Creek War

The Creek War (1813–1814), also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, was a regional war between opposing Creek factions, European empires and the United States, taking place largely in today's Alabama and along the Gulf Coast. The major conflicts of the war took place between state militia units and the "Red Stick" Creeks.

| Creek War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of War of 1812 and American Indian Wars | |||||||

William Weatherford surrendering to Andrew Jackson | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Lower Creeks Cherokee Choctaw | Red Stick Creek | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Andrew Jackson John Coffee William McIntosh Pushmataha Mushulatubbee |

William Weatherford Menawa Peter McQueen | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 7,000 | 4,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

~584 killed, unknown wounded |

~1,597 killed, unknown wounded | ||||||

The Creek War was part of the centuries-long American Indian Wars. It is usually considered part of the War of 1812 because it was influenced by Tecumseh's War in the Old Northwest, was concurrent with the American-British war and involved many of the same participants, and the Red Sticks had sought British support and aided Admiral Cochrane's advance towards New Orleans.

The Creek War began as a conflict within the Creek Confederation, but local white militia units quickly became involved. British traders in Florida as well as the Spanish government provided the Red Sticks with arms and supplies because of their shared interest in preventing the expansion of the United States into their areas. The United States government formed an alliance with the Choctaw Nation and Cherokee Nation (the traditional enemies of the Creeks), along with the remaining Creeks to put down the rebellion.

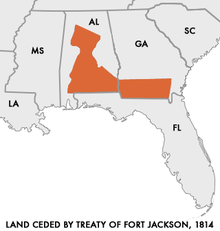

The war effectively ended with the Treaty of Fort Jackson (August 1814), when General Andrew Jackson forced the Creek confederacy to surrender more than 21 million acres in what is now southern Georgia and central Alabama.[1]

Background

The Red Stick militancy was a response to the increasing United States cultural and territorial encroachment into their traditional lands. The alternate designation as the Creek Civil War comes from the divisions within the tribe over cultural, political, economic, and geographic matters. At the time of the Creek War, the Upper Creeks controlled the Coosa, Tallapoosa, and Alabama Rivers that led to Mobile, while the Lower Creeks controlled the Chattahoochee River, which flowed into Apalachicola Bay. The Lower Creek were trading partners with the United States and, unlike the Upper Creeks, had adopted more of their cultural practices.[2]

Territorial conflict

The provinces of East and West Florida were governed by the Spanish, and British firms like Panton, Leslie, and Co. provided most of the trade goods into Creek country. Pensacola and Mobile, in Spanish Florida, controlled the outlets of the US Mississippi Territory's (established 1798) rivers.[3]

Territorial conflicts between France, Spain, Britain, and the United States along the Gulf Coast that had previously helped the Creeks to maintain control over most of the United States' southwestern territory had shifted dramatically due to the Napoleonic Wars, the Florida Rebellion, and the War of 1812. This made long-standing Creek trade and political alliances more tenuous than ever.

During and after the American Revolution, the United States wished to maintain the Indian Line which had been established by the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The Indian Line created a boundary for colonial settlement in order to prevent illegal encroachment into Indian lands, and also helped the U.S. government maintain control over the Indian trade. Traders and settlers often violated the terms of the treaties establishing the Indian Line, and frontier settlements by colonials in Indian lands was one of the arguments the United States used to expand its territory.

In the Treaty of New York (1790), Treaty of Colerain (1796), Treaty of Fort Wilkinson (1802), and the Treaty of Fort Washington (1805), the Creek ceded their Georgia territory east of the Ocmulgee River. In 1804, the United States claimed the city of Mobile under the Mobile Act. The 1805 treaty with the Creek had also allowed the creation of a Federal Road that linked Washington to the newly acquired port city of New Orleans, which partially stretched through Creek territories.

