Kickapoo people

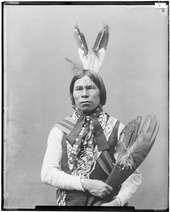

The Kickapoo People (Kickapoo: Kiikaapoa or Kiikaapoi; Spanish: Kikapú) are an Algonquian-speaking Native American and Indigenous Mexican tribe, originating in the region south of the Great Lakes. Today, there are three federally recognized Kickapoo tribes in the United States: Kickapoo Tribe of Indians of the Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas, the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, and the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas. The Oklahoma and Texas bands are politically associated with each other. The Kickapoo in Kansas came from a relocation from southern Missouri in 1832 as a land exchange from their reserve there.[1] Around 3,000 people are enrolled tribal members. Another band, the Tribu Kikapú, resides in Múzquiz Municipality in the Mexican state of Coahuila. Smaller bands live in Sonora and Durango.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Roughly 5,000 (3,000 enrolled members) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Spanish, Kickapoo | |

| Religion | |

| Native American Church; Christianity (many Catholic, some Protestant); tribal religious practices | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Sauk, Fox, other Algonquian peoples |

Name and etymology

According to some sources, the name "Kickapoo" (Giiwigaabaw in the Anishinaabe language and its Kickapoo cognate Kiwikapawa) means "stands here and there," which may have referred to the tribe's migratory patterns. The name can also mean "wanderer". This interpretation is contested and generally believed to be a folk etymology.

History

The Kickapoo are an Algonquian-language people who likely migrated to or developed as a people in a large territory along the Wabash River in the area of modern Terre Haute, Indiana. They were confederated with the larger Wabash Confederacy, which included the Piankeshaw to their south, the Wea to their north, and the powerful Miami Tribe, to their east. A subgroup occupied the Upper Iowa River region in what was later known as northeast Iowa and the Root River region in southeast Minnesota in the late 1600s and early 1700s. This group was probably known by the clan name "Mahouea", derived from the Illinoian word for wolf, m'hwea.[2]

The earliest European contact with the Kickapoo tribe occurred during the La Salle Expeditions into Illinois Country in the late 17th century. The French colonists set up remote fur trading posts throughout the region, including on the Wabash River. They typically would set up posts at or near Native American villages, and Terre Haute was founded as a French village. The Kickapoo had to contend with a changing cast of Europeans; the British defeated the French in the Seven Years' War and took over nominal rule of this area after 1763. They increased their own trading with the Kickapoo.

The United States acquired this territory east of the Mississippi River and north of the Ohio River after it gained independence from the United Kingdom. As white settlers moved into the region from the United States eastern areas, beginning in the early 19th century, the Kickapoo were under pressure. They negotiated with the United States over their territory in several treaties, including the Treaty of Vincennes, the Treaty of Grouseland, and the Treaty of Fort Wayne. They sold most of their lands to the United States and moved north to settle among the Wea.

Rising tensions between the regional tribes and the United States led to Tecumseh's War in 1811. The Kickapoo were one of Tecumseh's closest allies. Many Kickapoo warriors participated in the Battle of Tippecanoe and the subsequent War of 1812 on the side of the British, hoping to expel the American settlers from the region. A prominent, nonviolent spiritual leader among the Kickapoo was Kennekuk, who led his followers during Indian Removal in the 1830s to their current tribal lands in Kansas. He died there in 1852.

The close of the war led to a change of federal Indian policy in the Indiana Territory, and later the state of Indiana. American leaders began to advocate the removal of tribes to lands west of the Mississippi River, to extinguish their claims to lands wanted by American settlers. The Kickapoo were among the first tribes to leave Indiana under this program. They accepted land in Kansas and an annual subsidy in exchange for leaving the state.

Language

| Kickapoo | |

|---|---|

Algic

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | kic |

| Glottolog | kick1244[3] |

Kickapoo speak an Algonquian language closely related to that of the Sauk and Fox. They are classified with the Central Algonquians, and are also related to the Illinois Confederation.

