Economic history of Mexico

Mexico's economic history has been characterized since the colonial era by resource extraction, agriculture, and a relatively underdeveloped industrial sector. Economic elites in the colonial period were predominantly Spanish born, active as transatlantic merchants and silver mine owners and diversifying their investments with the landed estates. The largest sector of the population was indigenous subsistence farmers, who lived mainly in the center and south.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Mexico |

|

|

Spanish rule |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

New Spain was envisioned by the Spanish crown as a supplier of wealth to Iberia, which huge silver mines accomplished. A colonial economy to supply foodstuffs and products from ranching as well as a domestic textile industry meant that the economy supplied much of its own needs. Crown economic policy rattled American-born elites’ loyalty to Spain when in 1804 it instituted a policy to make mortgage holders pay immediately the principal on their loans, threatening the economic position of cash-strapped land owners.[1] Independence in Mexico in 1821 was economically difficult for the country, with the loss of its supply of mercury from Spain in silver mines.[2]

Most of the patterns of wealth in the colonial era continued into the first half of the nineteenth century, with agriculture being the main economic activity with the labor of indigenous and mixed-race peasants. The mid-nineteenth-century Liberal Reforma (ca. 1850–1861; 1867–76) attempted to decrease the economic power of the Roman Catholic Church and to modernize and industrialize the Mexican economy. Following civil war and a foreign intervention, the late nineteenth century found political stability and economic prosperity during the presidential regime of General Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911). Mexico was opened to foreign investment and, to a lesser extent, foreign workers. Foreign capital built a railway network, one of the keys for transforming the Mexican economy, by linking regions of Mexico and major cities and ports. As the construction of the railway bridge over a deep canyon at Metlac demonstrates, Mexico's topography was a barrier to economic development. The mining industry revived in the north of Mexico and the petroleum industry developed in the north Gulf Coast states with foreign capital.

Regional civil wars broke out in 1910 and lasted until 1920, known generally as the Mexican Revolution. Following the military phase of the Revolution, Mexican regimes attempted to "transform a largely rural and backward country … into a middle-sized industrial power."[3] The Mexican Constitution of 1917 gave the Mexican government the power to expropriate property, which allowed for the distribution of land to peasants, but also the Mexican oil expropriation in 1938. Mexico benefited economically from its participation in World War II and the post-war years experienced what has been called the Mexican Miracle (ca. 1946–1970). This growth was fueled by import substitution industrialization. The Mexican economy experienced the limits of ISI and economic nationalism and Mexico sought a new model for economic growth. Huge oil reserves were discovered in the Gulf of Mexico in the late 1970s and Mexico borrowed heavily from foreign banks with loans denominated in U.S. dollars. When the price of oil dropped in the 1980s, Mexico experienced a severe financial crisis.

Under President Carlos Salinas de Gortari Mexico campaigned to join the North American Free Trade Agreement with the expanded treaty going into effect in Mexico, the U.S., and Canada on January 1, 1994. Mexico implemented neoliberal economic policies and changed significant articles of the Mexican Constitution of 1917 to ensure private property rights against future nationalization. In the twenty-first century, Mexico has strengthened its trade ties with China, but Chinese investment projects in Mexico have hit roadblocks in 2014–15. Mexico's continued dependence on oil revenues has had a deleterious impact when oil prices drop, as is happening 2014–15.[4]

Economy of New Spain, 1521–1821

Mexico's economy in the colonial period was based on resource extraction (mainly silver), on agriculture and ranching, and on trade, with manufacturing playing a minor role. In the immediate post-conquest period (1521–40), the dense indigenous and hierarchically organized central Mexican peoples were a potential ready labor supply and producers of tribute goods. Indian communities' tribute and labor (but not land) were granted to individual conquerors in an arrangement called encomienda. Conquerors built private fortunes less from the plunder of the brief period of conquest than from the labor and tribute and the acquisition of land in areas where they held encomiendas, translating that into long-term sustainable wealth.[5][6]

The colonial landscape in central Mexico became a patchwork of different sized holdings by Spaniards and indigenous communities. As the crown began limiting the encomienda in the mid-sixteenth century to prevent the development of an independent seigneurial class, Spaniards who had become land owners acquired permanent and part-time labor from Indian and mixed-race workers. Although the encomienda was a major economic institution of the early period, in the end it was a transitory phase, due to the drop in the indigenous populations due to virgin land epidemics of diseases brought by Europeans, but also importantly rapid economic growth and the expansion of the number of Spaniards in New Spain.[7]

Mining

Silver became the motor of the Spanish colonial economy both in New Spain and in Peru. It was mined under license from the crown, with a fifth of the proceeds (quinto real) rendered to the crown.[8] Although the Spaniards sought gold, and there were some small mines in Oaxaca and Michoacan, the big transformation in New Spain's economy came in the mid-sixteenth century with discoveries of large deposits of silver.[9] Close to Mexico City, the Nahua settlement of Taxco was found in 1534 to have silver.[10]

But the biggest strikes were in the north outside the zone of dense indigenous communities and Spanish settlement. Zacatecas and later Guanajuato became the most important centers of silver production, but there were many others, including in Parral (Chihuahua) and later strikes in San Luis Potosí, optimistically named after the famous Potosí silver mine of Peru.[9] Spaniards established of cities in the mining region as well as agrarian enterprises supplying foodstuffs and material goods necessary for the mining economy. For Mexico, which did not have a vast supply of trees to use as fuel to extract silver from ore by high heat, the invention in 1554 of the patio process that used mercury to chemically extract the silver from ore was a breakthrough.[11] Spain had a mercury mine in Almadén whose mercury was exported to Mexico. (Peru had its own local source of mercury at Huancavelica). The higher the proportion of mercury in the process meant the higher the extraction of silver.

_carretilla_en_una_galer%C3%ADa.png)

The crown had a monopoly on mercury and set its price. During the Bourbon reforms of the eighteenth century, the crown increased mercury production at Almadén and lowered the price to miners by half resulting in a huge increase in Mexico's silver production.[12] As production costs dropped, mining became less risky so that there was a new surge of mine openings and improvements.[13] In the eighteenth century, mining was professionalized and elevated in social prestige with the establishment of the royal college of mining and a miners' guild (consulado), making mining more respectable. The crown promulgated a new mining code that limited liability and protected patents as technical improvements were developed.[14] Highly successful miners purchased titles of nobility in the eighteenth century, valorizing their status in society as well as bringing revenues to the crown.[15][16]

Wealth from Spanish mining fueled the transatlantic economy, with silver becoming the main precious metal in circulation worldwide. Although the northern mining did not itself become the main center of power in New Spain, the silver extracted there was the most important export from the colony.[17] The control that the royal mints exerted over the uniform weight and quality of silver bars and coins made Spanish silver the most accepted and trusted currency.

Many of the laborers in the silver mines were free wage earners drawn by high wages and the opportunity to acquire wealth for themselves through the pepena system[18] which allowed miners to take especially promising ore for themselves.[19] There was a brief period of mining in central and southern Mexico that mobilized indigenous men's involuntary labor by the repartimiento, but Mexico's mines developed in the north outside of the zone of dense indigenous settlement. They were ethnically mixed and mobile, becoming culturally part of the Hispanic sphere even if their origins were indigenous. Mine workers were generally well paid with a daily wage of 4 reales per day plus a share of the ore produced, the partido. In some cases, the partido was worth more than the daily wage. Mine owners sought to terminate the practice.[15] Mine workers pushed back against mine owners, particularly in a 1766 strike at the Real del Monte mine, owned by the Conde de Regla, in which they closed down the mine and murdered a royal official.[20] In the colonial period, mine workers were the elites of free workers,[21]

Agriculture and ranching

Although pre-Hispanic Mexico produced surpluses of corn (maize) and other crops for tribute and subsistence use, Spaniards began commercial agriculture, cultivating wheat, sugar, fruit trees, and even for a period, mulberry trees for silk production in Mexico.[22][23] Areas that had never seen indigenous cultivation became important for commercial agriculture, particularly what has been called the "near North" of Mexico, just north of indigenous settlement in central Mexico. Wheat cultivation using oxen and Spanish plows was done in the Bajío, a region that includes a number of states of modern Mexico, Querétaro, Jalisco, and San Luis Potosí.

