Silane

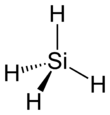

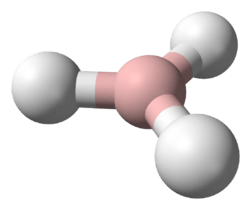

Silane is an inorganic compound with chemical formula, SiH4, making it a group 14 hydride. It is a colourless, pyrophoric, toxic gas with a sharp, repulsive smell, somewhat similar to that of acetic acid.[5] Silane is of practical interest as a precursor to elemental silicon.

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Silane | |||

| Other names

Monosilane Silicane | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.331 | ||

| 273 | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 2203 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| H4Si | |||

| Molar mass | 32.117 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colourless gas | ||

| Odor | repulsive[1] | ||

| Density | 1.313 g/L[2] | ||

| Melting point | −185 °C (−301.0 °F; 88.1 K)[2] | ||

| Boiling point | −111.9 °C (−169.4 °F; 161.2 K)[2] | ||

| Reacts slowly[2] | |||

| Vapor pressure | >1 atm (20 °C)[1] | ||

| Conjugate acid | Silanium (sometimes spelled silonium) | ||

| Structure | |||

| tetrahedral

r(Si-H) = 1.4798 angstroms[3] | |||

| 0 D | |||

| Thermochemistry[4] | |||

Heat capacity (C) |

42.8 J mol−1 K−1 | ||

Std molar entropy (S |

204.6 J mol−1 K−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

34.3 kJ/mol | ||

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG˚) |

56.9 kJ/mol | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Main hazards | Extremely flammable, pyrophoric in air | ||

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 0564 | ||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | Not applicable, pyrophoric gas | ||

| ~ 18 °C (64 °F; 291 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 1.37–100% | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

none[1] | ||

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 5 ppm (7 mg/m3)[1] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

N.D.[1] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related tetrahydride compounds |

Methane Germane Stannane Plumbane | ||

Related compounds |

Phenylsilane | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

"Silanes" refers to many compounds with four substituents on silicon, including an organosilicon compound. Examples include trichlorosilane (SiHCl3), tetramethylsilane (Si(CH3)4), and tetraethoxysilane (Si(OC2H5)4).

Production

Commercial-scale routes

Silane can be produced by several routes.[6] Typically, it arises from the reaction of hydrogen chloride with magnesium silicide:

- Mg2Si + 4 HCl → 2 MgCl2 + SiH4

It is also prepared from metallurgical grade silicon in a two-step process. First, silicon is treated with hydrogen chloride at about 300 °C to produce trichlorosilane, HSiCl3, along with hydrogen gas, according to the chemical equation:

- Si + 3 HCl → HSiCl3 + H2

The trichlorosilane is then converted to a mixture of silane and silicon tetrachloride. This redistribution reaction requires a catalyst:

- 4 HSiCl3 → SiH4 + 3 SiCl4

The most commonly used catalysts for this process are metal halides, particularly aluminium chloride. This is referred to as a redistribution reaction, which is a double displacement involving the same central element. It may also be thought of as a disproportionation reaction even though there is no change in the oxidation number for silicon (Si has a nominal oxidation number IV in all three species). However, the utility of the oxidation number concept for a covalent molecule, even a polar covalent molecule, is ambiguous. The silicon atom could be rationalized as having the highest formal oxidation state and partial positive charge in SiCl4 and the lowest formal oxidation state in SiH4 since Cl is far more electronegative than is H.

An alternative industrial process for the preparation of very high purity silane, suitable for use in the production of semiconductor grade silicon, starts with metallurgical grade silicon, hydrogen, and silicon tetrachloride and involves a complex series of redistribution reactions (producing byproducts that are recycled in the process) and distillations. The reactions are summarized below:

- Si + 2 H2 + 3 SiCl4 → 4 SiHCl3

- 2 SiHCl3 → SiH2Cl2 + SiCl4

- 2 SiH2Cl2 → SiHCl3 + SiH3Cl

- 2 SiH3Cl → SiH4 + SiH2Cl2

The silane produced by this route can be thermally decomposed to produce high-purity silicon and hydrogen in a single pass.

Still other industrial routes to silane involve reduction of SiF4 with sodium hydride (NaH) or reduction of SiCl4 with lithium aluminum hydride (LiAlH4).