These increasing territorial grabs westward into Creek territory (which included parts of Spanish Florida), coupled with the Louisiana Purchase (which neither the British nor the Spanish recognized at the time), compelled the British and Spanish governments to strengthen existing alliances with the Creek. In 1810, following the occupation of Baton Rouge during the West Florida Rebellion, the United States sent an expeditionary force to occupy Mobile. As a result, Mobile was jointly occupied by weak American and Spanish soldiers until Secretary of War John Armstrong ordered General James Wilkinson to force the Spanish to turn over control of the city in February 1813.

The Patriot Army captured parts of East Florida from 1811–1815. After Fort Charlotte was surrendered in April, the Spanish focused on protecting Pensacola from the United States.[4] The Spanish decided to support the Creek in an attack on the United States and in defense of their homeland, but were greatly hindered by their weak position in the Floridas and lack of supplies even for their own army.

Cultural assimilation and religious revival

The splintering of the Creek peoples along progressive and nativist lines had roots dating back to the eighteenth century, but came to a head after 1811.[5] Red Stick militancy was a response to the economic and cultural crises in Creek society caused by the adoption of Western trade goods and culture. From the sixteenth century, the Creek had formed successful trade alliances with European empires, but the drastic fall in the price of deerskin from 1783 to 1793 made it more difficult for individuals to repay their debt, while at the same time the assimilation process made American goods more necessary.[6] The Red Sticks particularly resisted the civilization programs administered by the U.S. Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins, who had stronger alliances among the towns of the Lower Creek. Some of the "progressive" Creek began to adopt American farming practices as their game disappeared, and as more Anglo settlers assimilated into Creek towns and families.[7]

Leaders of the Lower Creek towns in present-day Georgia included Bird Tail King (Fushatchie Mico) of Cusseta; Little Prince (Tustunnuggee Hopoi) of Broken Arrow, and William McIntosh (Tunstunuggee Hutkee, White Warrior) of Coweta.[7] Many of the most prominent Creek chiefs before the Creek War were "mixed-bloods" like William McGillivray and William McIntosh (who were on opposing sides of the Creek Civil War).

Before the Creek War and the War of 1812, most US politicians saw removal to be the only alternative to the assimilation of native peoples into Western culture. The Creeks, on the other hand, blended their own culture with adopted trade goods and political terms, and had no intention of abandoning their land.[8]

The Americanization of the Creeks was more prevalent in western Georgia among the Lower Creeks than in Upper Creek Towns, and came from internal and external processes. The US government's and Benjamin Hawkins' pressure on the Creeks to assimilate stood in contrast to the more natural blending of cultures that came from a long tradition of cohabitation and cultural appropriation, beginning with white traders in Indian country.[9]

The Shawnee leader Tecumseh came to the area to encourage the peoples to join his movement to throw the Americans out of Native American territories. He had united tribes in the Northwest (Ohio and related territories) to fight against US settlers after the War for Independence. In 1811, Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa attended the annual Creek council at Tukabatchee. Tecumseh delivered an hour-long speech to an audience of 5,000 Creeks as well as an American delegation including Hawkins. Although the Americans dismissed Tecumseh as non-threatening, his message of resistance to Anglo encroachment was well received among Creek and Seminole, especially among more conservative/traditional elders and young men.[10]

Mobilization of recruits to Tecumseh's cause was bolstered by the Great Comet of 1811 and the New Madrid earthquakes of 1811–12, which were taken as evidence of Tecumseh's supernatural powers. The war party rallied around prophets who had traveled with Tecumseh, and remained with the Creek, and influenced newly converted Creek religious leaders.[11] Peter McQueen of Talisi (now Tallassee, Alabama); Josiah Francis (Hillis Hadjo) (Francis the Prophet) of Autaga, a Koasati town; and High-head Jim (Cusseta Tustunnuggee) and Paddy Walsh, both Alabamas, were among the spiritual leaders responding to rising concerns and the prophetic message.[12] The militant faction of Creek stood in opposition of the Creek Confederacy Council's official policies, particularly in regard to foreign relations with the United States. The rising war party began to be called Red Sticks at this time. (In Creek culture, red 'sticks' or war clubs symbolize war while white sticks represent peace.)[13]

