Union Navy

The Union Navy was the United States Navy (USN) during the American Civil War, when it fought the Confederate States Navy (CSN). The term is sometimes used carelessly to include vessels of war used on the rivers of the interior while they were under the control of the United States Army, also called the Union Army.

Primary missions

The primary missions of the Union Navy were:

- 1. Maintain the blockade of Confederate ports by restraining all blockade runners; declared by President Lincoln on April 19, 1861, and continued until the end of the Rebellion.

- 2. Meet in combat the war vessels of the CSN.

- 3. Carry the war to places in the seceded states that were inaccessible to the Union Army, but could be reached by water.

- 4. Support the Army by providing both gunfire support and rapid transport and communications on the rivers of the interior.

Transformation

To accomplish these, the Union Navy had to undergo a profound transformation, both technical and institutional. During the war, sailing vessels were completely supplanted by ships propelled by steam for purposes of combat. Vessels of widely differing character were built from the keel up in response to peculiar problems they would encounter. Wooden hulls were at first protected by armor plating, and soon were replaced by iron or steel throughout. Guns were reduced in number, but increased in size and range; the reduction in number was partially compensated by mounting the guns in rotating turrets or by pivoting the gun on a curved deck track so they could be turned to fire in any direction.

The institutional changes that were introduced during the war were equally significant. The Bureau of Steam Engineering was added to the bureau system, testimony to the U.S. Navy's conversion from sail to steam. Most important from the standpoint of Army-Navy cooperation in joint operations, the set of officer ranks was redefined so that each rank in the U.S. Army had its equivalent in the U.S. Navy. The establishment of the ranks of admirals implied also a change of naval doctrine, from one favoring single-ship operations to that of employing whole fleets.

Ships

At the start of the war, the Union Navy had 42 ships in commission. Another 48 were laid up and listed as available for service as soon as crews could be assembled and trained, but few were appropriate for the task at hand. Most were sailing vessels, some were hopelessly outdated, and one (USS Michigan) served on Lake Erie and could not be moved to the ocean.[4] During the course of the war, the number in commission was increased by more than a factor 15, so that at the end the U.S. Navy had 671 vessels.[5]

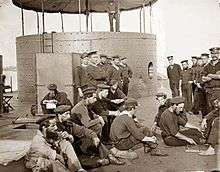

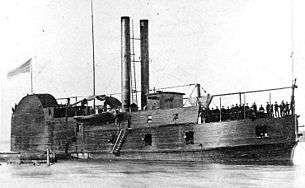

Even more significant than the increase in raw numbers was the variety of ship types that were represented, some of forms that had not been seen previously in naval war anywhere. The nature of the conflict, much of which took place in the interior of the continent or in rather shallow harbors along the coast, meant that vessels designed for use on the open seas were less useful than more specialized ships. To confront the forms of combat that came about, the federal government developed a new type of warship, the monitor, based on the original, USS Monitor.[6] The U.S. Navy took over a class of armored river gunboats created for the U.S. Army, but designed by naval personnel, the Eads gunboats.[7] So-called double-enders were produced to maneuver in the confined waters of the rivers and harbors.[8] The Union Navy experimented with submarines before the Confederacy produced its famed CSS Hunley; the result, USS Alligator failed primarily because of lack of suitable targets.[9] Building on Confederate designs, the Union Navy produced and used torpedo boats, small vessels that mounted spar torpedoes and were forerunners of both the modern torpedo and destroyer type of warship.[10]

Because of haste in their design and construction, most of the vessels taken into the U.S. Navy in this period of rapid expansion incorporated flaws that would make them unsuitable for use in a permanent system of defense. Accordingly, at the end of the war, most of them were soon stricken from the service rather than being mothballed. The number of ships at sea fell back to its prewar level.[11]

Ranks and rank insignia

1861–62

| Commissioned officer rank structure of the Union Navy[12] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Flag Officer | Captain | Commander | Lieutenant | Master |

| Epaulette |  |

|

|

| |

| Sleeve lace |  |

|

|

|

|

| Warrant and petty officer rank structure of the Union Navy[13] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Passed Midshipman | Midshipman | Boatswain / Gunner / Carpenter / Sailmaker | Master's mate | Rated Master's Mate |

| Epaulette |  |

None | None | None | None |

| Sleeve lace |  |

|

|

|

|

1862–64

| Commissioned officer rank structure of the Union Navy[14] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Rear admiral | Commodore | Captain | Commander | Lieutenant Commander |