The system of land tenure has been cited as one of the reasons that Mexico failed to develop economically during the colonial period, with large estates inefficiently organized and run and the "concentration of land ownership per se caused waste and misallocation of resources."[24] These causes were posited before a plethora of studies of the hacienda and smaller agrarian enterprises as well as broader regional studies were done in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. These meticulous studies of individual haciendas and regions over time demonstrates that hacienda owners were profit-seeking entrepreneurs. They had the advantage of economies of scale that smaller holders and Indian villages did not in cultivation of grains, pulque, sugar, and sisal and in ranching, with cattle and sheep.[25] Great haciendas did not completely dominate the agrarian sector, since there were products that could be efficiently produced by smaller holders and Indian villages, such as fruits and vegetables, cochineal red dye, and animals that could be raised in confined spaces, such as pigs and chickens.[26] Small holders also produced wine, cotton and tobacco.[26] In the eighteenth century, the crown created a tobacco monopoly on both cultivation and manufacturing of tobacco products.[27]

As Spanish agrarian enterprises developed, acquiring title to land became important. As the size of the indigenous labor force dropped and as the number of Spaniards seeking land and access to labor increased, a transitional labor institution called repartimiento ("allotment") developed, in which the crown allotted indigenous labor to Spaniards on a temporary basis. Many Spanish landowners found the system unsatisfactory since they could not count on receiving an allocation that suited their needs. The repartimiento for agriculture was abolished in 1632.[28] Large-scale landed estates or haciendas developed, and most needed both a small permanent labor force supplemented by temporary labor at peak times, such as planting and harvesting.[29][30]

Cattle ranching need far less labor than agriculture, but did need sufficient grazing land for their herds to increase. As more Spaniards settled in the central areas of Mexico where there were already large numbers of indigenous settlements, the number of ranching enterprises declined and ranching was pushed north. Northern Mexico was mainly dry and its indigenous population nomadic or semi-nomadic, allowing Spanish ranching activities to expand largely without competition. As mining areas developed in the north, Spanish haciendas and ranches supplied products from cattle, not just meat, but hides and tallow, for the silver mining areas. Spaniards also grazed sheep, which resulted in ecological decline since sheep cropped grass to its roots preventing regeneration.[31] Central Mexico attracted a larger proportion of Spanish settlement and landed enterprises there shifted from mixed agriculture and ranching to solely agriculture. Ranching was more widespread in the north, with its vast expanses and little access to water. Spaniards imported seeds for production of wheat for their own consumption.

Both Spaniards and Indians produced native products commercially, particular the color-fast red dye cochineal, as well as the fermented juice of the maguey cactus, pulque. In the early colonial period Mexico was briefly a silk producer. When the transpacific trade with Manila developed in the late sixteenth century, the finer quality Asian silks out-competed locally produced ones.[32] The bulk of luxury yard goods were imported from northern Europe via Spain. For rough cloth for the urban masses, cotton and wool were produced and woven in Mexico in small workshops called obrajes.[33]

Cities, trade and transportation routes

Cities had concentrations of crown officials, high ecclesiastical officials, merchants, and artisans, with the viceregal capital of Mexico City, having the largest. Mexico City was founded on the ruins of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan and has never given up its primacy in Mexico. The history of Mexico City is deeply entwined in the development of the Mexican economy. Two main ports, Veracruz on the Caribbean coast the served the transatlantic trade and Acapulco on the Pacific coast, the terminus for the Asian trade via the Manila Galleon, allowed the crown to regulate trade. In Spain the House of Trade (Casa de Contratación) in Seville registered and regulated exports and imports as well as issuing licenses for Spaniards emigrating to the New World. Exports were silver and dyestuffs and imported were luxury goods from Europe, while a local economy of high bulk, low value products were produced in Mexico. Artisans and workers of various types provided goods and services to urban dwellers. In Mexico City and other Spanish settlements, the lack of a system of potable water meant that the services of water carriers supplied individual households.

A network of cities and towns developed, some were founded on previous indigenous city-states, (such as Mexico City) while secondary cities were established as]] provincial areas gained population because of economic activity. The main axis was from Veracruz, via the well-situated city of Puebla to Mexico City. Another axis connected Mexico City and Puebla to the mining areas of the north, centered on Guanajuato and Zacatecas. There was a road further north to New Mexico, but Mexico's far north, except for a few mining centers such as Parral, were of little economic interest. California's rich deposits of gold were unknown in the colonial era and had they been discovered that whole region's history would not be one of marginal importance.[34] To the south, trunk lines connected Mexico's center to Oaxaca and the port of Acapulco, the terminus of the Manila galleon. Yucatán was more easily accessed from Cuba than Mexico City, but it had a dense Maya population so there was a potential labor force to produce products such as sugar, cacao, and later henequen (sisal).

Bad transportation was a major stumbling block to the movement of goods and people within Mexico, which had generally difficult topography. There were few paved roads and dirt tracks turned impassible during the rainy season. Rather than hauling goods by carts drawn by oxen or mules, the most common mode of transporting goods was via pack mules. Poor infrastructure was coupled with poor security, so that banditry was an impediment to the safe transport of people and goods. In the Northern area, the índios bárbaros or uncivilized Indians presented a threat to settlement and travel.

The eighteenth century saw New Spain increase the size and complexity of its economy. Silver remained the motor of the economy, and in fact production increased even though few new mines came into production. The key to the increased production was the lowering of the price of mercury, an essential element in refining silver. The larger the amount of mercury used in refining, the greater pure silver was extracted from ore. Another important element for the eighteenth-century economic boom was the number of wealthy Mexicans who were involved in multiple enterprises as owners, investors, or creditors. Mining is an expensive and uncertain extractive enterprise needed large capital investments for digging and shoring up shafts as well as draining water as mines got deeper.

Elites invested their fortunes in real estate, mainly in rural enterprises and to a lesser extent urban properties, but often lived in nearby cities or the capital. The Roman Catholic Church functioned as a mortgage bank for elites. The Church itself accrued tremendous wealth, aided by the fact that as a corporation, its holdings were not broken up to distribute to heirs.

Crown policy and economic development

Crown policies generally impeded entrepreneurial activity in New Spain, through laws and regulations that were disincentives to the creation of new enterprises.[35] There was no well-defined or enforceable set of property rights,[36][37] but the crown claimed rights over subsoil resources, such as mining. The crown's lack of investment in a good system of paved roads made moving products to market insecure and expensive, so enterprises had a narrower reach for their products, particularly bulky agricultural products.[38]

Although many enterprises, such as merchant houses and mining, were highly profitable, they were often family firms. The components of Roman Catholic Church had a considerable number of landed estates and the Church received income from the tithe, a ten percent tax on agricultural output. However, there were no laws that promoted "economies of scale through joint stock companies or corporations."[37] There were corporate entities, particularly the Church and indigenous communities, but also corporate groups with privileges (fueros), such as miners and merchants who had separate courts and exemptions.[39][40][41][42]

There was no equal standing before the law, given the exemptions of corporate entities (including indigenous communities) and legal distinctions between races. Only those defined as Spaniards, either peninsular- or American-born of legitimate birth had access to a variety of elite privileges such as civil office holding, ecclesiastical positions, but also entrance of women into convents, which necessitated a significant dowry. A convent for Indian women of "pure blood" was established in the eighteenth century. Indian men from the mid-sixteenth century had been barred from the priesthood, not only excluding them from empowerment in the spiritual realm, but also depriving them of the honor, prestige, and income that a priest could garner.

In the eighteenth century the Bourbon administrative reforms began restricting the number of American-born men appointed to office, which was not only a diminution of their own and their families’ status, but also excluded them from the revenues and other benefits that flowed from office holding. The benefits were not merely the salary, but also the networks of useful connections to do business.

