Northwest Indian War

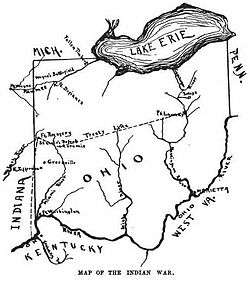

The Northwest Indian War (1785–1795), also known as the Ohio War, Little Turtle's War, and by other names, was a war between the United States and a confederation of numerous Native American tribes, with support from the British, for control of the Northwest Territory. It followed centuries of conflict over this territory, first among Native American tribes, and then with the added shifting alliances among the tribes and the European powers of France and Great Britain, and their colonials. The United States Army considers it their first of the United States Indian Wars.[1]

| Northwest Indian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||||

This depiction of the Treaty of Greenville negotiations may have been painted by one of Anthony Wayne's officers. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Western Confederacy | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

Blue Jacket Little Turtle Buckongahelas Egushawa | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

1,221 killed 458 wounded |

1,000+ killed Unknown wounded | ||||||||

Article 2 of the Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the American Revolutionary War, used the Great Lakes as a border between British territory and that of the United States. Numerous Native American peoples inhabited this region, known to the United States as the Ohio Country and the Illinois Country. Despite the treaty, the British kept forts there and continued policies that supported the Native Americans. With the encroachment of European settlers west of the Appalachians after the War, a Huron-led confederacy formed in 1785 to resist usurpation of Indian lands, declaring that lands north and west of the Ohio River were Indian territory. President George Washington directed the United States Army to enforce U.S. sovereignty over the territory. The U.S. Army, consisting mostly of untrained recruits and volunteer militiamen, suffered a series of major defeats, including the Harmar Campaign (1790) and St. Clair's Defeat (1791). About 1,000 soldiers and militiamen were killed and the United States forces suffered many more casualties than their opponents. These defeats are among the worst ever suffered in the history of the US Army.

After St. Clair's disaster, Washington ordered Revolutionary War hero General "Mad" Anthony Wayne to organize and train a proper fighting force. Wayne took command of the new Legion of the United States late in 1792. After a methodical campaign up the Great Miami and Maumee river valleys in western Ohio Country, he led his men to a decisive victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers near the southwestern shore of Lake Erie (close to modern Toledo, Ohio) in 1794. Afterward he went on to establish Fort Wayne at the Miami capital of Kekionga, the symbol of U.S. sovereignty in the heart of Indian Country. The defeated tribes were forced to cede extensive territory, including much of present-day Ohio, in the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. The Jay Treaty in the same year arranged for cessions of British Great Lakes outposts on the U.S. territory.

Background

Control of the area south of the Great Lakes and north of the Ohio River was contested for centuries. European influence first began when the Dutch and English supported the Iroquois in the 17th century Beaver Wars.[2] In the 18th century, the region became a focal point for colonial wars between France and Great Britain, especially in the Ohio Country. The French and Indian War initiated when France and Virginia disputed control of the area,[3] and the different Native nations in the region supported their favored trade partners (French or British) or remained neutral. In the Treaty of Paris (1763), France ceded control of the region to the British, although many French colonials remained and Native nations resisted the arrival of British control in Pontiac's War.[4] Eager to avoid a new conflict, the British government issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix in an attempt to fix the boundary between Virginia, Pennsylvania, and native lands.[5] However, this created discontent among the British colonials who wanted to settle in the region, and was one of the early causes eventually leading to Lord Dunmore's War[6] and the American Revolutionary War.[4][7]

As the Revolution approached, tensions grew in the Ohio Valley. The Grand Ohio Company was built on speculation in Native American lands,[8]:194 and Great Britain granted tracts of Native land to veterans of the French and Indian War to pay off debts.[8]:201 But in 1772, Great Britain redeployed many of its western forces to the East Coast to suppress the growing rebellion, removing a deterrent to illegal squatters.[8]:206 In 1774, Great Britain determined that these land grants could not be granted to colonial veterans, meaning that colonial veterans who had invested heavily in land speculation (such as George Washington) would lose their investment.[8]:211 That same year, the Quebec Act placed the lands between the Ohio River and Great Lakes under the jurisdiction of Quebec.[8]:211 That Spring, a group of settlers led by Daniel Greathouse committed the Yellow Creek massacre, in which thirteen women and children were killed, including the wife and pregnant sister of Tachnechdorus, who had been friendly to settlers until that time. In a particularly brutal act, Koonay, the sister of Tachnechdorus, was strung up by the wrists while her unborn baby was impaled. As expected, Tachnechdorus took revenge, and was supported by the Shawnee, who expressed discontent that they had still not been paid for their lands.[8]:208 Still other Shawnee fled the Scioto River valley, avoiding the anticipated war with the white settlers who suddenly surrounded them.[8]:207

During the course of the American Revolutionary War, United States forces captured outposts in the lower areas of the territory, but British forces maintained control of Fort Lernoult (Detroit).[9] In September 1778, the United States negotiated the Treaty of Fort Pitt and secured Delaware support for an attack on Detroit the following month. The campaign was abandoned after the death of Lenape leader White Eyes.[10] Additional actions in the Western theater of the American Revolutionary War further damaged relations between the United States and many of the region's native inhabitants. In 1780, British and Native American forces swept across the Midwest to clear the territories of rebels and Spanish forces, attacking St. Louis and Cahokia and Kentucky, but were repulsed in both battles. Within months, General George Rogers Clark retaliated by crossing the Ohio River and attacking Shawnee towns Chillicothe and Piqua.[6] That same year, French officer Augustin de La Balme led a militia force towards Fort Detroit, stopping to sack Kekionga along the way. The Miami tribes, which had been divided in their allegiances during the Revolution, now joined against the United States, and the retaliation against La Balme's militia launched the military career of an obscure Miami warrior named Mihšihkinaahkwa, known as Little Turtle.[11]:88–89 The following year, British and Native American forces attacked Fort Laurens, a U.S. fort in the Ohio Territory.[12]

Two of the last battles of the Revolutionary War include the 1782 Siege of Fort Henry and Battle of Blue Licks, both attacks by British and Native Americans on settlers across the Ohio River in Virginia and Kentucky. The same year saw the Gnadenhutten massacre[13] and Crawford expedition, which further increased distrust between Native Americans and the United States.[14] The western theater had a markedly different tone than the European style battles in the east, which left a generational impact on US settlers and Native Nations.[Note 1]