Lieutenant | Master | Ensign |

| Insignia | .svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

|

|

.svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

.svg.png) | |

| Warrant and petty officer rank structure of the Union Navy[15] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Midshipman | Boatswain / Gunner / Carpenter / Sailmaker | Master's Mate | Rated Master's Mate |

| Insignia | .svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

|

1864–66

| Commissioned officer rank structure of the Union Navy[16][17] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Vice admiral | Rear admiral | Commodore | Captain | Commander | Lieutenant Commander |

Lieutenant | Master | Ensign | |

| Insignia |  Introduced in 1865 |

Introduced in 1865 |

.svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

| Warrant and petty officer rank structure of the Union Navy[18] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Midshipman | Boatswain / Gunner / Carpenter / Sailmaker | Master's Mate | Petty Officer |

| Insignia |  |

|

|

|

- Petty Officers

Chief Petty Officer

Master-at-Arms of the ship he serves in.[19]

Petty Officers of the Line

Rank and succession to command: [20]

- Boatswain's Mate

- Gunner's Mate

- Signal Quartermaster

- Cockswain to Commander-in-Chief

- Captain of Forecastle

- Cockswain

- Captain of Main-top

- Captain of Fore-top

- Captain of Mizzen-top

- Captain of Afterguard

- Quarter Gunner

- 2nd Captain of Forecastle

- 2nd Captain of Main-top

- 2nd Captain of Fore-top

- 2nd Captain of Mizzen-top

Petty Officers of the Staff

Rank next after Master-at-Arms: [19]

- Yeoman

- Surgeon's Steward

- Paymaster's Steward

- Master of the Band

- Schoolmaster

- Ship's Writer

Rank next after Gunner's Mate: [19]

- Carpenter's Mate

- Armorer

- Sailmaker's Mate

Rank next after Captain of the Afterguard: [19]

- Painter

- Cooper

- Armorer's Mate

Rank next after Quarter-Gunner: [19]

- Ship's Corporal

- Captain of the Hold

- Ship's Cook

- Baker

Institution

_poster.jpg)

The highest rank available to an U.S. naval officer when the war began was that of captain.[21] The Confederate constitution provided for the rank of admiral, but it was to be awarded for valor in battle. No Confederate officer was made admiral until Franklin Buchanan was named such after the Battle of Hampton Roads. This created problems when many ships had to operate together, with no clearly established chain of command. Even worse, when the Navy worked with the Army in joint operations, the customary rank equivalency between the two services meant that the naval captain, equivalent to an army colonel, would always be inferior to every army general present.[22] After the existing arrangement had been used for the first year of the war, the case was made that the interests of the nation would be better served by organizing the Navy along lines more like that of the Royal Navy of Great Britain. A set of officer ranks was established in the summer of 1862 that precisely matched the set of Army ranks.[23] The most visible change was that henceforth some individuals would be designated commodore, rear admiral, vice admiral, and finally admiral, all new formal ranks, and equivalent to, respectively, brigadier general, major general, lieutenant general, and general.[24]

A doctrinal shift took place at the same time. Prior to the war, the United States Navy emphasized single-ship operations, but the nature of the conflict soon made use of whole fleets necessary. Already at the Battle of Port Royal (7 November 1861), 77 vessels, including 19 warships, were employed.[25] This was the largest naval expedition that had ever sailed under the U.S. flag, but the record did not stand for long. Subsequent operations at New Orleans, Mobile, and several positions in the interior confirmed the importance of large fleets in modern naval operations.

The system of naval bureaus was revised in the summer of 1862. Some of the older bureaus were rearranged or had their names altered. The most radical change was the creation of the Bureau of Steam Engineering.[26] Its existence was testimony to the fact that the U.S. Navy would no longer rely upon the winds to propel its ships. More was involved in this decision than meets the eye, as the necessity of maintaining coaling stations around the globe meant that the nation had to rethink its attitude toward colonialism.

