Native American identity in the United States

Native American identity in the United States is an evolving topic based on the struggle to define "Native American" or "(American) Indian" both for people who consider themselves Native American and for people who do not. Some people seek an identity that will provide for a stable definition for legal, social, and personal purposes. There are a number of different factors which have been used to define "Indianness," and the source and potential use of the definition play a role in what definition is used. Facets which characterize "Indianness" include culture, society, genes/biology, law, and self-identity.[1] An important question is whether the definition should be dynamic and changeable across time and situation, or whether it is possible to define "Indianness" in a static way.[2] The dynamic definitions may be based in how Indians adapt and adjust to dominant society, which may be called an "oppositional process" by which the boundaries between Indians and the dominant groups are maintained. Another reason for dynamic definitions is the process of "ethnogenesis", which is the process by which the ethnic identity of the group is developed and renewed as social organizations and cultures evolve.[2] The question of identity, especially aboriginal identity, is common in many societies worldwide.[2]

The future of their identity is extremely important to Native Americans. Activist Russell Means spoke frequently about the crumbling Indian way of life, the loss of traditions, languages, and sacred places. He was concerned that there may soon be no more Native Americans, only "Native American Americans, like Polish Americans and Italian Americans." As the number of Indians has grown (ten times as many today as in 1890), the number who carry on tribal traditions shrinks (one fifth as many as in 1890), as has been common among many ethnic groups over time. Means said, "We might speak our language, we might look like Indians and sound like Indians, but we won’t be Indians."[3]

Definitions

There are various ways in which Indian identity has been defined. Some definitions seek universal applicability, while others only seek definitions for particular purposes, such as for tribal membership or for the purposes of legal jurisdiction.[4] The individual seeks to have a personal identity that matches social and legal definitions, although perhaps any definition will fail to categorize correctly the identity of everyone.[5]

American Indians were perhaps clearly identifiable at the turn of the 20th century, but today the concept is contested. Malcolm Margolin, co-editor of News From Native California muses, "I don’t know what an Indian is... [but] Some people are clearly Indian, and some are clearly not."[6] Cherokee Chief (from 1985–1995) Wilma Mankiller echoes: "An Indian is an Indian regardless of the degree of Indian blood or which little government card they do or do not possess."[7]

Further, it is difficult to know what might be meant by any Native American racial identity. Race is a disputed term, but is often said to be a social (or political) rather than biological construct. The issue of Native American racial identity was discussed by Steve Russell (2002, p68), "American Indians have always had the theoretical option of removing themselves from a tribal community and becoming legally white. American law has made it easy for Indians to disappear because that disappearance has always been necessary to the 'Manifest Destiny' that the United States span the continent that was, after all, occupied." Russell contrasts this with the reminder that Native Americans are "members of communities before members of a race."[8]

Traditional

Traditional definitions of "Indianness" are also important. There is a sense of "peoplehood" which links Indianness to sacred traditions, places, and shared history as indigenous people.[2] This definition transcends academic and legal terminology.[2] Language is also seen as an important part of identity, and learning Native languages, especially for youth in a community, is an important part in tribal survival.[9]

Some Indian artists find traditional definitions especially important. Crow poet Henry Real Bird offers his own definition, "An Indian is one who offers tobacco to the ground, feeds the water, and prays to the four winds in his own language." Pulitzer Prize-winning Kiowa author N. Scott Momaday gives a definition that is less spiritual but still based in the traditions and experience of a person and their family, "An Indian is someone who thinks of themselves as an Indian. But that's not so easy to do and one has to earn the entitlement somehow. You have to have a certain experience of the world in order to formulate this idea. I consider myself an Indian; I've had the experience of an Indian. I know how my father saw the world, and his father before him."[10]