In the Treaty of Paris (1783), Great Britain ceded control of the region, but the native nations were not party to these negotiations,[8]:283 and the new United States was no longer bound by British treaties with native nations.[15] BG Allan Maclean at Fort Niagara reported that the native nations could neither believe that the king would give their land to the United States, nor that the United States would accept them.[8]:283 Many preferred to trade with the British rather than the young United States, and British agents continued to operate in the western region and influence the residents. The Iroquois and the western tribes met on the Sandusky Bay in the same year and, after listening to the pan-Indian ideals of Joseph Brant and Alexander McKee, pledged that no one would concede land to the United States without permission of the entire association.[11]:89–91 Fighting in the west did not end with the treaty, however. 40 Pennsylvanians and Virginians were killed by Native Americans in Spring 1784, and conflicts continued in Kentucky.[16]

The newly independent United States was financially fragile; it needed peace to reduce military expenses, but also wanted to pay off debts by selling lands the British had ceded,[8]:283 as the British had done after the French & Indian War. In 1784 the U.S. negotiated the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1784), in which the Iroquois negotiators ceded control of western regions.[17] The Iroquois nations refused to ratify the treaty, however, because it gave away too much land, and the Western Confederacy refused to recognize any right of the Iroquois to give away control of lands which the Iroquois did not occupy. In the following year, the Treaty of Fort McIntosh attempted to open most of the Ohio Country to American settlement. This united the tribes of the Western Confederacy in opposition to American encroachment on their territories.[18]

Formation of the confederacy

Co-operation among the Native American tribes in the Western Confederacy had gone back to the French colonial era. It was renewed during the American Revolutionary War. At gatherings in 1783 and 1784, native nations worked to formalize a union to defend against the United States.[19]:22 The confederacy formally came together in Autumn 1785 at Fort Detroit, proclaiming that the parties to the confederacy would deal jointly with the United States, forbidding individual tribes from dealing directly with the United States, and declaring the Ohio River as the boundary between their lands and those of American settlers.[20] Nevertheless, a group of Shawnee, Delaware, and Wyandot agreed to allow U.S. settlement in a tract of land north of the Ohio River in the January 1786 Treaty of Fort Finney.[21] This treaty sparked an eruption of violence between native inhabitants and U.S. settlers.[11]:101–102 That year, a Wyandot messenger named Scotosh warned Congress that the Wabash, Twightwee, and Miami nations would disrupt U.S. surveyors, and Congress promised reprisals if that occurred.[22] The Ft. Finney treaty was rejected by a September 1786 council of 35 native nations, including British representatives, who met at a Wyandot (Huron) village on the Upper Sandusky.[19]:46–47 Logan's Raid into Shawnee territory occurred weeks later, hardening Native views on U.S. relations. That December, a council on the Detroit River sent a letter to U.S. Congress signed by eleven native nations, who referred to themselves as "the United Indian Nations, at their Confederate Council."[19]:58–59[23]

In July 1787, Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, formally organizing the entire Northwest Territory under United States control, and prohibited the taking of Indian lands "without their consent."[24] Months later, in October 1787, Congress responded to the United Indian Nations' letter by directing the governor of the new Northwest Territory, General Arthur St. Clair, to "re-establish peace and harmony" with native nations.[19]:62 Congress took no further action in 1787, because it was engrossed in the debate over the proposed US Constitution.[19]:62 The confederacy assembled on the Maumee River in Autumn 1787 to consider a U.S. reply, but as they had not yet received one, they adjourned.

Arthur St. Clair did not arrive in the territory until Summer 1788, when he invited American Indian nations to a council at Fort Harmar that Autumn, in order to negotiate terms by which the United States could purchase lands from them and avoid war.[25] The sight of Fort Harmar and nearby Marietta North of the Ohio River convinced some that negotiations with the United States were necessary. At pre-negotiation meetings, Joseph Brant offered a compromise to other Native American leaders: to allow existing US settlements north of the Ohio River and draw a new boundary at the mouth of the Muskingum River.[11]:108–110 Other leaders were infuriated by US incursions across the Ohio, and rejected Brant's compromise. A Wyandot delegation offered a belt of peace to the Miami delegation, but they refused to accept it. One of the Wyandot then placed it on Little Turtle's shoulder, but the Miami leader shrugged it off to the ground.[11]:112 Brant then sent St. Clair a letter asking that treaty negotiations be held at a different location; St. Clair refused, and accused Brant of acting for the British. At this, Brant determined to boycott negotiations with the United States, and suggested others do the same. About 200 moderate American Indians came to Fort Harmar in December, and agreed to concessions in the 1789 Treaty of Fort Harmar, which moved the border and named the United States as sovereign over native lands.[11]:112–113 To those who had refused to attend or sign, the treaty re-enforced the United States' appetite for native lands in the region without addressing the concerns of the native nations.

The confederacy was a loose association of primarily Algonquin-speaking tribes in the Great Lakes area. The Wyandot (Huron) were the nominal "fathers," or senior guaranteeing tribe of the confederacy, but the Shawnee and Miami provided the greatest share of the fighting forces. Other tribes in the confederacy included the Delaware (Lenape), Council of Three Fires (Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi), Kickapoo, Kaskaskia, and Wabash Confederacy (Wea, Piankashaw, and others).[26] In most cases, an entire tribe was not involved in the war; the Indian societies were generally not centralized. Villages and individual warriors and chiefs decided on participation in the war. Nearly 200 Cherokee warriors from two bands of the Overmountain Towns fought alongside the Shawnee from the inception of the Revolution through the years of the Indian Confederacy. In addition, the Chickamauga (Lower Town) Cherokee leader, Dragging Canoe, sent a contingent of warriors for a specific action.

Some warriors of the Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes from the southeast, which had been traditional enemies of the northwest tribes, served as scouts for the United States during these years.