The interventionist and pervasively arbitrary nature of the institutional environment forced every enterprise, urban or rural, to operate in a highly politicized manner, using kinship networks, political influence, and family prestige to gain privileged access to subsidized credit, to aid various stratagems for recruiting labor, to collect debts or enforce contracts, to evade taxes or circumvent courts, and to defend titles to land.[43]

The most closely controlled commodity from New Spain (and Peru) was the production and transportation of silver. Crown officials monitored each step of the process, from licensing on those who developed mines, to transportation, to minting of uniform size and quality silver bars and coins. |

| Silver 8 real coin of Charles III of Spain, 1776 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Obverse CAROLUS III DEI GRATIA 1776 "Charles III by the Grace of God, 1776" Right profile of Charles III in toga with laurel wreath. |

Reverse HISPAN[IARUM] ET IND[IARUM] REX M[EXICO] 8 R[EALES] F M "King of the Spains and the Indies, Mexico [City Mint], 8 reales" Crowned Spanish arms between the Pillars of Hercules adorned with PLVS VLTRA motto. |

The crown established monopolies in other commodities, most importantly mercury from Almadén, the key component in silver refining. But the crown also established monopolies over tobacco production and manufacturing. Guilds (gremios) restricted the practice of certain professions, such as those engaged in painting, gilded framer makers, music instrument makers, and others. Indians and mixed–race castas were considered a threat, producing quality products far more cheaply.[44]

The crown sought to control trade and emigration to its overseas territories via the House of Trade (Casa de Contratación), based in Seville. Officials in Seville registered ships’ cargoes and passengers bound for the Indies (as the crown to the end of the colonial era called its territories) and upon arrival in New World ports, other crown officials inspected cargo and passengers. In Mexico, the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz, New Spain's oldest Spanish city and main port, and the Pacific coast port of Acapulco, the terminus of the Manila Galleon were busy when ships were in port, but they did not have large numbers of Spanish settlers in large part due to their disagreeable tropical climate.

Restricting trade put big merchant houses, largely family businesses, in a privileged position. A consulado, the organization of elite merchants, was established in Mexico City, which raised the status of merchants, and later consulados were established in Veracruz, Guadalajara, and Guatemala City indicating the growth of a core economic group in those cities.[45] Central regions could get imports those firms handled relatively easily, but with a bad transportation network, other regions became economic backwaters and smuggling and other non-sanctioned economic activity took place. The economic policy of comercio libre that was instituted in 1778, it was not full free trade but trade between ports in the Spanish empire and those in Spain; it was designed to stimulate trade. In Mexico, the big merchant families continued to dominate trade, with the main merchant house in Mexico City and smaller outlets staffed by junior members of the family in provincial cities.[46] For merchants in Guatemala City dealing in indigo, they had direct contact with merchants in Cádiz, the main port in Spain, indicating the level of importance of this dye stuff in trade as well as the strengthening of previously remote areas with larger trade networks, in this case by passing Mexico City merchant houses.[47] There was increased commercial traffic between New Spain, New Granada (northern South America), and Peru and during wartime, trade was permitted with neutral countries.[48]

Internal trade in Mexico was hampered by taxes and levies by officials. The alcabala or sales tax was established in Spain in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and was especially favored by the crown because in Spain it did not fall under the jurisdiction of the cortes or Spanish assembly.[49] Goods produced by or for Indians were exempted from the alcabala.[50] In the eighteenth century, with more effective collection of the sales tax, the revenues increased significantly.[51] Other taxes included the tithe, which was a ten percent tax on agricultural production; tributes paid by non-whites (Indians, Blacks and mixed-race castas); and fees for licensing and other government regulation. Crown officials (with the exception of the viceroy) often purchased their offices, with the price recouped through fees and other means.[52] During the late eighteenth century with the Bourbon reforms, the crown established a new administrative system, the intendancy, with much better paid crown officials, with the hope that graft and other personal enrichment would not be so tempting.[53] In the eighteenth century, there were new and increased taxes including on maize, wheat flour, and wood.[54] Fluctuations in rainfall and harvests played havoc with the price of maize, which often resulted in civil unrest, such that the crown began establishing granaries (alhondigas) to moderate the fluctuations and to forestall rioting.

In a major move to tap what it thought was a major source of revenue, the crown in 1804 promulgated the Act of Consolidation (Consolidación de Vales Reales), in which the crown mandated that the church turn over its funds to the crown, which would in turn pay the church five percent on the principal.[55] Since the church was the major source of credit for hacendados, miners, and merchants, the new law meant that they had to pay the principal to the church immediately. For borrowers who counted on thirty or more year mortgages to repay the principal, the law was a threat to their economic survival. For conservative elements in New Spain that were loyal to the crown, this most recent change in policy was a blow. With the Napoleonic invasion of Iberia in 1808, which placed Napoleon's brother Joseph on the Spanish throne, an impact in New Spain was to suspend the implementation on the deleterious Act of Consolidation.[56][57][58]

A Spanish intellectual Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos wrote a critique of the decline of Spain as an economic power in 1796 that contended the stagnation of Spanish agriculture was a major cause of Spain's economic problems. He recommended that the crown press for major changes in the agrarian sector, including the breakup of entailed estates, sale of common lands to individuals, and other instruments to make agriculture more profitable.[59] In New Spain, the bishop-elect of the diocese of Michoacan, Manuel Abad y Queipo, was influenced by Jovellanos's work and proposed similar measures in Mexico. The bishop-elect's proposal for land reform in Mexico in the early nineteenth century, influenced by Jovellanos's from the late eighteenth century, had a direct impact on Mexican liberals seeking to make the agrarian sector more profitable. Abad y Queipo "fixed upon the inequitable distribution of property as the chief cause of New Spain's social squalor and advocated ownership of land as the chief remedy."[60] At the end of the colonial era, land was concentrated in large haciendas and the vast number of peasants had insufficient land and the agrarian sector stagnated.

From the era of independence to the Liberal Reform, 1800–1855

Late colonial era and independence, 1800–22

In the late colonial era, the Spanish crown had implemented what has been called a "revolution in government", which significantly realigned New Spain's administration with significant economic impacts.[40] When the Napoleonic invasion of Iberia ousted the Bourbon monarch, there was a significant period of political instability in Spain and Spain's overseas possessions, as many elements of society viewed Joseph Napoleon as an illegitimate usurper of the throne. In 1810, with the massive revolt led by secular cleric Miguel Hidalgo rapidly expanded into a social upheaval of Indians and mixed-race castas that targeted Spaniards (both peninsular-born and American-born) and their properties. American-born Spaniards who might have opted for political independence retrenched and supported to conservative elements and the insurgency for independence was a small regional struggle. In 1812, Spanish liberals adopted a written constitution that established the crown as a constitutional monarch and limited the power of the Roman Catholic Church.

When the Bourbon monarchy was restored in 1814, Ferdinand VII swore allegiance to the constitution, but almost immediately reneged and returned to autocratic rule and asserted his rule being "by the grace of God" as the 8 real silver of coin minted in 1821 asserts.[61] Anti-French forces, particularly the British, had enabled the return of Ferdinand VII to the throne. Ferdinand's armed forces were to be sent to its overseas empire to reverse the gains that many colonial regions had gained. However, the troops mutinied and prevented a renewed assertion of royal control in the Indies.[62]

| Silver 8 real coin of Ferdinand VII of Spain, 1821 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Obverse FERDIN[ANDUS] VII DEI GRATIA 1821"Ferdinand VII by the Grace of God, 1821." Right profile of Ferdinand VII with cloak and laurel wreath. |

Reverse HISPAN[IARUM] ET IND[IARUM] REX M[EXICO] 8 R[EALES] I I"King of the Spains and the Indies, Mexico [City Mint], 8 reales." Crowned Spanish arms between the Pillars of Hercules adorned with PLVS VLTRA motto. |

In 1820, Spanish liberals staged a coup and forced Ferdinand to reinstate the Spanish Constitution of 1812 passed by the Cortes of Cádiz. For elites in New Spain, the specter of liberal policies that would have a deleterious impact on their social and economic position propelled former royalists to join the insurgent cause, thus bringing about Mexican independence in 1821. A pact between former royalist officer Agustín de Iturbide and insurgent Vicente Guerrero unified under the Plan de Iguala and the Army of the Three Guarantees brought about Mexican independence in September 1821. Rather than the insurgency being a social revolution, in the end it allowed conservative forces in now independent Mexico to remain at the top of the social and economic system.