Constructed as an imagined community

Some social scientists relate the uncertainty of Native American identity to the theory of the constructed nature of identity. Many social scientists discuss the construction of identity. Benedict Anderson's "imagined communities" are an example. However, some see construction of identity as being part of how a group remembers its past, tells its stories, and interprets its myths. Thus cultural identity is made within the discourses of history and culture. Identity thus may not be a fact based in the essence of a person, but a positioning, based in politics and social situations.[11]

Blood quantum

A common source of definition for an individual's being Indian is based on their blood (ancestry) quantum (often one-fourth) or documented Indian heritage. Almost two-thirds of all Indian federally recognized Indian tribes in the United States require a certain blood quantum for membership.[12] Indian heritage is a requirement for membership in most American Indian Tribes.[2] The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 used three criteria: tribal membership, ancestral descent, and blood quantum (one half). This was very influential in using blood quantum to restrict the definition of Indian.[13] The use of blood quantum is seen by some as problematic as Indians marry out to other groups at a higher rate than any other United States ethnic or racial category. This could ultimately lead to their absorption into the rest of multiracial American society.[14]

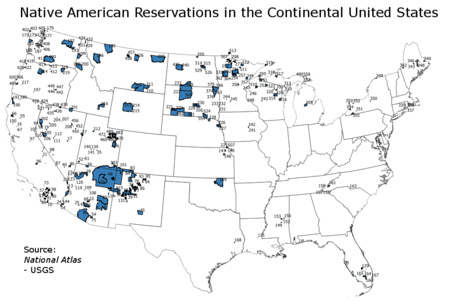

Residence on tribal lands

Related to the remembrance and practice of traditions is the residence on tribal lands and Indian reservations. Peroff (2002) emphasizes the role that proximity to other Native Americans (and ultimately proximity to tribal lands) plays in one's identity as a Native American.[15]

Construction by others

European conceptions of "Indianness" are notable both for how they influence how American Indians see themselves and for how they have persisted as stereotypes which may negatively affect treatment of Indians. The noble savage stereotype is famous, but American colonists held other stereotypes as well. For example, some colonists imagined Indians as living in a state similar to their own ancestors, for example the Picts, Gauls, and Britons before "Julius Caesar with his Roman legions (or some other) had ... laid the ground to make us tame and civil."[16]

In the 19th and 20th century, particularly until John Collier's tenure as Commissioner of Indian Affairs began in 1933, various policies of the United States federal and state governments amounted to an attack on Indian cultural identity and attempt to force assimilation. These policies included but were not limited to the banning of traditional religious ceremonies; forcing traditional hunter-gatherer people to begin farming, often on land that was unsuitable and produced few or no crops; forced cutting of hair; coercing "conversion" to Christianity by withholding rations; coercing Indian parents to send their children to boarding schools where the use of Native American languages was not permitted; freedom of speech restrictions; and restricted allowances of travel between reservations.[17] In the Southwest sections of the U.S. under Spanish control until 1810, where the majority (80%) of inhabitants were Indigenous, Spanish government officials had similar policies.[18]

United States government definitions

Some authors have pointed to a connection between social identity of Native Americans and their political status as members of a tribe.rev[19] There are 561 federally recognized tribal governments in the United States, which are recognized as having the right to establish their own legal requirements for membership.[20] In recent times, legislation related to Indians uses the "political" definition of identifying as Indians those who are members of federally recognized tribes. Most often given is the two-part definition: an "Indian" is someone who is a member of an Indian tribe and an "Indian tribe" is any tribe, band, nation, or organized Indian community recognized by the United States.