British influence

Still opposed to the US, some British agents in the region sold weapons and ammunition to the Indians and encouraged attacks on American settlers. Alexander McKee, a British agent born to a Shawnee mother, was a central figure in the confederacy. He worked to unite the diverse nations and bands of Native Americans in the region, but also represented the interests of Great Britain.[27]

British Lieutenant Governor John Simcoe, a veteran of the American Revolutionary War, was delighted with the United States' failures, and hoped for British involvement in the creation of a neutral barrier state between the United States and Canada.[28]:229[29] In 1793, however, Simcoe abruptly changed policy and sought peace with the United States in order to avoid opening a new front in the French Revolutionary Wars.[28]:231 Simcoe treated the United States commissioners – Benjamin Lincoln, Beverly Randolph, and Timothy Pickering – cordially when they arrived at Niagara in May 1793,[28]:238–40 seeking an escort by way of the Great Lakes in order to avoid the fate of John Hardin and Alexander Truman in 1792.[30]:105

Course of the war

Logan's raid

War parties launched a series of isolated raids in the mid-1780s, resulting in escalating bloodshed and mistrust. In April 1786, a militia from Vincennes attacked a village on the Embarras River, forcing Piankeshaw to move farther away and consolidate near the Vermilion River. Over 400 Piankeshaw and Wea returned with a war party in July, but were persuaded not to attack Vincennes. That Autumn, Generals George Rogers Clark and Benjamin Logan led a two-pronged force of Kentucky militia in punitive raids against Native American villages to the north of the Ohio River.[28]:35–36 Clark's force, considered the primary expedition, set off in September and marched north along the Wabash River to Illinois country. He was hindered by logistical problems caused by low water on the river, and when he reached the mouth of the Vermilion River in October, he was beset by mutiny and mass desertion. Clark returned with the remains of his force to Vincennes, his reputation in ruins.[28]:37

General Logan, meanwhile, recruited and trained for his secondary force of Federal soldiers and mounted Kentucky militia against several Shawnee towns along the Mad River. The Shawnee nation was divided in their response to the United States settlers, but the Kentucky settlers made no distinction between hostile and friendly villages.[28]:36 The Shawnee villages along the Mad River were defended primarily by noncombatants while the warriors were hunting or raiding forts in Kentucky. Logan burned the native towns and food supplies, and killed or captured numerous natives. Against Logan's orders, Captain Hugh McGary murdered an elderly Shawnee chief named Moluntha, who was considered friendly towards the United States and who had even hoisted a striped flag to welcome Logan's men.[28]:38–39 Logan continued to 7 other villages, killing, torturing, or capturing dozens of villagers, including women and children. The militia also plundered their goods and burned their crops before returning to Kentucky.[28]:40-41 Logan's raid devastated the Shawnee nation, who's survivors struggled that winter due to the destroyed harvests, but it also united the Shawnee against the United States. Reports of Logan's raid alarmed the confederate council in Detroit that November, and Shawnee raids into Kentucky were reported by December 1786.[28]:41–42

Native American raids on both sides of the Ohio River resulted in increasing casualties. During the mid- and late-1780s, American settlers south of the Ohio River in Kentucky and travelers on and north of the Ohio River suffered approximately 1,500 casualties. Settlers retaliated with attacks on Indians. In 1789, the new United States Secretary of War Henry Knox argued that Congress had provoked Native Americans by claiming possession of their territories.[31]

Harmar Campaign

In 1790, the new President of the United States George Washington and Secretary of War Henry Knox ordered General Josiah Harmar to launch the Harmar campaign, a major western offensive into the Shawnee and Miami country. General Harmar's ultimate goal was Kekionga, a large Native American city that was important to the British trade economy,[32]:17 and that protected a strategic portage between the Great Lakes Basin and Mississippi watershed. Washington, as early as 1784, had told Henry Knox that a strong U.S. post should be established at Kekionga. Knox, however, was concerned that a U.S. fort at Kekionga would provoke the Indians and denied St. Clair's request to build a fort there. St. Clair, in 1790, had told both Washington and Knox that "we will never have peace with the Western Nations until we have a garrison there."[32]:21-3 Western native leaders, meanwhile, met at Kekionga to determine a response to the Treaty of Fort Harmar.

General Harmar's forces of about 1,453 militia and regulars departed Fort Washington on 7 October 1790. From 19–21 October 1790, General Harmar lost 3 successive skirmishes near Kekionga (present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana). On 19 October, a scouting party of about 400 mixed forces under the command of Colonel John Hardin was lured into an ambush near the village of Le Gris, losing 129 soldiers in one of two defeats that has been called Hardin's Defeat.[33][34] The following day, another scouting party under Ensign Phillip Hartshorn was ambushed, but Harmar did not move to assist them or recover their remains. Finally, on 21 October 1790, a mixed party of militia and regulars under Colonel Hardin established attack positions on Kekionga and awaited reinforcements from General Harmar, which never came. Instead, forces under Little Turtle overwhelmed Hardin and compelled the U.S. forces to retreat in the second battle known as Harmar's Defeat. With 3 consecutive losses, more than 300 casualties, and low morale, Harmar retreated to Fort Washington. Following Harmar's defeat, Knox changed his mind, instructing St. Clair to fortify Kekionga the following year.[32]:21-3

Because they were both present when Harmar's army arrived, this was the first full military operation shared between Miami leader Little Turtle and Shawnee leader Blue Jacket.[11]:113–115 It was largest the Native American victory over US forces until the following year,[35] and emboldened Native Nations within the Northwest Territory. The following January, Indian forces attacked settlements at the Big Bottom massacre and the Siege of Dunlap's Station.[36]:15

St. Clair's defeat

Washington ordered Major General Arthur St. Clair, who had been president of Congress when the Northwest Ordinance passed and was now serving as governor of the Northwest Territory, to mount a more vigorous effort by Summer 1791 and build a series of forts along the Maumee River. The hastily assembled expeditionary force had considerable troubles finding adequate supplies, receiving undamaged materials from Philadelphia, and finding skilled tradesmen.[38] After assembling men and supplies, St. Clair was somewhat ready, but the troops had received little training. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson led raids along the Wabash River, intending to create a distraction that would aid St. Clair's march north. In the Battle of Kenapacomaqua, Wilkinson killed 9 Wea and Miami, and captured 34 Miami as prisoners, including a daughter of Miami war chief Little Turtle.[39] Many of the confederation leaders were considering terms of peace to present to the United States, but when they received news of Wilkinson's raid, they readied for war.[28]:159 Wilkinson's raid thus had the opposite effect, uniting the tribes against St. Clair instead of distracting them.

