Rum-running

Rum-running or bootlegging is the illegal business of transporting (smuggling) alcoholic beverages where such transportation is forbidden by law. Smuggling usually takes place to circumvent taxation or prohibition laws within a particular jurisdiction. The term rum-running is more commonly applied to smuggling over water; bootlegging is applied to smuggling over land.

It is believed that the term bootlegging originated during the American Civil War, when soldiers would sneak liquor into army camps by concealing pint bottles within their boots or beneath their trouser legs. Also, according to the PBS documentary Prohibition, the term bootlegging was popularized when thousands of city dwellers sold liquor from flasks they kept in their boot legs all across major cities and rural areas.[1][2] The term rum-running most likely originated at the start of Prohibition in the United States (1920–1933), when ships from Bimini in the western Bahamas transported cheap Caribbean rum to Florida speakeasies. But rum's cheapness made it a low-profit item for the rum-runners, and they soon moved on to smuggling Canadian whisky, French champagne, and English gin to major cities like New York City, Boston, and Chicago, where prices ran high. It was said that some ships carried $200,000 in contraband in a single run.

History

It was not long after the first taxes were implemented on alcoholic beverages that someone began to smuggle alcohol. The British government had "revenue cutters" in place to stop smugglers as early as the 16th century. Pirates often made extra money running rum to heavily taxed colonies. There were times when the sale of alcohol was limited for other reasons, such as laws against sales to American Indians in the Old West and Canada West or local prohibitions like the one on Prince Edward Island between 1901 and 1948.

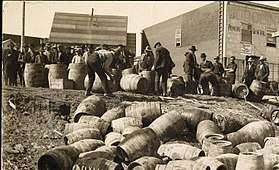

Industrial-scale smuggling flowed both ways across the Canada–United States border at different points in the early twentieth century, largely between Windsor, Ontario and Detroit, Michigan. Although Canada never had true nationwide prohibition, the federal government gave the provinces an easy means to ban alcohol under the War Measures Act (1914), and most provinces and the Yukon Territory already had enacted prohibition locally by 1918 when a regulation issued by the federal cabinet banned the interprovincial trade and importation of liquor. National prohibition in the United States did not begin until 1920, though many states had statewide prohibition before that. For the two-year interval, enough American liquor entered Canada illegally to undermine support for prohibition in Canada, so it was slowly lifted, beginning with Quebec and Yukon in 1919 and including all the provinces but Prince Edward Island by 1930. Additionally, Canada's version of prohibition had never included a ban on the manufacture of liquor for export. Soon the black-market trade was reversed with Canadian whisky and beer flowing in large quantities to the United States. Again, this illegal international trade undermined the support for prohibition in the receiving country, and the American version ended (at the national level) in 1933.

One of the most famous periods of rum-running began in the United States when Prohibition began on January 16, 1920, when the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect. This period lasted until the amendment was repealed with ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment on December 5, 1933.

At first, there was much action on the seas, but after several months, the Coast Guard began reporting decreased smuggling activity. This was the start of the Bimini–Bahamas rum trade and the introduction of Bill McCoy.

With the start of prohibition, Captain McCoy began bringing rum from Bimini and the rest of the Bahamas into south Florida through Government Cut. The Coast Guard soon caught up with him, so he began to bring the illegal goods to just outside U.S. territorial waters and let smaller boats and other captains, such as Habana Joe, take the risk of bringing it to shore.

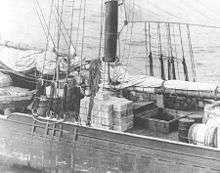

The rum-running business was very good, and McCoy soon bought a Gloucester knockabout schooner named Arethusa at auction and renamed her Tomoka. He installed a larger auxiliary, mounted a concealed machine gun on her deck, and refitted the fish pens below to accommodate as much contraband as she could hold. She became one of the most famous of the rum-runners, along with his two other ships hauling mostly Irish and Canadian whiskey as well as other fine liquors and wines to ports from Maine to Florida.

In the days of rum running, it was common for captains to add water to the bottles to stretch their profits or to re-label it as better goods. Often, cheap sparkling wine would become French champagne or Italian Spumante; unbranded liquor became top-of-the-line name brands. McCoy became famous for never adding water to his booze and selling only top brands. Although the phrase appears in print in 1882, this is one of several folk etymologies for the origin of the term "The real McCoy".

On November 15, 1923, McCoy and Tomoka encountered the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Seneca just outside U.S. territorial waters. A boarding party attempted to board, but McCoy chased them off with the machine gun. Tomoka tried to run, but Seneca placed a shell just off her hull, and William McCoy surrendered his ship and cargo.