Course of the war

Creeks who did not support the war became targets for the prophets and their followers, and began to be murdered in their sleep or burned alive.[11] Warriors of the prophets' party also began to attack the property of their enemies, burning plantations and destroying livestock.[14] The first major offensive of the civil war was the Red Stick attack on the Upper Creek town, and seat of the council, at Tuckabatchee on July 22, 1813.[5]

In Georgia, a war party of "friendly" Creek organized under William McIntosh, Big Warrior, and Little Prince attacked 150 Uchee warriors who were traveling to meet up with Red Stick Creeks in the Mississippi Territory. After this offensive in the beginning of October 1813, the party burned a number of Red Stick towns before retiring to Coweta.[15]

Although there were a few limited attacks on whites in 1812 and early 1813, Hawkins did not believe that the disruption in the Creek Nation or the increasing war dances were a cause for concern. In one instance in February 1813, a small war party of Red Sticks, led by Little Warrior, were returning from Detroit when they killed two families of settlers along the Ohio River. Hawkins demanded that the Creek turn over Little Warrior and his six companions, standard operating procedure between the nations up to that point.[16]

The first clashes between the Red Sticks and United States forces occurred on July 21, 1813. A group of territorial militia intercepted a party of Red Sticks returning from Spanish Florida, where they had acquired arms from the Spanish governor at Pensacola. The Red Sticks escaped and the soldiers looted what they found. Seeing the Americans looting, the Creek regrouped and attacked and defeated the Americans. The Battle of Burnt Corn, as the exchange became known, broadened the Creek Civil War to include American forces.[17]

Chiefs Peter McQueen and William Weatherford led an attack on Fort Mims, north of Mobile, on August 30, 1813. The Red Sticks' goal was to strike at mixed-blood Creek of the Tensaw settlement who had taken refuge at the fort. The warriors attacked the fort, and killed a total of 400 to 500 people, including women and children and numerous white settlers. The attack became known as the Fort Mims Massacre and became a rallying cause for American militia.[18]

The Red Sticks subsequently attacked other forts in the area, including Fort Sinquefield. Panic spread among settlers throughout the Southwestern frontier, and they demanded US government intervention. Federal forces were busy fighting the British and Northern Woodland tribes, led by the Shawnee chief Tecumseh in the Northwest. Affected states called up militias to deal with the threat.

After the Battle of Burnt Corn, U.S. Secretary of War John Armstrong notified General Thomas Pinckney, Commander of the 6th Military District, that the U.S. was prepared to take action against the Creek Confederacy. Furthermore, if Spain were found to be supporting the Creeks, an assault on Pensacola would ensue.[19]

Brigadier General Ferdinand Claiborne, a militia commander in the Mississippi Territory, was concerned about the weakness of his sector on the western border of the Creek territory, and advocated preemptive strikes. But Major General Thomas Flournoy, commander of 7th Military District, refused his requests. He intended to carry out a defensive American strategy. Meanwhile, settlers in that region sought refuge in blockhouses.[20]

The Tennessee legislature authorized Governor Willie Blount to raise 5,000 militia for a three-month tour of duty. Blount called out a force of 2,500 West Tennessee men under Colonel Andrew Jackson to "repel an approaching invasion ... and to afford aid and relief to ... Mississippi Territory".[21] He also summoned a force of 2,500 from East Tennessee under Major General John Alexander Cocke. Jackson and Cocke were not ready to move until early October.[22]

In addition to the state actions, U.S. Indian Agent Hawkins organized the friendly (Lower Town) Creek under Major William McIntosh, an Indian chief, to aid the Georgia and Tennessee militias in actions against the Red Sticks. At the request of Chief Federal Agent Return J. Meigs (called White Eagle by the Indians for the color of his hair), the Cherokee Nation voted to join the Americans in their fight against the Red Sticks. Under the command of Chief Major Ridge, 200 Cherokee fought with the Tennessee Militia under Colonel Andrew Jackson.