Faced with a shortage of food and expiring levies,[38] St. Clair's army of 1,486 and 200 camp followers finally departed Fort Washington in October 1791, by which time the confederation had time to prepare. St. Clair stopped to erect Fort Jefferson as a supply depot,[40] and continued North towards Kekionga, but the army and followers had dwindled to a combined mass of 1,120 by November. At dawn on 4 November 1791, St. Clair's force was camped (near modern Fort Recovery, Ohio) with weak defenses set up on the perimeter. A Native American force of about 2,000 warriors, led by Little Turtle and Blue Jacket, struck quickly. Surprising the Americans, they soon overran the poorly prepared perimeter. The barely trained recruits panicked and were slaughtered, along with many of their officers, who frantically tried to restore order and stop the rout. After 4 hours, St. Clair ordered an evacuation, abandoning the wounded.[41] The small Fort Jefferson could not protect the retreating forces, and they were forced to continue all the way to Fort Washington for safety. The U.S. casualty rate was 69%, based on the deaths of 632 of the 920 soldiers and officers, with 264 wounded. Nearly all of the 200 unarmed camp followers were killed, for a total of about 832 deaths—the highest United States losses in any of its battles with Native Americans.[42] [43] St. Clair and his aide-de-camp were among the wounded. With a casualty rate of 97%, St. Clair's Defeat remains one of the worst disasters in U.S. Army history.[44]

The American Indian coalition did not immediately follow up on their victory. Instead, most returned to their villages to hunt before Winter set in.[28]:196 Kekionga was short on supplies because of the war, so they moved most of the inhabitants to the Auglaize River.[11]:143–144 This removed them from the target of repeated military campaigns, but as Thomas McKee argued, also put them closer to the trade and military support offered by the British at Detroit. The various leaders agreed to a grand council the following year.

The British conceived plans to re-negotiate control of the NorthWest Territory with the United States, but opted instead to curry favor with the young republic due to escalating tensions with France. The US response was markedly different. Within weeks of learning of the disaster, President Washington declared the US to be "involved in actual war!"[28]:203–205 and urged Congress to raise an army capable of conducting a successful offense against the Western Confederacy. Congress responded by establishing the Legion of the United States and increasing military pay.[45] It also passed the Militia Acts of 1792.[46] Washington forced St. Clair to resign, replacing him with Major General Anthony Wayne.

Fort Jefferson

In January 1792, Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson assumed command of the Second Regiment United States Army at Fort Washington,[30]:9 and constructed Fort St. Clair to improve communications and logistics between Fort Hamilton and Fort Jefferson.[28]:218 The three forts were garrisoned with less than 150 men each, including infirmed soldiers and servants.[30]:13 On 11 June 1792, a force of about 15 Shawnee and Delaware attacked the northern-most outpost, Fort Jefferson, while the detachment there was cutting hay. Four soldiers were killed and left in the hay and 15 were captured. Eleven of the captives, including the sergeant in charge, were later killed, and the four remaining soldiers were sent to a Chippewa village.[28]:219 On 29 September, several soldiers were killed while guarding cattle at Fort Jefferson.[28]:219

Council on the Auglaize

Stinging from St. Clair's defeat and hoping to avoid another campaign, George Washington asked Joseph Brant to facilitate peace negotiations.[36]:10 After the discovery of United States espionage operations,[28]:211-12 Washington sent out peace emissaries. The first was Major Alexander Truman,[47] his servant William Lynch and guide/interpreter William Smalley. Truman and Lynch were killed; Truman was apparently killed prior to 20 April 1792 at what later became Ottawa, Putnam County, Ohio.[48] A similar mission in May 1792 under Colonel John Hardin also ended in Hardin and his servant Freeman being mistaken for spies and killed on the site of modern Hardin, Ohio.

In June 1792, Native Americans and Kentucky settlers met for a prisoner exchange at Vincennes. William Wells, who fought with the confederacy at St. Clair's defeat, came to claim his wife Sweet Breeze, the daughter of Little Turtle. At Vincennes he met CPT Samuel Wells, his brother who had fought with the United States at St. Clair's defeat. William returned to Kentucky with his brother.[36]:10 That September, a U.S. delegation led by Rufus Putnam and John Hamtramck, and with assistance William Wells,[36]:10 returned to Vincennes and negotiated a treaty with the tribes of the lower Wabash River. The treaty and the Wabash tribes were celebrated in Philadelphia, and Henry Knox suggested that the confederacy had been weakened by 800 warriors. The U.S. senate would not consider the treaty for another 2 years, however, at which point it failed to ratify it.[11]:256, 262

Meanwhile, Native American tribes continued to debate whether to continue the war or sue for peace while they had the advantage. A Grand Council of several nations met at the confluence of the Auglaize and Maumee Rivers in Sept. 1792.[28]:223 Alexander McKee represented British interests and arrived in late September. For a week in October, pro-war factions, especially Simon Girty, the Shawnee, and Miami, debated moderate factions, especially the Six Nations represented by Cornplanter and Red Jacket.[28]:226-7 The Council agreed that the Ohio River must remain the boundary of the United States, that the forts in the Ohio Country must be destroyed, and that they would meet with the United States at the Lower Sandusky River in spring 1793.[28]:227 The United States received the demands of the Grand Council with indignation, but Henry Knox agreed to send treaty commissioners Benjamin Lincoln, Timothy Pickering, and Beverley Randolph to the 1793 council[49] and suspend all offensive operations until that time.[28]:228

Raid on Camp St. Clair

Following the decision of the Grand Council, Little Turtle gathered a force of 200 Miami and Shawnee from Auglaize past Fort Jefferson and Fort St. Clair,[11]:264-266 and reached Fort Hamilton on 3 November in time to attack close to the United States settlements on the anniversary of St. Clair's Defeat. They captured two prisoners and learned that a large convoy of packhorses had left for Fort Jefferson and was due back in a matter of days. Little Turtle moved north and found the convoy, nearly 100 horses and 100 Kentucky militia led by Major John Adair and Lieutenant George Madison,[36]:11 camped just outside Fort St. Clair.[28]:220 Little Turtle attacked at dawn, just as Major Adair recalled his sentries. The militia conducted an organized retreat to the fort, losing six killed and four missing, while another five were wounded. Little Turtle's forces lost two warriors, but did not pursue the militia forces. The United States claimed victory since they maintained control of the fort, but Little Turtle had accomplished his goal.[36]:11 The Native American forces had captured the fort's provisions in order disrupt US supply lines and make the string of forts more costly to secure.[11]:264–266 All horses were killed, wounded, or driven off; only 23 were later recovered.[11]:265 Major Adair later criticized Fort St. Clair's commandant, Captain Bradley, for his failure to come to their aid.[30]:86 Wilkinson considered the horses to be a loss that would make the advanced forts un-defendable,[28]:221 and he blamed newly appointed General Anthony Wayne, writing to Secretary Knox that Wayne had ordered officers to engage "in defensive measures only."[11]:266