In 1985 the Kickapoo Nation's School in Horton, Kansas, began a language immersion program for elementary school grades to revive teaching and use of the Kickapoo language in grades K-6.[4] Efforts in language education continue at most Kickapoo sites. In 2010, the Head Start Program at the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas (KTTT) reservation, which teaches the Kickapoo language, became "the first Native American school to earn Texas School Ready! (TSR) Project certification."[5]

Also in 2010, Mexico's "Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) participated in the elaboration of a Kickapoo alphabet that may be used by more than 700 members of the group that dwell in Mexico and the United States, in the states of Coahuila and Texas. Previously no Kickapoo alphabet was used in Mexico; although there is a syllabic writing system it has no element ordination, organization or classification method."[6] The Kickapoo in Mexico are known for their whistled speech.

Texts,[7] recordings,[8] and a vocabulary[9] of the language are available.

The Kickapoo language and members of the Kickapoo tribe were featured in the movie The Only Good Indian (2009), directed by Greg Wilmott and starring Wes Studi. This was a fictionalized account of Native American children forced to attend an Indian boarding school, where they were forced to speak English and give up their cultures.[10]

Sounds

There are eleven consonant phonemes in Kickapoo:

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar/ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | p | t | tʃ | k | ||

| Fricative | θ | s | h | |||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||

| Approximant | j | w |

The voiceless sounds can sometimes be voiced as [b, d, dʒ, ɡ, ð, z], but infrequently. Some speakers may pronounce /tʃ/ as [ts].

The eight vowel sounds in Kickapoo are as follows: short /a, ɛ, i, o/ and long /aː, ɛː, iː, oː/. Three of the vowels /a, ɛ, o/, have allophones: [ə, ɪ, ʊ~u].[11]

Tribes and communities

There are three federally recognized Kickapoo communities in the United States: one in Kansas, one in Texas, and the third in Oklahoma. The Mexican Kickapoo are closely tied to the Texas and Oklahoma communities. These groups migrate annually among the three locations to maintain connections. Indeed, the Texas and Mexican branch are the same cross-border nation, called Kickapoo of Coahuila/Texas [12]

Kickapoo Indian Reservation of Kansas

The tribe in Kansas was home to prophet Kenekuk. Kenekuk was known for his astute leadership that allowed the small group to maintain their reservation. Kenekuk wanted to keep order among the tribe he was in, whilst living in Kansas. He also wanted to focus on keeping the identity of the Kickapoo people, because of all the relocating that they that to do.[13]

The basis of Kenekuk's leadership began in the religious revivals of the 1820s and 1830s, with a blend of Protestantism and Catholicism. Kenekuk taught his tribesmen and white audiences to obey gods commands for sinners were damned to the pits of hell.[13] Once the Kickapoo people got relocated to Kansas they resisted the ideas of Protestantism and Catholicism and started focusing more on farming, so they could provide food for the rest of the tribe. After this had happened they remained together and claimed some of the original land that they had before it was taken by Americans.

The Kickapoo Indian Reservation of Kansas is located at 39°40′51″N 95°36′41″W in the northeastern part of the state in parts of three counties: Brown, Jackson, and Atchison. It has a land area of 612.203 square kilometres (236.373 sq mi) and a resident population of 4,419 as of the 2000 census. The largest community on the reservation is the city of Horton. The other communities are:

Kickapoo Indian Reservation of Texas

The Kickapoo Indian Reservation of Texas is located at 28°36′37″N 100°26′19″W on the Rio Grande on the U.S.-Mexico border in western Maverick County, just south of the city of Eagle Pass, as part of the community of Rosita South. It has a land area of 0.4799 square kilometres (118.6 acres) and a 2000 census population of 420 persons. The Texas Indian Commission officially recognized the tribe in 1977.[14]

Other Kickapoo in Maverick County, Texas, constitute the "South Texas Subgroup of the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma". That band owns 917.79 acres (3.7142 km2) of non-reservation land in Maverick County, primarily to the north of Eagle Pass. It has an office in that city.[15]

Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma

After being expelled from the Republic of Texas, many Kickapoo moved south to Mexico, but the population of two villages settled in Indian Territory. One village settled within the Chickasaw Nation and the other within the Muscogee Creek Nation. These Kickapoo were granted their own reservation in 1883 and became recognized as the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma.

