "Oklahoma State Senate - News". Oksenate.gov. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- "TE ATA (1895-1995)". Archived from the original on November 24, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

Chickasaw Community Bank https://www.ccb.bank/about-us/who-we-are

References

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

Further reading

- Johnson, Neil R.; C. Neil Kingsley (editor). The Chickasaw Rancher. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2001 (Revision of 1960 edition). ISBN 978-0-87081-635-2

- Kappler, Charles (ed.). "TREATY WITH THE CHOCTAW AND CHICKASAW, 1854". Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904. 2:652-653 (accessed December 25, 2006).

- Kappler, Charles (ed.). "TREATY WITH THE CHOCTAW AND CHICKASAW, 1866". Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904. 2:918-931. (accessed December 27, 2006).

- Wright, Muriel H. "Organization of the Counties in the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations". Chronicles of Oklahoma 8:3 (September 1930) 315-334. (accessed December 26, 2006).

External links

- Chickasaw Nation, official website

- Chickasaw Nation Video Network - Chickasaw.TV

- Voices of Oklahoma interview with Bill Anoatubby. First person interview conducted on October 18, 2010 with Bill Anoatubby, the tribal Governor of the Chickasaw Nation.