The Rum Row

McCoy is credited with the idea of bringing large boats just to the edge of the three-mile (4.8 km) limit of U.S. jurisdiction and selling his wares there to "contact boats", local fishermen, and small boat captains. The small, quick boats could more easily outrun Coast Guard ships and could dock in any small river or eddy and transfer their cargo to a waiting truck. They were also known to load float planes and flying boats. Soon others were following suit, and the three-mile (4.8 km) limit became known as "Rum Line" with the ships waiting called "Rum row". The Rum Line was extended to a 12-mile (19.3 km) limit by an act of the United States Congress on April 21, 1924, which made it harder for the smaller and less seaworthy craft to make the trip.[3]

Rum Row was not the only front for the Coast Guard. Rum-runners often made the trip through Canada via the Great Lakes and the Saint Lawrence Seaway and down the west coast to San Francisco and Los Angeles. Rum-running from Canada was also an issue, especially throughout prohibition in the early 1900s. There was a high number of distilleries in Canada, one of the most famous being Hiram Walker who developed Canadian Club Whisky. The French islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, located south of Newfoundland, were an important base used by well-known smugglers, including Al Capone, Savannah Unknown, and Bill McCoy. The Gulf of Mexico also teemed with ships running from Mexico and the Bahamas to Galveston, Texas, the Louisiana swamps, and Alabama coast. By far the biggest Rum Row was in the New York/Philadelphia area off the New Jersey coast, where as many as 60 ships were seen at one time. One of the most notable New Jersey rum runners was Habana Joe, who could be seen at night running into remote areas in Raritan Bay with his flat-bottom skiff for running up on the beach, making his delivery, and speeding away.

With that much competition, the suppliers often flew large banners advertising their wares and threw parties with prostitutes on board their ships to draw customers. Rum Row was completely lawless, and many crews armed themselves not against government ships but against the other rum-runners, who would sometimes sink a ship and hijack its cargo rather than make the run to Canada or the Caribbean for fresh supplies.

The ships

At the start, the rum-runner fleet consisted of a ragtag flotilla of fishing boats, such as the schooner Nellie J. Banks, excursion boats, and small merchant craft. As prohibition wore on, the stakes got higher and the ships became larger and more specialized. Converted fishing ships like McCoy's Tomoka waited on Rum Row and were soon joined by small motor freighters custom-built in Nova Scotia for rum running, with low, grey hulls, hidden compartments, and powerful wireless equipment. Examples include the Reo II. Specialized high-speed craft were built for the ship-to-shore runs. These high-speed boats were often luxury yachts and speedboats fitted with powerful aircraft engines, machine guns, and armor plating. Often, builders of rum-runners' ships also supplied Coast Guard vessels, such as Fred and Mirto Scopinich's Freeport Point Shipyard.[4] Rum-runners often kept cans of used engine oil handy to pour on hot exhaust manifolds in case a screen of smoke was needed to escape the revenue ships.

On the government's side, the rum chasers were an assortment of patrol boats, inshore patrol, and harbor cutters. Most of the patrol boats were of the "six-bit" variety: 75-foot craft with a top speed of about 12 knots. There was also an assortment of launches, harbor tugs, and miscellaneous small craft.

The rum-runners were definitely faster and more maneuverable. Add to that the fact that a rum-running captain could make several hundred thousand dollars a year. In comparison, the Commandant of the Coast Guard made just $6,000 annually, and seamen made $30/week. These huge rewards meant the rum-runners were willing to take big risks. They ran without lights at night and in fog, risking life and limb. Often, the shores were littered with bottles from a rum-runner who sank after hitting a sandbar or a reef in the dark of high speed.

The Coast Guard relied on hard work, reconnaissance, and big guns to get their job done. It was not uncommon for rum-runners' ships to be sold at auction shortly after a trial — often right back to the original owners. Some ships were captured three or four times before they were finally sunk or retired. In addition, the Coast Guard had other duties and often had to let a rum-runner go in order to assist a sinking vessel or handle another emergency.[5]

Alcohol smuggling today

For multiple reasons (including the avoidance of taxes and minimum purchase prices), alcohol smuggling is still a worldwide concern.