Although independence might have brought about rapid economic growth in Mexico since the Spanish crown was no longer the sovereign, Mexico's economic position in 1800 was far better than it would be for over the next hundred years.[63] In many ways the colonial economic system remained largely in place, despite the transition to formal political independence.

At the end of the colonial era, there was no national market and only poorly developed regional markets. The largest proportion of the population was poor, both peasants, who worked small holdings for subsistence or worked for low wages, and urban dwellers, most of whom were underemployed or unemployed, with only a small artisan sector. Although New Spain had been the major producer of silver and the greatest source of income for the Spanish crown, Mexico ceased to produce silver in any significant amounts until the late nineteenth century. Poor transportation, the disappearance of a ready source of mercury from Spain, and deterioration and destruction of deep mining shafts meant that the motor of Mexico's economy ground to a halt. A brief period of monarchic rule in the First Mexican Empire ended with a military coup in 1822 and the formation of a weak federated republic under the Constitution of 1824.

Early republic to 1855

The early post-independence period in Mexican was organized as a federal republic under the Constitution of 1824. The Mexican state was a weak institution, with regional struggles between those favoring federalism and a weak central government versus those favoring a strong central government with states subordinate to it. The weakness of the state contrasts with the strength of Roman Catholic Church in Mexico, which was the exclusive religious institution with spiritual power, but it was also a major holder of real estate and source of credit for Mexican elites. The Mexican military was also a stronger institution than the state, and intervened in politics on a regular basis. Local militias also continued to exist, with the potential for both enforcing order and creating disorder.

The new republic's situation did not promote economic growth and development.[64][65] The British established a network of merchant houses in the major cities. However, according to Hilarie J. Heath, the results were bleak:

- Trade was stagnant, imports did not pay, contraband drove prices down, debts private and public went unpaid, merchants suffered all manner of injustices and operated at the mercy of weak and corruptible governments, commercial houses skirted bankruptcy.[66]

The early republic has often been called the "Age of Santa Anna," a military hero, participant in the coup ousting emperor Augustín I during Mexico's brief post-independence monarchy. He was president of Mexico on multiple occasions, seeming to prefer having the job rather than doing the job. Mexico in this period was characterized by the collapse of silver exports, political instability, and foreign invasions and conflicts that lost Mexico a huge area of its North.

The social hierarchy in Mexico was modified in the early independence era, such that racial distinctions were eliminated and the formal bars to non-whites' upward mobility were eliminated. When the Mexican republic was established in 1824, noble titles were eliminated, however, special privileges (fueros) of two corporate groups, churchmen and the military, remained in force so that there were differential legal rights and access to courts. Elite Mexicans dominated the agrarian sector, owning large estates. With the Roman Catholic Church still the only religion and its economic power as a source of credit for elites, conservative landowners and the Church held tremendous economic power. The largest percentage of the Mexican population was engaged in subsistence agriculture and many were only marginally engaged in market activities. Foreigners dominated commerce and trade.[67]

It was contended by Mexican liberals that the Roman Catholic Church was an obstacle to Mexico's development through its economic activities. The Church was the beneficiary of the tithe, a ten percent tax on agricultural production, until its abolition in 1833. Church properties and Indian villages produced a significant proportion of agricultural output and were outside tithe collection, while private agriculturalists' costs were higher due to the tithe. It has been argued that an impact of the tithe was in fact to keep more land in the hands of the Church and Indian villages.[68] As for the uses the Church put this ten percent of the agrarian output subject to it, it has been argued that rather being spent on "unproductive" activities that the Church had a greater liquidity that could be translated into credit for enterprises.[69]

In the first half of the nineteenth century, obstacles to industrialization were largely internal, while in the second half largely external.[70] Internal impediments to industrialization were due to Mexico's difficult topography and lack of secure and efficient transportation, remedied in the late nineteenth century by railroad construction. But the problems of entrepreneurship in the colonial period carried forward into the post-independence period. Internal tariffs, licensing for enterprises, special taxes, lack of legislation to promote joint-stock companies that protected investors, lack of enforcement to collect loans or enforce contracts, lack of patent protections, and the lack of a unified court system or legal framework to promote business made creating an enterprise a lengthy and fraught process.[71]

The Mexican government could not count on revenues from silver mining to fund its operations. The exit of Spanish merchants involved in the transatlantic trade was also a blow to the Mexican economy. The division of the former viceroyalty into separate states of a federal system, all needed a source of revenue to function meant that internal tariffs impeded trade.[72] For the weak federal government, a large source of revenue was the customs revenue on imports and exports. The Mexican government floated loans to foreign firms in the form of bonds. In 1824 the Mexican government floated a bond taken up by a London bank, B.A. Goldschmidt and Company; in 1825 Barclay, Herring, Richardson and Company of London not only loaned more money to the Mexican government, but opened a permanent office.[73] The establishment of a permanent branch of Barclay, Herring, Richardson and Co. in Mexico in 1825 and then establishment of the Banco de Londres y Sud América in Mexico set the framework for foreign loans and investment in Mexico. The Banco de Londres issued paper money for private not public debt. Paper money was a first for Mexico which had long used silver coinage.[74] After an extended civil war and foreign invasions, the late nineteenth century saw the more systematic growth of banking and foreign investment during the Porfiriato (1876–1911).

Faced with political disruptions, civil wars, unstable currency, and the constant threat of banditry in the countryside, most wealthy Mexicans invested their assets the only stable productive enterprises that remained viable: large agricultural estates with access to credit from the Catholic Church. These entrepreneurs were later accused of preferring the symbolic wealth of tangible, secure, and unproductive property to the riskier and more difficult but innovative and potentially more profitable work of investing in industry, but the fact is that agriculture was the only marginally safe investment in times of such uncertainty. Furthermore, with low per capita income and a stagnant, shallow market, agriculture was not very profitable. The Church could have loaned money for industrial enterprises, the costs and risks of starting one in the circumstances of bad transportation and lack of consumer spending power or demand meant that agriculture was a more prudent investment.[75]

However, conservative intellectual and government official Lucas Alamán founded the investment bank, Banco de Avío, in 1830 in an attempt to give direct government support to enterprise. The bank never achieved its purpose of providing capital for industrial investment and ceased to exist twelve years after its founding.[76]

Despite obstacles to industrialization in the early post-independence period, cotton textiles produced in factories owned by Mexicans date from the 1830s in the central region.[77] The Banco de Avío did loan money to cotton textile factories during its existence, so that in the 1840s, there were close to 60 factories in Puebla and Mexico City to supply the most robust consumer market in the capital.[78] In the colonial era, that region had seen the development of obrajes, small-scale workshops that wove cotton and woolen cloth.[79]

In the early republic, other industries developed on a modest scale, including glass, paper, and beer brewing. Other enterprises produced leather footwear, hats, wood-working, tailoring, and bakeries, all of which were small-scale and designed to serve domestic, urban consumers within a narrow market.[80] There were no factories to produce machines used in manufacturing, although there was a small iron and steel industry in the late 1870s before Porfirio Díaz's regime took hold after 1876.[81]

Some of the factors that impeded Mexico's own industrial development were also barriers to penetration of British capital and goods in the early republic. Small-scale manufacturing in Mexico could make a modest profit in the regions where it existed, but with high transportation costs and protective import tariffs and internal transit tariffs, there was not enough profit for British to pursue that route.[82]

Liberal reform, French intervention and Restored Republic, 1855–76

The Liberals' ouster of conservative Antonio López de Santa Anna in 1854 ushered in a major period of institutional and economic reform, but also one of civil war and foreign invasion. The Liberal Reforma via the lerdo law abolished corporations’ right to own property as corporations, a reform aimed at breaking the economic power of the Catholic Church and of Indian communities which held land as corporate communities. The Reform also mandated equality before the law, so that the special privileges or fueros that had allowed ecclesiastics and the military personnel to be tried by their own courts were abolished. The Liberals codified the Reform in the Constitution of 1857. A civil war between Liberals and Conservatives, known as the War of the Reform or the Three Years’ War was won by Liberals, but Mexico was plunged again in conflict with the government of Benito Juárez reneging on payment of foreign loans contracted by the rival conservative government. European powers prepared to intervene for repayment of the loans, but it was France with imperial ambitions that carried out an invasion and the installation of Maximilian of Habsburg as Emperor of Mexico.