During the war the Union Navy had a total of 84,415 personnel. The Union Navy suffered 6,233 total casualties with 4,523 deaths from all causes. 2,112 Union sailors were killed by enemy action and 2,411 died by disease or injury. The Union Navy suffered at least 1,710 personnel wounded in action, injured, or disabled by disease.[27] The Union Navy started the war with 8,000 men, 7,600 enlisted men of all ratings and some 1,200 commissioned officers. The number of hands in the Union Navy grew five times its original strength at the war's outbreak. Most of these new hands were volunteers who desired to serve in the navy temporarily rather than make the navy a career as with many of the pre-war sailors. Most of these volunteers were rated as "Land's Men" by recruiters meaning they had little or no experience at sea in their civilian lives, although many sailors from the United States pre-war merchant marine joined the navy and they were often given higher ratings due to their background and experience.[28] A key part of the Union Navy's recruiting efforts was the offer of higher pay than a volunteer for the Union Army would receive and the promise of greater freedom or the opportunity to see more of the country and world. When the Draft was introduced the Navy tried to recruit volunteers by offering service at sea as a better paying alternative to being drafted into the Army, this incentive was especially meant to attract professional sailors who could be drafted the same as any other civilian and would rather see combat in an environment they were more familiar with.[29]

Sailors

Union sailors differed from their counterparts on land, soldiers. The sailors were typically unemployed, working-class men from urban areas, including recent immigrants. Unlike soldiers, few were farmers. They seldom enlisted to preserve the Union, end slavery, or display their courage; instead, many were coerced into joining.[30] According to Michael Bennett:

- The typical Union sailor was a hard, pragmatic, and cynical man who bore little patience for patriotism, reform, and religion. He drank too much, fought too much, and prayed too little. He preferred adventure to stability and went for quick and lucrative jobs rather than steady and slow employ under the tightening strictures of the new market economy. He was rough, dirty, and profane. Out of date before his time, he was aggressively masculine in a Northern society bent on gentling men. Overall, Union sailors proved less committed to emerging Northern values and were less ideological than soldiers for whom the broader issues of freedom, market success, and constitutional government proved constant touchstones during the war.[31]

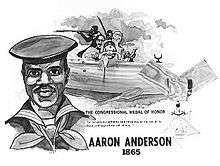

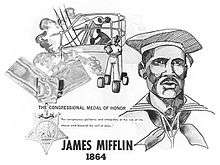

Nevertheless, Union navy sailors and marines were awarded 325 Medals of Honor for Civil War valor with immigrants receiving 39 percent of the awards: Ireland (50), England (25) and Scotland (13). [32]

Approximately 10,000, or around 17%, of Union Navy sailors were black;[1][2][33] seven of them were awarded the Medal of Honor.[3] The tension between white and "contraband" (black) sailors was high and remained serious during the war. Bennett argues:

- For the most part, white sailors rejected contrabands as sailors. They did so owing to a tangled mix of racial prejudices, unflattering stereotypes that equated sailors with slaves, and working-class people's fears of blacks as labor competition. The combination of all of these tensions eventually triggered a social war—referred to as "frictions" by sailors—as whites racially harassed, sometimes violently, former slaves serving alongside them.[34]

Blockade

The blockade of all ports in the seceded states was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln on 19 April 1861, one of the first acts of his administration following the bombardment of Fort Sumter.[35] It existed mostly on paper in the early days of the conflict, but became increasingly tighter as it continued. Although the blockade was never perfect,[36] it contributed to the isolation of the South and hastened the devaluation of its currency.

For administration of the blockade, the Navy was divided into four squadrons: the North Atlantic, South Atlantic, East Gulf, and West Gulf Blockading Squadrons.[37] (A fifth squadron, the Mississippi River Squadron, was created in late 1862 to operate in the Vicksburg campaign and its consequences; it was not involved with the blockade.)[38]

Invasion

Two early invasions of the South were meant primarily to improve the blockade, and then led to further actions. Following the capture of Cape Hatteras, much of eastern North Carolina was soon occupied by the Union Army.[39] The easy success in North Carolina was not repeated after the seizure of Port Royal in South Carolina, as determined resistance prevented significant expansion of the beachhead there. Charleston did not fall until the last days of the war.[40] The later capture of Fernandina, Florida, was intended from the start to provide a southern anchor for the Atlantic blockade. It led to the capture of Jacksonville and the southern sounds of Georgia, but this was not part of a larger scheme of conquest. It reflected mostly a decision by the Confederate government to retire from the coast, with the exception of a few major ports.[41] Late in the war, Mobile Bay was taken by fleet action, but there was no immediate attempt to take Mobile itself.

