Mapuche conflict

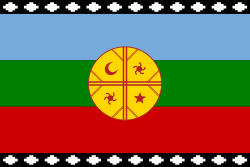

The Mapuche Conflict is the name given to the conflict originated from the claims of indigenist Mapuche communities and organizations to the States of Chile and Argentina. The activist in favor of the 'Mapuche cause' claim greater autonomy, recognition of rights, and the 'recovery' of land since the Chilean transition to democracy.

The Mapuche conflict is a phenomenon mainly from Chile, but also from neighboring areas of Argentina. Demands revolve mainly around three themes: jurisdictional autonomy, return of ancestral lands, and cultural identity. The Mapuche conflict has generated debates that take place in different areas, from the legal discussion through the historiographic controversy about their status as indigenous peoples to the controversial use of the term of terrorist.[1][2][3] Historian Gonzalo Vial claims that a "historical debt" exists towards the Mapuche by the Republic of Chile, whereas the Coordinadora Arauco-Malleco aims at a national liberation of Mapuches.[4][5]

Background

The Mapuche conflict surfaced in the 1990s following the return of democracy.[6] The conflict started in areas inhabited mostly by Mapuches like the vicinities of Purén, where some indigenous communities have been demanding that certain lands they claim for their own but which are now the property of logging and farming companies and individuals be turned over to them.[7] Several Mapuche organizations are demanding the right of self-recognition in their quality of Indigenous peoples, as recognized under the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by the General Assembly of the United Nations.

The official 2002 Chilean census found 609,000 Chileans identifying as Mapuches.[8] The same survey determined that 35 percent of the nation's Mapuches think the biggest issue for the government to resolve relates to their ancestral properties.[8] The official 2012 Chilean census found the number of Mapuches in Chile to be 1,508,722.[9]

Historian José Bengoa has likened the Mapuche conflict to the Catalan struggle. Bengoa adds that both conflicts were major concerns for the 17th century Spanish Empire and remain unresolved.[10]

1990-2009

1996–2004: Ralco controversy

The building of the Ralco Hydroelectric Plant, Chile's largest hydroelectric power plant, in the 1990s was highly controversial among Mapuches and pro-Mapuche groups as it was to flood allegedly sacred land including one Mapuche cemetery. After compensations were paid the plant was finally finished in 2004.[11]

2009 incidents

Numerous incidents such as violent land occupations, burning of private property and demonstrations have occurred in Araucania. In the wake of the recent deaths of a few of its activists, Mapuche organization Coordinadora Arauco-Malleco has played a key role by organizing and supporting violent land occupations and other direct actions, such as burning of houses and farms, that have ended up in clashes with the police. The government of Michelle Bachelet has said that it is not ready to contemplate expropriating land in the southern region of Araucania to restore lost ancestral territory to the Mapuche.[12]

The government set out to buy land for use by 115 Mapuche communities, however, according to government officials, the current owners have nearly tripled the prices they are demanding. On the other hand, the effectiveness of the government policy of buying and distributing land has been questioned.[12] Two special presidential envoys were sent to southern Chile to review the increasingly fractious “Mapuche situation”.[8]

2010–present

2010 hunger strike

Between 2010 and 2011, a series of hunger strikes by Mapuche community members imprisoned in Chilean prisons to protest against the conditions in which the proceedings against them took place, mainly due to the application of the antiterrorist law, and for the double prosecutions they were subject to, because parallel proceedings were carried out in the ordinary and military courts.

The strikes began on July 12, 2010, with a group that was in preventive detention, some for more than one year and a half, all accused of violating anti-terrorism legislation.[13][14]

2012 fires

January 2013 events

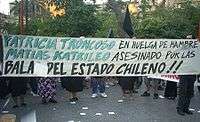

A march was held in commemoration of the death of Matías Catrileo held in Santiago in January 2013. During the march a group of masked men attacked banks and threw molotov cocktails. Later the same group caused incidents near Estación Mapocho.[15] The commemoration was associated by newspaper La Tercera with the assault and torching of a truck in Chile Route 5 in Araucanía Region.[16]

In the morning of January 4, 2013 the agricultural business couple Luchsinger-Mackay died in a fire in their house in Vilcún, Araucanía Region.[17][18] The prosecutor said it was arson in a preliminary report and newspaper La Tercera linked it to the commemoration of the death of Matías Catrileo and to the truck burning the previous days.[19] A relative of the dead persons claimed there was a campaign to empty the region of farmers and businessmen adding that "the guerrilla is winning" and lamented the "lack of rule of law".[19] A male activist wounded by a bullet was detained by police 600 m from the torched house.[18] A thesis claims the house was attacked by at least seven persons and that the "machi" had received the bullet wound from the occupants of the house before dying in the fire.[18]

On April 30 a freight train was derailed near Collipulli to be then assaulted by men with firearms.[20][21] Interior minister Andrés Chadwick said the Chilean Antiterrorist Law will be applied to those responsible for the attack.[20]