The seeds of economic modernization were laid under the Restored Republic (1867–76), following the fall of the French-backed empire of Maximilian of Habsburg (1862–67). Mexican conservatives had invited Maximilian to be Mexico's monarch with the expectation that he would implement policies favorable to conservatives. Maximilian held liberal ideas and alienated his Mexican conservative supporters. The withdrawal of French military support for Maximilian, alienation of his conservative patrons, and post-Civil War support for Benito Juárez's republican government by the U.S. government precipitated Maximilian's fall. The conservatives' support for the foreign monarch destroyed their credibility and allowed the liberal republicans to implement economic policy as they saw fit after 1867 until the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910.

President Benito Juárez (1857–72) sought to attract foreign capital to finance Mexico's economic modernization. His government revised the tax and tariff structure to revitalize the mining industry, and it improved the transportation and communications infrastructure to allow fuller exploitation of the country's natural resources. The government issued contracts for construction of a new rail line northward to the United States, and in 1873 it finally completed the commercially vital Mexico City–Veracruz railroad, begun in 1837 but disrupted by civil wars and the French invasion from 1850 to 1868. Protected by high tariffs, Mexico's textile industry doubled its production of processed items between 1854 and 1877. Overall, manufacturing grew using domestic capital, though only modestly.

Mexican per capita income had fallen during the period 1800 until sometime in the 1860s, but began recovering during the Restored Republic. However, it was during the Porfiriato (the rule of General and President Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911)) that per capita incomes climbed, finally reaching again the level of the late colonial era. "Between 1877 and 1910 national income per capita grew at an annual rate of 2.3 percent—extremely rapid growth by world standards, so fast indeed that per capita income more than doubled in thirty-three years."[83]

Porfiriato, 1876–1911

When Díaz first came to power, the country was still recovering from a decade of civil war and foreign intervention, and the country was deeply in debt. Díaz saw investment from the United States and Europe as a way to build a modern and prosperous country.[84] During the Porfiriato, Mexico underwent rapid but highly unequal growth. The phrase "order and progress" of the Díaz regime was shorthand for political order laying the groundwork for progress to transform and modernize Mexico on the model of Western Europe or the United States. The apparent political stability of the regime created a climate of trust for foreign and domestic entrepreneurs to invest in Mexico's modernization.[85] Rural banditry, which had increased following the demobilization of republican force, was suppressed by Díaz, using the rural police force, rurales, often transporting them and their horses on trains. Other factors promoting a better economic situation were the elimination of local customs duties that had hindered domestic trade were abolished.

Changes in fundamental legal principles of ownership during the Porfiriato had a positive effect on foreign investors. During Spanish rule, the crown controlled subsoil rights of its territory so that silver mining, the motor of the colonial economy, was controlled by the crown with licenses to mining entrepreneurs was a privilege not a right. The Mexican government changed the law to giving absolute subsoil rights to property owners. For foreign investors, protection of their property rights meant that mining and oil enterprises became much more attractive investments.

The earliest and most far reaching foreign investment was in the creation of a railway network. Railroads dramatically decreased transportation costs so that heavy or bulky products could be exported to Mexico's Gulf Coast ports as well as rail links on the U.S. border. The railway system expanded from a line from Mexico City to the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz to create an entire network of railways that encompassed most regions of Mexico.[86] Railroads were initially owned almost exclusively by foreign investors, expanded from 1,000 kilometers to 19,000 kilometers of track between 1876 and 1910. Railways have been termed a "critical agent of capitalist penetration,"[87] Railways linked areas of the country that previously suffered from poor transportation capability, that is, they could produce goods, but could not get them to market.[88] When British investors turned their attention to Mexico, they primarily made investments in railways and mines, sending both money and engineers and skilled mechanics.[89]

.jpg)

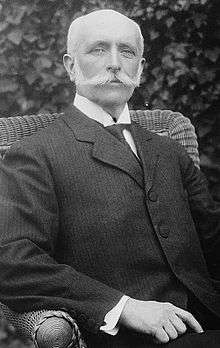

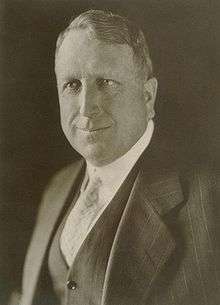

The development of the petroleum industry in Mexico on the Gulf Coast dates from the late nineteenth century. Two prominent foreign investors were Weetman Pearson, who was later knighted by the British crown,[90] and Edward L. Doheny, as well as Rockefeller's Standard Oil. Oil has been an important contributor to the Mexican economy as well as an ongoing political issue, since early development was entirely in the hands of foreigners. Economic nationalism played the key role in the Mexican oil expropriation of 1938.

Mining silver continued as an enterprise, but copper emerged as a valuable mining resource as electricity became an important technological innovation. The creation of telephone and telegraph networks meant large-scale demand for copper wiring. Individual foreign entrepreneurs and companies purchased mining sites. Among the owners were Amalgamated Copper Company, American Telephone and Telegraph, American Smelting and Refining Company, and Phelps Dodge.[91] The Greene Consolidated Copper Company became infamous in Mexico when its Cananea mine workers went on strike in 1906 and the rurales in Mexico and Arizona Rangers suppressed it.

._Mexico_(21605591919).jpg)

Northern Mexico had the greatest concentration of mineral resources as well as closest proximity to a major market for foodstuffs, the United States.[92] As the railroad system improved, and as the population grew in the western U.S., large-scale commercial agriculture became viable. From the colonial period onward, the North had developed huge landed estates devoted mainly to cattle ranching. With the expansion of the rail network northward and with the Mexican government's policies of surveying land and clearing land titles, commercial agriculture expanded enormously, especially along the U.S.-Mexico border. Both U.S. and Mexican entrepreneurs began investing heavily in modernized large-scale agricultural estates along the railroad lines of the north. The family of future Mexican president Francisco I. Madero developed successful enterprises in the Comarca Lagunera region, which spans the states of Coahuila and Durango, where cotton was commercially grown. Madero sought to interest fellow large landowners in the region in pushing for the construction of a high dam to control periodic flooding along the Nazas river, and increase agricultural production there. One was constructed in the post-revolutionary period.[93] The bilingual son of a U.S. immigrant to Mexico and the niece of the powerful Creel-Terrazas family of Chihuahua, Enrique Creel became a banker and intermediary between foreign investors and the Mexican government. As a powerful politician and landowner, Creel "became one of the most hated symbols of the Porfirian regime."[94]

.jpg)

Mexico was not a favored destination for European immigrants the way the United States, Argentina, and Canada were in the nineteenth century, creating expanded work forces there. Mexico's population in 1800 at 6 million was a million larger than that of the young U.S. republic, but in 1910 Mexico's population was 15 million while that of the U.S. was 92 million. Lack of slow natural increase and higher death rates coupled with lack of immigration meant that Mexico had a much smaller labor force in comparison.[95] Americans moved to Mexico in the largest numbers, but most to pursue ranching and farming themselves, and were the largest group on foreign nationals in Mexico. In 1900, there were only 2800 British citizens living in Mexico, 16,000 Spaniards, 4,000 French, and 2,600 Germans.[89] Foreign enterprises employed significant numbers of foreign workers, especially in skilled, higher paying positions keeping Mexicans in semi-skilled positions with much lower pay. The foreign workers did not generally know Spanish, so business transactions were done in the foreign industrialists' language. The cultural divide extended to religious affiliation (many were Protestants) and different attitudes "about authority and justice."[96] There were few foreigner workers in the central Mexican textile industry, but many in mining and petroleum, where Mexicans had little or no experience with advanced technologies.[97]