Sandusky River council

The 1793 Sandusky River council was delayed until late in July. The United States commissioners – Benjamin Lincoln, Beverly Randolph, and Timothy Pickering – arrived at Niagara in May 1793,[28]:238–40 seeking a British escort by way of the Great Lakes in order to avoid the fate of John Hardin and Alexander Truman in 1792.[30]:105 At the council, disagreement broke out between Shawnee and the Six Nations. The Shawnee and Delaware insisted that the United States recognize the 1768 Fort Stanwix Treaty between the Six Nations and Great Britain, which set the Ohio River as a boundary. Joseph Brant countered that the Six Nations had nothing to gain from this demand and refused to concede. The U.S. commissioners argued that it would be too expensive to move white settlers who had already established homesteads north of the Ohio River.[28]:240-45 On 13 August, the Council (without the Six Nations) sent a declaration to the U.S. commissioners, contesting U.S. claims to any lands above the Ohio since they were based on treaties made with nations that did not live there, and with money that had no value to the Native tribes.[50] The council proposed that the U.S. relocate white settlers using the money that would have been used to buy Ohio lands and pay the Legion of the United States.[28]:246 The council ended with discord among the confederacy, and Benjamin Lincoln wrote to John Adams that they had failed to secure a peace in the Northwest.[51]

On 11 September 1793, William Wells arrived at Fort Jefferson with news of the Grand Council's failure, and with a warning that a force of over 1500 warriors was ready to attack Fort Jefferson and the Legion of the United States.[30]:149–50

Legion of the United States

After St Clair's disaster, Washington had ordered General "Mad" Anthony Wayne to build a well-trained force while peace negotiations took place with the confederacy.[52] Wayne accepted the appointment in 1792 and took command of the new Legion of the United States later that year, taking time to train and supply the new Army while the United States negotiated terms of peace. General Wilkinson was disappointed that he was not given command of the Legion, and as Wayne's 2nd in command, secretly conspired to organize other officers against Wayne.[53]:250–252 In the spring of 1793, Wayne moved the Legion from Pennsylvania downriver to Fort Washington, at a camp Wayne named Hobson's Choice because they had no other options.[30]:109-110 They conducted training there during the Sandusky River council.

Upon news of the Grand Council's failure in September, Wayne advanced his troops north into Indian held territory. In November, the Legion built a new fort north of Fort Jefferson, which Wayne named Fort Greeneville on 20 November 1793 in honor of General Nathanael Greene.[30]:173–175 The Legion wintered here, but Wayne dispatched a detachment of about 300 men on 23 December to quickly build Fort Recovery on the site of St. Clair's defeat and recover the cannons lost there in 1791.[30]:184 In January 1794, Wayne reported to Knox that 8 companies and a detachment of artillery under Major Henry Burbeck had claimed St. Clair's battleground and had already built a small fort.[53]

George White Eyes[Note 2] arrived in January 1794 to discuss terms of peace, but Wayne responded that peace must be negotiated with all the involved tribes, not just the Delaware.[53] Wayne delayed at Fort Greenville until March while he waited for a response, but the council rejected Wayne's call for peace. Buckongahelas, Blue Jacket, and Little Turtle had received word from Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester that Great Britain could be at war with the United States within the year, and felt no need to discuss terms of peace.[53]:253–254 Lord Dorchester had made those remarks in February 1794 while meeting with Iroquois representatives.[28]:258 Word spread, causing an uproar in the United States and encouraging the confederacy. Dorchester warned the United States that "taking possession of any part of the Indian Territory" would be a "direct violation of His Britannic Majesty's rights."[28]:264 That April, the British constructed Fort Miami and garrisoned it with 120 soldiers with the 24th Regiment and a detachment of artillery with 8 cannon, as a defense against anticipated attacks from the United States.[28]:261–2 The United States viewed the construction of Fort Miami as a blatant act of aggression, and Wayne fumed that his Legion was not quite prepared to attack.[28]:262

By June 1794, Fort Recovery had been reinforced, and the Legion had recovered four copper cannons (two six-pound and two three-pound), two copper howitzers, and one iron carronade.[30]:234 That same month, an American Indian force of over 1,200 warriors under the nominal command of Blue Jacket, Egushawa, and the Odawa Bear Chief,[30]:241 and British officers arrived at Fort Recovery with powder and shot, intent on recovering the same cannons. The force destroyed an escort and captured or scattered several hundred pack horses used for supply convoys, but failed to capture the fort, which was defended by artillery, dragoons, and Chickasaw scouts.[30]:242–250[Note 3] The British officers recovered one cannon, but were unable to utilize it; one later stated that "had we two barrels of powder, Fort Recovery would have been in our possession with the help of St. Clair's cannon."[28]:276 Those defending the fort suffered 23 killed, 29 wounded, and three captured.[54] Estimates of the Native Nations casualties range from 17 to 50 killed, and perhaps 100 wounded, some of whom later died of their wounds.[30]:250-2 Little Turtle identified Wayne as a "black snake who never sleeps," and asked the British for artillery and soldiers, which the British declined to provide.[55]

Before departing Fort Recovery, Wayne sent a final offer of peace with two captured prisoners to the leaders of the confederation at Roche de Bout.[30]:288–289 The confederacy leaders debated a response. Little Turtle, wary of Wayne and disappointed with the British, argued that they should negotiate peace with Wayne. Blue Jacket mocked Little Turtle as a traitor and convinced the others that Wayne would be defeated, just as Harmar and St. Clair had been. Little Turtle then relinquished leadership to Blue Jacket, stating that he would only be a follower.[11]:337, 369 Three days later, on 16 August, a messenger returned with a response asking Wayne to pause at his currently location, stating "You have only to write & your Business is done, but we Indians must do all our Business with every nation of the Confederacy which takes up a great deal of time."[30]:292–293 Native American advisors told Wayne that many of the Confederation were ready to accept Wayne's offer of peace, but that Little Turtle had sent this response as a delay tactic needed to gather additional forces.[30]:292–293 Wayne departed Fort Recovery the next day. The perceived cracks in the united confederacy concerned the British, who sent reinforcements to Fort Miamis on the Maumee River.[30]:293–294