At most, the Red Stick force consisted of 4,000 warriors, possessing perhaps 1,000 muskets. They had never been involved in a large-scale war, not even against neighboring American Indians. Early in the war, General Cocke observed that arrows "form a very principal part of the enemy's arms for warfare, every man having a bow with a bundle of arrows, which is used after the first fire with the gun until a leisure time for loading offers."[23] Many Creek tried to remain friendly to the United States; but, after Fort Mims, few European Americans in the region distinguished between friendly and unfriendly Creeks.[24]

The Holy Ground (Econochaca), located near the junction of the Alabama and Coosa Rivers, was the heart of the Red Stick Confederation.[25] It was about 150 miles (240 km) from the nearest supply point available to any of the three American armies. The easiest attack route was from Georgia through the line of forts on the frontier and then along a good road that led to the Upper Creek towns near the Holy Ground, including nearby Hickory Ground. Another route was north from Mobile along the Alabama River. Jackson's route of advance was south from Tennessee through a mountainous and pathless terrain.[26]

Georgia campaign

By August, the Georgia Volunteer Army and state militia had been mobilized in anticipation of war with the Creeks. The news of Fort Mims first reached Georgia on September 16, and was taken as legal grounds to begin a military offensive.[27] In addition, Benjamin Hawkins wrote to Floyd on September 30 that the Red Stick war party had "received 25 small guns" at Pensacola.[28] The immediate concern of the force was the defense of Georgia's "Indian Line", separating Indian territory from U.S. territory at the Ocmulgee River.

The proximity of Jasper and Jones counties to hostile Creek towns resulted in a regiment of Georgia volunteer militia under Major General David Adams. John Floyd was made general of the main Georgia army (in September 1812 and numbering 2,362 men). The Georgia Army was aided by Cherokee and independent Creek allies, as well as a number of Georgia volunteer militia. Floyd's task was to advance to the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers and join the Army of Tennessee.[29]

Due to the state's failure to secure supplies early enough in the year, Floyd gained a few months to train and drill the men at Fort Hawkins. On November 24, General Floyd crossed the Chattahoochee and established Fort Mitchell, where he was joined by 300-400 Creek from Coweta, organized under McIntosh. With these allies and 950 of his men, Floyd began his advance towards the juncture of the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers where he was supposed to rendezvous with Jackson. His first target was the major town of Autossee on the Tallapoosa River, a Red Stick stronghold only 20 miles from the Coosa River.[30] On November 29, he attacked Autossee. Floyd's losses were 11 killed and 54 wounded. Floyd estimated that 200 Creek were killed.[31] Having achieved the destruction of the town, Floyd returned to Fort Mitchell.

The second westward advance of Floyd's troops departed Fort Mitchell with a force of 1,100 militia and 400 friendly Creek. Along the way they fortified Fort Bainbridge and Fort Hull on the federal road. On January 26, 1813, they set up a camp on the Callabee Creek near the abandoned site of Autossee. Red Stick chiefs William Weatherford, Paddy Walsh, High-head Jim, and William McGillivray raised a combined force of at least 1,300 warriors to stop the advance. This was the largest combined force raised by the Creek during the entire war.[32] On January 29, the Redsticks launched an attack on the American camp at dawn. After daylight, Floyd's army repulsed the attack. Casualty figures vary for Floyd's force, from 17 to 22 killed, and 132 to 147 wounded. Floyd estimated Red Stick casualties as 37 killed, including Chief High-head Jim. Georgia retreated to Fort Mitchell with Floyd, who was severely wounded in the leg. The "Battle of Calebee Creek" was Georgia's last offensive operation of the war.[33]