The government and many tribes prefer this definition because it allows the tribes to determine the meaning of "Indianness" in their own membership criteria. However, some still criticize this saying that the federal government's historic role in setting certain conditions on the nature of membership criteria means that this definition does not transcend federal government influence.[21] Thus in some sense, one has greater claim to a Native American identity if one belongs to a federally recognized tribe, recognition that many who claim Indian identity do not have.[22] Holly Reckord, an anthropologist who heads the BIA Branch of Acknowledgment and Recognition, discusses the most common outcome for those who seek membership: "We check and find that they haven't a trace of Indian ancestry, yet they are still totally convinced that they are Indians. Even if you have a trace of Indian blood, why do you want to select that for your identity, and not your Irish or Italian? It's not clear why, but at this point in time, a lot of people want to be Indian.".[23]

The Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 attempts to take into account the limits of definitions based in federally recognized tribal membership. In the act, having the status of a state-recognized Indian tribe is discussed, as well as having tribal recognition as an "Indian artisan" independent of tribal membership. In certain circumstances, this allows people who identify as Indian to legally label their products as "Indian made", even when they are not members of a federally recognized tribe.[24] In legislative hearings, one Indian artist, whose mother is not Indian but whose father is Seneca and who was raised on a Seneca reservation, said, "I do not question the rights of the tribes to set whatever criteria they want for enrollment eligibility; but in my view, that is the extent of their rights, to say who is an enrolled Seneca or Mohawk or Navajo or Cheyenne or any other tribe. Since there are mixed bloods with enrollment numbers and some of those with very small percentages of genetic Indian ancestry, I don't feel they have the right to say to those of us without enrollment numbers that we are not of Indian heritage, only that we are not enrolled.... To say that I am not [Indian] and to prosecute me for telling people of my Indian heritage is to deny me some of my civil liberties...and constitutes racial discrimination."[25]

Some critics believe that using federal laws to define "Indian" allows continued government control over Indians, even as the government seeks to establish a sense of deference to tribal sovereignty. Critics say Indianness becomes a rigid legal term defined by the BIA, rather than an expression of tradition, history, and culture. For instance, some groups which claim descendants from tribes that predate European contact have not been able to achieve federal recognition. On the other hand, Indian tribes have participated in setting policy with BIA as to how tribes should be recognized. According to Rennard Strickland, an Indian Law scholar, the federal government uses the process of recognizing groups to "divide and conquer Indians: "the question of who is 'more' or 'most' Indian may draw people away from common concerns."[26]

Self-identification

In some cases, one can self-identify about being Native American. For example, one can often choose to identify as Indian without outside verification when filling out a census form, a college application, or writing a letter to the editor of a newspaper.[2] A "self-identified Indian" is a person who may not satisfy the legal requirements which define a Native American according to the United States government or a single tribe, but who understands and expresses her own identity as Native American.[27] However, many people who do not satisfy tribal requirements identify themselves as Native American, whether due to biology, culture, or some other reason. The United States census allows citizens to check any ethnicity without requirements of validation. Thus, the census allows individuals to self-identify as Native American, merely by checking the racial category, "Native American/Alaska Native".[28] In 1990, about 60 percent of the more than 1.8 million persons identifying themselves in the census as American Indian were actually enrolled in a federally recognized tribe.[29] Using self identification allows both uniformity and includes many different ideas of "Indianness".[30] This is practiced by nearly half a million Americans who receive no benefits because

- they are not enrolled members of a federally recognized tribe, or

- they are full members of tribes which have never been recognized, or

- they are members of tribes whose recognition was terminated by the government during programs in the 1950s and 1960s.[21]

Identity is in some way a personal issue; based on the way one feels about oneself and one's experiences. Horse (2001) describes five influences on self-identity as Indian:

- "The extent to which one is grounded in one’s Native American language and culture, one’s cultural identity";

- "The validity of one’s American Indian genealogy";

- "The extent to which one holds a traditional American Indian general philosophy or worldview (emphasizing balance and harmony and drawing on Indian spirituality)";

- "One’s self-concept as an American Indian"; and

- "One’s enrollment (or lack of it) in a tribe."[31]