Another commercial production of silane involves reduction of silicon dioxide (SiO2) under Al and H2 gas in a mixture of NaCl and aluminum chloride (AlCl3) at high pressures:[7]

- 3 SiO2 + 6 H2 + 4 Al → 3 SiH4 + 2 Al2O3

Laboratory-scale routes

In 1857, the German chemists Heinrich Buff and Friedrich Woehler discovered silane among the products formed by the action of hydrochloric acid on aluminum silicide, which they had previously prepared. They called the compound siliciuretted hydrogen.[8]

For classroom demonstrations, silane can be produced by heating sand with magnesium powder to produce magnesium silicide (Mg2Si), then pouring the mixture into hydrochloric acid. The magnesium silicide reacts with the acid to produce silane gas, which burns on contact with air and produces tiny explosions.[9] This may be classified as a heterogeneous acid-base chemical reaction since the isolated Si4 − ion in the Mg2Si antifluorite structure can serve as a Brønsted–Lowry base capable of accepting four protons. It can be written as:

- 4 HCl + Mg2Si → SiH4 + 2 MgCl2

In general, the alkaline-earth metals form silicides with the following stoichiometries: MII2Si, MIISi, and MIISi2. In all cases, these substances react with Brønsted–Lowry acids to produce some type of hydride of silicon that is dependent on the Si anion connectivity in the silicide. The possible products include SiH4 and/or higher molecules in the homologous series SinH2n+2, a polymeric silicon hydride, or a silicic acid. Hence, MIISi with their zigzag chains of Si2 − anions (containing two lone pairs of electrons on each Si anion that can accept protons) yield the polymeric hydride (SiH2)x.

Yet another small-scale route for the production of silane is from the action of sodium amalgam on dichlorosilane, SiH2Cl2, to yield monosilane along with some yellow polymerized silicon hydride (SiH)x.[10]

Properties

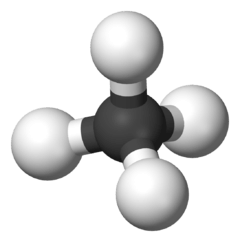

Silane is the silicon analogue of methane. Because of the greater electronegativity of hydrogen in comparison to silicon, this Si–H bond polarity is the opposite of that in the C–H bonds of methane. One consequence of this reversed polarity is the greater tendency of silane to form complexes with transition metals. A second consequence is that silane is pyrophoric — it undergoes spontaneous combustion in air, without the need for external ignition.[11] However, the difficulties in explaining the available (often contradictory) combustion data are ascribed to the fact that silane itself is stable and that the natural formation of larger silanes during production, as well as the sensitivity of combustion to impurities such as moisture and to the catalytic effects of container surfaces causes its pyrophoricity.[12][13] Above 420 °C, silane decomposes into silicon and hydrogen; it can therefore be used in the chemical vapor deposition of silicon.

The Si–H bond strength is around 384 kJ/mol, which is about 20% weaker than the H–H bond in H2. Consequently, compounds containing Si–H bonds are much more reactive than is H2. The strength of the Si–H bond is modestly affected by other substituents: the Si–H bond strengths are: SiHF3 419 kJ/mol, SiHCl3 382 kJ/mol, and SiHMe3 398 kJ/mol.[14][15]

Applications

---No%2C1_%E3%80%90_Pictures_taken_in_Japan_%E3%80%91.jpg)

While diverse applications exist for organosilanes, silane itself has one dominant application, as a precursor to elemental silicon, particularly in the semiconductor industry. The higher silanes, such as di- and trisilane, are only of academic interest. About 300 metric tons per year of silane were consumed in the late 1990s.[13] Low-cost solar photovoltaic module manufacturing has led to substantial consumption of silane for depositing (PECVD) hydrogenated amorphous silicon (a-Si:H) on glass and other substrates like metal and plastic. The PECVD process is relatively inefficient at materials utilization with approximately 85% of the silane being wasted. To reduce that waste and the ecological footprint of a-Si:H-based solar cells further several recycling efforts have been developed.[16][17]

Safety and precautions

A number of fatal industrial accidents produced by combustion and detonation of leaked silane in air have been reported.[18][19][20]

Silane is a pyrophoric gas (capable of autoignition at temperatures below 54 °C /130 °F).[21]

- SiH4 + O2 → SiO2 + 2 H2

- SiH4 + O2 → SiH2O + H2O

- 2 SiH4 + O2 → 2 SiH2O + 2H2

- SiH2O + O2 → SiO2 + H2O

For lean mixtures a two-stage reaction process has been proposed, which consists of a silane consumption process and a hydrogen oxidation process. The heat of SiO2 (s) condensation increases the burning velocity due to thermal feedback.[22]

Diluted silane mixtures with inert gases such as nitrogen or argon are even more likely to ignite when leaked into open air, compared to pure silane: even a 1% mixture of silane in pure nitrogen easily ignites when exposed to air.[23]

In Japan, in order to reduce the danger of silane for amorphous silicon solar cell manufacturing, several companies began to dilute silane with hydrogen gas. This resulted in a symbiotic benefit of making more stable solar photovoltaic cells as it reduced the Staebler-Wronski Effect.