In the United States, the smuggling of alcohol did not end with the repeal of prohibition. In the Appalachian United States, for example, the demand for moonshine was at an all-time high in the 1920s, but an era of rampant bootlegging in dry areas continued into the 1970s.[6] Although the well-known bootleggers of the day may no longer be in business, bootlegging still exists, even if on a smaller scale. The state of Virginia has reported that it loses up to $20 million a year from illegal whiskey smuggling.[7]

The Government of the United Kingdom fails to collect an estimated £900 million in taxes due to alcohol smuggling activities.[8]

Absinthe was smuggled into the United States until it was legalized in 2007.[9] Cuban rum is also sometimes smuggled into the United States, circumventing the embargo in existence since 1960.[10]

See also

- Alcohol laws of the United States

- Alcohol in Colonial America

- American gangsters during the 1920s

- American Whiskey Trail

- Bootleggers and Baptists

- Bureau of Prohibition

- Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF)

- Dry state

- Govenlock, Saskatchewan

- Iron law of prohibition

- Izzy Einstein and Moe Smith

- Moonshine

- Nellie J. Banks

- Organized crime

- Prohibition

- Prohibition in Canada

- Prohibition in the United States

- Repeal of Prohibition

- Shebeen

- United States Customs Service

- Volstead Act

- Webb–Kenyon Act

References

- Mary Murphy. "Bootlegging Mothers and Drinking Daughters: Gender and Prohibition in Butte Montana." American Quarterly, Vol 46, No 2, 1994.

- Prohibition (miniseries), Episode 1, "A Nation of Drunkards". Directed by Ken Burns & Lynn Novick. Distributed by PBS.

- Kelley, Katie (October 1, 2014). "Episode 28 Rum Runner". A History of Central Florida Podcast. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- History Alive:Rumrunners, Moonshiners and Bootleggers Trivia and Quotes (television). History Channel. February 23, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- "X-boats War On Smugglers" Popular Mechanics, August 1932

- Peine, Emelie K.; Schafft, Kai A. (2012). "Moonshine, Mountaineers, and Modernity: Distilling Cultural History in the Southern Appalachian Mountains". Journal of Appalachian Studies. 18: 98.

- "Moonshine in Virginia creates loss of $20 million: Havocscope Black Markets".

- "Alcohol smuggling in the United Kingdom: Havocscope Black Markets".

- Asimov, Eric (May 13, 2009). "Absinthes to Go Mad Over". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Swift, Aisling (May 24, 2008). "Two charged with smuggling Cuban rum, cigars into Southwest Florida". Naples Daily News. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

Further reading

- Allen, Everett S. The Black Ships: Rumrunners of Prohibition. Little, Brown. 1979. ISBN 0-316-03258-1.

- Carse, Robert. Rum Row.

- Cohen, Daniel. Prohibition: America Makes Alcohol Illegal. Millbrook Press. 1995.

- Frew, David. Prohibition and Rum Running on Lake Erie (The Lake Erie Quadrangle Shipwreck Series, Book 4) Erie County Historical Society; 1ST edition (2006) ISBN 1-883658-48-9.

- Gervais, Marty. The Rumrunners: A Prohibition Scrapbook. Biblioasis. 1980, Revised & Expanded 2009. ISBN 978-1-897231-62-3.

- Hunt, C. W. Whisky and Ice: The Saga of Ben Kerr, Canada's Most Daring Rumrunner. Dundurn Press. 1995. ISBN 1-55002-249-0.

- Mason, Philip P. Rumrunning and the Roaring Twenties: Prohibition on the Michigan-Ontario Waterway. Wayne State University Press, 1995.

- Miller, Don. I was a rum runner. Lescarbot Printing Ltd. 1979.

- Montague, Art. Canada's Rumrunners: Incredible Adventures and Exploits During Canada's Illicit Liquor Trade. Altitude Publishing Canada. 2004. ISBN 1-55153-947-0.

- Moray, Alastair. The diary of a rum-runner. P. Allan & Co. Ltd. 1929, Reprint in 2006. ISBN 0-9773725-6-1

- Snow, Nicholas. "Law of the Rum-Runners: Self-Enforcement Mechanisms Given Weak Focal Points". Grove City College. October 2007.

- Steinke, Gord. Mobsters & Rumrunners Of Canada: Crossing The Line. Folklore Publishing. 2003. ISBN 978-1-894864-11-4. ISBN 1-894864-11-5.

- Willoughby, Malcolm F. Rum War at Sea. Fredonia Books. 2001. ISBN 1-58963-105-6.

- Mark Thornton, The Economics of Prohibition, Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 1991.

- Yandle, Bruce. Bootleggers and Baptists: The Education of a Regulatory Economist. Regulation 7, no. 3. 1983: 12.

External links

- Data on Alcohol Smuggling: Havocscope Black Markets

- http://www.uscg.mil/history/articles/RumWar.pdf

- http://www.uscg.mil/history/webcutters/Seneca1908.pdf

- http://www.providenceri.com/narragansettbay/rum_runners.html#blackduck

- "Bootleggers and Baptists in Retrospect"

- "Submarine on Wheel is Used as Rum Runner" Popular Mechanics, November 1930

- Rum Runner at A History of Central Florida Podcast

.jpg)