University of Kansas sociologist Joane Nagel traces the tripling in the number of Americans reporting American Indian as their race in the U.S. Census from 1960 to 1990 (from 523,591 to 1,878,285) to federal Indian policy, American ethnic politics, and American Indian political activism. Much of the population "growth" was due to "ethnic switching", where people who previously marked one group, later mark another. This is made possible by our increasing stress on ethnicity as a social construct.[32] In addition, since 2000 self-identification in US censuses has allowed individuals to check multiple ethnic categories, which is a factor in the increased American Indian population since the 1990 census.[33] Yet, self-identification is problematic on many levels. It is sometimes said, in fun, that the largest tribe in the United States may be the "Wantabes".[30]

Garroutte identifies some practical problems with self-identification as a policy, quoting the struggles of Indian service providers who deal with many people who claim ancestors, some steps removed, who were Indian. She quotes a social worker, "Hell, if all that was real, there are more Cherokees in the world than there are Chinese."[34] She writes that in self-identification, privileging an individual's claim over tribes' right to define citizenship can be a threat to tribal sovereignty.[35]

Personal reasons for self-identification

Many individuals seek broader definitions of Indian for personal reasons. Some people whose careers involve the fact that they emphasize Native American heritage and self-identify as Native American face difficulties if their appearance, behavior, or tribal membership status does not conform to legal and social definitions. Some have a longing for recognition. Cynthia Hunt, who self-identifies as a member of the state-recognized Lumbee tribe, says: "I feel as if I'm not a real Indian until I've got that BIA stamp of approval .... You're told all your life that you're Indian, but sometimes you want to be that kind of Indian that everybody else accepts as Indian."[36]

The importance that one "look Indian" can be greater than one's biological or legal status. Native American Literature professor Becca Gercken-Hawkins writes about the trouble of recognition for those who do not look Indian; "I self-identify as Cherokee and Irish American, and even though I do not look especially Indian with my dark curly hair and light skin, I easily meet my tribe's blood quantum standards. My family has been working for years to get the documentation that will allow us to be enrolled members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Because of my appearance and my lack of enrollment status, I expect questions regarding my identity, but even so, I was surprised when a fellow graduate student advised me—in all seriousness—to straighten my hair and work on a tan before any interviews. Thinking she was joking, I asked if I should put a feather in my hair, and she replied with a straight face that a feather might be a bit much, but I should at least wear traditional Native jewelry."[37]

Louis Owens, an unenrolled author of Choctaw and Cherokee descent, discusses his feelings about his status of not being a real Indian because he's not enrolled. "I am not a real Indian. ... Because growing up in different times, I naively thought that Indian was something we were, not something we did or had or were required to prove on demand. Listening to my mother's stories about Oklahoma, about brutally hard lives and dreams that cut across the fabric of every experience, I thought I was Indian."[38]

Historic struggles

Florida State anthropologist J. Anthony Paredes considers the question of Indianness that may be asked about pre-ceramic peoples (what modern archaeologists call the "Early" and "Middle Archaic" period), pre-maize burial mound cultures, etc. Paredes asks, "Would any [Mississippian high priest] have been any less awed than ourselves to come upon a so-called Paleo-Indian hunter hurling a spear at a woolly mastodon?" His question reflects the point that indigenous cultures are themselves the products of millennia of history and change.[39]

The question of "Indianness" was different in colonial times. Integration into Indian tribes was not difficult, as Indians typically accepted persons based not on ethnic or racial characteristics, but on learnable and acquirable designators such as "language, culturally appropriate behavior, social affiliation, and loyalty."[40] Non-Indian captives were often adopted into society, including, famously, Mary Jemison. As a side note, the "gauntlet" was a ceremony that was often misunderstood as a form of torture, or punishment but within Indian society was seen as a ritual way for the captives to leave their European society and become a tribal member.[40]

Since the mid-19th century, controversy and competition have worked both within and outside tribes, as societies evolved. In the early 1860s, novelist John Rollin Ridge led a group of delegates to Washington D.C. in an attempt to gain federal recognition for a "Southern Cherokee Nation" which was a faction that was opposed to the leadership of rival faction leader and Cherokee Chief John Ross.[41]