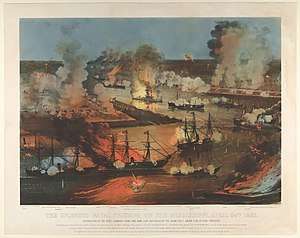

The capture of New Orleans was only marginally connected with the blockade, as New Orleans was already well sealed off.[42] It was important, however, for several other reasons. The passage of the forts below the city by Farragut's fleet showed that fixed fortifications could not defend against a fleet that was powered by steam, so it was crucial for the emergence of the Navy as equal to the Army in national defense. It also demonstrated the possibility of attacking the Confederacy along the line of the Mississippi River, and thus was an important, even vital, predecessor of the campaign that ultimately split the Confederacy. Finally, it cast doubt on the ability of the Confederacy to defend itself, and thus gave European nations reason not to grant diplomatic recognition.

The final important naval action of the war was the second assault on Fort Fisher, at the mouth of the Cape Fear River in North Carolina. It was one of the few actions of the war on the coast in which the Army and Navy cooperated fully.[43] The capture of the fort sealed off Wilmington, the last Confederate port to remain open. The death of the Confederacy followed in a little more than three months.

Battles

Coastal and ocean

- Hatteras Inlet

- Port Royal

- Burnside Expedition: Battle of Roanoke Island

- Hampton Roads

- New Orleans (Forts Jackson and St. Philip)

- Drewry's Bluff

- Galveston Harbor

- Charleston Harbor

- Fort Wagner (Morris Island)

- Albemarle Sound

- Sinking of CSS Alabama by the USS Kearsarge

- Mobile Bay

- First Battle of Fort Fisher

- Second Battle of Fort Fisher

- Trent's Reach

There were numerous small or one-to-one battles far away from the coasts between ocean-going Union vessels and blockade runners, often in the Caribbean but also in the Atlantic, the Battle of Cherbourg being the most famous example.

Inland waters

- Forts Henry and Donelson

- Island No. 10

- Plum Point Bend

- Memphis

- St. Charles, Arkansas (White River expedition)

- Vicksburg campaign

- Arkansas Post (Fort Hindman)

- Yazoo Pass Expedition

- Steele's Bayou Expedition

- Battle of Grand Gulf

- Red River expedition

Not included in this list are several incidents in which the Navy took part more or less incidentally. These include Shiloh and Malvern Hill. They are not put on the list because naval personnel were not involved in planning or preparation for the battle.

See also

- History of the United States Navy

- Confederate States Navy

- American Civil War

- Blockade runners of the American Civil War

- Bibliography of American Civil War naval history

Notes

- McPherson, James M.; Lamb, Brian (May 22, 1994). "James McPherson: What They Fought For, 1861-1865". Booknotes. C-SPAN. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

About 180,000 black soldiers and an estimated 10,000 black sailors fought in the Union Army and Navy, all of them in late 1862 or later, except for some blacks who enrolled in the Navy earlier.

- Loewen, James W. (2007). "John Brown and Abraham Lincoln". Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. New York: The New Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-56584-100-0. OCLC 29877812. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- Hanna, C. W. African American recipients of the Medal of Honor. p. 3. Note: Hanna includes Clement Dees in his count, while this list does not, because Dees's medal was rescinded.

- Soley, The blockade and the cruisers, Appendix A. The number of ships in commission should probably be reduced to 41, as one vessel, sloop USS Levant, had left Hawaii on 18 September 1860, bound for Aspinwall (present-day Colon, Panama), and was never seen again. See DANFS.

- Tucker, Blue and gray navies, p. 1.

- Gibbons, Warships and naval battles of the Civil War, pp. 24–25.

- Gibbons, Warships and naval battles of the Civil War, pp. 16–17.

- Gibbons, Warships and naval battles of the Civil War, pp. 106–107.

- Tucker, Blue and gray navies, pp. 267–268.

- Tucker, Blue and gray navies, pp. 260–261.