Mississippi militia

In October, General Thomas Flourney organized a force of about 1,000—consisting of the Third United States Infantry, militia, volunteers, and Choctaw Indians—at Fort Stoddert. General Claiborne, ordered to lay waste to Creek property near the junction of Alabama and Tombigbee, advanced from Fort St. Stephen. He achieved some destruction but no military engagement.[34][35] At roughly the same time, Captain Sam Dale left Fort Madison (near Suggsville) going southward to the Alabama River. On November 12 a small party rowed out to intercept a war canoe. Dale wound up alone in the canoe in hand-to-hand combat with four warriors.[36]

Continuing to a point about 85 miles (140 km) north of Fort Stoddert, Claiborne established Fort Claiborne. On December 23, he encountered a small force at the Holy Ground and burned 260 houses. William Weatherford was nearly captured during this engagement. Casualties for the Mississippian's were 1 killed and 6 wounded. 30 Creek soldiers were killed in the engagement, however. Because of supply shortages, Claiborne withdrew to Fort St. Stephens.[37]

North Carolina and South Carolina militia

Brigadier General Joseph Graham's brigade of troops from North and South Carolina (included Colonel Nash's South Carolina militia) deployed along the Georgia frontier to deal with the Red Sticks. Colonel Reuben Nash's South Carolina regiment of volunteer militia traveled from South Carolina at the end of January 1814. The militia marched to the start of the Federal Road in Augusta, Georgia, walking to Fort Benjamin Hawkins (in modern Macon, Georgia) en route to reinforce the various forts including Fort Mitchell, Alabama (in modern Phenix City, Alabama).[38] Other companies in the Nash's regiment were at Fort Mitchell by July 1814. Graham's brigade participated in only a few skirmishes before returning home.

Tennessee campaign

Although Jackson's mission was to defeat the Creek, his larger objective was to move on Pensacola. Jackson's plan was to move south, build roads, destroy Upper Creek towns and then later proceed to Mobile to stage an attack on Spanish held Pensacola. He had two problems: logistics and short enlistments. When Jackson began his advance, the Tennessee River was low, making it difficult to move supplies, and there was little forage for his horses.[39]

On October 10, Jackson along with 2,500 troops, set out on the expedition, his arm in a sling. Jackson established Fort Strother as a supply base. On November 3, his top cavalry officer, Brigadier General John Coffee, defeated a band of Red Sticks at the Battle of Tallushatchee. It was a brutal battle, and many Red Sticks, including some women and children, were killed.[40] After this, Jackson received a call for help from 150 allied Creeks besieged by 700 Red Stick warriors. Jackson marched his troops to relieve the siege, and won another decisive victory at the Battle of Talladega on November 9.[41]

After Talladega, however, Jackson was plagued by supply shortages and discipline problems arising from his men's short term enlistments. Cocke, with East Tennessee Militia, took the field on October 12. His route of march was from Knoxville to Chattanooga and then along the Coosa toward Fort Strother. Because of rivalry between the East and West Tennessee militias, Cocke was in no hurry to join Jackson, particularly after he angered Jackson by mistakenly attacking a friendly village on November 17. When he finally reached Fort Strother on December 12, the East Tennessee men only had 10 days remaining on their enlistments. Jackson had no choice but to dismiss them.[42][43] Furthermore, General Coffee, who had returned to Tennessee for remounts, wrote Jackson that the cavalry had deserted. By the end of 1813, Jackson was down to a single regiment whose enlistments were due to expire in mid-January.