In 1911, Arthur C. Parker, Carlos Montezuma, and others founded the Society of American Indians as the first national association founded and run primarily by Native Americans. The group campaigned for full citizenship for Indians, and other reforms, goals similar to other groups and fraternal clubs, which led to blurred distinctions between the different groups and their members.[42] With different groups and people of different ethnicities involved in parallel and often competing groups, accusations that one was not a real Indian was a painful accusation for those involved. In 1918, Arapaho Cleaver Warden testified in hearings related to Indian religious ceremonies, "We only ask a fair and impartial trial by reasonable white people, not half-breeds who do not know a bit of their ancestors or kindred. A true Indian is one who helps for a race and not that secretary of the Society of American Indians."

In the 1920s, a famous court case was set to investigate the ethnic identity of a woman known as "Princess Chinquilla" and her associate Red Fox James (aka Skiuhushu).[43] Chinquilla was a New York woman who claimed to have been separated from her Cheyenne parents at birth. She and James created a fraternal club which was to counter existing groups "founded by white people to help the red race" in that it was founded by Indians. The club's opening received much praise for supporting this purpose, and was seen as authentic; it involved a Council Fire, the peace pipe, and speeches by Robert Ely, White Horse Eagle, and American Indian Defense Association President Haven Emerson. In the 1920s, fraternal clubs were common in New York, and titles such as "princess" and "chief" were bestowed by the club to Natives and non-Natives.[44] This allowed non-Natives to "try on" Indian identities.

Just as the struggle for recognition is not new, Indian entrepreneurship based on that recognition is not new. An example is a stipulation of the Creek Treaty of 1805 that gave Creeks the exclusive right to operate certain ferries and "houses of entertainment" along a federal road from Ocmulgee, Georgia to Mobile, Alabama, as the road went over parts of Creek Nation land purchased as an easement.[45]

Unity and nationalism

The issue of Indianness had somewhat expanded meaning in the 1960s with Indian nationalist movements such as the American Indian Movement. The American Indian Movement unified nationalist identity was in contrast to the "brotherhood of tribes" nationalism of groups like the National Indian Youth Council and the National Congress of American Indians.[46] This unified Indian identity has been cited to the teachings of 19th century Shawnee leader Tecumseh to unify all Indians against "white oppression."[47] The movements of the 1960s changed dramatically how Indians see their identity, both as separate from whites, as a member of a tribe, and as a member of a unified category encompassing all Indians.[48]

Examples

Different tribes have unique cultures, histories, and situations that have made particular the question of identity in each tribe. Tribal membership may be based on descent, blood quantum, and/or reservation habitation.

Cherokee

Historically, race was not a factor in the acceptance of individuals into Cherokee society, since historically, the Cherokee people viewed their self-identity as a political rather than racial distinction.[49] Going far back into the early colonial period, based upon existing social and historical evidence as well as oral history among the Cherokee themselves, the Cherokee society was best described as an Indian republic. Race and blood quantum are not factors in Cherokee Nation tribal citizenship eligibility (like the majority of Oklahoma tribes). To be considered a citizen in the Cherokee Nation, an individual needs a direct Cherokee by blood or Cherokee freedmen ancestor listed on the Dawes Rolls.[50] The tribe currently has members who also have African, Latino, Asian, white and other ancestry, and an estimated 75 percent of tribal members are less than one-quarter Indian by blood.[51] The other two Cherokee tribes, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, do have a minimum blood quantum requirement. Numerous Cherokee heritage groups operate in the Southeastern U.S..