.jpg)

Mexican entrepreneurs also created large enterprises, many of which were vertically integrated. Some of these include steel, cement, glass, explosives, cigarettes, beer, soap, cotton and wool textiles, and paper.[98] Yucatán underwent an agricultural boom with the creation of large-scale henequen (sisal) haciendas. Yucatán's capital of Mérida saw many elites build mansions based on the fortunes they made in henequen.[99] The financing of Mexican domestic industry was accomplished through a small group of merchant-financiers, who could raise the capital for high start up costs of domestic enterprises, which included the importation of machinery. Although industries were created, the national market was yet to be built so that enterprises ran inefficiently well below their capacity.[100] Overproduction was a problem since even a minor downturn in the economy meant the consumers with little buying power had to choose necessities over consumer-goods.

Under the surface of all this apparent economic prosperity and modernization, popular discontent was reaching the boiling point. The economic-political elite scarcely noticed the country's widespread dissatisfaction with the political stagnation of the Porfiriato, the increased demands for worker productivity during a time of stagnating or decreasing wages and deteriorating work conditions, the repression of worker's unions by the police and army, and the highly unequal distribution of wealth. When a political opposition to the Porfirian regime developed in 1910, following Díaz's initial statement that he would not run again for the presidency in 1910 and then reneging, there was considerable unrest.

As industrial enterprises grew in Mexico, workers organized to assert their rights. Strikes occurred in the mining industry, most notably at the U.S.-owned Cananea Consolidated Copper Company in 1906, in which Mexican workers protested that they were paid half what U.S. nations earned for the same work. U.S. marshals and citizens crossed from Arizona to Sonora to suppress the strike, resulting in 23 deaths. The violent incident was evidence that there was labor unrest in Mexico, something the Díaz regime sought to deny. The enforcement of labor discipline by U.S. nationals was publicly seen as a violation of Mexican sovereignty, but there were no consequences for the government of Sonora for permitting the foreigners' actions. The Díaz regime accused the radical Mexican Liberal Party of fomenting the strike. The significance of the strike is disputed, but one scholar considers it "an important benchmark for the Porfirian labor movement as well as the regime. It raised the social question in a dramatic fashion, and at the same time fused it with Mexican nationalism.[101] In 1907, workers at the French-owned Río Blanco textile factory engaged in a dispute after being locked out from their factory. Díaz sent the Mexican army to suppress the action, resulting in loss of life of an unknown number of Mexicans. Before 1909 most workers were reformist and not anti-Díaz, but did seek government intervention on their behalf against foreign owners' unfair practices, particularly regarding wage differentials.[102]

Signs of economic prosperity were apparent in the capital. The Mexican stock exchange was founded in 1895, with headquarters on Plateros Street (now Madero Street) in Mexico City, trading in commodities and stocks. With increasing political stability and economic growth, Mexico’s urban populations had more disposable income and spent it on consumer goods. In Mexico City, several French entrepreneurs established department stores stocked with goods form the global economy. Such enterprises promoting consumer culture were taking hold in Paris (the Bon Marché) and London (Harrod’s), catering to elite urban consumers. They used advertising and innovative ways of displaying and selling goods. Female clerks catered to customers. In Mexico City, the Palacio de Hierro was one example, with its five-story building in downtown was constructed of iron. The flourishing of such stores was a signal of Mexico’s modernity and participation in the transnational cosmopolitanism of the era. French immigrants from the Barcelonette region of France established the vast majority of the department stores in Porfirian Mexico. These immigrants had dominated the retail apparel market for increasingly fashion-conscious elites. Two of the biggest enterprises adopted the business model of the joint stock company (sociedad anónima, or S.A.) and were listed on the Mexican stock exchange. Enterprises sourced their merchandise from abroad, using British, German, Belgian, and Swiss suppliers, but they also sold textiles made in their own factories in Mexico, creating a level of vertical integration. The Barcelonettes, as they were called, also innovated by using hydroelectric power in some of their textile factories, and supplied some surrounding communities.[103]

Gallery

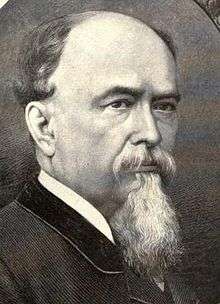

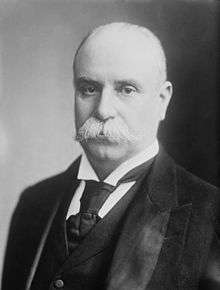

José Yves Limantour, Díaz's minister of finance, 1893–1911

José Yves Limantour, Díaz's minister of finance, 1893–1911 Manuel Romero Rubio, Científico and Díaz's father-in-law

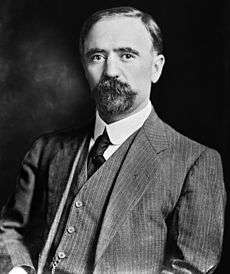

Manuel Romero Rubio, Científico and Díaz's father-in-law Enrique Creel, northern banker and landowner, key figure in the Díaz regime

Enrique Creel, northern banker and landowner, key figure in the Díaz regime Francisco I. Madero, wealthy landowner who challenged Díaz for the presidency

Francisco I. Madero, wealthy landowner who challenged Díaz for the presidency Weetman Pearson, a Briton who made a fortune during the Porfiriato in railroads and oil

Weetman Pearson, a Briton who made a fortune during the Porfiriato in railroads and oil Edward L. Doheny, U.S. investor in Mexican oil

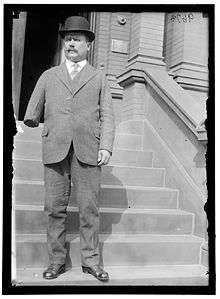

Edward L. Doheny, U.S. investor in Mexican oil William Randolph Hearst, whose family owned millions of acres of land in northern Mexico

William Randolph Hearst, whose family owned millions of acres of land in northern Mexico

Era of the Mexican Revolution, 1910–20

.jpg)

The outbreak of the Revolution in 1910 began as a political crisis over presidential succession and exploded into civil wars of movement in northern Mexico and guerrilla warfare in the peasant centers near Mexico City. The former working relationship between the Mexican government and foreign and domestic enterprises was nearing an end with the fall of the Díaz government, producing uncertainty for businesses. The upstart challenger to Porfirio Díaz in the 1910 election, Francisco I. Madero, was from a very wealthy, estate-owning family in northern Mexico. After the fraudulent election, Madero issued the Plan of San Luis Potosí, calling for a revolt against Díaz. In his plan he made the vague promise to return stolen village lands, making Madero appear sympathetic to the peasantry and potentially bringing about land reform. For Mexican and foreign large-land owners, Madero's vague promise was a threat to their economic interests. For the peasants in Morelos, a sugar-growing area close to Mexico City, Madero's slowness to make good on his promise to restore village lands prompted a revolt against the government. Under the Plan of Ayala, sweeping land reform was the core of their demands. Earlier, the demands by the Liberal Party of Mexico (PLM) articulated a political and economic agenda, much of which was incorporated into the Constitution of 1917.

American-owned enterprises especially were targets during revolutionary violence, but there was generally loss of life and property damage in areas of conflict. Revolutionaries confiscated haciendas with livestock, machinery, and buildings. Railways used for troop movements in northern Mexico were hard hit by the destruction of tracks, bridges, and rolling stock. Significantly, the Gulf Coast petroleum installations were not damaged. They were a vital source of revenue for the Constitutionalist faction that was ultimately victorious in the decade-long civil conflict. The promulgation of the 1917 Constitution of 1917 was one of the first acts of the faction named for the Constitution of 1857.