Unlike methane, silane is fairly toxic: the lethal concentration in air for rats (LC50) is 0.96% (9,600 ppm) over a 4-hour exposure. In addition, contact with eyes may form silicic acid with resultant irritation.[24]

In regards to occupational exposure of silane to workers, the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has set a recommended exposure limit of 5 ppm (7 mg/m3) over an eight-hour time-weighted average.[25]

See also

- Silanes

- Silanization

- Magnesium silicide

References

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0556". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Haynes, p. 4.87

- Haynes, p. 9.29

- Haynes, p. 5.14

- CFC Startec properties of Silane Archived 2008-03-19 at the Wayback Machine. C-f-c.com. Retrieved on 2013-03-06.

- Simmler, W. "Silicon Compounds, Inorganic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_001.

- Shriver and Atkins. Inorganic Chemistry (5th Edition). W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, 2010, p. 358.

- Mellor, J. W. "A Comprehensive Treatise on Inorganic and Theoretical Chemistry," Vol VI, Longmans, Green and Co. (1947), p. 216.

- Making Silicon from Sand Archived 2010-11-29 at the Wayback Machine, by Theodore Gray. Originally published in Popular Science magazine.

- Mellor, J. W. "A Comprehensive Treatise on Inorganic and Theoretical Chemistry, Vol. VI" Longmans, Green and Co. (1947) pp. 970–971.

- Emeléus, H. J. & Stewart, K. (1935). "The oxidation of the silicon hydrides". Journal of the Chemical Society: 1182–1189. doi:10.1039/JR9350001182.

- Koda, S. (1992). "Kinetic Aspects of Oxidation and Combustion of Silane and Related Compounds". Progress in Energy and Combustion Science. 18 (6): 513–528. doi:10.1016/0360-1285(92)90037-2.

- Timms, P. L. (1999). "The chemistry of volatile waste from silicon wafer processing". Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions (6): 815–822. doi:10.1039/a806743k.

- M. A. Brook "Silicon in Organic, Organometallic, and Polymer Chemistry" 2000, J. Wiley, New York. ISBN 0-471-19658-4.

- "Bond Energies". Michigan State University Organic Chemistry. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-11-21. Retrieved 2017-06-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Briend P, Alban B, Chevrel H, Jahan D. American Air, Liquide Inc. (2009) "Method for Recycling Silane (SiH4)". US20110011129 Archived 2013-09-22 at the Wayback Machine, EP2252550A2 Archived 2013-09-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- Kreiger, M.A.; Shonnard, D.R.; Pearce, J.M. (2013). "Life cycle analysis of silane recycling in amorphous silicon-based solar photovoltaic manufacturing". Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 70: 44–49. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2012.10.002. Archived from the original on 2017-11-12.

- Chen, J. R. (2002). "Characteristics of fire and explosion in semiconductor fabrication processes". Process Safety Progress. 21 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1002/prs.680210106.

- Chen, J. R.; Tsai, H. Y.; Chen, S. K.; Pan, H. R.; Hu, S. C.; Shen, C. C.; Kuan, C. M.; Lee, Y. C. & Wu, C. C. (2006). "Analysis of a silane explosion in a photovoltaic fabrication plant". Process Safety Progress. 25 (3): 237–244. doi:10.1002/prs.10136.

- Chang, Y. Y.; Peng, D. J.; Wu, H. C.; Tsaur, C. C.; Shen, C. C.; Tsai, H. Y. & Chen, J. R. (2007). "Revisiting of a silane explosion in a photovoltaic fabrication plant". Process Safety Progress. 26 (2): 155–158. doi:10.1002/prs.10194.

- Silane MSDS Archived 2014-05-19 at the Wayback Machine

- V.I Babushok (1998). "Numerical Study of Low and High Temperature Silane Combustion". The Combustion Institute. 27th Symposium (2): 2431–2439. doi:10.1016/S0082-0784(98)80095-7.

- Kondo, S.; Tokuhashi, K.; Nagai, H.; Iwasaka, M. & Kaise, M. (1995). "Spontaneous Ignition Limits of Silane and Phosphine". Combustion and Flame. 101 (1–2): 170–174. doi:10.1016/0010-2180(94)00175-R.

- MSDS for silane Archived 2009-02-20 at the Wayback Machine. vngas.com

- "Silicon tetrahydride". NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 4, 2011. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

Cited sources

- Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1439855119.