Theda Perdue (2000) recounts a story from "before the American Revolution" where a black slave named Molly is accepted as a Cherokee as a "replacement" for a woman who was beaten to death by her white husband. According to Cherokee historical practices, vengeance for the woman's death was required for her soul to find peace, and the husband was able to prevent his own execution by fleeing to the town of Chota (where according to Cherokee law he was safe) and purchasing Molly as an exchange. When the wives family accepted Molly, later known as "Chickaw," she became a part of their clan (the Deer Clan), and thus Cherokee.[52]

Inheritance was largely matrilineal, and kinship and clan membership was of primary importance until around 1810, when the seven Cherokee clans began the abolition of blood vengeance by giving the sacred duty to the new Cherokee National government. Clans formally relinquished judicial responsibilities by the 1820s when the Cherokee Supreme Court was established. When in 1825, the National Council extended citizenship to biracial children of Cherokee men, the matrilineal definition of clans was broken and clan membership no longer defined Cherokee citizenship. These ideas were largely incorporated into the 1827 Cherokee constitution.[53] The constitution did, state that "No person who is of negro or mulatlo [sic]parentage, either by the father or mother side, shall be eligible to hold any office of profit, honor or trust under this Government," with an exception for, "negroes and descendants of white and Indian men by negro women who may have been set free."[54] Although by this time, some Cherokee considered clans to be anachronistic, this feeling may have been more widely held among the elite than the general population.[55] Thus even in the initial constitution, the Cherokee reserved the right to define who was and was not Cherokee as a political rather than racial distinction. Novelist John Rollin Ridge led a group of delegates to Washington, D.C., as early as the 1860s in an attempt to gain federal recognition for a "Southern Cherokee Nation" which was a faction that was opposed to the leadership of rival faction leader and Cherokee Chief John Ross.[41]

Navajo

Most of the 158,633 Navajos enumerated in the 1980 census and the 219,198 Navajos enumerated in the 1990 census were enrolled in the Navajo Nation, which is the nation with the largest number of enrolled citizens. It is notable as there is only a small number of people who identify as Navajo who are not registered.[56]

Lumbee

In 1952, Lumbee people who were organized under the name Croatan Indians voted to adopt the name of "Lumbee," for the Lumber River near their homelands. The US federal government acknowledged them as being Indians in the 1956 Lumbee Act but not as a federally recognized tribe.[57] The Act withheld the full benefits of federal recognition from the tribe.

Since then, the Lumbee people have tried to appeal to Congress for legislation to gain full federal recognition. Their effort has been opposed by several federally recognized tribes.[58][59]

When the Lumbee of North Carolina petitioned for recognition in 1974, many federally recognized tribes adamantly opposed them. These tribes made no secret of their fear that passage of the legislation would dilute services to historically recognized tribes.[60] The Lumbee were at one point known by the state as the Cherokee Indians of Robeson County and applied for federal benefits under that name in the early 20th century.[61] The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians has been at the forefront of the opposition of the Lumbee. It is sometimes noted that if granted full federal recognition, the designation would bring tens of millions of dollars in federal benefits, and also the chance to open a casino along Interstate 95 (which would compete with a nearby Eastern Cherokee Nation casino).[61]

References

- Garroutte (2003), Paredes (1995)

- Peroff (1997) p487

- Peroff (1997) p492

- Bowen (2000)

- Garroutte (2003)

- Peroff (1997) p489 quoting Fost (1991) p. 28

- Sheffield p107-108 quoted from Hales 1990b: 3A - Hales, Donna. 1990a "Tribe Touts Unregistered Artists", Muskogee (Okla.) Daily Phoenix, September 3, 1990 1A 10A

- Russell (2002) p68 is quoting López (1994) p55

- Etheridge (2007)

- Bordewich (1996) p67

- Hall (1997) p53

- Garroutte (2003) p16

- Brownell (2001) p284

- Peroff (1997) p487 gives the rate of interracial marriage for Native Americans as 75%, whites as 5% and blacks as 8%

- Peroff (2002) uses complexity theory methods to model the maintenance of traditions and self-identity based on proximity.