Although Governor Blount had ordered a new levee of 2,500 troops, Jackson would not be up to full strength until the end of February. When a draft of 900 raw recruits arrived unexpectedly on January 14, Jackson was down to a cadre of 103 and Coffee, who had been "abandoned by his men".[44][45][46]

Since new men had enlistment contracts of only sixty days, Jackson decided to get the most out of his untried force. He departed Fort Strother on January 17 and marched toward the village of Emuckfaw to cooperate with the Georgia Militia. However, this was a risky decision. It was a long march through difficult terrain against a numerically superior force, the men were inexperienced, undisciplined, and insubordinate, and a defeat would have prolonged the war. After two indecisive battles at Emuckfaw and Enotachopo Creek, Jackson returned to Fort Strother and did not resume the offensive until mid-March.[47]

The arrival of the 39th United States Infantry on February 6, 1814, provided Jackson a disciplined core for his force, which ultimately grew to about 5,000 men. After Governor Blount ordered the second draft of Tennessee militia, Cocke, with a force of 2,000 six-month men, once again marched from Knoxville to Fort Strother. Cocke's men mutinied when they learned that Jackson's men only had three-month enlistments. Cocke tried to pacify his men, but Jackson misunderstood the situation and ordered Cocke's arrest as an instigator. The East Tennessee militia reported to Fort Strother without further comment on their term of service. Cocke was later cleared.[48]

Jackson spent the next month building roads and training his force. In mid March, he moved against the Red Stick force concentrated on the Tallapoosa at Tohopeka (Horseshoe Bend). He first moved south along the Coosa, about half the distance to the Creek position, and established a new outpost at Fort Williams. Leaving another garrison there, he then moved on Tohopeka with a force of about 3,000 effective fighting men augmented by 600 Cherokee and Lower Creek allies. The Battle of Horseshoe Bend, which occurred on March 27, was a decisive victory for Jackson, effectively ending the Red Stick resistance.[49]

Results

On August 9, 1814, Andrew Jackson forced headmen of both the Upper and Lower Towns of Creek to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson. Despite protest of the Creek chiefs who had fought alongside Jackson, the Creek Nation ceded 21,086,793 acres (85,335 km²) of land—approximately half of present-day Alabama and part of southern Georgia—to the United States government. Even though the Creek War was largely a civil war among the Creek, Andrew Jackson recognized no difference between his Lower Creek allies and the Red Sticks who fought against him. He took the lands of both for what he considered the security needs of the United States.[1] Jackson forced the Creek to cede 1.9 million acres (7,700 km²) that was also claimed as hunting grounds of the Cherokee Nation, who had fought as U.S. allies during the Creek War as well.[50]

With the Red Sticks subdued, Jackson turned his focus on the Gulf Coast region in the War of 1812. On his own initiative, he invaded Spanish Florida and drove a British force out of Pensacola.[51] He defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815. In 1818, Jackson again invaded Florida, where some of the Red Stick leaders had fled, an event known as the First Seminole War.

As a result of these victories, Jackson became a national figure and eventually became the seventh President of the United States in 1829. As president, Andrew Jackson advocated the Indian Removal Act, passed by congress in 1830, which authorized negotiation of treaties for exchange of land and payment of annuities, and authorized removal of the Southeastern tribes to the Indian Territory, west of the Mississippi River.

See also

- Indian Campaign Medal

- List of Indian massacres

- George Mayfield, interpreter and spy for Andrew Jackson, later honored by the Creek for his integrity during treaty negotiations

References

- Green (1998), Politics of Removal, p. 43

- Waselkov, 4-5.

- Braund, Deerskins and Duffels.

- Owsley, 18-24.

- Thrower. "Casualties and Consequences of the Creek Civil War." in Rethinking Tohopeka, 12.

- Braund, 178.

- Michael D. Green, The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1985, pp. 38-39, accessed 11 September 2011

- Waselkov, 73.

- Braund, Deerskins and Duffels, 58.

- Owsley, 11-13.

- Owsley, 14-15.

- Green (1985), Politics of Removal, pp. 40-42

- Braund, "Red Sticks". Rethinking Tohopeka. 89-93.

- Ehle 104-105

- Owsley, 52.

- Adams pp. 777-778

- Ehle p. 104-105

- Wilentz 2005, pp. 23-25.