From Fort Recovery, Wayne pushed north in August 1794 and had the Legion construct Fort Adams. A tree fell on Wayne's tent at Fort Adams on 3 August 1794. He survived but was knocked unconscious. By the next day, he had recovered sufficiently to resume the march to the newly built Fort Defiance,[56] so named from a declaration by Charles Scott that "I defy the English, Indians, and all the devils of hell to take it."[57] Finally, as the Legion approached Fort Miamis, Wayne stopped to build Fort Deposit, which acted as a rally point and baggage camp so that the Legion could go into battle as light infantry.[55]

Battle of Fallen Timbers

On the morning of 20 August, the Legion broke camp and marched toward the Maumee River near modern Toledo, Ohio, where an ambush had been set by the Confederacy. This late in the campaign, the Legion was reduced to about 3,000 soldiers and militia, with many soldiers defending the supply trains and forts. Blue Jacket, the Native alliance commander, had selected a battlefield where a tornado had felled hundreds of trees, creating a natural defensive barrier.[58] Here, he placed confederation forces of about 1,500 warriors: Blue Jacket's Shawnees, Delawares led by Buckongahelas, Miamis led by Little Turtle, Wyandots led by Tarhe[59] and Roundhead, Mingos, a small detachment of Mohawks, and a British company of Canadian militiamen dressed as Native Americans under LTC William Caldwell.[28]:298

Odawa and Potawatomi under Little Otter and Egushawa occupied the center and initiated the attack against the Legion's scouts. Front elements of the Legion's columns initially collapsed under pursuing Native Americans. Wayne immediately committed his reserves to the center to halt their advance, and divided his infantry into two wings, the right commanded by James Wilkinson, the other by Jean François Hamtramck. The Legion's cavalry secured the right along the Maumee River. General Scott provided a brigade of mounted militia to guard the open left flank, while the rest of the Kentucky militia formed a reserve.[58] Once contact had been established, U.S. scouts identified the location of Confederacy warriors, and Wayne ordered an immediate bayonet charge. Legion dragoons also charged and attacked with sabres. Blue Jacket's warriors fled from the battlefield to regroup nearby Fort Miami, but found themselves locked out of the fort by the British occupants. (Britain and the United States were by then reaching a close rapprochement to counter Jacobin France during the French Revolution.) The entire battle lasted little more than an hour.[28]:306 The Legion had significant casualties, with 33 men killed and 100 wounded. The Confederacy had between 19 and 40 warriors killed, and an unknown number wounded.[30]:327 The battle fostered distrust between the native nations, and between the confederacy and the British; it was the last time the Western Confederacy gathered a large military force to oppose the United States.

Wayne's army encamped for three days in sight of Fort Miamis, under command of Major William Campbell. When Major Campbell asked the meaning of the encampment, Wayne replied that the answer had already been given by the sound of their muskets and the retreat of the Indians.[11]:350 The next day, Wayne rode alone to Fort Miamis and slowly conducted an inspection of the fort's exterior walls. The British garrison debated whether or not to engage the General, but in the absence of orders and being already at war with France, Major Campbell declined to fire the first shot at the United States.[11]:350–351 The Legion, meanwhile, destroyed Indian villages and crops in the region of Fort Deposit, and burned Alexander McKee's trading post within sight of Fort Miamis before withdrawing.[11]:351

Wayne's Legion finally arrived at Kekionga on 17 September 1794, and Wayne personally selected the site for a new U.S. fort.[32]:27–28 Wayne wanted a strong fort built, capable of withstanding not only an Indian uprising, but a possible attack by the British from Fort Detroit. The fort was finished by 17 October, and was capable of withstanding 24-pound cannons. It was named Fort Wayne and placed under command of Jean François Hamtramck, who had been commandant of Fort Knox in Vincennes and had commanded the left wing at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The fort was officially dedicated 22 October,[32] the fourth anniversary of Harmar's Defeat, and the day is considered the founding of the modern city of Fort Wayne, Indiana.[60]

That winter, Wayne also reinforced his line of defensive forts with Fort St. Marys, Fort Loramie, and Fort Piqua.

Treaty of Greenville and Jay Treaty

Within months of Fallen Timbers, the United States and Great Britain negotiated the Jay Treaty,[61] which required British withdrawal from the Great Lakes forts while opening up some British territory in the Caribbean for American trade. The treaty also encoded free trade and freedom of movement for Native Americans living in territories controlled by either the United States or Great Britain.[62] The Jay Treaty was ratified by the United States Senate in 1795,[61] and was used by Wayne as evidence that Great Britain would no longer support the confederacy.[28]:328 The Jay Treaty and US relations with Great Britain remained as political issues in the 1796 United States presidential election, in which John Adams beat Jay Treaty opponent Thomas Jefferson.

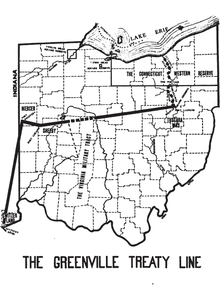

The United States also negotiated the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, signed by President Washington on 22 December 1795.[30]:366 Utilizing St. Clair's defeat and Fort Recovery as a reference point,[63] the Greenville Treaty Line forced the northwest Native American tribes to cede southern and eastern Ohio and various tracts of land around forts and settlements in Illinois Country; to recognize the U.S., rather than Britain, as the ruling power in the Old Northwest; and to surrender ten chiefs as hostages until all American prisoners were returned. The Miami also lost private control of the Kekionga portage, since the Northwest Ordinance passed by Congress guaranteed free use of important portages in the region.[32]:30

Aftermath

Fort Lernoult was abandoned by the British in 1796 as a condition of the Jay Treaty. The next day, U.S. Colonel Jean François Hamtramck occupied the fort and began making improvements. The U.S. would officially rename it to Fort Detroit. The British would re-capture Fort Detroit in August 1812, but abandon it again one year later as American forces advanced towards it.[9] The British also abandoned Fort Miami, which the U.S. occupied until 1799. Like Fort Detroit, the British re-occupied Fort Miami during the War of 1812. It was abandoned in 1814 and eventually demolished.