The Constitutionalist faction of Mexico's North was victorious in 1915-16. Northern revolutionaries were not sympathetic to demands by peasants in central Mexico seeking the return if village land a reversion to small-scale Agriculture. The Constitutionalists mobilized organized labor against the peasant uprising in Morelos under Emiliano Zapata. Urban labor needed cheap foodstuffs and sought the expansion of the industrial sector versus subsistence peasant agriculture. Labor's support was rewarded in the new constitution. The drafting of that constitution was major outcome of the nearly decade-long conflict. Organized labor was a big winner, with Article 123 enshrining in the constitution basic worker rights, such as the right to organize and strike, the eight-hour day, and safe working conditions. Organized labor could no longer be simply suppressed by the industrialists or the Mexican state. Although Mexican and foreign industrialists now had to contend with a new legal framework, the Revolution did not, in fact, destroy the industrial sector, either its factories, extractive facilities, or its industrial entrepreneurs, so that once the fighting stopped in 1917, production resumed.[105]

Article 27 of the Constitution empowered the state to expropriate private holdings if deemed in the national interest and returned subsoil rights to the state. It enshrined the right of the state could expropriate land and redistribute it to peasant cultivators. Although there could be a major roll back of changes in land tenure, the leader of the Constitutionalists and now President, Venustiano Carranza, was both a politician and large land owner, who was unwilling implement land reform. The state's power regarding subsoil rights meant that the mining and petroleum industries that were developed and owned by foreign industrialists now had less secure title to their enterprises. The industrial sector of Mexico escaped the destruction of revolutionary violence and many Mexican and foreign industrialists remained in Mexico, but the uncertainty and risk of new investments in Mexican industry meant that it did not expand in the immediate post-Revolutionary period.[106] An empowered labor movement with constitutionally guaranteed rights was a new factor industrialists also had to deal with. However, despite the protections of organized labor's rights to fair wages and working conditions, the constitution restricted laborers' ability to emigrate to the U.S. to work. It "required each Mexican to have a labor contract signed by municipal authories and the consulate of the country where they intended to work."[107] Since "U.S. law prohibited offering contracts to foreign laborers before they entered the United States," Mexicans migrating without a permission from Mexico did so illegally.[108]

Consolidating the Revolution and the Great Depression, 1920-40

In 1920, Sonoran general Alvaro Obregón was elected president of Mexico. A key task was to secure diplomatic recognition from the United States. The American-Mexican Claims Commission was established to deal with claims by Americans for property-loss during the Revolution. Obregón also negotiated the Bucareli Treaty with the United States, an important step in securing recognition. Concessions made to foreign oil during the Porfiriato were a particularly difficult matter in the post-Revolutionary period, but General and President Alvaro Obregón negotiated a settlement in 1923, the Bucareli Treaty, that guaranteed petroleum enterprises already built in Mexico. It also settled some claims between the U.S. and Mexico stemming from the Revolution. The treaty had an important impact for the Mexican government, since it paved the way for U.S. recognition of Obregón's government. The agreement not only normalized diplomatic relations, but also opened the way for U.S. military aid to the regime and gave Obregón the means to suppress a rebellion. As the Porfiriato had demonstrated, a strong government that could maintain order paved the way for other national benefits; however, the Constitution of 1917 sought to enshrine rights of groups that suffered under that authoritarian regime.

General and President Plutarco Elías Calles succeeded Obregón in the presidency; he was another of the revolutionary generals who then became president of Mexico. An important economic achievement of the Calles administration was the 1925 founding of the Banco de México, that became the first permanent government bank (following the nineteenth-century failure of the Banco de Avío). Although this was an important economic achievement, Calles enforced the anticlerical articles of the Constitution of 1917, prompting a major outbreak of violence in the Cristero rebellion of 1926–29. Such violence in the center of the country killed tens of thousands and prompted many living in the region to migrate to the United States. For the United States, the situation was worrisome, since U.S. industrialists continued to have significant investments in Mexico and the U.S. government had a long-term desire for peace along its long southern border with Mexico. The U.S. ambassador to Mexico, Dwight Morrow, a former Wall Street banker, brokered an agreement in 1929 between the Mexican government and the Roman Catholic Church, which restored better conditions for economic development.

The Mexican political system was again seen as fragile when in 1928 a religious fanatic assassinated president-elect Obregón, who would have returned to the presidency after a four-year hiatus. Calles stepped in to form in 1929 the Partido Nacional Revolucionario, the precursor to the Institutional Revolutionary Party, helped stabilize the political and economic system, creating a mechanism to manage conflicts and set the stage for more orderly presidential elections. Later that year, the U.S. stock market crashed and the Mexican economy suffered as the worldwide Great Depression took hold. It had already slowed in the 1920s, with investor pessimism and the fall of Mexican exports as well as capital flight. Even before the Great Crash of the U.S. stock market in 1929, Mexican export incomes fell between 1926 and 1928 from $334 million to $299 million (approximately 10%) and then fell even further as the Depression took hold, essentially collapsing.[109] In 1932, GDP dropped 16%, after drops in 1927 of 5.9%, in 1928 5.4%, and 7.7%, such that there was a drop in GDP of 30.9% in a six-year period.[110][111]

The Great Depression brought Mexico a sharp drop in national income and internal demand after 1929. A complicating factor for Mexico-United States relations in this period was forced Mexican repatriation of undocumented Mexican workers in the U.S. at the time.[112][113] The largest sector of the Mexican economy remained subsistence agriculture so that these fluctuations in the world market and the Mexican industrial sector did not affect all sectors of Mexico equally.

In the mid-1930s, Mexico's economy started to recover under the General and President Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–40), which initiated a new phase of industrialization in Mexico.[114] In 1934, Cárdenas created the National Finance Bank(Nacional Financiera SA (Nafinsa)).[115] as a "semi-private finance company to sell rural real estate" but its mandate was expanded during the term of Cárdenas's successor, Manuel Avila Camacho term to include any enterprise in which the government had an interest.[116] An important achievement of the Cárdenas presidency was "the restoration of social peace"[117] achieved in part by not exacerbating the long simmering post-revolutionary conflict between the Mexican state and the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico, extensive redistribution of land to the peasantry, and re-organizing the party originally created by Plutarco Elías Calles into one with sectoral representation of workers, peasants, the popular sector, and the Mexican army. The Partido Revolucionario Mexicana created the mechanism to manage conflicting economic and political groups and manage national elections.

Education had always been a key factor in the nation's development, with liberals enshrining secular, public education in the Constitution of 1857 and the Constitution of 1917 to exclude and counter the Roman Catholic Church from its long-standing role in education. Cárdenas founded the Instituto Politécnico Nacional in 1936 in northern Mexico City, to train professional scientists and engineers to forward Mexico's economic development. The National Autonomous University of Mexico traditionally trained lawyers and doctors, and in its colonial incarnation, it was a religiously affiliated university. UNAM has continued to be the main university for aspiring politicians to attend, at least as undergraduates, but the National Polytechnic Institute marked a significant step in reforming Mexican higher education.

The railroads had been nationalized in 1929 and 1930 under Cárdenas's predecessors, but his nationalization of the Mexican petroleum industry was a major move in 1938, which created Petroleos Mexicanos or PEMEX. Cárdenas also nationalized the paper industry, whose best-selling product was newsprint. In Mexico the paper industry was controlled by a single firm, the San Rafael y Anexas paper company. Since there was no well-developed capital market in Mexico ca. 1900, a single company could dominate the market. But in 1936, Cárdenas considered newsprint a strategic company and nationalized it. By nationalizing it, a company with poor prospects for flourishing could continue via government support.[118] During the 1930s, agricultural production also rose steadily, and urban employment expanded in response to rising domestic demand. The government offered tax incentives for production directed toward the home market. Import-substitution industrialization began to make a slow advance during the 1930s, although it was not yet official government policy.