- quoted from Robert Johnson, promoter for the fledgling Virginia Colony in Dyar (2003) p819

- Russell (2002) p66-67

- Russell (2002) p67

- Ray (2007) p399

- This right was upheld by the US Supreme Court in Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez in 1978, which is discussed in Ray (2007) p403, see also "The U.S. Relationship To American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes". america.gov. Archived from the original on May 19, 2009. Retrieved February 8, 2006..

- Brownell (2001) p299

- Nagel remarks that 1,878,285 people marked Native American as their ethnicity on the 1990 US Census, while the number of members of federally recognized tribes is much smaller, Nagel (1995) p948

- Bordewich (1996) 66

- Brownell (2001) p313

- Brownell (2001) p314

- Brownell (2001) p302

- Garroutte (2003) p82

- Brownell (2001) p276-277 notes that much of the $180 billion dollars a year in federal money for the benefit of Indians are apportioned on the basis of this census population

- Thornton 1997, page 38

- Brownell (2001) p315

- Horse (2005) p65

- Nagel (1995) p948

- Russell 149

- Garroutte (2003) p83

- Garroutte (2003), p. 88

- Brownell (2001) p275

- Gercken-Hawkins (2003) p200

- Eva Marie Garroutte, Real Indians: identity and the survival of Native America, (2003), p. 14.

- Paredes (1995) p346

- Dyar (2003) p823

- Christiensen 1992

- Carpenter (2005) p141

- Carpenter (2005) p139

- Carpenter (2005) p143

- Paredes (1995) p357

- Bonney (1977) p210

- Particularly cited is Tecumseh's concern with the alienation of Indian lands and his 1812 statement about Indian unity as discussed in Bonney (1977) p229

- Schulz (1998)

- AIRFA Federal Precedence Applied in State Court "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2009-02-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Cherokee Nation > Home".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-09-22. Retrieved 2017-03-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Perdue (2000)

- Perdue (2000) p564

- Perdue (2000) p564-565

- Perdue (2000) p566

- Thornton 2004

- "1956 Lumbee Act". University of North Carolina, Pembroke. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- Karen I. Blu (1980). The Lumbee problem: the making of an American Indian people. University of Nebraska. ISBN 0803261977. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- Houghton, p.750.

- Brownell (2001) p304

- Barrett (2007)

Bibliography

- Barrett, Barbara. (2007) "Two N.C. tribes fight for identity; Delegation split on Lumbee recognition", The News & Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina) April 19, 2007

- Bonney, Rachel A. (1977) "The Role of AIM Leaders in Indian Nationalism." American Indian Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 3. (Autumn, 1977), pp. 209–224.

- Bordewich, Fergus M. (1996) Killing the White Man's Indian: Reinventing Native Americans at the End of the Twentieth Century. First Anchor Books, ISBN 0-385-42036-6

- Bowen, John R. (2000) "Should We Have a Universal Concept of 'Indigenous Peoples' Rights'?: Ethnicity and Essentialism in the Twenty-First Century" Anthropology Today, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Aug., 2000), pp. 12–16

- Brownell, Margo S. (2001) "Who is an Indian? Searching for an Answer to the Question at the Core of Federal Indian Law." Michigan Journal of Law Reform 34(1-2):275-320.

- Carpenter, Cari. (2005) "Detecting Indianness: Gertrude Bonnin's Investigation of Native American Identity." Wicazo Sa Review - Volume 20, Number 1, Spring 2005, pp. 139–159

- Carter, Kent. (1988) "Wantabes and Outalucks: Searching for Indian Ancestors in Federal Records". Chronicles of Oklahoma 66 (Spring 1988): 99-104 (Accessed June 30, 2007 here)

- Cohen, F. (1982) Handbook of Federal Indian law. Charlottesville: Bobbs-Merrill, ISBN 0-87215-413-0