Most of the western U.S. forts were also abandoned after 1796; Fort Washington, the last, was moved across the Ohio River to Kentucky in 1804 to make room for a growing settlement at Cincinnati; it became the Newport Barracks.[64] General Wayne supervised the surrender of British posts in the Northwest Territory, and personally selected the construction site of Fort Wayne in Kekionga to secure his Legion's victory.[32]:27 Wayne suffered a severe attack of gout and died on 15 December 1796, one year after the ratification of the Treaty of Greenville.[30]:367

After the end of hostilities, large numbers of United States settlers migrated to the Northwest Territory. Five years after the Treaty of Greenville, the territory was split into Ohio and Indiana Territory, and in February 1803, the State of Ohio was admitted to the Union.[Note 4] The border between Ohio and the Indiana Territory closely followed the line of advanced forts and the Greenville Treaty Line.

Several veterans of the Northwest Indian War are known for their later achievements, including William Henry Harrison, William Clark and Meriwether Lewis,[65] and Tecumseh.

Future Native American resistance movements were unable to form a union matching the size or capability seen during the Northwest Indian War. In 1805, Tenskwatawa began a traditionalist movement that rejected United States practices. His followers settled at Prophetstown in Indiana Territory, leading to Tecumseh's War and the Northwest theater of the War of 1812.

Key figures

United States

- Henry Knox, first United States Secretary of War

- Josiah Harmar, Brigadier General in command of the First American Regiment who led the 1790 Harmar Campaign

- Arthur St. Clair, Governor of the Northwest Territory and Major General at St. Clair's Defeat

- Anthony Wayne, Major General in command of Legion of the United States at the Battle of Fallen Timbers

- Charles Scott, Brigadier General commanding the Kentucky militia during Wayne's campaign

- James Wilkinson, Lieutenant Colonel in command of Fort Washington, and Wayne's second in command

Indian Confederacy

- Little Turtle (Miami)

- Blue Jacket (Shawnee)

- Buckongahelas (Delaware)

- Roundhead, (or Stayeghtha) (Wyandot)

- Egushawa (Ottawa)

- Joseph Brant (Mohawk)

British Empire

- Sir Guy Carleton Commander-in-Chief of British North America

- William Campbell, British Major in command of Fort Miamis

- John Graves Simcoe Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada

- Alexander McKee British Agent to the Western Confederacy and Colonel in the Indian Department

See also

- American Indian wars

- Confederation Period

- Native Americans in the United States

- Presidency of George Washington

Notes

- "By 1783 approximately seven percent of Kentucky’s population had been killed in combat with Native Americans … the thirteen rebelling colonies had lost just one percent of their population during the Revolutionary War." Reid, Darren R. (19 June 2017). "Anti-Indian Radicalisation in the Early American West, 1774–1795". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Possibly the son of late Delaware chief White Eyes. Messengers would later refer to him as "Young White Eyes." See Hogeland, pp. 292–293

- An unknown number of Chickasaw and Choctaw warriors got behind the Native Americans at Fort Recovery and shot a number of Chippewa and Ottawa in the back. They escaped without being identified, which caused a considerable amount of distrust between the various nations within the Native American confederacy. See Gaff (2004) pp. 247–248.

- An act to provide for the due execution of the laws of the United States, within the state of Ohio, ch. 7, 2 Stat. 201 (19 February 1803).

Citations

- "Indian Wars Campaigns". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Parrott, Zach; Marshall, Tabitha (31 July 2019). "Iroquois Wars". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Preston, David (October 2019). "When Young George Washington Started a War". Washington, DC: Smithonian Institute. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- Pocock, Tom (1998). Battle for Empire. The very first World War, 1756–63. London: Michael O'Mara Books Limited. pp. 256–7. ISBN 1-84067-324-9.

- "The Royal Proclamation of 1763". U.S. History Online. 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Sobol, Thomas Thorleifur (17 February 2016). "Virginia Looking Westward: From Lord Dunmore's War Through the Revolution". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "The American Revolution, 1763–1783. British Reforms and Colonial Resistance, 1763–1766". Library of Congress. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Calloway, Colin G (2018). The Indian World of George Washington. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190652166. LCCN 2017028686.

- "Fort Lernoult". Detroit Historical Society. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Sterner, Eric (18 December 2018). "The Treaty of Fort Pitt, 1778: The First U.S.–American Indian Treaty". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Hogeland, William (2017). Autumn of the Black Snake. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374107345. LCCN 2016052193.

- Keller, Christine; Boyd, Colleen; Groover, Mark; Hill, Mark (2011). "Archeology of the Battles of Fort Recovery, Mercer County, Ohio: Education and Protection" (PDF). National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program. p. 61. Retrieved 24 November 2019 – via Ball State University.

- Sterner, Eric (6 February 2018). "Moravians in the Middle: the Gnadenhutten Massacre". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Reid, Darren R. (19 June 2017). "Anti-Indian Radicalisation in the Early American West, 1774–1795". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "American Revolution – FAQs". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Van Every, Dale (1962). "19: The War Without an End". A Company of Heroes: The American Frontier: 1775–1783 (The Frontier People of America Book 2) (Kindle ed.). Endeavour Media. p. 270.

- "Treaty and Land Transaction of 1784". National Park Service. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- "Treaty of Fort McIntosh (1785)". Ohio History Connection. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Van Every, Dale (2008) [1963]. Ark of Empire: The American Frontier: 1784–1803 (The Frontier People of America) (Kindle ed.). New York: Morrow – via Endeavour Media.

- Keiper, Karl A. (2010). "12". Land of the Indians – Indiana. p. 53. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Fort Finney". Whitewater River Foundation. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "Journals of the Continental Congress. Monday, July 24, 1786". Library of Congress. p. 429. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "A Confederation of Native peoples seek peace with the United States, 1786". The American YAWP Reader. Stanford University Press. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- "Transcript of Northwest Ordinance (1787)". OurDocuments.gov. National Archives and Records Administration. Article 3. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- Knox, Henry. "To George Washington from Henry Knox, 23 May 1789". Founders Online. National Archives. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- "1790s: Indian nations unite to fight American expansion". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- Nelson, Larry L. "Cultural Mediation on the Great Lakes Frontier: Alexander McKee and Anglo-American Indian Affairs, 1754-1799". National Park Service History Electronic Library. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- Sword, Wiley (1985). President Washington's Indian War: The Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790–1795. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2488-1.