- Mahon, 232-233

- Mahon p. 234

- Remini, p. 72

- Remini p. 72, Adams p.787

- Adams, pp. 782-785

- Mahon p. 235

- Mahon p. 235

- Adams p. 783

- Wasselkov, 159-161.

- Hawkins to Floyd, September 30, 1813, in Grant, Letters, Journals, and Writings of Benjamin Hawkins, Vol. Two 1802–1816, Beehive Press, 1980. 668-69.

- Owsley, 51.

- Owsley, 53.

- Mahon p. 240, Adams p. 788-789

- Waselkov, 168.

- Adams 793-794, Mahon 242, the second casualty estimates are Mahon's

- Mahon 239

- Adams 789

- Mahon 239

- Mahon 240

- Note: Company muster rolls of Captain John Wallace (one of Nash's companies) list the company near Fort Hawkins on Feb. 9, near Fort Jackson (Alabama) on May 13, and near Fort Hawkins on July 13.

- Mahon p. 236, Adams p.784

- Remini 1977, pp. 192-193.

- Wilentz 2005, pp. 25-28.

- Adams p. 787

- Mahon p. 238-239

- Adams, p. 791

- Adams p. 791

- Mahon pp. 237-239

- Adams pp. 791-793

- Adams p. 798

- Adams 795-796

- Ehle 123

- Mahon, p. 350

Sources

- Braund, Kathryn E. ed., Tohopeka: Rethinking the Creek War and the War of 1812. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2012.

- Adams, Henry, History of the United States of America During the Administrations of James Madison (1889)

- Andrew Burstein The Passions of Andrew Jackson (Alfred A. Kopf 2003), p. 106 ISBN 0-375-41428-2

- Holland, James W. "Andrew Jackson and the Creek War: Victory at the Horseshoe Bend", Alabama Review, 1968 21(4): 243–275.

- Kanon, Thomas. "'A Slow, Laborious Slaughter': The Battle Of Horseshoe Bend." Tennessee Historical Quarterly, 1999 58(1): 2–15.

- Lossing, Benson J. (1869). "XXXIV: War Against the Creek Indians.". Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. New York: Harper & Brothers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) useful for illustrations

- Mahon, John K., The War of 1812, (University of Florida Press 1972) ISBN 0-8130-0318-0

- Remini, Robert V. (1977). Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 1767–1821. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-8018-5912-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waselkov, Gregory A. A Conquering Spirit: Fort Mims and the Redstick War of 1813–1814. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2006.

- Wilentz, Sean (2005). Andrew Jackson. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-6925-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Richard D. Blackmon. The Creek War, 1813-1814. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 2014.

- Mike Bunn and Clay Williams. Battle for the Southern Frontier: The Creek War and the War of 1812. The History Press, 2008.

- Kathryn E. Holland Braund. Deerskins and Duffels: The Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685–1815. University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

- Benjamin W. Griffith Jr. McIntosh and Weatherford: Creek Indian Leaders. University of Alabama Press, 1998.

- Angela Pulley Hudson. Creek Paths and Federal Roads: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves and the Making of the American South. University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Roger L. Nichols. Warrior Nations: The United States and Indian Peoples. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.

- Frank L. Owsley Jr. Struggle for the Gulf Borderlands: The Creek War and the Battle of New Orleans, 1812–1815. University of Alabama Press, 2000.

- Claudio Saunt. A New Order of Things: Property, Power, and the Transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733–1816. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Gregory A. Waselkov. A Conquering Spirit: Fort Mims and the Redstick War of 1813–1814. University of Alabama Press, 2006.

- J. Leitch Wright Jr. Creeks and Seminoles: The Destruction and Regeneration of the Muscogulge People. University of Nebraska Press, 1990.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Creek War. |

- "The Creek War 1813-1814", Horseshoe Bend National Military Park, National Park Service

- A map of Creek War Battle Sites from the PCL Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

- The War of 1812