2016–2020: Upsurge of the conflict

Since 2016, there has been an increase in attacks in the region, especially against churches, machinery, forest industries, and security forces.[22][23] For their part, "the military police (GOPE) often intervene violently, on the side of the companies, intimidating the Mapuche communities, acting indiscriminately against women or minors."[24] The priest Carlos Bresciani, SJ, who has spent 15 years heading the Jesuit Mapuche Mission in Tirúa,[25] doesn't see autonomy coming easily, given the disposition of the Chilean Senate, but he says "The underlying problem is how communities participate in decision-making in their own territories".[3][26] Bresciani observed that the violence "reflects that there is an open wound."[27] In January 2018, while saying Mass before thousands at Temuco, "the de facto capital of the Mapuche community", Pope Francis called for an end to the violence,[28] and for solidarity with "those who daily bear the burden of those many injustices".[29]

In the course of events, 1 casualty was recorded in 2016[30] and 1 in 2017. On 20 December 2019, the UNO urged Switzerland to stop deportation of Mapuche activist Flor Calfunao to Chile on concerns over her human rights, including the risk of being subjected to torture.[31]

See also

References

- Identidad y conflicto mapuche en los discursos de Longkos y Machis (IX Región - Chile), por Jorge Araya Anabalón

- Conflicto mapuche y propuestas de autonomía mapuche Archived 2000-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, por Javier Lavanchy

- S.A.P., El Mercurio. "Carlos Bresciani, el jefe jesuita en la zona mapuche: "Lo que el Estado no hizo de derecho, las comunidades lo están haciendo de hecho"". LaSegunda.com (in Spanish). Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- Foerster, Rolf 2001. Sociedad mapuche y sociedad chilena: la deuda histórica. Polis, Revista de la Universidad Bolivariana.

- https://www.mapuche-nation.org/espanol/html/documentos/doc-104.htm

- On the conflict before 1990 see Olaf Kaltmeier: Volkseinheit und ethnische Differenz. Mapuche-Bewegung und comunidades während der Regierung Salvador Allende, in:Jahrbuch für Forschungen zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, Heft III/2003 (German Language).

- "Chilean Authorities Investigate New Attack, Land Occupations". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved August 28, 2009.

- "CHILE INDIGENOUS CONFLICT MAKES POLITICAL WAVES". Retrieved August 28, 2009.

- "Censo 2017 – Todos Contamos – Este Censo necesita todo tu apoyo para saber cuántos somos, cómo somos y cómo vivimos". www.censo.cl (in Spanish). Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- Bengoa, José (October 4, 2017). "Columna de José Bengoa: Catalanes, Autonomías y Mapuche (s)". The Clinic (in Spanish). Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- Electricity generation capacity of Chile by Comisión Nacional de Energía

- "Chile Rules Out Land Seizures to Satisfy Indian Demands". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved August 28, 2009.

- "Comuneros mapuche deponen huelga de hambre tras 87 días (In Spanish)". Bio Bio Chile. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- "Ratifican fallo absolutorio de Juzgado Militar en caso de mapuche condenados por ataque a fiscal (In Spanish)". Bio Bio Chile. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- Marcha por conmemoración de muerte de Matías Catrileo provoca incidentes en Santiago Centro, La Tercera, January 3, 2013. Retrieved on April 4, 2013.

- Quema de camión en La Araucanía marca conmemoración de muerte de Matías Catrileo, La Tercera, January 3, 2013. Retrieved on April 4, 2013.

- Fiscalía confirma muerte de dos personas en nuevo atentado incendiario a casa patronal en La Araucanía, La Tercera, January 4, 2013. Retrieved on April 4, 2013.

- Pericias indican que Werner Luchsinger y Vivian MacKay murieron por acción del fuego, El Mercurio, March 23, 2013. Retrieved on April 4, 2013.

- Familia confirma que los fallecidos en ataque a casa patronal en La Araucanía son el matrimonio Luchsinger, La Tercera, January 4, 2013. Retrieved on April 4, 2013.

- Se aplicará la Ley Antiterrorista contra los responsables del atentado en Collipulli, cnn.

- Tren de carga sufrió descarrilamiento en Collipulli, Radio Cooperativa.

- "Al menos 23 camiones incendiados en el Biobío y La Araucanía". Tele 13 (in Spanish). Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- Cooperativa.cl. "Quema de camiones en La Araucanía y Biobío: Gobierno se querella por incendio terrorista". Cooperativa.cl (in Spanish). Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- "In Chile, the Mapuche are battling for their land". Equal Times. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- Jesuitas, Misión Mapuche- (May 28, 2009). "Misión Jesuita Mapuche: Noticias de Mayo..." Misión Jesuita Mapuche. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- "Ñuke Mapu - Centro de Documentación Mapuche". www.mapuche.info. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- Poblete, Kate Linthicum, Jorge. "The long fight of the Mapuche people at times has turned violent. Pope Francis is about to get involved". latimes.com. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- "Pope urges end to Chile Mapuche conflict". BBC News. 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- Staff and agencies in Temuco (January 17, 2018). "Pope wades into indigenous conflict telling Chile's Mapuche to shun violence". the Guardian. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- Chile, C. N. N. "Comité ONU: Suiza debe detener la deportación a Chile de mapuche por riesgo de sufrir tortura". CNN Chile (in Spanish). Retrieved December 20, 2019.