To foster industrial expansion, the administration of Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940–46) in 1941 reorganized the National Finance Bank. During his presidency, Mexico's economy recovered from the Depression and entered a period of sustained growth, known as the Mexican Miracle.

World War II and the Mexican miracle, 1940–1970

Mexico's inward-looking development strategy produced sustained economic growth of 3 to 4 percent and modest 3 percent inflation annually from the 1940s until the 1970s. This growth was sustained by the government's increasing commitment to primary education for the general population from the late 1920s through the 1940s. The enrollment rates of the country's youth increased threefold during this period;[119] consequently when this generation was employed by the 1940s their economic output was more productive. Additionally, the government fostered the development of consumer goods industries directed toward domestic markets by imposing high protective tariffs and other barriers to imports. The share of imports subject to licensing requirements rose from 28 percent in 1956 to an average of more than 60 percent during the 1960s and about 70 percent in the 1970s. Industry accounted for 22 percent of total output in 1950, 24 percent in 1960, and 29 percent in 1970. The share of total output arising from agriculture and other primary activities declined during the same period, while services stayed constant. The government promoted industrial expansion through public investment in agricultural, energy, and transportation infrastructure. Cities grew rapidly during these years, reflecting the shift of employment from agriculture to industry and services. The urban population increased at a high rate after 1940 (see Urban Society, ch. 2).

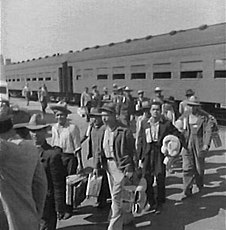

Although growth of the urban labor force exceeded even the growth rate of industrial employment, with surplus workers taking low-paying service jobs, many Mexican laborers migrated to the United States where wages were higher. During World War II, Mexico-United States relations had improved significantly from the previous three decades. The Bracero Program was set up with orderly migration flows were regulated by both governments. However. many Mexicans could not qualify for the program and migrated north illegally, without permission from their own government and without sanction from the U.S. authorities.[120] In the post-war period as the U.S. economy boomed and as Mexico's entered a phase of rapid industrialization, the U.S. and Mexico cooperated closely on illegal border crossings by Mexicans. For the Mexican government, this loss of labor was "a shameful exposure of the failure of the Mexican Revolution to provide economic well-being for many of Mexico's citizens, but it also drained the country of one of its greatest natural resources, a cheap and flexible labor supply."[121] The U.S. and Mexico cooperated closely to stop the flow, including the 1954 program called Operation Wetback.

In the years following World War II, President Miguel Alemán Valdés's (1946–52) full-scale import-substitution program stimulated output by boosting internal demand. The government raised import controls on consumer goods but relaxed them on capital goods, which it purchased with international reserves accumulated during the war. The government spent heavily on infrastructure. By 1950 Mexico's road network had expanded to 21,000 kilometers, of which some 13,600 were paved. Large-scale dam building for hydroelectric power and flood control were initiated, most prominently the Papaloapan Project in southern Mexico.[122] In recent years, there has been a re-evaluation of such infrastructure projects, particularly their negative impact on the environment.[123]

Mexico's strong economic performance continued into the 1960s, when GDP growth averaged about 7 percent overall and about 3 percent per capita. Consumer price inflation averaged only 3 percent annually. Manufacturing remained the country's dominant growth sector, expanding 7 percent annually and attracting considerable foreign investment. Mining grew at an annual rate of nearly 4 percent, trade at 6 percent, and agriculture at 3 percent. By 1970 Mexico had diversified its export base and become largely self-sufficient in food crops, steel, and most consumer goods. Although its imports remained high, most were capital goods used to expand domestic production.

Deterioration in the 1970s

Although the Mexican economy maintained its rapid growth during most of the 1970s, it was progressively undermined by fiscal mismanagement and by a poor export industrial sector and a resulting sharp deterioration of the investment climate. The GDP grew more than 6 percent annually during the administration of President Luis Echeverría Álvarez (1970–76), and at about a 6 percent rate during that of his successor, José López Portillo y Pacheco (1976–82). But economic activity fluctuated wildly during the decade, with spurts of rapid growth followed by sharp depressions in 1976 and 1982.

Fiscal profligacy combined with the 1973 oil shock to exacerbate inflation and upset the balance of payments. Moreover, President Echeverría's leftist rhetoric and actions—such as abetting illegal land seizures by peasants—eroded investor confidence and alienated the private sector. The balance of payments disequilibrium became unmanageable as capital flight intensified, forcing the government in 1976 to devalue the peso by 58 percent. The action ended Mexico's twenty-year fixed exchange rate. Mexico accepted an IMF adjustment program and received financial backing from the United States. According to a 2017 study, "Key US and Mexican officials recognized that an IMF program of currency devaluation and austerity would probably fail in its stated objective of reducing Mexico's balance of payments deficit. Nevertheless, US Treasury and Federal Reserve officials, fearing that a Mexican default might lead to bank failures and subsequent global financial crisis, intervened to an unprecedented degree in the negotiations between the IMF and Mexico. The United States offered direct financial support and worked through diplomatic channels to insist that Mexico accept an IMF adjustment program, as a way of bailing out US banks. Mexican president Luis Echeverría's administration consented to IMF adjustment because officials perceived it as the least politically costly option among a range of alternatives."[124]

Although significant oil discoveries in 1976 allowed a temporary recovery, the windfall from petroleum sales also allowed continuation of Echeverría's destructive fiscal policies. In the mid-1970s, Mexico went from being a net importer of oil and petroleum products to a significant exporter. Oil and petrochemicals became the economy's most dynamic growth sector. Rising oil income allowed the government to continue its expansionary fiscal policy, partially financed by higher foreign borrowing. Between 1978 and 1981, the economy grew more than 8 percent annually, as the government spent heavily on energy, transportation, and basic industries. Manufacturing output expanded modestly during these years, growing by 8.2 percent in 1978, 9.3 percent in 1979, and 8.2 percent in 1980.

This renewed growth rested on shaky foundations. Mexico's external indebtedness mounted, and the peso became increasingly overvalued, hurting non-oil exports in the late 1970s and forcing a second peso devaluation in 1980. Production of basic food crops stagnated and the population increase was skyrocketing, forcing Mexico in the early 1980s to become a net importer of foodstuffs. The portion of import categories subject to controls rose from 20 percent of the total in 1977 to 24 percent in 1979. The government raised tariffs concurrently to shield domestic producers from foreign competition, further hampering the modernization and competitiveness of Mexican industry.

1982 crisis and recovery

The macroeconomic policies of the 1970s left Mexico's economy highly vulnerable to external conditions. These turned sharply against Mexico in the early 1980s, and caused the worst recession since the 1930s, with the period known in Mexico as La Década Perdida, "the lost decade", i.e., of economic growth. By mid-1981, Mexico was beset by falling oil prices, higher world interest rates, rising inflation, a chronically overvalued peso, and a deteriorating balance of payments that spurred massive capital flight. This disequilibrium, along with the virtual disappearance of Mexico's international reserves—by the end of 1982 they were insufficient to cover three weeks' imports—forced the government to devalue the peso three times during 1982. The devaluation further fueled inflation and prevented short-term recovery. The devaluations depressed real wages and increased the private sector's burden in servicing its dollar-denominated debt. Interest payments on long-term debt alone were equal to 28 percent of export revenue. Cut off from additional credit, the government declared an involuntary moratorium on debt payments in August 1982, and the following month it announced the nationalization of Mexico's private banking system.

By late 1982, incoming President Miguel de la Madrid reduced public spending drastically, stimulated exports, and fostered economic growth to balance the national accounts. Recovery was slow to materialize, however. The economy stagnated throughout the 1980s as a result of continuing negative terms of trade, high domestic interest rates, and scarce credit. Widespread fears that the government might fail to achieve fiscal balance and have to expand the money supply and raise taxes deterred private investment and encouraged massive capital flight that further increased inflationary pressures. The resulting reduction in domestic savings impeded growth, as did the government's rapid and drastic reductions in public investment and its raising of real domestic interest rates to deter capital flight.