- Barnes, Celia (2003). "7". Native American Power in the United States, 1783-1795. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 190–191 – via Rosemont Publishing and Printing Corporation.

- Gaff, Alan D. (2004). Bayonets in the Wilderness. Anthony Waynes Legion in the Old Northwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3585-9.

- Harless, Richard. "Native American Policy". George Washington's Mount Vernon. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Poinsatte, Charles (1976). Outpost in the Wilderness: Fort Wayne, 1706–1828. Allen County, Fort Wayne Historical Society.

- "Harmar's Defeat". Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- Drake (1901), p. 173-5.

- Allison, Harold (1986). The Tragic Saga of the Indiana Indians. Turner Publishing Company, Paducah. p. 76. ISBN 0-938021-07-9.

- Winkler, John F (2011). Wabash 1791. St. Clair's defeat. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-676-9.

- Buffenbarger, Thomas E. (15 September 2011). "St. Clair's Campaign of 1791: A Defeat in the Wilderness That Helped Forge Today's U.S. Army". U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- Furlong, Patrick J. (23 March 2011). "Problems of Frontier Logistics in St. Clair's 1791 Campaign". National Park Service. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- "Little Turtle (1752 – July 1812)". The Supreme Court of Ohio & The Ohio Judicial System. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- "Fort Jefferson". Ohio History Central. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- Feng, Patrick (16 July 2014). "The Battle of the Wabash: The Forgotten Disaster of the Indian Wars". National Museum of the United States Army. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Edel (1997).

- Roosevelt (1896).

- Stilwell, Blake (17 May 2019). "This is the biggest victory Natives scored against the colonials". We Are The Mighty. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Schecter, Barnet (2010). George Washington's America. A Biography Through His Maps. New York: Walker & Company. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-8027-1748-1.

- "May 08, 1792: Militia Act establishes conscription under federal law". This Day in History. New York: A&E Networks. 2009. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Heitman, F.B. (1914). Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April 1775, to December, 1783. Rare book shop publishing Company, Incorporated. p. 549. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- "Memorial for Alexander Truman". Find A Grave.

- "Major General Benjamin Lincoln". Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "Negotiations between the Western Indian Confederacy & U.S. Commissioners on the issue of the Ohio River as the boundary of Indian lands, August 1793" (PDF). National Humanities Center. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "To John Adams from Benjamin Lincoln, 11 September 1793". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Scott, Joseph C. "Anthony Wayne". George Washington's Mount Vernon. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- Nelson, Paul David (1985). Anthony Wayne, Soldier of the Early Republic. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253307511.

- Winkler (2013), p. 53.

- Hunter, Frances (23 February 2012). "The Frontier Forts of Anthony Wayne, Part 2". Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Carter, Harvey Lewis (1987). The Life and Times of Little Turtle: First Sagamore of the Wabash. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 133. ISBN 0-252-01318-2.

- Nelson, Paul D. (1986). "General Charles Scott, the Kentucky Mounted Volunteers, and the Northwest Indian Wars, 1784–1794". Journal of the Early Republic. 6 (3): 246. doi:10.2307/3122915. JSTOR 3122915.

- Seelinger, Matthew (16 July 2014). "The Battle of Fallen Timbers, 20 August 1794". National Museum of the United States Army. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Stockwell 2018, p. 264.

- "Fort Wayne: History". Allen County History Center. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- "John Jay's Treaty, 1794–95". Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute. United States Department of State. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- "First Nations and Native Americans". U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Canada. United States Department of State. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- "Treaty of Greene Ville". Touring Ohio. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Suess, Jeff (28 December 2013). "Cincinnati's beginning: The origin of the settlement that became this city". cincinnati.com. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- "Meriwether Lewis". Virginia Center for Digital History. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

References

- Barnes, Celia (2003). Native American Power in the United States, 1783–1795. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press – via Rosemont Publishing and Printing Corporation.

- Calloway, Colin G (2018). The Indian World of George Washington. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190652166. LCCN 2017028686.

- Dowd, Gregory Evans (1992). A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University.

- Drake, Samuel Adams (1901) [1899]. The Making of the Ohio Valley States: 1660–1837. ISBN 978-1-58218-422-7.

- Edel, Wilbur (1997). Kekionga! The Worst Defeat in the History of the U.S. Army. Westport: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-95821-3. LCCN 96-42274.

- Gaff, Alan D. (2004). Bayonets in the Wilderness. Anthony Waynes Legion in the Old Northwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3585-9.

- Hogeland, William (2017). Autumn of the Black Snake. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374107345. LCCN 2016052193.

- Nelson, Paul David (1985). Anthony Wayne, Soldier of the Early Republic. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253307511.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1896). St. Clair's Defeat, 1791. Fort Wayne: Fort Wayne Convention Bureau.

- Skaggs, David Curtis, ed. (1977). The Old Northwest in the American Revolution. Madison, Wisconsin: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin. ISBN 0-87020-164-6.

- Sword, Wiley (1985). President Washington's Indian War: The Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790-1795. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2488-1.

- Van Every, Dale (2018) [1962]. A Company of Heroes: The American Frontier: 1775-1783 (The Frontier People of America Book 2) (Kindle ed.). New York: William Morrow, Ltd. – via Endeavour Media.

- Van Every, Dale (2018) [1963]. Ark of Empire: The American Frontier: 1784–1803 (The Frontier People of America) (Kindle ed.). New York: Morrow – via Endeavour Media.

- Winkler, John F. (2013). Fallen Timbers 1794: The US Army's First Victory. Illustrated by Peter Dennis. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781780963754. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- Winkler, John F (2011). Wabash 1791. St. Clair's defeat. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-676-9.

Further reading

- Fernandes, Melanie L. (2016) ""Under the auspices of peace": The Northwest Indian War and its Impact on the Early American Republic," The Gettysburg Historical Journal: Vol. 15, Article 8. Available at: http://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol15/iss1/8

- Jennings, Francis (1993). The Founders of America. New York: Norton.

- Skaggs, David Curtis; Nelson, Larry L., eds. (2001). The Sixty Years' War for the Great Lakes, 1754–1814. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-569-4.

- Sugden, John (2000). Blue Jacket: Warrior of the Shawnees. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

- White, Richard (1991). The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Northwest Indian War. |