- Dyar, Jennifer. (2003) "Fatal Attraction: The White Obsession with Indianness." The Historian, June 2003. Vol 65 Issue 4. pages 817–836

- Etheridge, Tiara. (2007) "Displacement, loss still blur American Indian identities" April 25, 2007, Wednesday, Oklahoma Daily, University of Oklahoma

- Field, W. Les (with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe). (2003) "Unacknowledged Tribes, Dangerous Knowledge, The Muwekma Ohlone and How Indian Identities Are 'Known.'" Wicazo Sa Review 18.2, pages 79–94

- Garroutte, Eva Marie. (2003) Real Indians: identity and the survival of Native America. University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-22977-0

- Gercken-Hawkins, Becca (2003) "'Maybe you only look white:' Ethnic Authority and Indian Authenticity in Academia." The American Indian Quarterly 27.1&2, pages 200-202

- Hall, Stuart. (1997) "The work of representation." In Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, ed. Stuart Hall, 15-75. London: Sage Publications, ISBN 0-7619-5432-5

- Horse, Perry G. (2005) "Native American identity", New Directions for Student Services. Volume 2005, Issue 109, Pages 61 – 68

- Lawrence, Bonita. (2003) "Gender, Race, and the Regulation of Native Identity in Canada and the United States: An Overview", Hypatia 18.2 pages 3–31

- Morello, Carol. (2001) "Native American Roots, Once Hidden, Now Embraced". Washington Post, April 7, 2001

- Nagel, J. (1995) "Politics and the Resurgence of American Indian Ethnic Identity", American Sociological Review 60: 947–965.

- Paredes, J. Anthony. (1995) "Paradoxes of Modernism and Indianness in the Southeast". American Indian Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 3. (Summer, 1995), pp. 341–360.

- Perdue, T. "Clan and Court: Another Look at the Early Cherokee Republic". American Indian Quarterly. Vol. 24, 4, 2000, p. 562

- Peroff, Nicholas C. (1997) "Indian Identity", The Social Science Journal, Volume 34, Number 4, pages 485-494.

- Peroff, N.C. (2002) "Who is an American Indian?", Social Science Journal, Volume 39, Number 3, pages 349

- Pierpoint, Mary. (2000) "Unrecognized Cherokee claims cause problems for nation". Indian Country Today. August 16, 2000 (Accessed May 16, 2007 here)

- Porter, F.W. III (ed.) (1983). "Nonrecognized American Indian tribes: An historical and legal perspective", Occasional Paper Series, No. 7. Chicago, IL: D’Arcy McNickle Center for the History of the American Indian, The Newberry Library.

- Ray, S. Alan. A Race or a Nation? Cherokee National Identity and the Status of Freedmen's Descendants. Michigan Journal of Race and Law, Vol. 12, 2007. Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol12/iss2/4.

- Russell, Steve. (2004) "Review of Real Indians: Identity and the Survival of Native America", PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review. May 2004, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 147–153

- Russell, Steve (2002). "Apples are the Color of Blood", Critical Sociology, Vol. 28, 1, 2002, p. 65

- Schulz, Amy J. (1998) "Navajo Women and the Politics of Identity", Social Problems, Vol. 45, No. 3. (Aug., 1998), pp. 336–355.

- Sturm, Circe. (1998) "Blood Politics, Racial Classification, and Cherokee National Identity: The Trials and Tribulations of the Cherokee Freedmen". American Indian Quarterly, Winter/Spring 1998, Vol 22. No 1&2 pgs 230-258

- Thornton, Russell. (1992) The Cherokees: A Population History. University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-9410-7

- Thornton, Russell. (1997) "Tribal Membership Requirements and the Demography of 'Old' and 'New' Native Americans". Population Research and Policy Review, Vol. 16, Issue 1, p. 33 ISBN 0-8032-4416-9

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-18. American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States: 2000" United States Census Bureau, Census 2000, Special Tabulation (Accessed May 27, 2007 here)