- Tucker, Blue and gray navies, p. 365.

- "Sea or Line Officers, 1861-July 31, 1862". Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "Cont". Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "Sea or Line Officers, July 31, 1862-January 28, 1864". Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "Cont". Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- US Navy (23 August 2017). "Uniform Regulations, 1866". Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Line Officers, January 28, 1864-1866". Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- Secretary of the Navy (1865). Regulations for the Government of the United States Navy. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, pp. 6, 372.

- Secretary of the Navy (1865), op.cit., p. 7.

- Secretary of the Navy (1865), op.cit., p. 6.

- Soley, The blockade and the cruisers,, pp. 1–6.

- By the same token, in combined operations with foreign fleets, no U.S. captain could command if a foreign admiral was present, no matter what the composition of the fleet. This was a purely hypothetical problem in the nineteenth century, as the United States did not ally itself with any foreign powers at that time.

- Soley, The Blockade and the cruisers, pp. 6–8.

- The principle of service equivalence is now so strongly established that it was applied without any particular thought when the additional ranks of General of the Army and Fleet Admiral were introduced at the same time following World War II.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, pp. 23–42.

- Tucker, Blue and gray navies, pp. 2–3.

- Leland, Anne and Mari-Jana Oboroceanu. American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Washington, DC, Congressional Research Service, February 26, 2010. Retrieved April 24, 2014. p. 2.

- McPherson, James M. War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861–1865 pp. 25-29

- http://www.ijnhonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/pdf_williams.pdf

- Michael J. Bennett, “Dissenters from the American Mood: Why Men Became Yankee Sailors During the Civil War.” North & South (2005) 8#2: 12–21.

- Michael J. Bennett (2005). Union Jacks: Yankee Sailors in the Civil War. U of North Carolina Press. p. x.

- ""Medal of Honor Recipients"". “US Army Center of Military History”.

- "Racism". www.friesian.com.

- Bennett, p. 150

- Civil War naval chronology, p. I-9.

- Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy, pp. 221–226.

- Tucker, Blue and gray navies, p. 4.

- Tucker, Blue and gray navies, p. 150.

- Browning, From Cape Charles to Cape Fear, pp. 27–36.

- Tucker, Blue and gray navies, p. 255.

- Browning, the success is all that was expected, pp. 66–73.

- Dufour, The night the war was lost, pp. 59–70.

- Browning, From Cape Charles to Cape Fear, pp. 293–297.

Further reading

- Anderson, Bern, By Sea and By River: The Naval History of the Civil War. Knopf, 1962. Reprint, Da Capo, 1989, ISBN 0-306-80367-4.

- Bennett, Michael J. Union Jacks: Yankee Sailors in the Civil War (2004). online

- Browning, Robert M. Jr., From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron During the Civil War. University of Alabama Press, 1993, ISBN 0-8173-5019-5.

- Browning, Robert M. Jr., Success is All That Was Expected: The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron During the Civil War. Brassey's, Inc., 2002, ISBN 1-57488-514-6 .

- Dufour, Charles L., The Night the War Was Lost. University of Nebraska Press, 1994, ISBN 0-8032-6599-9.

- Gibbon, Tony, Warships and Naval Battles of the Civil War. Gallery Books, 1989, ISBN 0-8317-9301-5.

- Jones, Virgil Carrington, The Civil War at Sea (3 vols.) Holt, 1960--2.

- Leland, Anne and Mari-Jana Oboroceanu. American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Washington, DC, Congressional Research Service, February 26, 2010. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- McPherson, James M. War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861–1865 (University of North Carolina Press; 2012) 277 pages.

- Musicant, Ivan, Divided Waters: The Naval History of the Civil War. HarperCollins, 1995, ISBN 0-06-016482-4.

- Ramold, Steven J. Slaves, Sailors, Citizens: African Americans in the Union Navy (2007) .

- Soley, James Russell, The Blockade and the Cruisers. C. Scribner's Sons, 1883; Reprint Edition, Blue and Grey Press, n.d.

- Tucker, Spencer, Blue and Gray Navies: The Civil War Afloat. Naval Institute Press, 2006, ISBN 1-59114-882-0.

- Wise, Stephen R., Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running During the Civil War, University of South Carolina Press, 1988, ISBN 0-87249-554-X.