The reservation was short-lived. In 1893 under the Dawes Act, their communal tribal lands were broken up[16] and assigned to separate member households by allotments. The tribe's government was dismantled by the Curtis Act of 1898, which encouraged assimilation by Native Americans to the majority culture. Tribal members struggled under these conditions.

In the 1930s the federal and state governments encouraged tribes to reorganize their governments. This one formed the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma in 1936, under the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act.[17]

Today the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma is headquartered in McLoud, Oklahoma. Their tribal jurisdictional area is in Oklahoma, Pottawatomie, and Lincoln counties. They have 2,719 enrolled tribal members.[18]

See also

Notes

- KICKAPOO HISTORY

- Colin M., Betts. "Rediscovering the Mahouea". Journal of the Iowa Archeological Society 58:23-33. Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Kickapoo". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Reaves, Michell Reaves (2001-08-11). "Canku Ota - Aug. 11, 2001 - Indians Value Their Language". Canku Ota (Many Paths), an Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America, Medill News Service (42). Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- "Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas First Native American Tribe to Achieve Texas School Ready! Certification". Newswise, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. 2010-01-26. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- "Kickapoo Language Prepared to be Written". Art Daily. 2010-04-12. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- "OLAC resources in and about the Kickapoo language". Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- "Recordings for study of the Shawnee, Kickapoo, Ojibwa, and Sauk-and-Fox :: American Philosophical Society". Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- "OLAC Record: Kickapoo vocabulary". 1988. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- "Kickapoo Language, Culture to be Featured in Film". Hiawatha World Online. 2007-09-12. Archived from the original on 2012-08-10. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- Voorhis, Paul H. (1974). Introduction to the Kickapoo Language. Indiana University Publications.

- Mager, Elisabeth (2011). "The Kickapoo Of Coahuila/Texas Cultural Implications Of Being A Cross-Border Nation" (PDF). Voices of Mexico (90): 36–40.

- Herring, Joseph B. (Summer 1985). "Kenekuk, the Kickapoo Prophet: Acculturation without Assimilation". American Indian Quarterly. 9 (3): 295–307. doi:10.2307/1183831. JSTOR 1183831.

- Miller, Tom. On the Border: Portraits of America's Southwestern Frontier, pp. 67.

- Maverick County Appraisal District property tax appraisals, 2007

- Withington, W.R. (1952). "Kickapoo Titles in Oklahoma". 23 Oklahoma Bar Association Journal 1751. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- Annette Kuhlman, "Kickapoo" Archived 2014-12-30 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture, Oklahoma Historical Society, 2009 (accessed 21 February 2009)

- Oklahoma Indian Affairs. Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory. Archived 2009-02-11 at the Wayback Machine, 2008:21

Further reading

- Grant Foreman, The Last Trek of the Indians: An Account of the Removal of the Indians from North of the Ohio River, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1946

- Arrell M. Gibson, The Kickapoo: Lords of the Middle Border, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963

- Mager Elisabeth (2017) Ethnic Consciousness in Cultural Survival: The Morongo Band of Mission Indians and the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas . American Indian Culture and Research Journal: 2017, Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 47–72.

- M. Christopher Nunley, "Kickapoo Indians," in The New Handbook of Texas, Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1996.

- Muriel H. Wright, A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986

- Joseph B. Herring, Kennekuk: The Kickapoo Prophet, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1988

External links

- Kickapoo Tribe of Kansas, official website

- Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, official website

- Kickapoo language, alphabet and pronunciation

- Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas, official website

- Matthew R. Garrett, Kickapoo Foreign Policy, 1650–1830, PhD dissertation, University of Nebraska, 2006, at Digital Commons

- Kickapoo Reservation, Kansas and Kickapoo Reservation, Texas United States Census Bureau

- "First Nations: Kickapoo", Lee Sultzman Tolatsga]

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.